Naewat-dang shamanic paintings

33°30′30″N 126°30′40″E / 33.50833°N 126.51111°E

| Naewat-dang shamanic paintings | |

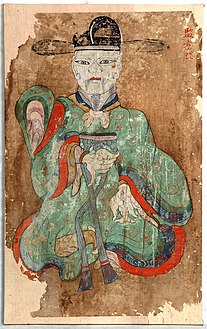

Portrait of the village deity Jeseok | |

| Korean name | |

|---|---|

| Hangul | 내왓당 무신도 |

| Hanja | 내왓堂巫神圖 |

| Revised Romanization | Naewat-dang musindo |

| McCune–Reischauer | Naewat-tang musindo |

The Naewat-dang shamanic paintings are ten portraits of village patron gods formerly hung at the Naewat-dang shrine, one of the four state-recognized shamanic temples of Jeju Island, now in South Korea. The shrine was destroyed in the nineteenth century, and the works are currently preserved at Jeju National University as a government-designated Important Folklore Cultural Property. They may be the oldest Korean shamanic paintings currently known.

Although twelve gods were worshipped at Naewat-dang, only ten paintings survive. They are all painted with mineral-based pigments on Korean paper with an ink brush, perhaps by the same painter. They depict six male and four female deities, who are dressed in various headgear, robes, and shoes and usually hold a fan. The attire of the gods can sometimes be linked to their names, or to the shamanic myths told about them. For instance, a god said to come from the Central Asian Western Regions wears an unusual hat that may be based on a turban, while the youngest goddess wears the loose hair of an unmarried woman.

The existence of paintings at Naewat-dang is attested since 1466, when some portraits at the shrine were burnt; these may be the two currently missing works. Whether the paintings present in 1466 survived a large-scale persecution of shamanism in 1702 is unknown, but even if they were destroyed, they were probably quickly repainted once the persecution had ended a year later. Analyses of the gods' attire suggest a date of composition in or before the 17th century.

The works are highly divergent from mainland Korean shamanic paintings, and also unusual in that Jeju Island shamanism usually does not involve paintings. Unlike the human-like gods of mainland portraits, the Naewat-dang deities appear inhuman and grotesque, reminiscent of the hybrid human-tree deities worshipped in some Jeju villages. The paintings also invoke both snake and bird imagery.

Introduction[edit]

In many mainland traditions of Korean shamanism, portraits of the gods are hung in a shrine room above the altar. These works hold great religious significance, being both the objects of daily worship and a medium by which the depicted deity sends forth divine inspiration, to the point that "the shaman does not venture to touch them without first making offerings and petitioning the gods, requesting their indulgence". Some shamans go as far as to not distinguish the painting and the god, at least in speech.[1] Shamans regularly replace damaged works and replace old paintings with new ones as a way to express gratitude to the depicted gods.[2] As a result, mainland shamanic paintings from even the 18th century are extremely rare, and ones from before then are unattested.[1][3] Mainland works generally mimic the mainstream Chinese-style or Buddhist paintings.[4] Indeed, many shamanic portraits were actually painted by "goldfish monks": Buddhist priests trained in Buddhist temple art.[5]

Compared to the mainland paintings, the portraits of the Jeju Island Naewat-dang shrine are exceptional in both antiquity—they may be the oldest shamanic paintings yet discovered—and distinctiveness of style.[6] However, paintings are not generally part of Jeju ritual practice, and the Naewat-dang works are thus unusual. Many reasons have been suggested for the lack of shamanic paintings on the island, including a tradition of offering worship in exposed environments such as forests and caverns rather than inside buildings;[7] the impoverished state of the island during the Joseon era (1392–1910) which made materials difficult to afford; and the fact that the local Buddhist tradition had gone nearly extinct under persecution by the Neo-Confucian Joseon state, so that there remained very few goldfish monks.[8] The physical representations of the gods in Jeju shamanism are usually cut paper figurines called gime.[9][10]

Mythology[edit]

The village-shrine bon-puri (shamanic narrative associated with village patron gods) of Naewat-dang is of the incipient type, meaning that shamans recite only the names of the village's patron gods without an accompanying myth concerning them.[11] The bon-puri refers to twelve gods, but only ten or eleven are actually named.[12][13] They are the following:[12][13]

| Korean name | Transliteration | Translation | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 제석천왕(帝釋天王)마노라 | Jeseok-cheonwang-manora | Lord Jeseok, King of Heaven | Portraits hung towards the more honored north side | Male | |

| 본궁전(本宮前) | Bon'gung-jeon | Front of the Original Palace | Female | Sometimes omitted in the bon-puri | |

| 어모라 원망(冤望)님 | Eomora Wonmang-nim | Eomora Resentment | Male | ||

| 수랑상태자(水靈上太子)마노라 | Surang-sangtaeja-manora | Lord High Prince of the Spirit of Water | |||

| 내외천자도(內外天子道)마노라 | Naeoe-cheonjado-manora | Lord Deity the Inner and Outer Son of Heaven | Portraits hung towards the west side | ||

| 감찰지방관(監察地方官)한집마노라 | Gamchal-jibanggwan-han-jip-manora | Lord of the Great House, Regional Officer of the Censorate | Said to have come from Ora upstream of Naewat-dang | ||

| 상사대왕(上事大王) | Sangsa-daewang | Great King of High Affairs | Said to have come from the Western Regions | ||

| 중전대부인(中殿大夫人) | Jungjeon-daebuin | Great Wife of the Queen's Residence | Female | ||

| 정절상군(軍)농 | Jeongjeol-sanggunnong | Perhaps "Uppermost Lady of Chastity"[3] | |||

| ᄌᆞ지홍이아기씨 | Jajihong'i-agissi | Red Girl | |||

| 내외불도마노라 | Naeoe-buldo-manora | Inner and Outer Lord Deity of Fertility | No painting. Possibly a pair of deities.[14] | ||

Unknown twelfth deity

| |||||

Several of these gods also appear in the village-shrine bon-puri of Gung-dang shrine, which was formed following a schism from the Naewat-dang shrine.[3] According to the Gung-dang bon-puri, which includes mythological narratives, Sangsa-daewang has two wives: Jungjeon-daebuin, his primary spouse, and Jeongjeol-sanggunnong, his lesser wife. When the latter is pregnant, she has a craving for pork, a ritually impure meat. The goddess is burning pig hair to at least smell the scent of pork when Sangsa-daewang arrives. After realizing what Jeongjeol-sanggunnong is doing, he expels both of his wives to Gung-dang. Jeongjeol-sanggunnong gives birth to seven daughters there,[15] of whom the youngest is Jajihong'i-agissi.[16] At Gung-dang, Jungjeon-daebuin is worshipped with rice and wine as a goddess of fertility, while pork is offered for Jeongjeol-sanggunnong.[15]

The Gungdang bon-puri also features Cheonjado, equivalent to Naeoe-cheonjado-manora in the Naewat-dang bon-puri. According to the narrative, Cheonjado is born to two deities, neither of whom are worshipped at Naewat-dang specifically. His father Socheon'guk emerges from Jeju Island, while his mother Baekju-manura is born in China. At the age of fifteen, the latter sails to Jeju and marries Socheon'guk. They have eighteen sons and twenty-eight daughters. Due to the large number of children to feed, Baekju-manura—who is newly pregnant with Cheonjado—suggests that Socheon'guk take up farming. But the hungry god devours all of his plowing oxen and even his neighbor's oxen, and begins to plow the fields with his stomach. At this, Baekju-manura divorces him.[17] When Cheonjado is born, Baekju-manura takes him to Socheon'guk, who imprisons him in an iron chest which he throws into the sea. After six years, it sinks into the underwater realm of the Dragon King. The Dragon King's youngest daughter opens the chest and finds the handsome Cheonjado reading a book inside. She marries Cheonjado, but her husband eats so much everyday that it bankrupts the Dragon King's realm. The King finally expels the two, and they go to China, where Cheonjado suppresses a rebellion. In return for his service, the Jade Emperor allows him to become a god at Naewat-dang.[18]

The motifs of the Gung-dang bon-puri, such as gods with multiple wives, conflicts over eating habits, and the abandonment of a child into the sea, are typical of Jeju village-shrine myths.[19]

Physical description[edit]

The ten surviving paintings are all drawn with mineral-derived deep-color pigments (jinchae) on Korean paper[20] using an ink brush, with gold leaf in parts.[21] The colors used are the Five Intermediary Colors, excluding violet, as well as black and white.[22] Various motifs were apparently added by screen printing.[23] The paintings were originally attached to pinewood frames, although they are now preserved in a chest.[20] The paintings' dimensions are between 63 and 64 centimeters vertically and 39 and 39.5 centimeters horizontally (25 × 15½ inches).[21] The style is consistent throughout the ten paintings, perhaps because they were drawn by the same painter[24] or because the deities were conceived as kin who would resemble each other.[25]

The gods are centered, or located slightly above the center.[21] The six male gods are dressed in an overcoat, often with long cords of cloth—symbols of military command in traditional Korean attire—hanging from their waist or chest,[26] and are seated in lotus position.[27] The goddesses wear a skirt and a long upper garment tucked under it,[28] and either bare their breasts[22] or have marks on their robes over their breasts.[29] Three of the four goddesses take an unnatural position in which the shape of the skirt suggests that they are seating while the legs under them suggest that they are standing.[30] All deities wear ribbon-like scarves on their necks almost unattested in the history of Korean clothing; similar pieces of clothing are known only from the late first millennium. Golden bracelets often adorn their wrists.[31] All but two of the gods hold fans: two folding fans and the rest non-folding ones.[27] All gods have red dots on their faces. The gods hung in the north and those hung in the west would have appeared to be looking at each other when hung, except for Jajihong'i-agissi, who looks away towards the south.[22]

The names of the gods as given by the paintings correspond to a specific element within the full names given by the bon-puri.[12] They are written in red in Chinese characters, in upper left for the northern portraits and in upper right for the western ones.[22] All names are given in three characters with the final character being 位 wi "seat", so that the painting of the god Surang-sangtaeja-manora "Lord High Prince of the Spirit of Water" is simply titled 水靈位 Suryeong-wi "Seat of the Spirit of Water".[12]

Male deities[edit]

Jeseok-cheonwang-manora, whose name is given as Jeseok in the painting, is dressed like a Buddhist priest.[27] He wears a transparent conical hat associated with Korean Buddhist monks,[32] but the red orb on top, reminiscent of the sun, is unknown in monks' garb.[28] He has a red kasaya over a yellow overcoat, although actual Korean monks wear gray.[33] The god holds a white fan, and a lacquered bamboo staff (not used by Korean monks) with a red-beaked crow perched on it.[23][27] His stance with the staff is suggestive of a warrior holding a spear.[23] Cloud and chrysanthemum motifs[a][27] are drawn on the fringes of Jeseok's overcoat; dancheong patterns on the pink cloth that flutters around him; and diagonally positioned rectangles on his red kasaya.[32]

Eomora Wonmang-nim (Wonmang in the painting) wears a black gat hat over a headband, and a green overcoat with red and blue fringes,[35] probably cheollik: the traditional coat of Korean military commanders.[33] The coat has cloud and chrysanthemum motifs.[27][35] His shoes are black wooden ones, which were traditionally worn at the Korean court.[33] The god holds a lacquered folding fan in one hand—unusual in Korean folding fans, which are painted but not lacquered[23]—and extends his other hand as if making a command.[36]

Surang-sangtaeja-manora (Suryeong in the painting) has either a wonyu-gwan headdress, worn by kings and crown princes when greeting the court, or a geumnyang-gwan headdress, worn by the highest-ranking ministers.[33] Like Wonmang, he wears a green overcoat with red and blue fringes and cloud and chrysanthemum motifs,[27][35] as well as black wooden shoes, and holds another lacquered folding fan.[37] However, the god's headdress cannot be worn together with such an overcoat in Korean court protocol,[28] nor does he wear the necessary belt.[33] Suryeong's face is childlike, despite the beard.[38]

Naeoe-cheonjado-manora (Cheonja in the painting) wears a black gat hat over a headband, red cheollik with green fringes and chrysanthemum motifs,[27][39] and black wooden shoes.[33] He holds a staff or a sword in one hand, but no fan.[38] Snakes with blue rings, or cloth representing such snakes, coil behind his head.[33][38]

Gamchal-jiban'gwan-han-jip-manora (Gamchal in the painting) wears a form of futou, an East Asian official's black headdress; a green overcoat with red and blue fringes, chrysanthemum motifs,[27][40] and wide sleeves;[33] and a pair of unhye, leather shoes with cloud motifs typically worn by noblewomen.[38] As with Suryeong, the headdress of Gamchal is not normally compatible with his overcoat.[28] This god's hands are empty.[38]

Sangsa-daewang (Sangsa in the painting) wears a very unusual turban-like headdress surrounding a white and red disc that may reflect the god's origins in the Western Regions of Central Asia.[41] Alternately, it may be a stylized form of the felt hat traditionally worn by Korean officers.[38] The red overcoat with green fringes is marked by chrysanthemum motifs in the inside and swirling cloud motifs on the fringes.[40] Sangsa holds a white or yellow[27] fan and wears black wooden shoes.[33]

-

Jeseok

-

Wonmang

-

Suryeong

-

Cheonja

-

Gamchal

-

Sangsa

Female deities[edit]

Bon'gung-jeon (Bon'gung in the painting) wears a jokduri coronet with jade beads[4] over a chignon fixed by a hairpin in the shape of a bird.[26] She has a fan in her left hand that she holds near her breasts. Unlike the other goddesses, her free hand is pointing rather than open, giving her an authoritative air.[4] She wears a green upper garment and a red skirt, both with swirling cloud motifs.[42] Her skirt is tied by a waistband to which two cords are connected. The waistband and cloth are normally white in actual Korean dress, but the goddess's are green and blue. She is the only goddess in lotus position.[26][27]

Jungjeon-daebuin (Jungjeon in the painting) wears a jokduri from which beads and a bottle of liquor hang.[38] She holds a fan in one hand, and wears a red upper garment with swirling cloud motifs, a green skirt with regularly arranged chrysanthemum motifs, a white waistband and cords, and unhye shoes.[26][27]

Jeongjeol-sanggunnong (Sanggun in the painting) also wears a chignon[26] studded with beads, fixed by a bird-shaped hairpin.[38] She holds a fan in one hand. Both her green upper garment and her red skirt are dotted with chrysanthemum motifs arranged in lines.[43] Her waistband is red and she wears unhye shoes.[26][27]

Jajihong'i-agissi (Hong'a in the painting) has her hair loose and not in a chignon. This hairstyle is characteristic of unmarried women.[26] She too has a bird-shaped hairpin and beads in her hair, although the latter are scattered about.[44] Uniquely, she wears a yellow upper garment[26] tucked under a red skirt, with cloud motifs on both.[44] Among the six non-folding fans of the gods, only hers is red. She wears a white waistband with green cords, and unhye shoes.[26][27]

-

Bon'gung

-

Jungjeon

-

Sanggun

-

Hong'a

Recorded history[edit]

The Naewat-dang shrine was one of the four shamanic temples on the island that were recognized by the Joseon state,[45] and there is some circumstantial evidence that the shrine might have been quite ancient.[46] Historically, the shrine was particularly associated with conception and fertility. A couple who desired children would have a shaman select an auspicious day for them, then visit Naewat-dang and make sacrifices to its gods. Once the rituals were completed and the shaman departed, the couple would have sex within the shrine in order to conceive the hoped-for child.[47]

Naewat-dang first appears in recorded history in a Joseon Veritable Records entry for 1466, during the reign of Sejo.[3] That year, a man accused a local official of offering sacrifices at Naewat-dang before a portrait of Danjong, the teenage king who had been usurped and murdered in 1455 by his uncle Sejo. It was soon discovered that the claim was slanderous. The king ordered the rituals at Naewat-dang to be resumed, although some portraits at Naewat-dang had already been burnt due to the affair.[48] This entry demonstrates that the shrine already housed portraits of some sort before 1466.[49] Hyun Yong-jun, one of the most important scholars of Jeju shamanism,[50] considers it almost certain that the two currently missing portraits were the ones destroyed in 1466, presumably because the gods that they depicted resembled Danjong.[51]

In 1702, Yi Hyeong-sang, a zealous Confucian magistrate of Jeju, endeavored to uproot the shamanic religion entirely. This involved the destruction of 129 shrines and the burning of all ritual artefacts. It is not known whether the Naewat-dang paintings survived this event,[52] although Hyun suggests that they probably did, as a post-1702 restoration project would logically have repainted portraits of all twelve gods and not just ten.[53] In any case, Yi Hyeong-sang was fired only a year later and replaced by a magistrate supportive of shamanism. If the Naewat-dang paintings were destroyed by Yi, they were likely quickly restored based on the lost originals.[52]

Naewat-dang was demolished for good in 1882,[47] but the paintings survived because Go Im-saeng, the shaman who was in charge of the shrine, took them to his own house. When Go died, his wife was forced to sell the house and live homeless in a cave. She took the paintings with her. The Jeju National University professor Hyun Yong-jun fortuitously encountered the woman in 1959, when she was already nearly eighty years old. When she died in 1963, Hyun took the paintings away from the cave to be safely preserved at his university, where they remain today.[54] In 2001, the South Korean Cultural Heritage Administration designated them as an Important Folklore Cultural Property.[55]

Date of composition[edit]

As no scientific analysis of the paper has yet been conducted, the date when the portraits were painted remains unknown.[56] Attempts to estimate the rough date of creation have focused on stylistic elements, which suggest that they were painted during or before the 17th century.[57]

According to the Goguryeo murals of the mid-first millennium CE, the upper garments of Korean women were long enough to reach the buttocks. The garments of the 17th century had shortened somewhat, but were still long enough to reach the waist. They became progressively shorter over the next two centuries. By the 19th century, the Korean woman's upper garment was 25 centimeters (10 inches) long on average and could not fully cover the breasts.[58] The goddesses' upper garments in the Naewat-dang paintings are about as long as those in 17th-century paintings of Korean women, and are far longer than 18th- or 19th-century equivalents.[59] Meanwhile, the portraits depict the upper garments as being tucked under the skirt, a practice unusual in the Goryeo era (936–1392) and afterwards but popular in Later Silla (676–936) fashion. The form of the skirts is also similar to those worn until the early Goryeo. There may be inconsistencies in the time-frames of the deities' robes.[60]

-

Naewat-dang painting

-

19th-century painting

Headgear is also a potential indicator of the time period. Over the course of the second millennium, the two boards on the side of Korean futou headdress became increasingly thicker, growing horizontally shorter and vertically wider. The futou boards in the Naewat-dang portrait of Gamchal are not as thin as the boards of the Goryeo period, but are thinner than mid-Joseon versions from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.[57] The goddesses' chignons also resemble Goryeo women's hairstyles, although the position of the hairpin is inaccurate.[23]

-

Naewat-dang painting

Characteristics and symbolism[edit]

The Naewat-dang paintings are highly unlike mainland shamanic paintings in iconography, facial expressions, and symbolism, to the point that a curator hired by the Cultural Heritage Administration did not think that they were traditional Korean works at all.[61] They feature a sense of movement unknown in the mainland, especially in the fluttering of the male gods' overcoats. This may be connected to the Jeju belief that the descent of the gods into the human world is accompanied by winds[13] and further reflect the dynamism of the divine characters in Jeju village-shrine myths.[62]

Unlike the mainland paintings, the Naewat-dang gods are inhuman and grotesque.[63] The posture of the goddesses is unnatural.[30] The gods' hands resemble the wings of birds, dragons' claws,[64] or the gnarled roots and branches of the paengnamu tree (Chinese hackberry), the abode of village gods in Jeju religion.[65] The shapes and folds of their robes are also reminiscent of rocks and shellfish[66] and hint at the strangeness of the bodies that the gods must have under them.[30] There may be a connection to tree-human hybrid deities that feature in other village-shrine myths,[67] such as the goddess described below:

Her body is torn in the thorn bushes and all her skin is shed. She has become a tree and moss has sprouted on her, but she stays as a human in her hands and feet... The eyes are the eyes of a human, the body has become a tree.[68]

The cords of cloth that hang from the Naewat-dang deities are reminiscent of snakes, which are sacred patrons of wealth and a favored manifestation of village gods in Jeju religion.[69][29] The eyes of the gods are also serpentine, while there are ringed snakes or snake-like cords behind Cheonja's hat.[29] At the same time, there is also bird symbolism in the hands, in the goddesses' headpins, and in the red-beaked crow on Jeseok's staff.[64][70] This is unusual, as snakes and birds are incompatible in conventional Korean iconography.[64] The red-beaked crow may be linked to an episode in the Chasa bon-puri myth in which the god of death transforms into a bird and perches on a bamboo pole to escape the hero Gangnim.[27]

Fans, which eight of the gods carry, are among the most important shamanic ritual implements in mainland Korea. Peculiarly, they are not used in modern Jeju ritual.[71] The non-folding fans have very long handles that suggest that they were used for rituals and not to make wind. Such fans are unknown in other shamanic paintings.[23] The bottles that hang from the jokduri may be connected to fertility or shamanic ritual.[34][38] The exposed breasts of the goddesses also testify to Naewat-dang's purpose as a fertility shrine.[34]

Explanatory notes[edit]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b Kendall et al. 2015, p. 19.

- ^ Kendall et al. 2015, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d Kim Y. 1997, p. 194.

- ^ a b c Kim Y. 1997, p. 209.

- ^ Kendall et al. 2015, p. 36.

- ^ Kim Y. 1997, pp. 194, 209.

- ^ Kim Y. 1997, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Kim Y. 1997, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Kang S. 2006, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Kim Y. 1997, pp. 189–190.

- ^ Jeon J. 2013, pp. 271–272, 277.

- ^ a b c d Kim Y. 1997, p. 193.

- ^ a b c Jeon J. 2013, pp. 272–273.

- ^ Hyun Y., Ha H. & Lee S. 2001, p. 18.

- ^ a b Jeon J. 2013, p. 274.

- ^ Jeon J. 2013, p. 269.

- ^ Jeon J. 2013, pp. 274–275.

- ^ Jeon J. 2013, p. 275.

- ^ Jeon J. 2013, p. 277.

- ^ a b Hyun Y., Ha H. & Lee S. 2001, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Kang Y. & Park Y. 2015, pp. 64–69.

- ^ a b c d Kang Y. & Park Y. 2015, p. 69.

- ^ a b c d e f Hyun Y., Ha H. & Lee S. 2001, p. 22.

- ^ Hyun Y., Ha H. & Lee S. 2001, p. 24.

- ^ Jeon J. 2013, pp. 269–270.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hyun Y., Ha H. & Lee S. 2001, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Kim Y. 1997, p. 207.

- ^ a b c d Hyun Y., Ha H. & Lee S. 2001, p. 21.

- ^ a b c Jeon J. 2013, p. 271.

- ^ a b c Jeon J. 2013, p. 270.

- ^ Hyun Y., Ha H. & Lee S. 2001, pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b Kang Y. & Park Y. 2015, p. 64.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hyun Y., Ha H. & Lee S. 2001, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Kang Y. & Park Y. 2015, p. 70.

- ^ a b c Kang Y. & Park Y. 2015, p. 65.

- ^ Kim Y. 1997, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Hyun Y., Ha H. & Lee S. 2001, pp. 13, 22.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kim Y. 1997, p. 208.

- ^ Kang Y. & Park Y. 2015, p. 66.

- ^ a b Kang Y. & Park Y. 2015, p. 67.

- ^ Hyun Y., Ha H. & Lee S. 2001, p. 14, 26.

- ^ Kang Y. & Park Y. 2015, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Kang Y. & Park Y. 2015, p. 68.

- ^ a b Kang Y. & Park Y. 2015, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Hyun Y., Ha H. & Lee S. 2001, p. 27.

- ^ Hyun Y., Ha H. & Lee S. 2001, pp. 8–10.

- ^ a b Hyun Y., Ha H. & Lee S. 2001, p. 10.

- ^ Hyun Y., Ha H. & Lee S. 2001, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Hyun Y., Ha H. & Lee S. 2001, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Kang S. 2018, p. 164.

- ^ Hyun Y., Ha H. & Lee S. 2001, pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b Kim Y. 1997, p. 197.

- ^ Hyun Y., Ha H. & Lee S. 2001, p. 20.

- ^ Hyun Y., Ha H. & Lee S. 2001, pp. 5–6.

- ^ "Jeju-do Naewat-dang musindo" 제주도 내왓당 무신도 (濟州道 내왓堂 巫神圖) [Shamanic paintings of Naewat-dang, Jeju Province]. heritage.go.kr. Cultural Heritage Administration. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ Hyun Y., Ha H. & Lee S. 2001, p. 25.

- ^ a b Hyun Y., Ha H. & Lee S. 2001, p. 16.

- ^ Hyun Y., Ha H. & Lee S. 2001, p. 15.

- ^ Hyun Y., Ha H. & Lee S. 2001, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Hyun Y., Ha H. & Lee S. 2001, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Hyun Y., Ha H. & Lee S. 2001, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Jeon J. 2013, p. 287.

- ^ Jeon J. 2013, p. 288.

- ^ a b c Hyun Y., Ha H. & Lee S. 2001, p. 23.

- ^ Jeon J. 2013, pp. 270, 282.

- ^ Jeon J. 2013, pp. 291–292.

- ^ Jeon J. 2013, p. 290.

- ^ 몸동인 가시자왈에 훑어 만딱 허물이요, 남이 뒈여 늣이 돋고 손광 발은 사름이 뒈여 잇어지니... 눈은 사름의 눈이요, 몸은 나미가 뒌 게 이시니 Jeon J. 2013, p. 290

- ^ Kim Y. 1997, p. 206.

- ^ Kim Y. 1997, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Kim Y. 1997, p. 205.

Works cited[edit]

- 강소전 (Kang So-jeon) (2006). "Jeju-do gut-ui mugu 'gime'-e daehan gochal" 제주도 굿의 무구(巫具) ‘기메’에 대한 고찰 [Study on the gime, ritual implements of Jeju shamanism]. Han'guk Musokhak. 13: 103–141. ISSN 1738-1614. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ————————— (2018). "Jeju-do muga musok yeon'gu-ui seonggwa-wa gwaje" 제주도 무가·무속 연구의 성과와 과제 [Accomplishments and tasks of Jeju shamanism studies]. Jeju-do Yeon'gu. 50: 1–43. ISSN 1229-7569. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- 강연심 (Kang Younsim); 박영원 (Park Youngwon) (2015). "Jeju Naewat-dang musindo sip sinwi dijain hyeongtae bunseok" 제주 내왓당 무신도 10신위 디자인 형태 분석 [Analysis of the design styles of the ten shamanic portraits of Naewat-dang, Jeju] (PDF). Han'guk Kontencheu Hakhoe Nonmunji. 15 (9): 61–71. doi:10.5392/JKCA.2015.15.09.061. ISSN 1598-4877. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- 김유정 (Kim Yu-jeong) (1997). "Jeju-ui musindo: Hyeonjon-haneun Naewat-dang musindo sip sinwai yeon'gu" 제주의 무신도—현존하는 내왓당 무신도 10신위 연구— [Shamanic paintings of Jeju: A study of the ten surviving portraits of the shamanic paintings of Naewat-dang]. Tamna Munhwa. 18: 183–214. ISSN 1226-5306. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- 전주희 (Jeon Juhee) (2013). "Naewat-dang musindo-ui dosangseong-gwa Jeju musok-ui saengtaeseong" <내왓당무신도>의 도상성과 제주 무속의 생태성 [The iconicity of the Naewat-dang shamanic paintings and the ecology of Jeju shamanism]. Han'guk Musokhak. 26: 261–297. ISSN 1738-1614. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- 현용준 (Hyun Yong-jun); 하효길 (Ha Hyo-gil); 이수자 (Lee Soo-ja) (2001). Jeju-do Naewat-dang musindo 제주도 내왓당 무신도 [Shamanic paintings of Naewat-dang, Jeju Province] (Report). Cultural Heritage Administration. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- Laurel, Kendall; Yang, Chong-sŭng; Yang, Jongsung; Yoon, Yul-soo; Yun, Yŏl-su (2015). God Pictures in Korean Contexts: The Ownership and Meaning of Shaman Paintings. University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 9780824847630. Retrieved July 11, 2020.