Manor of Hunningham

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Hunningham is a medieval manor located in the West Midlands (region) of Warwickshire, England. Its location is just over three miles northeast of Leamington Spa in Warwickshire. The River Leam – located on Hellidon Hill in Northamptonshire, which then flows through rural Warwickshire, including the town of Leamington Spa – forms the Manor boundary between north and west. The Fosse Way crosses the center of the town diagonally and here is a perfectly paved road. The southeast boundary of Hunningham is formed by the River Itchen, a tributary of the Leam. Today the Manor includes the parish of Hunningham. The history of the Manor of Hunningham is of great interest because it has been documented continuously for a thousand years, from the time of the Domesday Book to the present day. However, it is assumed that the creation of the Manor of Hunningham dates back to the 9th century, but there are currently no documents to prove this.[1]

Descent of the Manor[edit]

The descent of the manor was as follows:

William Fitz Corbucin, 1086[edit]

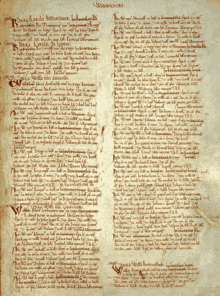

The Domesday Book states that in 1086 the Manor of Hunningham belonged to William Fitz Corbucin, whose tenants were Osmund and Chetel. William Fitz Corbucin was one of William the Conqueror's foremost supporters in Warwickshire, holding several manors in the county, of which he was probably the sheriff.[4]

Robert Corbucin –[edit]

Robertin Corbucin succeeded William Fitz Corbucin, becoming Lord of the Manor of Hunningham.[5]

Geoffrey Corbucin, 1161[edit]

In 1161 Geoffrey Corbucin became Lord of Hunningham, succeeding Robertin Corbucin.[6]

Peter Corbucin of Studley, 1166[edit]

In 1166 Peter Corbucin of Studley became Lord of Hunningham, succeeding Geoffrey Corbucin.[5]

Peter Corbucin, enfeoffed William de Cantilupe, 1200[edit]

In 1200 Peter Corbucin, son of Peter Corbucin of Studley, became Lord of the Manor of Hunningham, giving William de Cantilupe.[7]

Richard Corbucin –[edit]

After Peter Corbucin, Richard Corbucin became Lord of the Manor of Hunningham, who died in 1227.[8]

Geoffrey Corbucin, 1227[edit]

In 1227 Geoffrey Corbucin became Lord of the Manor of Hunningham, brother of Peter Corbucin.[9]

Richard Corbucin –[edit]

After Geoffrey Corbucin, his brother Richard Corbucin became Lord of the Manor of Hunningham.[9]

John Hastings, 1st Baron Hastings, Lord Abergavenny, 1284[edit]

In 1284, John Hastings, 1st Baron Hastings was Lord of the Manor of Hunningham, he was feudal lord of Abergavenny. John Hastings was an English peer and soldier. He was one of the contenders for the Crown of Scotland in 1290-92 in the Great Cause. He was born in 1262 in Allesley, near Coventry in Warwickshire. In 1273, he became the thirteenth lord of Abergavenny upon the death of his childless uncle Sir George de Cantilupe, thus acquiring Abergavenny Castle and the vast lands of honor of Abergavenny. He has also inherited many Cantilupe estates including Aston Cantlow in Warwickshire, one of that family's headquarters. He fought from 1290 in the Scottish, Irish and French wars of King Edward I of England and simultaneously held the offices of seneschal of Gascony and lieutenant of Aquitaine.

In 1290, he had unsuccessfully contested the crown of the Kingdom of Scotland as the grandson of Ada, the third daughter of David of Scotland, Earl of Huntingdon, grandson of King David I of Scotland. Also in 1290 he was summoned to the English Parliament as Lord Hastings, who created him an equal. In February 1300-1 he was licensed to battlements his manor and the town of Fillongley in Warwickshire. He signed and sealed the Letter of the Barons of 1301 to Pope Boniface VIII, to protest against papal interference in Scottish affairs.[10]

John Hastings, 2nd Baron Hastings, 1325[edit]

In 1325 John Hastings, 2nd Baron Hastings, son John Hastings, 1st Baron Hastings, became Lord of the Manor of Hunningham. He served in the First War of Scottish Independence under Edward II of England and was also governor of Kenilworth Castle.[11]

William Trussell, 1334[edit]

In 1334 William Trussell became Lord of the Manor of Hunningham. He was the son of Sir William Trussell, an English politician and rebel leader in Queen Isabella and Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March's rebellion against Edward II.[12]

Isabell wife of Walter son of Hugh de Cokesey, 1353[edit]

In 1353 Isabel wife of Walter de Cokesey, owned the lordship of the Manor of Hunningham.[13]

– Sir Hugh de Cokesey, dsp 1445[edit]

When Walter de Cokesey and his wife Isabel died, their son Sir Hugh de Cokesey became Lord of the Manor of Hunningham.[14]

Alice de Cokesey, 1445[edit]

In 1445 Alice de Cokesey inherited the lordship of Hunningham from her husband Sir Hugh de Cokesey, when he died.[15]

Joyce Beauchamp, 1460[edit]

Alice de Cokesey died in 1460, the lordship of the Manor of Hunningham was thus inherited by her sister, Joyce Beauchamp, who died in 1473.[16]

Sir John Greville, 1473[edit]

In 1473 Sir John Greville (died 1480) became Lord of the Manor of Hunningham, when Joyce Beauchamp died. Sir John Greville was an English nobleman of the Greville family. His father John Greville (died 1444) served as a Member of Parliament in seven English parliaments.[17]

Sir Thomas Cokesey, 1480[edit]

Sir John Greville died in 1480 and was succeeded by his son Thomas, who changed his name to Cokesey, and became Sir Thomas Cokesey, Lord of the Manor of Hunningham.[18]

John Underhill, 1500[edit]

John Underhill in 1500 acquired the lordship of the Manor of Hunningham.[19]

Thomas Underhill, 1518[edit]

In 1518 Thomas Underhill, son of John Underhill, became Lord of the Manor of Hunningham.[20]

Edward Underhill –[edit]

After Thomas Underhill, Edward Underhill became Lord of the Manor of Hunningham, grandson of John Underhill.[21]

Richard Newport, 1545[edit]

In 1545 Richard Newport bought the lordship of Hunningham from Edward Underhill.[20]

John Newport, 1565[edit]

In 1565 John Newport, son of Richard Newport, became Lord of the Manor of Hunningham.[22]

William Newport, later called Sir William Hatton, 1566[edit]

In 1566 William Newport, upon the death of his father John Newport, became Lord of the Manor of Hunningham. Since he inherited Hatton's estates through his mother, he had to adopt the surname Hatton for himself.[23]

Frances Hatton and husband Sir Robert Rich, 1596[edit]

In 1596 Frances Hatton owns the lordship of Hunningham.[24] In 1605 she married Robert Rich, 2nd Earl of Warwick, was an English colonial administrator, admiral, and Puritan, who commanded the Parliamentarian navy during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Robert Rich, later Lord Holland, was the eldest son and third of four children born to Robert Rich, 1st Earl of Warwick (1559-1619) and his first wife Penelope (1563-1607). He had two sisters, Essex (1585-1658) and Lettice (1587-1619) and a younger brother Henry Rich, 1st Earl of Holland (1590–1649). He succeeded to his father's title as Earl of Warwick in 1619. Early developing interest in colonial ventures, he joined the Guinea, New England, and Virginia companies, as well as the Virginia Company's offspring, the Somers Isles Company. Warwick's enterprises involved him in disputes with the British East India Company (1617) and with the Virginia Company, which in 1624 was suppressed as a result of his action. In August 1619, one of the privateer ships sponsored by the Earl, the White Lion, delivered the first enslaved Africans to colonial Virginia. The ship, flying a Dutch flag, landed at what is now Hampton, Virginia with approximately 20 African captives from the present-day Angola. They had been taken by the privateers from a Portuguese slave ship, the São João Bautista.[25][26] In 1627 he commanded an unsuccessful privateering expedition against the Spanish.[27] He sat as a Member of Parliament for Maldon for 1604 to 1611 and for Essex in the short-lived Addled Parliament of 1614.[28]

Thomas Gibbes, 1611[edit]

In 1611 Thomas Gibbes became Lord of the Manor of Hunningham.[28]

John Woodward –[edit]

During the early part of the seventeenth century, the lordship of Hunningham passed from Thomas Gibbes to John Woodward.[29]

Timothy Wagstaff, 1614[edit]

In 1614 Timothy Wagstaff was Lord of the Manor of Hunningham.[29]

Hannibal Horsey, 1614[edit]

In 1614 after Timothy Wagstaff Lord of the Manor of Hunningham became Hannibal Horsey.[30]

James Horsey, 1622[edit]

In 1622 James Horsey became Lord of the Manor of Hunningham after the death of Hannibal Horsey.[31]

Dorothy Horsey, wife of George Fane, 1630[edit]

James Horsey died in 1630, left no child behind and the lordship of the Manor of Hunningham then passed to his daughter Dorothy Horsey, wife of George Fane.[31]

Colonel George Fane, 1653[edit]

In 1653 Colonel the Hon. George Fane married Dorothy Horsey and became Lord of the Manor of Hunningham, as evidenced by the interesting manuscripts of Stoneleigh Abbey at the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust registration office in Stratford on Avon. George Fane was the fifth but fourth surviving son of Francis Fane, 1st Earl of Westmorland and his wife, Mary Mildmay (died 1640), daughter and heir of Sir Anthony Mildmay of Apethorpe, Northamptonshire. He was educated at Eton College from 1637 to 1632)[32] and matriculated from Emmanuel College, Cambridge in 1632.[33] He travelled abroad from 1635 to 1638, visiting Italy. In 1640, Fane was elected Member of Parliament (MP) for Callington in Cornwall, a seat controlled by the Rolle family of Heanton Satchville, Petrockstowe. By 1642, he was a Captain of an Irish foot regiment and was Royalist lieutenant colonel by 1643. He was colonel of a foot regiment from 1644 to 1649 and fought as a colonel at Marston Moor. Fane acquired the mortgage, in trust for his son, of a Thameside Berkshire estate at Basildon House in 1656 in the names of his sister, Rachael Fane (styled Lady Bath) (who may have supplied the money) and his nephew, Charles Fane, Lord le Despenser (later the third Earl of Westmorland and 10th Baron le Despencer). Following the Restoration he was a Justice of the Peace and a Deputy Lieutenant for Berkshire until his death. He was a Commissioner for assessment for Warwickshire from August 1660 to 1661 and one for Berkshire from 1661 to 1663. In 1661 Fane was elected MP for Wallingford in the Cavalier Parliament. He was one of the most active Members in the opening sessions of the parliament, serving on 84 committees.[34]

Sir Henry Fane of Bassledon, Berks, –[edit]

George Fane left the lordship of the Manor of Hunningham to his son Sir Henry Fane of Bassledon, Berkshire.[35]

Thomas and George Watson, 1692[edit]

In 1692 Thomas Watson of Tidmington co. Worcester and George Watson bought the lordship of Hunningham.[35]

Thomas Leigh, 2nd Baron Leigh, 1695[edit]

In 1695 Thomas Leigh, 2nd Baron Leigh, bought the lordship of Manor of Hunningham. With this change of ownership in 1695, a very important period in the history of the Manor began. The Manor has in fact remained the property of the Baron Leigh for almost 300 years, this long period has helped to strengthen and preserve the Manor, especially as regards its historical identity.[36]

Edward Leigh, 3rd Baron Leigh, 1710[edit]

Edward Leigh, aged 25, became the 3rd Baron Leigh and Lord of the Manor of Hunningham after his father's death in 1710. He followed in the footsteps of his father politically and in 1705 he married Mary Paulet. Edward and his wife had two children, the eldest of whom died at the age of 18 in 1737, just a few months before his father.[1]

Thomas Leigh, 4th Baron Leigh, 1738[edit]

In 1738, on the death of Edward Leigh, the title and estates, including the lordship of Hunningham, were inherited by the younger son Thomas, 4th Baron Leigh. The 4th Baron was born in 1713 and in 1736 he married Maria Craven, with whom he had four children, however Lady Leigh died in 1746. In 1747 Thomas Leigh remarried, this time to Catherine Berkeley, but died shortly thereafter at the age of 36 years, without having other children.[1]

Edward Leigh, 5th Baron Leigh, 1749[edit]

Edward Leigh, 5th Baron Leigh was the only surviving son of Thomas Leigh, 4th Baron Leigh and Lord of the Manor of Hunningham. He inherited his father's properties and titles when he was only 7 years old in 1749. He never married and was declared insane in 1774. He died in 1786 and as he had no children the title of Baron Leigh died out.[37]

Mary Leigh, 1786[edit]

By the will of Edward Leigh, 5th Baron Leigh and Lord of the Manor of Hunningham, the estates went to his sisters, together, and their children, among the sisters was the Hon. Mary Leigh, who in 1786 became Lady of Hunningham.[37]

Rev Thomas Leigh, 1806[edit]

From 1806 Rev Thomas Leigh became Lord of the Manor of Hunningham, after the death of the Hon. Mary Leigh.[37]

James Henry Leigh of Adelstrop, 1813[edit]

In 1813 James Henry Leigh of Adlestrop became Lord of the Manor of Hunningham.[37]

Chandos Leigh 1st Baron Leigh, died 1850[edit]

When James Henry Leigh of Adlestrop died in 1823, his estates passed to his son Chandos Leigh, 1st Baron Leigh, including the lordship of Hunningham. Chandos Leigh in 1839 was created Lord Leigh of Stoneleigh by the liberal government of the time: he was the first baron of the new creation. He was very interested in the politics and social issues of the time and took part in debates in the House of Lords, where he could put some of his ideas into practice. However, although he had shown an interest in liberal politics, he was rarely in the House of Lords but preferred to remain in Warwickshire, where he was a magistrate. In 1819 he married Margarette Willes, daughter of a priest. The spouses had the typical large Victorian family, with ten sons, three sons and 7 daughters.[38]

William Henry Leigh, 2nd Baron Leigh, 1850[edit]

William Henry Leigh, 2nd Baron Leigh in 1850, when his father died of apoplexy and paralysis, became Lord of the Manor of Hunningham. This Baron Leigh, along with his younger brother Edward, inherited his father's interest in politics. Edward was an adviser to the Speaker of the House of Commons from 1883 to 1907 and William ran as a Liberal candidate for North Warwickshire in 1847. William Leigh, 2nd Baron Leigh and Lord of Hunningham, was Lord Lieutenant of Warwickshire from 1856 until his death and was also appointed colonel in the 3rd Battalion of the local regiment, the Warwickshire Regiment. He was High Superintendent of Sutton Coldfield from 1859 until 1892, when the government ended after a new statute was issued for the district, but was reappointed in September 1902. He also held the position of Justice of the Peace for Gloucestershire. He donated the land for the construction of St Alban's Church, Holborn, in central London.[39]

Francis Leigh, 3rd Baron Leigh, 1905[edit]

In 1905 Francis Leigh, 3rd Baron Leigh, became Lord of Hunningham. Francis Leigh married twice, with American women, but had no children. He died in May 1938.[1]

Rupert William Leigh, 4th Baron Leigh, 1938[edit]

In 1938 Rupert William Dudley became 4th Lord Leigh and Lord of the Manor of Hunningham. Rupert William Dudley was the grandson of Francis Dudley Leigh, the eldest son of his brother Rupert.[1]

John Piers Leigh, 5th Baron Leigh, 1979[edit]

In 1979 John Piers Leigh, the 5th Baron Leigh, became Lord of the Manor of Hunningham.[1]

Roy Chew, Hunningham, 1989[edit]

In 1989, the lordship of the Manor of Hunningham was sold by John Piers Leigh, 5th Baron Leigh, to Roy Chew of Hill House in Hunningham. After 300 years, it ceased to be owned by the Leigh Barons.[40][41]

Dr Luca Lombardi, Bari, Italy, 2020[edit]

In 2020 the Lordship of the Manor of Hunningham was transferred to Dr. Luca Lombardi of Bari, Italy, who is the current Lord of Hunningham and holder of all rights associated with it. Dr. Luca Lombardi is a historical and numismatic researcher, editor, is a life member of The Manorial Society of Great Britain, founded in 1906, is a member of Historical Families of Europe, founded in 2011, of the Italian Genealogical Heraldic Institute, founded in 1993.[40][41]

St Margaret Church[edit]

Historic buildings in Hunningham include the medieval church of St Margaret, located on the east bank of the River Itchen, north of the Manor of Hunningham. It is a church consisting of a choir, central nave, north nave, sacristy, south portico and a wooden bell on the west tympanum. It dates back to the last part of the thirteenth century, when it consisted of a nave and a presbytery, and appears to have been repaired at the end of the fourteenth century and rebuilt at the end of the sixteenth century; in modern times a north corridor, a sacristy and a south portico were added. All roofs are covered with tiles. The presbytery, with the exception of the parts of the north and south walls adjacent to the nave, was completely redone with a light-colored sandstone ashlar, while the old portions were of red sandstone that flowed among the rubble. The end is leaning against the angular buttresses and is illuminated by a simple openwork window with two pointed arched lights. On the southwestern outer side there is a rectangular window on the lower side of two diverging orders, and a modern central buttress that divides the ancient walls from the modern ones. The south wall of the nave has three windows with two trefoil lights with holes under the square heads, all modern but perhaps copies of the pre-existing 14th century windows. Between the last two there is a four-pointed door, with a single opening, covered by a modern wooden porch. The west tympanum of the nave is the most interesting and unaltered part and is built with rubble of red sandstone with ashlar coverings. In the center is a buttress-like protuberance showing the apex of the eardrum, where it is exposed to the elements. Contains a long blunt hand with simple label printing. On the top of the tympanum there is a small square bell with a bell-shaped edge for two bells, with a pyramidal roof ending with a weather vane depicting a rooster. Observation following the removal of two sections of pews and raised flooring on the south half of the nave revealed load-bearing dwarf brick walls. The joists of the eastern section were oak, original and probably contemporary to the late 19th century, black and red tiled passages between the pews. Those in the western section were softwood, suggesting that this section had been replaced earlier. The depth of the voids under the bench floors suggested that the original solid floor levels had been excavated to a depth of 0.4m. when the tile passages and benches were placed.[42]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f "Hunningham", in A History of the County of Warwick: Vol. VI, pp. 118.

- ^ Cokayne, The Complete Peerage, new edition, vol.VI, p.347

- ^ Per the Collins Roll; the Dering Roll, A217; The Caerlaverock Poem, K83; St George's Roll, E119 & The Galloway Roll, GA223 [1]

- ^ VCH Warw. VI, 333.

- ^ a b Dugd. 741.

- ^ Add. Chart. 48165.

- ^ V.C.H. Warw. iii, 181.

- ^ Roll of Justices in Eyre in Warws. (Selden Soc.), 669.

- ^ a b Feet of F. (Dugd. Soc. xi), 379, 407.

- ^ Plac. de Quo War. (Rec. Com.), p. 777.

- ^ Cal. Inq. p.m. vi, 612.

- ^ Feet of F. (Dugd. Soc. xv), 1765.

- ^ Cal. Inq. p.m. x, 329.

- ^ Chan. Inq. p.m. 24 Hen. VI, no. 36.

- ^ Cal. Fine R. xix, 279.

- ^ Chan. Inq. 38–39 Hen. VI, no. 49.

- ^ Chan. Inq. p.m. 13 Edw. IV, no. 32.

- ^ Early Chan. Proc. 886, no. 15; 892, no. 21; 893, 16.

- ^ Feet of F. (Dugd. Soc. xviii), 2772; Chan. Inq. p.m. (Ser. 2), xxxv, 70.

- ^ a b Feet of F. Warw. East. 36 Hen. VIII.

- ^ Feet of F. Warw. Trin. 2 Edw. VI.

- ^ Chan. Inq. p.m. (Ser. 2) cxliii, 3.

- ^ Baker, Northants. 197.

- ^ Hunningham, in A History of the County of Warwick: Vol. 6, Knightlow Hundred, ed. L F Salzman (London, 1951), pp. 117-120.

- ^ [2][dead link] 400 years ago, enslaved Africans first arrived in Virginia

- ^ https://time.com/5653369/august-1619-jamestown-history/, The First Africans in Virginia Landed in 1619. It Was a Turning Point for Slavery in American History—But Not the Beginning

- ^ This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Warwick, Sir Robert Rich, 2nd Earl of". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 349.

- ^ a b "RICH, Sir Robert (c.1588–1658), of Wallington, Norf., Hackney, Mdx. and Allington House, Holborn, Mdx.; later of Leez Priory, Essex". History of Parliament Trust. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ a b Feet of Warw. Mich. 12 Jas. I.

- ^ Chan. Inq. pm (Ser.2), cccc, 82.

- ^ a b Chan. Inq. pm (Ser.2), cccclvii, 129.

- ^ History of Parliament Online - Fane, George

- ^ "Fane, George (FN632G)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ Recov. R. Trin. 1653, ro. 144.

- ^ a b Feet of F. Warw. Trin. 2 Wm. & Mary.

- ^ Dugd. 360.

- ^ a b c d For his connexion with the then extinct Leigh barony see G. E. C., Compl. Peerage, 2nd ed. vii, 570. His son Chandos was 1st baron of the second creation.

- ^ White, Directory Warws. 686.

- ^ Kelly, Directory Warws.

- ^ a b Historical archive of the Manorial Society of Great Britain

- ^ a b "The Manor of Hunningham: A History Going Back a Thousand Years".

- ^ "Hunningham", in A History of the County of Warwick: Vol. VI, pp. 119.

Bibliography[edit]

- Hunningham, in A History of the County of Warwick: Vol. 6, Knightlow Hundred, ed. L F Salzman (London, 1951), pp. 117–120.

- Cokayne, The Complete Peerage, The complete peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United kingdom, extant, extinct or dormant, A. Sutton, Gloucester, 1982.

- Barlichway Hundred, The Victoria history of the county of Warwick, vol. III, Institute of Historical Research, London 1945.

- Pugh, The Victoria history of the county of Warwick, vol. VI, Institute of Historical Research, London 1951.

- Stephens, The Victoria history of the county of Warwick, vol. VIII, Institute of Historical Research, London 1969.

Further reading[edit]

- Bloch, Marc, Feudal Society Tr. L.A. Manyon. Two volumes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1961. ISBN 0-226-05979-0

- Guerreau, Alain, L'avenir d'un passé incertain Paris: Le Seuil 2001. (Complete history of the meaning of the term.)

- Poly, Jean-Pierre and Bournazel, Eric, The Feudal Transformation, 900–1200., Tr. Caroline Higgitt. New York and London: Holmes and Meier 1991.

- Reynolds, Susan, Fiefs and Vassals: The Medieval Evidence Reinterpreted. Oxford: Oxford University Press 1994. ISBN 0-19-820648-8

External links[edit]

- The Manor of Hunningham

- Commercial Site selling Domesday Book on The National Archives website, home of Domesday Book.

- Online Edition of Domesday Book, housed on The National Archive website. Searchable; downloads are charged.

- Searchable index of landholders in 1066 and 1087, Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England (PASE) project.

- Warwickshire County Council

- Warwickshire College Homepage

This article needs additional or more specific categories. (December 2020) |