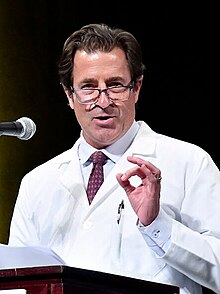

Mark T. Gladwin

Mark T. Gladwin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Alma mater | University of Miami |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Heart and vascular medicine |

| Institutions | National Institutes of Health University of Pittsburgh University of Maryland, Baltimore |

| Website | University of Maryland School of Medicine Office of the Dean |

Mark T. Gladwin is an American physician-scientist and academic administrator serving as the dean of the University of Maryland School of Medicine since 2022. He is also the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and vice president for medical affairs of the University of Maryland, Baltimore.[1][2]

Education and career[edit]

Gladwin earned a B.S. and M.D. (1991) from the University of Miami.[3] He completed an internal medicine internship and residency in 1994 and served as chief resident in 1995 at the Oregon Health & Science University.[3] He was a critical care fellow at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in 1996.[3] In 1998, he completed a fellowship in pulmonary critical care at the University of Washington.[3] He returned to the NIH Clinical Center as a senior research fellow in critical care medicine until 2000, also serving as the Chief of the Pulmonary and Vascular Medicine Branch of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.[4][3]

Gladwin joined the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine in 2008 as a professor and the inaugural director of the University’s Vascular Medicine Institute.[5] In 2015, he was appointed chair of the department of medicine. By the time Gladwin left the university in 2022, the department employed more than 1,000 faculty and had combined clinical and research revenues of almost $600 million.[6][7]

On August 1, 2022, Gladwin was appointed dean of the University of Maryland School of Medicine,[3] succeeding longtime dean E. Albert Reece.[5] He oversees 46 academic departments with a total annual operating budget of $1.3 billion and more than 7,000 faculty, trainees, students and staff.[8]

Gladwin is co-author of two medical textbooks in the "Made Ridiculously Simple" series from publisher Medmaster Inc. He wrote Clinical Microbiology Made Ridiculously Simple with physicians William Trattler and C. Scott Mahan, and Critical Care and Hospitalist Medicine Made Ridiculously Simple with physician Michael Donahoe.[9][10]

Research[edit]

Gladwin is a vascular, heart, and lung physician-scientist who has specialized in the study of reactive nitrogen molecules, like nitric oxide and nitrite, and how they regulate blood flow via reactions with hemoglobin. Researchers in the late 1970s[11] discovered that nitric oxide (NO) regulated blood flow by triggering vasodilation, the widening of blood vessels. However, scientists considered metabolites of NO, such as nitrite (NO2), to be inert.[12] But in 2003, Gladwin and a team of researchers published a paper in Nature Medicine demonstrating that nitrite could also trigger vasodilation, through conversion to NO, under low oxygen conditions in the body such as during a heart attack or stroke.[13] Subsequent studies by other researchers suggest nitrite administered before or immediately following a heart attack could help preserve heart tissue.[14]

Gladwin has also conducted research on hemoglobin-related proteins, such as neuroglobin, and their possible application as antidotes to carbon monoxide poisoning.[15][16][17] He currently serves as Chair of the Board of Directors of Globin Solutions, Inc., a pre-clinical stage biopharmaceutical company researching rapidly acting antidotes for carbon monoxide poisoning, including a modified form of neuroglobin.[18][19] In December 2023, Gladwin and his team of researchers published a study in Nature Communications on the discovery of the first-ever link between hemoglobin-like protein and normal cardiac development.[20]

Gladwin's work on blood flow and hemoglobin also led to discoveries related to sickle cell disease. In 2004, Gladwin and his colleagues found that 10% of sickle cell patients also exhibited pulmonary hypertension, high blood pressure in the blood vessels that supply the lung, and determined that hypertension was a major cause of death among sickle cell patients. They described this new human disease syndrome, called hemolysis-associated pulmonary hypertension, in the New England Journal of Medicine.[21]

In June 2020, Gladwin initiated a 22-site Phase II clinical trial in France, Brazil, and the U.S. that is exploring whether blood transfusions that use the patient's own blood can improve outcomes and extend survival in patients with sickle cell disease.[22][23]

Personal life[edit]

Dr. Gladwin was born in Palo Alto, California, and was raised in various locations in the U.S. as well as in remote locations in Ghana, Guatemala, and Mexico. His parents, Hugh Gladwin, Ph.D., a professor of anthropology at Florida International University, and Christina Gladwin, Ph.D., a professor of food and resource economics at the University of Florida, studied in these locations.

He is married to Dr. Tammy Shields, an epidemiologist and scientific investigator who has published research on cancer epidemiology and prevention. They have three children. Dr. Gladwin is an avid soccer and fitness enthusiast, currently playing competitive soccer in an over-40 outdoor premier league.

References[edit]

- ^ Baltimore, University of Maryland. "Mark T. Gladwin, MD". University of Maryland, Baltimore. Retrieved 2024-01-12.

- ^ Staff, Daily Record (2022-04-20). "Next dean, VP of medical affairs for UM School of Medicine selected". Maryland Daily Record. Retrieved 2024-01-12.

- ^ a b c d e f "Gladwin, Mark | University of Maryland School of Medicine". www.medschool.umaryland.edu. Retrieved 2023-12-26.

- ^ "Vascular Medicine Branch, Division of Intramural Research, NHLBI, NIH". dir.nhlbi.nih.gov. Retrieved 2024-01-12.

- ^ a b Cohn, Meredith (2022-04-20). "University of Maryland School of Medicine names Pittsburgh medical professor as new dean". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2023-12-26.

- ^ "Gladwin Named Department of Medicine Chair at Pitt School of Medicine". UPMC | Life Changing Medicine. Retrieved 2024-02-15.

- ^ "Request Rejected". dom.pitt.edu. Retrieved 2024-02-15.

- ^ Staff, Daily Record (2022-10-18). "FEATURED MOVER | Dr. Mark Gladwin, UMD School of Medicine". Maryland Daily Record. Retrieved 2024-02-15.

- ^ "Clinical Microbiology Made Ridiculously Simple". MedMaster. Retrieved 2024-03-15.

- ^ "Critical Care and Hospitalist Medicine Made Ridiculously Simple". MedMaster. Retrieved 2024-03-15.

- ^ Ignarro, Louis J. (2000), Kadowitz, Philip J.; McNamara, Dennis B. (eds.), "Nitric Oxide in the Regulation of Blood Flow: A Historical Overview", Nitric Oxide and the Regulation of the Peripheral Circulation, Nitric Oxide in Biology and Medicine, Boston, MA: Birkhäuser, pp. 1–12, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-1326-0_1, ISBN 978-1-4612-1326-0, retrieved 2024-01-12

- ^ Wink, David A. (December 2003). "Ion implicated in blood pact". Nature Medicine. 9 (12): 1460–1461. doi:10.1038/nm1203-1460. ISSN 1546-170X. PMID 14647519. S2CID 29815156.

- ^ Cosby, Kenyatta; Partovi, Kristine S.; Crawford, Jack H.; Patel, Rakesh P.; Reiter, Christopher D.; Martyr, Sabrina; Yang, Benjamin K.; Waclawiw, Myron A.; Zalos, Gloria; Xu, Xiuli; Huang, Kris T.; Shields, Howard; Kim-Shapiro, Daniel B.; Schechter, Alan N.; Cannon, Richard O. (December 2003). "Nitrite reduction to nitric oxide by deoxyhemoglobin vasodilates the human circulation". Nature Medicine. 9 (12): 1498–1505. doi:10.1038/nm954. ISSN 1546-170X. PMID 14595407. S2CID 6370323.

- ^ Griffiths, Kayleigh; Lee, Jordan J.; Frenneaux, Michael P.; Feelisch, Martin; Madhani, Melanie (2021-07-01). "Nitrite and myocardial ischaemia reperfusion injury. Where are we now?". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 223: 107819. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107819. ISSN 0163-7258. PMID 33600852. S2CID 231963701.

- ^ Azarov, Ivan; Wang, Ling; Rose, Jason J.; Xu, Qinzi; Huang, Xueyin N.; Belanger, Andrea; Wang, Ying; Guo, Lanping; Liu, Chen; Ucer, Kamil B.; McTiernan, Charles F.; O’Donnell, Christopher P.; Shiva, Sruti; Tejero, Jesús; Kim-Shapiro, Daniel B. (2016-12-07). "Five-coordinate H64Q neuroglobin as a ligand-trap antidote for carbon monoxide poisoning". Science Translational Medicine. 8 (368): 368ra173. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aah6571. ISSN 1946-6234. PMC 5206801. PMID 27928027.

- ^ Rose, Jason J.; Bocian, Kaitlin A.; Xu, Qinzi; Wang, Ling; DeMartino, Anthony W.; Chen, Xiukai; Corey, Catherine G.; Guimarães, Danielle A.; Azarov, Ivan; Huang, Xueyin N.; Tong, Qin; Guo, Lanping; Nouraie, Mehdi; McTiernan, Charles F.; O'Donnell, Christopher P. (2020-05-08). "A neuroglobin-based high-affinity ligand trap reverses carbon monoxide-induced mitochondrial poisoning". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 295 (19): 6357–6371. doi:10.1074/jbc.RA119.010593. ISSN 1083-351X. PMC 7212636. PMID 32205448.

- ^ Rose, Jason J.; Wang, Ling; Xu, Qinzi; McTiernan, Charles F.; Shiva, Sruti; Tejero, Jesus; Gladwin, Mark T. (2017-03-01). "Carbon Monoxide Poisoning: Pathogenesis, Management, and Future Directions of Therapy". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 195 (5): 596–606. doi:10.1164/rccm.201606-1275CI. ISSN 1535-4970. PMC 5363978. PMID 27753502.

- ^ "Our Team | Globin Solutions, Inc". Retrieved 2024-01-12.

- ^ "Technology | Globin Solutions, Inc". Retrieved 2024-01-12.

- ^ Rochon, Elizabeth R.; Xue, Jianmin; Mohammed, Manush Sayd; Smith, Caroline; Hay-Schmidt, Anders; DeMartino, Anthony W.; Clark, Adam; Xu, Qinzi; Lo, Cecilia W.; Tsang, Michael; Tejero, Jesus; Gladwin, Mark T.; Corti, Paola (14 December 2023). "Cytoglobin regulates NO-dependent cilia motility and organ laterality during development". Nature Communications. 14 (8333): 8333. Bibcode:2023NatCo..14.8333R. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-43544-0. PMC 10721929. PMID 38097556.

- ^ Gladwin, Mark T.; Sachdev, Vandana; Jison, Maria L.; Shizukuda, Yukitaka; Plehn, Jonathan F.; Minter, Karin; Brown, Bernice; Coles, Wynona A.; Nichols, James S.; Ernst, Inez; Hunter, Lori A.; Blackwelder, William C.; Schechter, Alan N.; Rodgers, Griffin P.; Castro, Oswaldo (2004-02-26). "Pulmonary Hypertension as a Risk Factor for Death in Patients with Sickle Cell Disease". New England Journal of Medicine. 350 (9): 886–895. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa035477. ISSN 0028-4793.

- ^ "Sickle Cell Disease and CardiovAscular Risk - Red Cell Exchange Trial (SCD-CARRE) (SCD-CARRE)". ClinicalTrials.gov. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ Cohn, Sarah True,Meredith (2024-01-12). "Maryland doctors are loosening sickle cell's painful grip on patients worldwide". The Baltimore Banner. Retrieved 2024-01-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)