Norbert Vesak

Norbert Vesak | |

|---|---|

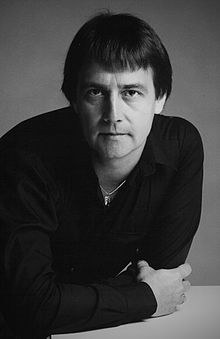

Norbert Vesak, 1983 | |

| Born | Norbert Franklin Vesak October 22, 1936 Port Moody, British Columbia, Canada |

| Died | October 2, 1990 (aged 53) |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Occupation(s) | Choreographer, Dancer, Master Teacher, Theatrical Director, Opera Ballet Director for the San Francisco Opera and the Metropolitan Opera |

| Years active | 1959-1990 |

| Notable work | The Ecstasy of Rita Joe, What To Do Till the Messiah Comes, In Quest of the Sun, Meadow Dances, Death in Venice, Carmen, Sacre du Printemps, Midsummer Night's Dream, Sibelius Songs, Veder Engel Nach Unserer Mensch, Elegie Für Eine Tote Liebe, Whispers of Darkness, The Grey Goose of Silence, Pieces of Glass, Belong Pas de Deux, The Medium, Whisper of Night |

| Partner | Robert de La Rose |

| Awards | Winner of Two Gold Medals 1980 for Outstanding Choreography, International Concours at Osaka, Japan and Varna, Bulgaria |

Norbert Vesak (October 22, 1936 – October 2, 1990), one of Canada's leading choreographers in the 1970s, was a ballet dancer, choreographer, theatrical director, master teacher, dance columnist,[1] lecturer,[2] and opera ballet director, known for his unique, flamboyant style[3] and his multimedia approach to classical and contemporary choreography.[4][5] He is credited with helping to bring modern dance to Western Canada.[6][7][8]

Biography[edit]

Although Vesak worked internationally as a choreographer, he was frequently referred to as "Canada's finest male dancer."[9] Early in his career, he often choreographed works and then danced in them as well, receiving critical acclaim for both roles.[10] He was described as a "Renaissance Man", well known as a lecturer, dancer, set and costume designer, and teacher, as well as for his choreography and work in the theater.[11] Vesak was born in Port Moody, British Columbia in 1936 to Frank and Nora Vesak, of Czech and Belgian descent.[12] As a child, he was an opera fan who described listening to Metropolitan Opera broadcasts.[13] He studied dance in Edmonton, Alberta with Laine Metz and followed that with study under Josephine Slater, whom he described as having the greatest influence on his career at that time, because in addition to teaching and mentoring him, she introduced him to Ted Shawn who was one of the pioneers of modern dance in the United States.[14] Vesak was given a scholarship to train with Shawn at Jacob's Pillow in Lee, Massachusetts, where he trained and eventually joined the teaching staff.[15] Vesak also studied under Margaret Craske, Merce Cunningham, Geoffrey Holder, Pauline Koner, Madam La Meri, Robert Abramson, Ruth St. Denis, and Vera Volkova, among others.[16] He was classically trained, and was a member of the Royal Academy of Dancing and Ballet in Britain and also studied ethnic dance extensively.[17] Although he wanted to be an actor, at the age of 17, he decided on dance[11] and was awarded a scholarship in 1960 to Jacob's Pillow Dance in Massachusetts, where he studied under the direction of Ted Shawn and other well-known teachers.[18] When Vesak returned to Vancouver, he co-founded the Pacific Dance Theatre in 1964 and later founded the eponymous Norbert Vesak Dancers, which became the Western Dance Theatre in 1970.[19]

In 1964, Norbert Vesak was named resident choreographer for the Vancouver Playhouse Theater.[20] He went to England to perform with Western Theatre Ballet, and then returned to Canada.[21] During the 1960s, he served as the resident choreographer for the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra, Theatre Calgary and the Banff Festival Ballet, and several other companies, doing choreography, teaching, and directorial work.[22]

By the time he founded the Western Dance Theatre, he had already created 60 major works and had been a guest choreographer at several companies.[23] His work with the Western Dance Theater was, by his description, designed to present stories about human relations, with influences from the monumental geography of British Columbia: "We would hope the rugged beauty of the environment of B.C. was evident in Western Dance Theatre's work, and that it is truly a product of a unique area of Canadian topography."[24] Vesak often undertook large, complex projects that attracted critical admiration for their scope, as for example, in June, 1969, when he choreographed Pierrot Lunaire by Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg, danced to the central part of Schoenberg's 21-part orchestration of poems by Belgian poet Albert Giraud.[25] One of Vesak's major objectives was educating the public about contemporary dance, and his companies often presented free educational programs on contemporary dance in public schools and other public venues.[26][27] His dance school in Vancouver at one time had an enrollment of more than 700 students.[11]

From 1961 to 1962, he published what has been called the "shortest-lived dance magazine in Canadian history".[28] Called "The Canadian Dance World Magazine", Vesak and Slater published a total of six issues of the free 16-page magazine and distributed it to 300 individuals who were interested in dance. Each issue had its own theme including: men in dance, ethnic dance, religion in dance, symbolism, and leaders of the modern dance movement.[29] He described the magazine as being "dedicated to the furtherance of dance" in Canada and he published it without attribution.[30] Known for choreographing both classical and contemporary work, in 1963, Vesak debuted his choreographic work entitled Parenthesis, at the first Canadian Modern Dance Festival in Toronto.[31] He also created works, such as From Ecstasy to Despair in 1969, that were described as futuristic and emotionally jarring, that provided an important social message.[32] He was director of the San Francisco Opera ballet from 1970 to 1975. He was named official choreographer for the Royal Winnipeg Ballet in 1975.[33] Also in 1975, he was named director of the Metropolitan Opera ballet.[34] He became one of the most internationally renowned choreographers of his time, having the rare distinction of being awarded two international gold medals for choreography in a single year, with his broad range of work performed throughout the United States, Canada, Europe, and South America.[35]

Two notable ballets Vesak created in the 1970s, The Ecstasy of Rita Joe and What To Do 'Till the Messiah Comes, were major successes for the Royal Winnipeg Ballet and highlighted important cultural and sociological issues.[36] The Ecstasy of Rita Joe, was commissioned by the Manitoba Indian Brotherhood and debuted as a ballet in 1971.[37] The ballet was based on a controversial play written by George Ryga about a young Aboriginal girl who leaves the reservation to move to the big city, and about the cultural conflicts, poverty, and violence that she experiences.[38] Vesak's ballet was said to surpass the play itself in terms of delivering the intended message to the audience: "Most of the reviews were vehement in their support of the ballet's antiracist message. William Littler in the Toronto Daily Star called it 'perhaps the ballet of 1971, in terms of its social importance to Canadians'. He noted that the ballet is 'less angry, less polemical in tone than Ryga's play, which hammers away at the idea that white justice cannot comprehend the Indian fact.' In 'the abstracting medium of dance,' wrote Littler, the message 'loses some of its soap-box shrillness and gains symbolic power.'"[39] The commissioning of this work by the Manitoba Indian Brotherhood was said to have been a calculated effort by the Brotherhood to bring the message about the effects of racism against indigenous peoples to a larger population through use of a medium, ballet, that was not usually used for inspiring societal understanding.[40] "As a platform for Aboriginal rights, The Ecstasy of Rita Joe was undeniably potent, with people sobbing at the end of the ballet."[41]

The ballet met with equal success when it was performed internationally: “Themes explored in Norbert Vesak’s the Ecstasy of Rita Joe met with resounding acceptance throughout Australia on the spring tour of 1972. Anna Maria de Gorriz, in the title role, brought down the house with curtain calls in Sidney and Melbourne.”[42]

In 1973, What to do Till the Messiah Comes became another of Vesak's most acclaimed works, described as a visionary ballet set to rock music,[43] and in 1980, he won gold medals for his choreography of Belong Pas de Deux from that work at the International Ballet Concours in both Varna, Bulgaria and Osaka, Japan.[2] In addition, Canadian ballerina Evelyn Hart won a gold medal in Varna, Bulgaria for her performance of Belong with David Peregrine in 1980.[2] Hart rose to international stardom, and Vesak's "Belong" became a signature piece for her.[44] Belong Pas de Deux remains one of Vesak's most enduring works, and is in the repertoires of ballet companies worldwide.[45] Performances of it were televised in several countries including Canada, the United States, Scotland, England, Germany, and Israel, and it became the title subject of an IMAX film entitled Heart Land, which was released in 1987 and distributed internationally.[46][47][48] In 1989, Norbert Vesak collaborated with director Franco Zeffirelli, choreographing La Traviata for the Metropolitan Opera.[49]

In addition to his choreography work, Norbert Vesak was highly sought after for his skill as a Master Teacher, particularly regarded for the individual attention he gave to dancers.[50] He often co-taught master classes with Joffrey Ballet founder Robert Joffrey.[51] Vesak's commitment to mentoring and providing dance opportunities to young dancers, as well as raising interest in dance, was clear throughout his life.

Vesak was regularly chosen to create new works for international companies, receiving commissions from such institutions as the Metropolitan Opera, the Berlin Ballet, the North Carolina Dance Theatre, the Los Angeles Ballet, the Miami Ballet, the Scottish Ballet, the Joffrey II Dancers, Bayerische Staatsoper in Munich, the National Ballet of Canada, the Winnipeg Contemporary Dancers, The Alberta Ballet, Ballet Florida in Palm Beach, National Association for Regional Ballet, the Marin Ballet in San Rafael, California, and the Deutsche Opera Ballet in Berlin, in addition to many others.[52]

Personal[edit]

Norbert Vesak's long-time partner and creative collaborator was Robert de La Rose, a costume and set designer who worked on Vesak's productions and was involved in the concept development of many of Vesak's works.[53][54]

Lady of the Camellias[edit]

Lady of the Camellias was conceived by Norbert Vesak and Robert de La Rose to be a full-length ballet based on the novel of the same name by Alexander Dumas.[55] Although Vesak worked on the concept, the libretto, selected the music, and even had the costumes designed by de La Rose, Lady of the Camellias was ultimately choreographed by another international choreographer, Val Caniparoli.[56] Vesak died suddenly of a brain aneurysm while on his way to attend the 20th anniversary celebration of North Carolina Dance Theater, where a work that he had designed for that company in 1975, The Gray Goose of Silence, was being performed to commemorate the occasion.[57] After his death, Lady of the Camellias remained in limbo for three years until de La Rose approached Caniparoli about taking it on.[58] Caniparoli had known Vesak well, since Vesak had given Caniparoli his first professional job and was also one of Caniparoli's teachers.[59] Caniparoli agreed to do the project, adapting Vesak's concept and music to his own choreography, with de La Rose providing the costume and partial set design.[60] It was Caniparoli's first full-length work, and debuted by Ballet Florida in 1994.[61] It has since been performed by many companies including: Ballet West, Ballet Florida, Boston Ballet, Cincinnati Ballet, Tulsa Ballet, Alberta Ballet, Diablo Ballet, and Royal Winnipeg Ballet.[62][63]

Quotes[edit]

"A trained artist can extemporize, but training comes first. You have to be a master of your physical inadequacies, and the only way to do so is to study. No one is born with a dancer's body."[64]

Awards[edit]

- Gold Medal for Choreography, Tokyo World Ballet Concours (1980)[65]

- Gold Medal for Choreography, International Ballet Festival, Varna, Bulgaria (1980)[66]

Choreographed works[edit]

- Family Portrait (Pacific Dance Theatre)

- Springhill '58 (Pacific Dance Theatre)

- Cainsmorning (Western Dance Theatre)

- The Land Before Time (Playhouse Theatre)

- Chichester Psalms (Western Dance Theatre)

- Concierto (Western Dance Theatre)

- Pearl White Moments (Western Dance Theatre)

- Home Sweet Home (Western Dance Theatre)

- Turangalila (Western Dance Theatre)[67]

- Pierrot Lunaire (Norbert Vesak Dance Studio)[68]

- The Ecstasy of Rita Joe (Royal Winnipeg Ballet)

- What To Do Till the Messiah Comes (Royal Winnipeg Ballet)

- Belong Pas de Deux (Royal Winnipeg Ballet)

- A Midsummer Night's Dream (North Carolina Dance Theater)

- Carmen (Santa Barbara Ballet)

- Nutcracker (Marin Civic Ballet)

- Grass and Wild Strawberries (Playhouse Theatre)

- When We Are Kings (Banff Festival Ballet)[69]

- Don Giovanni (Directed by Franco Zeffirelli) Metropolitan Opera

- Blue Is the Color of My True Love's Bag (Playhouse Theatre)

- Once for the Birth Of... (Playhouse Theatre)

- Esclarmonde Performed at San Francisco Opera, Metropolitan Opera

- First Century Garden Performed at Canada's Contemporary Dancers

- Fruhlingstimmen (Music: Johann Strauss Sr. and Jr.) (Commissioned for the International Garden Festival, Munich)

- Mass (Directed and Choreographed) West Coast Premiere, Music by Leonard Bernstein Set design: Ming Cho Lee Performed at: University of California, Berkeley

- The Gift to Be Simple (Western Dance Theatre, Vancouver)

- Pas de Deux (Nice Opera, France)

- Pas de Deux (L'Opera Paris)

- Die Fledermaus Variations (Metropolitan Opera Ensemble)

- Stravinsky Dances (Music: Igor Stravinsky) (International Ballet Competition, Helsinki)

- Table Manners (Joanna Berman, San Francisco Ballet)

- Tchaikowsky Dances (Dancers: Cynthia Gregory and Fernando Bujones) (New World Ballet)

- The Rite of Spring (New World Ballet) Debut: Galena Panoff & Anthony Dowel

- Meadow Dances (Dancers: Evelyn Hart and David Peregrine) (Royal Winnipeg Ballet)

- Threepenny Dances (Music: Kurt Weill) (New Jersey Ballet)

- The Gershwin Song Book, Music: George Gershwin, Costumes and sets: Robert de La Rose, Performed at Les Ballets Jazz de Montreal

- In Quest of the Sun (Greg Martindale Debut: Royal Winnipeg Ballet, 1975)

- Babar, Music: Francis Poulenc, Debut: The Breakers, Newport, RI (1978) and played at the White House (1979)

Filmography[edit]

- The Ecstasy of Rita Joe (CBC series Musicamera) (1974)

- The Metropolitan Opera Presents: 'Rigoletto' (1977)

- The Metropolitan Opera Presents: 'Rigoletto' (1981)

- Heart Land IMAX Film featuring Belong Pas de Deux

- Collaboration with Industrial Light and Magic to produce special effects for Clara's Dream (1987)

- Evelyn Hart's Moscow Gala, Produced by Triune Films for Canadian Broadcasting System (1987)

- "To Be A Dancer" (Film Project with Bruce Nicholson, Lucasfilm)

Opera Choreography[edit]

- 1969 Faust (Vancouver Opera Association)[70]

- 1972 L'Africaine (San Francisco Opera)

- 1972 Le Nozze di Figaro (San Francisco Opera)

- 1973 Boris Godunov (San Francisco Opera)

- 1973 Die Fledermaus (San Francisco Opera)

- 1973 La Favorita (San Francisco Opera)

- 1973 Rigoletto (San Francisco Opera)

- 1973 Tannhäuser (San Francisco Opera)

- 1973 La Grande Duchesse de Gérolstein (San Francisco Opera)

- 1974 Esclarmonde (San Francisco Opera)

- 1977 Tannhauser (Metropolitan Opera) (Also performed in 1978, 1982, 1984, 1987)

- 1979 La Gioconda (Metropolitan Opera)

- 1980 La Traviata (San Francisco Opera)

- 1982 Sagracao Do Primavera (Music: Igor Stravinsky) (Ballet Teatro Municipal Do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil)

- 1982 Mephistofeles (Greater Miami Opera)

- 1983 Lied Des Windes (Bavarian State Opera House, Munich)

- 1983 Tango Finale (Bavarian State Opera House, Munich)

- 1984 Sacre du Printemps (Bavarian State Opera House, Munich)

- 1984 Samson & Delilah (Florentine Opera)

- 1984 Graduation Ball (Bavarian State Opera, Munich)

- 1984 Silent Promises (Bavarian State Opera, Munich)

- 1985 Elegie Fur Eine Tote Liebe (Birgit Keil, Stuttgart Ballet)

- 1985 Pieces of Glass (Music: Philip Glass) (Stuttgart Ballet)

- 1986 Der Tod in Venedig (Bavarian State Opera Ballet, Munich)

- 1986 The Dance Alphabet (Bavarian State Opera House, Munich)

- 1986 Kinder Sinfonie (Bavarian State Opera House, Munich)

- 1990 Don Giovanni (Metropolitan Opera) (Also performed in 1991, 1994, 1995, 1997)

Theatrical and Opera Direction[edit]

- Carmen (Greater Miami Opera)

- Trouble in Tahiti (Leonard Bernstein)

- Mass (Leonard Bernstein)

- Samson & Dalila (Camille Saint-Saëns)

- The Medium (Gian Carlo Menotti)

- Carmen (Georges Bizet) (New Orleans Grand Opera)

- Babar: The Little Elephant (Francis Poulenc)

- The Merry Widow (Greater Miami Opera, 1981)[71]

External links[edit]

- Norbert Vesak at The Canadian Encyclopedia

- Metropolitan Opera

References[edit]

- ^ Sunter, Robert. "Vesak Seeks Craft First". Vancouver Sun.

- ^ a b c "Second Gold Medal For Choreographer". San Francisco Chronicle. July 24, 1980.

- ^ Wyman, Max (December 22, 1969). "The Happiness Dancers: Vancouver's New Modern Troupe Is Previewed". The Vancouver Sun.

- ^ Pepper, Kaija (2012). Renegade Bodies: Canadian Dance in the 1970s. Dance Collection Danse Press, 2012. ISBN 978-0929003702.

- ^ Anderson, Jack (October 3, 1990). "Norbert Vesak, 53, Former Chief of the Met Opera Ballet, Is Dead". The New York Times.

- ^ Rubin, Don (2000-09-21). World Encyclopedia of Contemporary Theater: The Americas. Routledge. p. 123. ISBN 978-0415227452.

- ^ Wyman, Max (May 26, 1970). "Western Dance Theatre leaps into reality". Vancouver Sun.

- ^ MacGillivray, Alex (May 27, 1966). "Leisure". Vancouver Sun.

- ^ Hunter, Don (January 9, 1970). "A new company is born". Vancouver Sun.

- ^ Hunter, Don (December 22, 1969). "Vesak preview exciting event". Province Paper.

- ^ a b c MacDermid, Cassandre (March 26, 1970). "Norbert Vesak Wins Friends For Contemporary Dance". Trail Daily Times.

- ^ Lingg, Ann (January 1, 1977). "The House". The Metropolitan Mirror.

- ^ Robinson, Francis (1957). The Metropolitan Opera. New York: Doubleday and Company. p. 189. ISBN 0-385-12975-0.

- ^ Wyman, Max. "Canada's Happiness Dancers". Dance Canada Danse Norbert Vesak Archives.

- ^ "Dance Collection Danse Archives".

- ^ Anderson, Jack (October 5, 1990). "Norbert Vesak, 53, Former Chief of the Met Opera Ballet, Is Dead". The New York Times.

- ^ Hunter, Don (January 9, 1970). "Dance: A new company is born". Vancouver Sun.

- ^ Hunter, DON (January 9, 1970). "A new company is born". Vancouver Sun.

- ^ "Artists Biography: Norbert Vesak". ArtsAlive.ca. Dance National Arts Center. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- ^ "Cameron Academy". Archived from the original on August 21, 2013. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- ^ "Meet the Artists: Norbert Vesak". ArtsAlive.co. Retrieved May 12, 2013.

- ^ "Meet the Artists: Norbert Vesak". ArtsAlive.ca. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- ^ Hunter, Don (January 9, 1970). "A new company is born". Vancouver Sun.

- ^ Wyman, Max (November 7, 1970). "City enriched by two dance companies". Vancouver Sun.

- ^ Wyman, Max (June 25, 1969). "Virtuosity Amidst Quantity". Vancouver Sun.

- ^ "Vesak's Great Promise: A big dance step". Vancouver Express. April 30, 1970.

- ^ Wyman, Max (November 29, 1968). "Letting the Kids Tell It All". Vancouver Sun.

- ^ Bowring, Amy (May 2008). "Marking Time". The Dance Current. 11 (1): 14.

- ^ Bowring, Amy (May 2008). "Marking Time". The Dance Current. 11 (1): 14.

- ^ Vesak, Norbert (1961). "Dear Reader". The Canadian Dance World Magazine. Dance Canada Danse Archives. 1 (1): 2.

- ^ Anderson, Jack (October 5, 1990). "Norbert Vesak, 53, Former Chief of the Met Opera Ballet, Is Dead". The New York Times.

- ^ McLeod, Brian (September 17, 1969). "Vesak dancers mirror social schizophrenia". Vancouver Sun.

- ^ Dafoe, Christopher (1990). Dancing Through Time. Portage and Main. ISBN 978-0969426417.

- ^ Anderson, Jack (October 5, 1990). "Norbert Vesak, 53, Former Chief of the Met Opera Ballet, Is Dead". The New York Times.

- ^ "Into a Fantasy World: A History of Ballet". Canadian Broadcasting Company. September 7, 2004.

- ^ Terry, Walter (February 5, 1977). "The Met: A New Ballet Look". Dance Magazine.

- ^ Michael Crabb; Penelope Reed Doob. "Norbert Vesak". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Ecstasy of Rita Joe: Royal Canadian Ballet revisits Groundbreaking Work". Canadian Broadcasting Company. May 4, 2011.

- ^ Pepper, Kaija (2012). Renegade Bodies - Canadian Dance in the 1970s. Dance Collection Danse Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 9780929003702.

- ^ Pepper, Kaija (2012). Renegade Bodies: Canadian Dance in the 1970s. Dance Collection Danse Press. ISBN 978-0929003702.

- ^ Pepper, Kaija (2012). Renegade Bodies. Toronto: Dance Canada Danse. p. 14. ISBN 978-0929003702.

- ^ Dafoe, Christopher (1990). Dancing Through Time. Portage and Main. p. 70. ISBN 978-0969426417.

- ^ Craine, Debra (2010). Oxford Dictionary of Dance. Oxford University Press. p. 471. ISBN 978-0199563449.

- ^ "Triumphant, in Winnipeg". Dance Canada Danse Norbert Vesak Archives.

- ^ "Contemporary Dance Videos". Belong Pas de Deux. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- ^ "IMAX Is Believing". Archived from the original on June 26, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- ^ Neufeld, James (2011). Passion to Dance: National Ballet of Canada. Dundurn. p. 155. ISBN 978-1459701212.

- ^ Albertson, Kristi (March 11, 2007). "Fresh Legs". The Daily Inner Lake.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Review/Opera; More Zeffirelli on the Grand Scale In the Met's New 'Traviata'". The New York Times. October 18, 1989.

- ^ Anderson, Jack (October 5, 1990). "Norbert Vesak, 53, Former Chief of the Met Opera Ballet, Is Dead". The New York Times.

- ^ Lingg, Ann (January 1, 1977). "The House". The Metropolitan Mirror.

- ^ Anderson, Jack (October 5, 1990). "Norbert Vesak, 53, Former Chief Of the Met Opera Ballet, Is Dead". The New York Times.

- ^ Montee, Kristy (February 20, 1994). "This Ballet Premiere is Saga in Itself". Sun Sentinel.

- ^ Wyman, Max (1970). "Canada's Happiness Dancers". Dance Canada Danse Norbert Vesak Archives.

- ^ Montee, Kristy (February 20, 1994). "This Ballet Premiere is Saga in Itself". Sun Sentinel.

- ^ Montee, Kristy (February 20, 1994). "This Ballet Premiere is Saga in Itself". Sun Sentinel.

- ^ Anderson, Jack (October 5, 1990). "Norbert Vesak, 53, Former Chief Of the Met Opera Ballet, Is Dead". The New York Times.

- ^ Keane, Erin (October 1, 2012). "Doomed Love Affair Opens Ballet Season". WFPL News.

- ^ Morris, Bradley (January 30, 2013). "Bringing New Life to An Old Story". Urban Tulsa Weekly.

- ^ Montee, Kristy (1994). "This Ballet Premiere Is Saga In Itself". Sun Sentinel.

- ^ Montee, Kristy (February 20, 1994). "This Ballet: Premiere Is a Saga in Itself". Sun Sentinel.

- ^ Keane, Erin. "Doomed Love Affair Opens Ballet Season". WFPL News.

- ^ "Tulsa Ballet Stages Lady of the Camellias this February". January 17, 2013. Tulsa Ballet News.

- ^ Sunter, Robert. "Vesak Seeks Craft First". Vancouver Sun.

- ^ "Vesak wins top honors twice". Dance Magazine: 5–6. September 1980.

- ^ "Danse Collection Danse" (PDF). More Past Made Present. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2013-06-24.

- ^ Barber, James (May 16, 1970). "Why Lynn Seymour is back in town". Vancouver Sun.

- ^ Wyman, Max (June 25, 1969). "Virtuosity Amidst Quantity". Vancouver Sun.

- ^ Wyman, Max (August 20, 1971). "Banff's festival ballet excels Itself". Vancouver Sun.

- ^ "VESAK--A man bringing new concepts to acting". Vancouver Sun. February 14, 2013.

- ^ Hanahan, Donal (February 1, 1981). "Music View: The Rise of the Greater Miami Opera". The New York Times. Retrieved June 27, 2013.