Medical–industrial complex

The medical–industrial complex (MIC) refers to a network of interactions between pharmaceutical corporations, health care personnel, and medical conglomerates to supply health care-related products and services for a profit.[1][2] The term is derived from the idea of the military–industrial complex.[3]

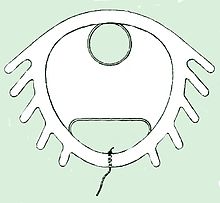

Following the MIC's conception in 1970, the term has undergone an evolution by critical theory scholars throughout the early 21st century—including but not limited to the fields of disability studies, Black studies, feminism, and queer studies—to describe forces of oppression against marginalized communities as they exist in the healthcare field.[4][5][6][7] Mia Mingus, a writer, educator, and disability justice advocate, is one of such notable scholars who created a visual of the MIC.[5] Prior to the conception of the "medical-industrial complex" term, themes related to the MIC were discussed in earlier American society, as shown through the work and philosophies of Rana A. Hogarth and Francis Galton.[8][9]

The medical–industrial complex is often discussed in the context of conflict of interest in the health care industry and is often regarded as a result of modernized healthcare and capitalism.[10] Discussions regarding the medical-industrial complex often include the United States healthcare system.[3] These discussions about the MIC propose that pharmaceutical and healthcare companies, including for-profit chain hospitals, may influence physicians through financial incentives.[11][1] Physicians may also face constraints from corporate regulations and potential conflicts of interest related to investments in medical device companies.[12][13][14] Although some large medical journals have been criticized for potentially biased publications, efforts have been made to maintain neutrality in medical literature.[15][1] Continuing medical education programs funded by pharmaceutical companies may also influence physician preferences.[16] Finally, patients may be affected by the MIC through the promotion of cosmetic surgery, drug price inflation, and physician bias.[11][1] The Food and Drug Administration has implemented laws to protect patients against the potential negative impacts of the medical-industrial complex in the United States.[17][18] These perspectives on the medical-industrial complex also apply to countries outside the United States, such as India and Brazil.[19][20][21][22]

Drawing from diverse theoretical frameworks and the collective efforts of historically marginalized communities, critics have proposed alternatives to the medical-industrial complex that aim to reimagine health as a holistic concept, challenge the medicalization of sickness, and integrate lived experiences into healthcare settings.[23][8][24][25][26][27][28][29]

Origin[edit]

In 1961, President Dwight D. Eisenhower commented on the influence and immensity of the military in American society in his farewell address, “...we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex.”[30] This new term, the military-industrial complex, depicts a sphere of influence between a national military and the defense industry which provides essential supplies to the military.[31] Deriving from this, the compound term composed of the intended institution with “industrial complex” is created to describe the conflict of interest between an institution's supposed goal, and the desire to profit from the businesses/agencies that profit from serving the institution. The conceptual framework of the medical-industrial complex sits alongside the military-industrial complex and the prison-industrial complex, among others, to delineate the influence of free market capitalism in sociopolitical systems/institutions.

The concept of a "medical–industrial complex" was first advanced by Barbara and John Ehrenreich in the November 1969 issue of the Bulletin of the Health Policy Advisory Center in an article entitled "The Medical Industrial Complex" and in a subsequent book (with Health-PAC), The American Health Empire: Power, Profits, and Politics (Random House, 1970).[32] In “The Medical Industrial Complex,” the emergence of the American medical industrial complex is attributed to “the growing rapport between the delivery and products industry.”[32] This definition of the medical-industrial complex describes the history of the American healthcare system, specifically the creation of social programs Medicare and Medicaid, as an industry that has transformed into a central, essential role of the American national economy. References to the perpetuation of healthcare disparities by the medical-industrial complex are described, such as “class and cultural antagonisms.”[32] Differences in accessibility of healthcare between rural and urban populations are also made at this time.[32]

In 1980, Dr. Arnold S. Relman published a further discussion of the medical-industrial complex in The New England Journal of Medicine when he was editor-in-chief, entitled “The New Medical-Industrial Complex.”[33] Relman notably explicitly excludes pharmaceutical companies and medical equipment companies in his description of the medical-industrial complex. Relman argues that “in a capitalistic society there are no practical alternatives to the private manufacture of drugs and medical equipment.”[33] Relman still identifies the novelty of the modern medical-industrial complex, describing the medical-industrial complex as an “unprecedented phenomenon with broad and potentially troubling implications.”[33] As with the Ehrenreich definition, the medical-industrial complex continues an emphasis on profit maximization on behalf of private corporations. The “cream-skimming” phenomenon is described, where proprietary hospitals can “skim the cream” off the market, by focusing on wealthy patients who can afford the most profitable procedures and services; nonprofit hospitals are therefore left with the remaining patient base.[34]

In the 21st century, the medical industrial complex has come to encompass a system of oppression and subject of critical analysis by scholars, activists, organizers, and advocates. The Health Justice Commons describes the medical-industrial complex as intertwined institutions, including big pharma, as well as health insurance companies, medical technology companies, and governmental regulatory bodies.[35] Per the Health Justice Commons, the medical-industrial complex reinforces “racism, sexism, classism, homophobia, transphobia and ableism."[35] The nature and extent of the medical-industrial complex is a subject of debate by scholars, including those who specialize in fields of critical theory, such as disability studies, queer theory, and Black studies. One such contributor is Mia Mingus, a writer and educator, who has attempted to visualize the medical industrial complex graphically.[36][37]

History[edit]

The existence of the medical-industrial complex as a concept is a product of the development of the modern American healthcare system. In the 19th century, the profession and practice of medicine underwent significant professionalization and growth.[38][39] Experimentation on enslaved people was common.[40] Doctors such as gynecologist J. Marion Sims operated on enslaved black women without anesthesia in order to document and develop gynecological medical issues and techniques to repair them.[40] The creation of hospitals to treat the sick create further disparities in favor of urban, white populations.[41]

The contemporary American healthcare system was shaped by the passage of the Hill-Burton Act, Medicare, Medicaid, and most recently, the Affordable Care Act.[42] The latter social programs attempt to diminish the disparity of populations with difficulties maintaining health insurance, but does not attempt to reduce the private sector.[43] The medical-industrial complex endeavors to reconcile the modern healthcare establishment with the long term health inequalities.

Some elements of the medical-industrial complex, including the experimentation on marginalized populations, were introduced much prior to the modern American healthcare system. The conglomerate as it is now known is the synthesis of the modern healthcare system with developed capitalism.

The Medical Industrial Complex Within the United States[edit]

Healthcare corporations[edit]

Pharmaceutical companies and chain hospitals are key healthcare corporations within the Medical Industrial complex.

Influence of pharmaceutical companies[edit]

Pharmaceutical companies are a leading influence in the expansion of the Medical-Industrial Complex.[45] Generic pharmaceutical drugs, which have the same chemical properties as branded, profitable drugs, are often sold for a fraction of the cost of their counterparts.[46] For example, a 10 mg dose of asthma medication Singulair can cost up to $250 per month, whereas its generic counterpart Montelukast costs only ~$20 per month.[47] Despite the inflated prices of brand-name drugs, pharmaceutical companies often induce bias in health care professionals by disproportionately promoting brand-name drugs.[48] For example, research has shown that pharmaceutical companies promote branded drugs more, making physicians more likely to prescribe an expensive medicine over a generic alternative.[49]

In addition to drugs, Laboratory Tests are also influenced by pharmaceutical company's vested interests. Physicians are more likely to order unnecessary tests when they are advertised by familiar pharmaceutical companies.[50] Like branded drugs, many pharmaceutical companies set these tests at inflated prices to increase profit.[50]

Influence of chain hospitals[edit]

Chain hospitals, in collaboration with pharmaceutical companies, also lead to the escalation of health costs.[51] A chain hospital is a subsidiary of a hospital network that works under a for-profit goal of expanding healthcare and establishing hospitals across a country, most notably the United States.[52] These corporations set standards regarding care administration, regulation, and enforcement – often without implementing a proper code of medical ethics.[53] Chain hospitals and other healthcare conglomerates hold a monopoly over health care costs within their hospitals and respective subsidiaries.[54] Thus, they can inflate healthcare costs with the goal of increasing profit, or lowering hospital standards to cut corners where necessary.[51]

This cost inflation is exacerbated by the fact that health care organizations are increasingly managed by business staff who often focus on economic gain, rather than local medical practitioners whose focus is patient benefit.[55] Moreover, hospitals in one state can be monitored by systems elsewhere, which gives significantly less power to local healthcare professionals.[56]

Bias in education[edit]

The curriculum of medical students often incorporates readings from large medical journals, like the New England Journal of Medicine.[57] These peer-reviewed journals may present results that favor expensive drugs manufactured by healthcare corporations or pharmaceutical companies, as these same corporations help to fund the journal.[58] As such, these large journals can perpetuate bias in healthcare providers' medication preferences by presenting results that are inherently influenced by the motives of businesses.[59]

Continuing medical education[edit]

Beyond medical school education, continuing medical education for healthcare is also subject to biased curriculum that disproportionately promotes the interest of its funders.[60] To continue practicing as a board-certified physician, a physician must take continuing medical education courses. Such programs ensure that physicians are up-to-date with new medicines and treatment plans.[61] However, these continuing education courses are often sponsored by pharmaceutical companies and healthcare corporations that can instill bias in physicians' education via the material provided.[62] For example, if a course is sponsored by a medical device company, then the coursework and exams used often reference using the company's medical device.[63] In turn, when the course is completed, it is more likely that physicians will use that medical device when interacting with patients regardless of if that medical device is necessary in the patients treatment.[63][60]

There are entities that work to reduce bias in continuing medical education courses, including the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education.[64] Other groups, like the Medical education agency, work to reduce the influence of pharmaceutical companies and hospital corporations in the continuing medical education process.[64]

Consequences[edit]

The MIC poses unique difficulties for patients and physicians. For patients dealing with wide-spread diseases, treatment often comes with steep prices in Medicare and insurance.[65] In recent 2020 health-care research, data has expressed how pandemics like COVID-19 have further tested the preparedness of the entire system's ability to combat a rapidly spreading virus.[65]

Patient-level[edit]

A health professional offers a unique service to patients, since patients often defer to the guidance and wisdom of their healthcare provider.[66] Many healthcare corporations are cognizant of the general population's lack of medical knowledge and possess the ability to set prices.[67] This unequal relationship between healthcare corporations and the populous is especially important as it involves the complex interaction between making a profit from a patient's suffering, but also physicians having to treat the patient as effectively as possible.[67] For patients who do not have access to reliable health insurance, this system imposes expensive medical treatment that they must pay for.[68]

For patients with a chronic illness, diagnosis often means expensive medications for the rest of one's life. Chronic illnesses like depression may require medications until the disease is treated, whereas more severe chronic illnesses like cystic fibrosis require expensive medical and pharmaceutical treatments for one's entire life.[69] These diseases could be treated, but their unique long-lasting nature means money can be generated from life-long treatments as opposed to a curative treatment.[68]

Individuals in low-income households and racial minority groups have experienced most of the impact of the high prices in the medical-industrial complex during the pandemic. Over one third of Latino adults or low-income adults were uninsured at some point during 2020.[70] In 2020, African Americans infected with COVID-19 died at a rate of 97.9 out of every 100,000, which is a death rate over twice as high as the death rates in white people (46.6/100,000) and Asians (40.4/100,000), and a third higher than Latinos (64.7/100,000).[70] Notably, the death rate of African Americans is comparable to that of Indigenous populations (81.9/100,000).[70]

Physician-level[edit]

Physicians are also subject to the medical-industrial complex and its manifestations. Throughout the 21st century, plastic surgery has become more common, a process where individuals undergo surgeries to resolve cosmetic issues.[71] Cosmetic surgeries are often used to satisfy a certain beauty standard.[72] For-profit healthcare promotes such non-essential healthcare services so that more profits can be created from healthy populations.[73]

The phrase "no margin, no mission" is often used to describe for-profit healthcare, where medical centers adapt to corporate interests.[72] For physicians, this can mean not treating uninsured patients, performing unnecessary procedures that generate profit, or supplying better care to patients when they have better means of pay.[71] For-profit healthcare can have great moral and ethical considerations for physicians who feel obligated to care more for well-insured patients as opposed to under-insured, vulnerable patients.[74]

Corporate entities, including insurance companies, also enforce standards surrounding medical treatment and payout.[72] These rules disregard ethical and moral dilemmas that physicians often face, setting unattainable guidelines for certain situations.[75] Physicians are often tied between healthcare corporations and insurance companies determining what they can and cannot do for a patient, regardless of if the treatment plan is necessary or not.[76]

Manufacturers of medical devices also fund medical education programs, physicians, and hospitals to encourage the use of their devices.[77] Many pharmaceutical and medical device companies are investor-based, meaning that if a device or drug receives FDA approval, investing physicians will be financially invested in the device's success or demise.[78][79] Thus, a physician who is financially involved in a product or service is more likely to promote or use the product, whether or not its efficacy is known.[80] This provides a conflict of interest for physicians, who may not provide their patients with effective, safe treatment due to bias for one product over another.[79]

Laws and policies[edit]

As indicated in Mia Mingus' diagram above, the "Medical Industrial Complex" is intertwined with the effects of economic policy on the practice of medicine. The Dalkon Shield is an interesting example of the conflict between economic profit and patient well being:

The Dalkon Shield was an IUD introduced in the late 1970's and 1980's.[81] The manufacturers of the device claimed that their IUD was safer than other forms of birth control available, and none of their reports noted any safety issues.[81] However, the long-term effects of the Dalkon Shield were not well known, and the IUD ended up being both ineffective and dangerous, resulting in many women becoming pregnant and facing severe pregnancy complications.[82] Moreover, because the device promised pregnancy prevention, many fetuses with severe birth defects were born as mothers did not follow medically-advised precautions during their pregnancy.[81] When the device was discontinued after CDC and FDA investigations, the IUDs was still not recalled and continued to endanger women who had them.[82] As such, the Dalkon Shield remained a dangerous medical device available in the healthcare market.[81][82]

Over a decade since the invention of the Dalkon Shield, the Safe Medical Devices Act of 1990 was passed by the FDA as an amendment to the FDCA.[83] This act required medical device manufacturer to report any information about medical devices that could contribute to death, sickness, or injury. As such, healthcare professionals were required to report malfunctioning or unsafe medical equipment.[84]

Additionally, the Physician Payments Sunshine Act, created by the United States Department of Justice, declared that all contracts that medical device companies make with physicians must be made public.[85] As such, this act could prevent future physicians from promoting or overusing medical devices on patients to further personal interests over patient benefit.[85]

In other countries[edit]

The healthcare system in the United States performs worse on health indicators compared to other major nations, despite the country's higher investment in healthcare.[86] This is reflected in lower ratings for life expectancy and satisfaction among U.S. citizens.[87] Some argue that these lower ratings are partly due to the fact that the United States does not provide universal health coverage, unlike many other nations.[88][87] Some major differences between the United States and other major countries include quality, access, efficiency, equity, and life expectancy.[87]

White Savior Industrial Complex (WSIC)[edit]

See also: White savior

Countries in the Global South do not always have the same amount and quality of resources as countries in the Global North.[89] Due to these disparities, scholars argue that the White Savior Industrial Complex (WSIC) has influenced healthcare systems on individual, interpersonal, structural, and global levels.[89] Coined by Teju Cole, the WSIC refers to the phenomenon where privileged white individuals seek personal fulfillment by trying to "liberate, rescue, or otherwise uplift underprivileged people of color."[89][90] According to this concept, people with a white savior mentality may believe they know what is best for other countries, although such individuals often end up causing more harm than good. One such example describes how a white American physician caused Ugandan medical staff to doubt their knowledge and ability in delivering a baby.[89] Another example recounts how a White male physician used his privilege to influence medical staff in India to subvert their traditional medical practices.[89] Scholars cite these anecdotes as examples of how widespread the WSIC has become.[89]

India[edit]

Some individuals claim that the medical-industrial complex also exists in India, where the Indian Medical Association lobbies for their interests in local and state politics.[91] Specifically, some doctors have accused the Indian Medical Association of engaging in unethical practices and obstructing the advancement of healthcare systems within the medical profession.[92] The Indian Medical Association has responded to these claims by stating that their critics exaggerate rare occasions of unethical practices.[92] Yet, some doctors have privately admitted to immoral actions and have stated that these practices are not limited to a few individual patients.[92] Ethics is a contentious topic both within and beyond the medical profession. Claims of unethical practices may stem from the stark contrast between healthcare systems ranging from tall, high-tech hospitals to dilapidated, dirty ones.[93] Some medical professionals and scholars suggest that stricter office guidelines may decrease unethical practices, but this could also raise the cost of healthcare for patients.[92]

Brazil[edit]

In Brazil, scholars refer to the medical-industrial complex as the "healthcare-industrial complex."[94] The healthcare-industrial complex also expands beyond Brazil, where internal infrastructure fails to meet medical demands, leaving patients unable to access necessary products and services.[94][95] Scholars argue that Brazil's medical history reflects poor distribution of social and economic medical policies, resulting in underdeveloped and underfunded healthcare sectors in poor communities.[96] The Program for Investment in the Health Industrial Complex, or PROCIS, funds medical research in Brazil to advance the country's global presence in pharmaceutical and medical industries.[97][96] According to the Brazilian Ministry of Health, PROCIS was formed with the goal of developing Brazil's internal healthcare structure and promoting research, development, and treatment.[98] Over 100 billion Brazilian reals have been devoted to supporting medical research efforts, development of the medical industry, and innovating existing medical products.[99] The PROCIS also established a margin of preference on healthcare products that are nationally funded and sourced.[100]

Cultural Criticisms[edit]

A group of scholars and activists offer critiques and alternative approaches to the medical-industrial complex.

Alternative approaches[edit]

Alternative approaches to the medical-industrial complex incorporate elements from different theoretical frameworks and practices, such as holism, environmentalism, reproductive justice, the disability rights movement, feminism, and other related concepts.[101][102] These alternative approaches stem from the collective efforts of historically marginalized activists facing structural violence, including Indigenous, Black, and migrant communities.[103] According to various scholars, these alternative approaches aim to reimagine health as a holistic concept that extends beyond the traditional focus of the medical-industrial complex to include the body, mind, and spirit.[101][102][104] Furthermore, these alternative approaches challenge the medicalization of illness and disease by highlighting how structural factors shape health, rather than just individual behaviors.[103][104][105][106] Alternative approaches to the medical-industrial complex also challenge the boundaries between patient and provider to encourage collaboration between the two and to center the lived experiences of individuals in the healing process.[101][102][104][106] Additionally, they highlight the importance of forming caring relationships within one’s community to establish a sense of solidarity among individuals as equal participants in the healing process.[101]

Another alternative approach to the MIC is mindfulness, which emphasizes how the resources and tools for healing exist within the self and not within the solutions offered by the medical-industrial complex.[107] Another distinct approach from the medical-industrial complex is alternative health, which incorporates elements of traditional medicine and focuses on addressing underlying factors of disease rather than merely treating symptoms.[108] Alternative health, as a new social movement, provides a space for individuals and communities with diverse lived experiences to actively participate in the healthcare system while emphasizing their humanity in the healing process.[109] Scholars Jonathan Metzl and Helena Hansen advocate for a new approach to medical education in the United States, termed structural competency, which entails clinicians' ability to comprehend and address social determinants of health during patient interactions.[110]

See also[edit]

- Ableism

- Compulsory sterilization

- Conflict of interest

- Continuing medical education

- Conflict of interest in the healthcare industry

- Disability Studies

- Eli Clare

- Eugenics

- Francis Galton

- For-profit hospital

- Healthcare in the United States

- Healthcare in Brazil

- List of industrial complexes

- Medicalization

- Medicine

- Mia Mingus

- Poverty and health in the United States

- Social determinants of health

- Scientific racism

- Social model of disability

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Wohl, Stanley. The Medical Industrial Complex / Stanley Wohl. First edition. New York: Harmony Book, 1984: 85–98

- ^ Levy, Robert M. (March 2012). "The Extinction of Comprehensive Pain Management: A Casualty of the Medical-Industrial Complex or an Outdated Concept?". Neuromodulation: Technology at the Neural Interface. 15 (2): 89–91. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1403.2012.00444.x. PMID 22487596. S2CID 30492373.

- ^ a b Global Health Watch 5: An Alternative World Health Report (1st ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing. 2017. pp. 106–117. ISBN 9781786992260.

- ^ Wallace, Gwendolyn (2020-07-08). "To Abolish the Medical industrial Complex". Black Agenda Report. Retrieved 2024-04-22.

- ^ a b "Medical Industrial Complex Visual". Leaving Evidence. 2015-02-06. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

- ^ "Beyond J. Marion Sims: Black Women Have Been Fighting Discrimination in the Medical Industrial Complex for Centuries". CRWNMAG. 2018-04-20. Retrieved 2024-04-22.

- ^ Woodland, Sonia Sarkar, Cara Page, Erica (2023-04-18). "Healing Justice Lineages: Disrupting the Medical-Industrial Complex". Non Profit News | Nonprofit Quarterly. Retrieved 2024-04-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Medicalizing Blackness | Rana A. Hogarth". University of North Carolina Press. Retrieved 2024-04-05.

- ^ "How Nature contributed to science's discriminatory legacy". Nature. 609 (7929): 875–876. 2022-09-28. doi:10.1038/d41586-022-03035-6. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Ehrenreich, John; Ehrenreich, Barbara (1970-12-17). "The Medical-Industrial Complex". The New York Review of Books. Vol. 15, no. 11. ISSN 0028-7504. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

- ^ a b Lexchin, J. (29 May 2003). "Pharmaceutical industry sponsorship and research outcome and quality: systematic review". BMJ. 326 (7400): 1167–1170. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7400.1167. PMC 156458. PMID 12775614.

- ^ Xu, Amy L; Jain, Amit; Humbyrd, Casey Jo (September 2022). "Ethical Considerations Surrounding Surgeon Ownership of Ambulatory Surgery Centers". Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 235 (3): 539–543. doi:10.1097/XCS.0000000000000271. PMID 35972176. S2CID 251592849.

- ^ "Wohl's Bitter Medicine". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2022-10-17.

- ^ Baggish, Michaels; Nezhat, Camran (1992). "The Medical–Industrial Complex". Journal of Gynecologic Surgery. 8 (3): v–vi. doi:10.1089/gyn.1992.8.v.

- ^ Levitsky, Sidney (February 2007). "Navigating the New 'Flat World' of Cardiothoracic Surgery". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 83 (2): 361–369. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.10.100. PMID 17257949.

- ^ Pattison, Robert V.; Katz, Hallie M. (11 August 1983). "Investor-Owned and Not-for-Profit Hospitals: A Comparison Based on California Data". New England Journal of Medicine. 309 (6): 347–353. doi:10.1056/NEJM198308113090606. PMID 6346098.

- ^ Singleton, Kathleen A.; Dever, Rosemary; Donner, Terry A. (May 1992). "The Safe Medical Device Act: Nursing Implications". Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing. 11 (3): 141–144. doi:10.1097/00003465-199205000-00003. PMID 1597102.

- ^ Congress.gov. "H.R.3095 – 101st Congress (1989–1990): Safe Medical Devices Act of 1990." November 28, 1990. http://www.congress.gov/ .

- ^ Mudur, Ganapati (2012). "Doctors criticise Indian Medical Association for ignoring unethical practice". BMJ: British Medical Journal. 344 (7863): 6. doi:10.1136/bmj.e4256. ISSN 0959-8138. JSTOR 23281304. PMID 22736468. S2CID 10709257.

- ^ Kasthuri, Arvind (July–September 2018). "Challenges to Healthcare in India – The Five A's". Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 43 (3): 141–143. doi:10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_194_18. PMC 6166510. PMID 30294075.

- ^ Dias, Otávio (April 7, 2021). "The Healthcare Industrial Complex in Brazil: Challenges and solutions for the future".

- ^ Temporão, José Gomes, and Carlos Augusto Grabois Gadelha. "The Health Economic-Industrial Complex (HEIC) and a New Public Health Perspective." Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Global Public Health. 29 July 2019; Accessed 5 November 2022. https://oxfordre.com/publichealth/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190632366.001.0001/acrefore-9780190632366-e-27 .

- ^ Rogers, Chrissie; Weller, Susie, eds. (25 June 2012). Critical Approaches to Care: Understanding Caring Relations, Identities and Cultures. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203112083. ISBN 9780415613293.

- ^ Denbow, Jennifer; Spira, Tamara Lea (2023). "Shared Futures or Financialized Futures: Polygenic Screening, Reproductive Justice, and the Radical Charge of Collective Care". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 49 (1): 209–235. doi:10.1086/725832. ISSN 0097-9740.

- ^ Barker, Kristin K. (April 2014). "Mindfulness Meditation: Do-It-Yourself Medicalization of Every Moment". Social Science & Medicine. 106: 168–176. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.024. ISSN 0277-9536.

- ^ Coleman, Michel P. (2013). "War on Cancer and the Influence of the Medical-Industrial Complex". Journal of Cancer Policy. 1 (3–4): e31–e34. doi:10.1016/j.jcpo.2013.06.004. ISSN 2213-5383.

- ^ Nissen, Nina (2011). "Challenging Perspectives: Women, Complementary and Alternative Medicine, and Social Change" (PDF). Interface: A Journal for and About Social Movements. 3 (2): 187–212 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Schneirov, Matthew; Geczik, Jonathan David (2003). A diagnosis for our times: alternative health, from lifeworld to politics. SUNY series in the sociology of culture. Albany: State University Press of New York. ISBN 978-0-7914-5731-3.

- ^ Metzl, Jonathan M.; Hansen, Helena (2014). "Structural competency: Theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality". Social Science & Medicine. 103: 126–133. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.032.

- ^ "President Dwight D. Eisenhower's Farewell Address (1961) | National Archives". www.archives.gov. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

- ^ Bacevich, Andrew J., ed. (2009). The long war: a history of U.S. national security policy since World War II. New York Chichester: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13159-9.

- ^ a b c d Ehrenreich, John; Ehrenreich, Barbara (1970-12-17). "The Medical-Industrial Complex". The New York Review of Books. Vol. 15, no. 11. ISSN 0028-7504. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

- ^ a b c Relman, Arnold S. (1980-10-23). "The New Medical-Industrial Complex". New England Journal of Medicine. 303 (17): 963–970. doi:10.1056/NEJM198010233031703. ISSN 0028-4793.

- ^ Steinwald, Bruce; Neuhauser, Duncan (1970). "The Role of the Proprietary Hospital". Law and Contemporary Problems. 35 (4): 817–838. doi:10.2307/1190951. ISSN 0023-9186.

- ^ a b "Terms Defined". HJC. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

- ^ "Medical Industrial Complex Visual". Leaving Evidence. 2015-02-06. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

- ^ "About". Leaving Evidence. 2009-10-29. Retrieved 2024-04-22.

- ^ "Medicalizing Blackness | Rana A. Hogarth". University of North Carolina Press. Retrieved 2024-04-05.

- ^ Rusert, Britt (2017). Fugitive science: empiricism and freedom in early African American culture. America and the long 19th century. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-1-4798-8568-8.

- ^ a b Spettel, Sara; White, Mark Donald (2011-06-01). "The Portrayal of J. Marion Sims' Controversial Surgical Legacy". Journal of Urology. 185 (6): 2424–2427. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2011.01.077. ISSN 0022-5347.

- ^ Breslaw, Elaine G (March 2014). Lotions, Potions, Pills, and Magic: Health Care in Early America. NYU Press. ISBN 9781479807048.

- ^ Shi, Lieyu; Singh, Douglas (2019). Delivering Health Care in America: A Systems Approach (7th ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 9781284124491.

- ^ Thomasson, Melissa A. (July 2002). "From Sickness to Health: The Twentieth-Century Development of U.S. Health Insurance". Explorations in Economic History. 39 (3): 233–253. doi:10.1006/exeh.2002.0788.

- ^ SDI, Samarra - Dec 21, 2019 08.jpg

- ^ Lexchin, J. (29 May 2003). "Pharmaceutical industry sponsorship and research outcome and quality: systematic review". BMJ. 326 (7400): 1167–1170. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7400.1167. PMC 156458. PMID 12775614.

- ^ McCormack, James; Chmelicek, John T. (October 2014). "Generic versus brand name: the other drug war". Canadian Family Physician. 60 (10): 911. PMC 4196814. PMID 25316744.

- ^ "UpToDate". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 2022-10-17.[full citation needed]

- ^ Wohl, Stanley. The Medical Industrial Complex / Stanley Wohl. First edition. New York: Harmony Book, 1984: 85–98

- ^ Jupiter, Jesse; Burke, Dennis (2013). "Scott's parabola and the rise of the medical–industrial complex". HAND. 8 (3): 249–252. doi:10.1007/s11552-013-9526-5. ISSN 1558-9447. PMC 3745238. PMID 24426930.

- ^ a b Pattison, Robert V.; Katz, Hallie M. (11 August 1983). "Investor-Owned and Not-for-Profit Hospitals: A Comparison Based on California Data". New England Journal of Medicine. 309 (6): 347–353. doi:10.1056/NEJM198308113090606. PMID 6346098.

- ^ a b Wohl, Stanley. The Medical Industrial Complex / Stanley Wohl. First edition. New York: Harmony Book, 1984: 85–98

- ^ "Wohl's Bitter Medicine". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2022-10-17.

- ^ Levy, Robert M. (March 2012). "The Extinction of Comprehensive Pain Management: A Casualty of the Medical-Industrial Complex or an Outdated Concept?". Neuromodulation: Technology at the Neural Interface. 15 (2): 89–91. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1403.2012.00444.x. PMID 22487596. S2CID 30492373.

- ^ Lábaj, Martin; Silanič, Peter; Weiss, Christoph; Yontcheva, Biliana (November 2018). "Market structure and competition in the healthcare industry: Results from a transition economy" (PDF). The European Journal of Health Economics. 19 (8): 1087–1110. doi:10.1007/s10198-018-0959-1. PMID 29445942.

- ^ Maloney, FP (1998). "The emerging medical/industrial complex. The industrialization of medicine". Physician Executive. 24 (2): 34–8. PMID 10180498.

- ^ Jupiter, Jesse; Burke, Dennis (2013). "Scott's parabola and the rise of the medical–industrial complex". HAND. 8 (3): 249–252. doi:10.1007/s11552-013-9526-5. ISSN 1558-9447. PMC 3745238. PMID 24426930.

- ^ Levitsky, Sidney (February 2007). "Navigating the New 'Flat World' of Cardiothoracic Surgery". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 83 (2): 361–369. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.10.100. PMID 17257949.

- ^ Schofferman, Jerome (2011). "The Medical-Industrial Complex, Professional Medical Associations, and Continuing Medical Education". Pain Medicine. 12 (12): 1713–1719. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01282.x. PMID 22145759.

- ^ Wohl, Stanley. The Medical Industrial Complex / Stanley Wohl. First edition. New York: Harmony Book, 1984: 85–98

- ^ a b Schofferman, Jerome (2011). "The Medical-Industrial Complex, Professional Medical Associations, and Continuing Medical Education". Pain Medicine. 12 (12): 1713–1719. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01282.x. PMID 22145759.

- ^ "What is CME Credit?". National Institutes of Health (NIH). 2017-03-20. Retrieved 2022-10-22.

- ^ Pattison, Robert V.; Katz, Hallie M. (11 August 1983). "Investor-Owned and Not-for-Profit Hospitals: A Comparison Based on California Data". New England Journal of Medicine. 309 (6): 347–353. doi:10.1056/NEJM198308113090606. PMID 6346098.

- ^ a b Wohl, Stanley. The Medical Industrial Complex / Stanley Wohl. First edition. New York: Harmony Book, 1984: 85–98

- ^ a b Morris, Lewis; Taitsman, Julie K. (17 December 2009). "The Agenda for Continuing Medical Education — Limiting Industry's Influence". New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (25): 2478–2482. doi:10.1056/NEJMsb0905411. PMID 20018969.

- ^ a b Geyman, John (April 2021). "COVID-19 Has Revealed America's Broken Health Care System: What Can We Learn?". International Journal of Health Services. 51 (2): 188–194. doi:10.1177/0020731420985640. ISSN 0020-7314. PMID 33435794. S2CID 231596061.

- ^ Grouse, Lawrence (September 2014). "Cost-effective medicine vs. the medical-industrial complex". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 6 (9): E203–E206. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.09.01. PMC 4178073. PMID 25276402.

- ^ a b Relman, Arnold S. (24 September 2009). "Doctors as the Key to Health Care Reform". New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (13): 1225–1227. doi:10.1056/NEJMp0907925. PMID 19776404.

- ^ a b Wohl, Stanley. The Medical Industrial Complex / Stanley Wohl. First edition. New York: Harmony Book, 1984: 85–98

- ^ Lexchin, J. (29 May 2003). "Pharmaceutical industry sponsorship and research outcome and quality: systematic review". BMJ. 326 (7400): 1167–1170. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7400.1167. PMC 156458. PMID 12775614.

- ^ a b c Vasquez, Reyes M (December 2020). "The Disproportional Impact of COVID-19 on African Americans. Health and human rights". Health and Human Rights Journal. 22 (2): 299–307.

- ^ a b Wohl, Stanley. The Medical Industrial Complex / Stanley Wohl. First edition. New York: Harmony Book, 1984: 85–98

- ^ a b c Grouse, Lawrence (September 2014). "Cost-effective medicine vs. the medical-industrial complex". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 6 (9): E203–E206. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.09.01. PMC 4178073. PMID 25276402.

- ^ Arab, Khalid; Barasain, Omar; Altaweel, Abdullah; Alkhayyal, Jawaher; Alshiha, Lulwah; Barasain, Rana; Alessa, Rania; Alshaalan, Hayfaa (August 2019). "Influence of Social Media on the Decision to Undergo a Cosmetic Procedure". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery – Global Open. 7 (8): e2333. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000002333. PMC 6756652. PMID 31592374.

- ^ Christensen, Richard C. (2005). "No Margin, No Mission: Health Care Organizations and the Quest for Ethical Excellence (review)". Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 16 (1): 168–170. doi:10.1353/hpu.2005.0006. S2CID 72636747.

- ^ Jupiter, Jesse; Burke, Dennis (2013). "Scott's parabola and the rise of the medical–industrial complex". HAND. 8 (3): 249–252. doi:10.1007/s11552-013-9526-5. ISSN 1558-9447. PMC 3745238. PMID 24426930.

- ^ Poduval, Murali; Poduval, Jayita (2008). "Medicine as a Corporate Enterprise: A Welcome Step?". Mens Sana Monographs. 6 (1): 157–174. doi:10.4103/0973-1229.34714 (inactive 2024-02-01). PMC 3190548. PMID 22013357.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of February 2024 (link) - ^ Baggish, Michaels; Nezhat, Camran (1992). "The Medical–Industrial Complex". Journal of Gynecologic Surgery. 8 (3): v–vi. doi:10.1089/gyn.1992.8.v.

- ^ Maloney, FP (1998). "The emerging medical/industrial complex. The industrialization of medicine". Physician Executive. 24 (2): 34–8. PMID 10180498.

- ^ a b Xu, Amy L; Jain, Amit; Humbyrd, Casey Jo (September 2022). "Ethical Considerations Surrounding Surgeon Ownership of Ambulatory Surgery Centers". Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 235 (3): 539–543. doi:10.1097/XCS.0000000000000271. PMID 35972176. S2CID 251592849.

- ^ Levy, Robert M. (March 2012). "The Extinction of Comprehensive Pain Management: A Casualty of the Medical-Industrial Complex or an Outdated Concept?". Neuromodulation: Technology at the Neural Interface. 15 (2): 89–91. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1403.2012.00444.x. PMID 22487596. S2CID 30492373.

- ^ a b c d "The Dalkon Shield | The Embryo Project Encyclopedia". embryo.asu.edu. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- ^ a b c Kolata, Gina (6 December 1987). "THE SAD LEGACY OF THE DALKON SHIELD". The New York Times.

- ^ Congress.gov. "H.R.3095 – 101st Congress (1989–1990): Safe Medical Devices Act of 1990." November 28, 1990. http://www.congress.gov/ .

- ^ Singleton, Kathleen A.; Dever, Rosemary; Donner, Terry A. (May 1992). "The Safe Medical Device Act: Nursing Implications". Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing. 11 (3): 141–144. doi:10.1097/00003465-199205000-00003. PMID 1597102.

- ^ a b Vox, Ford (29 June 2010). "The Medical-Industrial Complex". The Atlantic.

- ^ Gunja, Munira Z.; Gumas, Evan D.; Williams II, Reginald D. (2023-01-31). "U.S. Health Care from a Global Perspective, 2022: Accelerating Spending, Worsening Outcomes". www.commonwealthfund.org. doi:10.26099/8ejy-yc74. Retrieved 2024-02-27.

- ^ a b c Davis, Karen; Stremikis, Kristof; Squires, David; Schoen, Cathy (2014-06-16). "Mirror, Mirror on the Wall, 2014 Update: How the U.S. Health Care System Compares Internationally". www.commonwealthfund.org. doi:10.26099/9q4x-na97. Retrieved 2023-04-30.

- ^ Estes, Carroll L.; Harrington, Charlene; Pellow, David N. (2001), Social Policy & Aging: A Critical Perspective, Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc., pp. 165–186, doi:10.4135/9781452232676, ISBN 9780803973466, retrieved 2023-04-30

- ^ a b c d e f Initiative, HEAL (2020-04-16). "The White Savior Industrial Complex in Global Health". Voices from the Frontline. Retrieved 2023-04-30.

- ^ Aslan, Reza (2022-10-20). "How to Avoid the 'White Savior Industrial Complex'". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

- ^ Prasad, Purendra, and Amar Jesani. "Equity and Access : Health Care Studies in India / Edited by Purendra Prasad and Amar Jesani." edited by Purendra Prasad and Amar Jesani. First edition. New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Mudur, Ganapati (2012). "Doctors criticise Indian Medical Association for ignoring unethical practice". BMJ: British Medical Journal. 344 (7863): 6. doi:10.1136/bmj.e4256. ISSN 0959-8138. JSTOR 23281304. PMID 22736468. S2CID 10709257.

- ^ Kasthuri, Arvind (July–September 2018). "Challenges to Healthcare in India – The Five A's". Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 43 (3): 141–143. doi:10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_194_18. PMC 6166510. PMID 30294075.

- ^ a b Dias, Otávio (April 7, 2021). "The Healthcare Industrial Complex in Brazil: Challenges and solutions for the future".

- ^ Temporão, José Gomes, and Carlos Augusto Grabois Gadelha. "The Health Economic-Industrial Complex (HEIC) and a New Public Health Perspective." Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Global Public Health. 29 July 2019; Accessed 5 November 2022. https://oxfordre.com/publichealth/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190632366.001.0001/acrefore-9780190632366-e-27 .

- ^ a b Mazuka, Valbona (2019). "Interrupted Constructions: The Brazilian Health-Industrial Complex in Historical Perspective". Latin American Perspectives. 46 (4): 186–209. doi:10.1177/0094582X17750149. S2CID 148796066.

- ^ Viana, Ana Luiza; Pacifico da Silva, Hudson; Ibañez, Nelson; Iozzi, Fabíola (2016). "Development policy for the Brazilian health industry and qualification of national public laboratories". Cad. Saúde Pública. 32 (Suppl 2): S1–S14. doi:10.1590/0102-311X00188814. PMID 27828684.

- ^ "Programa para o Desenvolvimento do Complexo Industrial da Saúde (PROCIS)". Ministério da Saúde (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 2022-11-05.

- ^ https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/composicao/sctie/cgcis/procis/projetos-do-procis/projetos-vigentes-cgcis.pdf

- ^ "Development of Industrial Health Complex Program – PROCIS". The Brazil Business. 4 May 2015. Retrieved 2022-11-08.

- ^ a b c d Rogers, Chrissie; Weller, Susie, eds. (25 June 2012). Critical Approaches to Care: Understanding Caring Relations, Identities and Cultures. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203112083. ISBN 9780415613293.

- ^ a b c Schneirov, Matthew; Geczik, Jonathan David (September 1996). "A Diagnosis for Our Times: Alternative Health's Submerged Networks and the Transformation of Identities". The Sociological Quarterly. 37 (4): 627–644. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.1996.tb01756.x. ISSN 0038-0253.

- ^ a b Denbow, Jennifer; Spira, Tamara Lea (2023). "Shared Futures or Financialized Futures: Polygenic Screening, Reproductive Justice, and the Radical Charge of Collective Care". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 49 (1): 209–235. doi:10.1086/725832. ISSN 0097-9740.

- ^ a b c Barker, Kristin K. (April 2014). "Mindfulness Meditation: Do-It-Yourself Medicalization of Every Moment". Social Science & Medicine. 106: 168–176. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.024. ISSN 0277-9536.

- ^ Coleman, Michel P. (2013). "War on Cancer and the Influence of the Medical-Industrial Complex". Journal of Cancer Policy. 1 (3–4): e31–e34. doi:10.1016/j.jcpo.2013.06.004. ISSN 2213-5383.

- ^ a b Nissen, Nina (2011). "Challenging Perspectives: Women, Complementary and Alternative Medicine, and Social Change" (PDF). Interface: A Journal for and About Social Movements. 3 (2): 187–212 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Barker, Kristin K. (April 2014). "Mindfulness Meditation: Do-It-Yourself Medicalization of Every Moment". Social Science & Medicine. 106: 168–176. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.024. ISSN 0277-9536.

- ^ Schneirov, Matthew; Geczik, Jonathan David (September 1996). "A Diagnosis for Our Times: Alternative Health's Submerged Networks and the Transformation of Identities". The Sociological Quarterly. 37 (4): 627–644. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.1996.tb01756.x. ISSN 0038-0253.

- ^ Schneirov, Matthew; Geczik, Jonathan David (2003). A diagnosis for our times: alternative health, from lifeworld to politics. SUNY series in the sociology of culture. Albany: State University Press of New York. ISBN 978-0-7914-5731-3.

- ^ Metzl, Jonathan M.; Hansen, Helena (2014). "Structural competency: Theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality". Social Science & Medicine. 103: 126–133. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.032.

Further reading[edit]

- Geyman, John P. (2004-01-01). The Corporate Transformation of Health Care: Can the Public Interest Still Be Served?. Springer Publishing Company. ISBN 9780826124678. Retrieved 2015-05-14.

- Ismail, Asif (2011). "Bad For Your Health: The U.S. Medical Industrial Complex Goes Global". In Steven Best; Richard Kahn; Anthony J. Nocella II; Peter McLaren (eds.). The Global Industrial Complex: Systems of Domination. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 211–232. ISBN 978-0739136980.

- Rosenthal, Elisabeth (2017). An American Sickness: How Healthcare Became Big Business and How You Can Take it Back. Penguin Press. ISBN 9780698407183.

- Schatman, Michael E. (2011). "The Medical-Industrial Complex and Conflict of Interest in Pain Education". Pain Medicine. 12 (12): 1710–1712. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01284.x. PMID 22168303.