Notre-Dame-de-la-Compassion, Paris

| Notre-Dame-de-la-Compassion | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Catholic Church |

| Province | Archdiocese of Paris |

| Region | Île-de-France |

| Rite | Roman Rite |

| Location | |

| Location | Place du Général Koenig, 17th arrondissement of Paris |

| State | France |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Chapel, parish church |

| Style | Neo-Byzantine architecture,Gothic architecture, Classical architecture |

| Groundbreaking | 1842 |

| Completed | 1843 |

| Designated | 1929 |

| Denomination | Église |

| Website | |

| www | |

Notre-Dame-de-la-Compassion is a Roman Catholic Church located on Place du Général Koenig in the 17th arrondissement in Paris. It was originally built in 1842–43 as a memorial chapel to Ferdinand Philippe, Duke of Orléans, the heir to King Louis-Philippe of France, who was killed in a road accident in 1842. It was built in the Neo-Byzantine style, with elements of Gothic, Baroque and other styles, and was originally called the Chapelle Royale Saint-Ferdinand. In 1970 it was moved stone by stone from its original location a short distance away to make space for the new Palais des Congrès. It became a parish church in 1993. Its notable decoration includes stained glass windows designed by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, and sculpture by Henri de Triqueti.[1] It was designated a French historic monument in 1929.[2]

History[edit]

The church was constructed as a memorial to Ferdinand Philippe, Duke of Orléans, the popular heir of King Louis Philippe I. The Duke was killed when he fell from his carriage and fractured his skull on the way to see his family at the royal chateau at Neuilly. Following his death, the Queen proposed the construction a memorial chapel at the place where the accident occurred, on the road to Neuilly.[3] It was dedicated to "Our Lady of the Compassion", the Virgin Mary, the Madonna for those killed in accidents.[4] The church was designed by Pierre François Fontaine and completed within two years by Pierre Bernard LeFranc. The tomb of the Duke is not in the chapel; it is found at the Chapelle royale de Dreux, with the tombs of the other members of the Orleans family.

The Duke was highly popular with the public, which his father, Louis Philippe I, was not. His death had important political consequences. The contemporary writer Alfred de Musset described his death as "One hour which turned around all of the century." The King was deposed soon afterwards during the French Revolution of 1848.[5]

In 1970, to make room for a new convention center, the chapel was taken apart stone by stone and moved to its present location at the Porte des Ternes. In 1993, it was formally made a parish church by the Archbishop of Paris under the name of Notre-Dame-de-la-Compassion, the name which had been chosen by Louis Philippe in 1843.[6]

Description[edit]

The architectural style is largely Neo-Byzantine, modelled after the ancient Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna, built between 425 and 450 AD. The plan of the small sanctuary is in the form of a Greek Cross. However, on top of this the architect added a variety of eclectic features; the arches borrow from Byzantine architecture, the capitals of the columns are from Merovingian architecture, the rose windows are from Gothic architecture, the furnishings are classical, and the vaults are inspired by Renaissance architecture. The church was considered an illustration of the "Juste milieu" or "Golden Mean", a popular philosophical concept in the period, seeking an absence of excess and a harmonious balance of styles.[7]

Exterior[edit]

The church is small in size, in the form of a Greek cross, a form borrowed from Byzantine architecture. It was moved I'm 1970 to its present location at the Porte des Ternes, at the edge of the city and between a major highway below and two converging streets.

-

The chapel is sited at the edge of the city, between the main highway around the city and two smaller streets.

-

Facade

-

Corner view

Interior[edit]

The interior of the church was planned by the painter Ary Scheffer, who was very popular at the time for his paintings featuring literary and religious themes; and who was very close to the Duke Ferdinand-Philippe d'Orleans. The interior was carefully designed to honour the Duke, and to express the romantic aesthetics of the period. The lighting and the architectural decoration in the interior are very subdued, to highlight the works of sculpture and stained glass.[8]

-

Nave and the Choir

-

The Altar and Apse

-

The coat-of-arms of Duke Ferdinand-Philippe d'Orleans in the north transept

-

North transept with cenotaph of the Duke

Sculpture[edit]

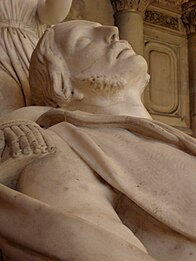

The major work of sculpture in the church is a cenotaph (a funeral monument to a person buried elsewhere) of Duke Ferdinand-Philippe d'Orléans, designed by the painter Ary Scheffer and made by the sculptor Henri-Joseph de Triqueti with Carrara marble, It depicts the Duke in his military uniform, as he was found on the road shortly before his death. Behind him is an angel in prayer, looking upwards with hands extended. This angel statue was made by Marie d'Orleans, a sculptor and the sister of the Duke.[9] The bas-relief on the base of the sculpture depicts "The Genius of France Weeping for Its Prince."

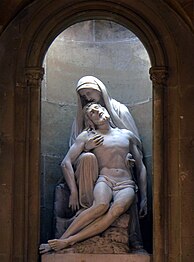

A sculpture in the chevet behind the altar, also by Henri-Joseph de Triqueti, depicts the Virgin holding the body of Christ on her knees. The features of Christ resemble those of Duke Ferdinand.[10]

-

Virgin of Compassion, by Henri-Joseph de Triqueti

-

Cenotaph of the Duke by Henri-Joseph de Triqueti, with an angel sculpted by Marie d'Orleans, sister of the Duke

-

Detail of cenotaph of the Duke

Stained glass[edit]

-

Rose window of Virgin and Child (over portal)

-

Cartoon made by Ingres for the rose window (1842) (The Louvre)

-

Rose window of the church, representing "Faith"

-

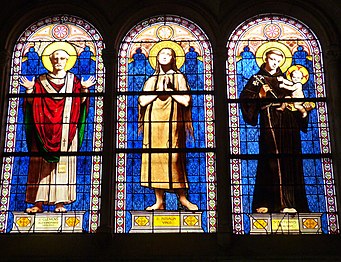

Patron saints of the family of Louis-Philippe and the Duke; Clement of Alexandria (left), Saint Rosalia (center) and Saint Anthony of Padua(Right)

-

Detail of the Archangel Raphael

-

Detail of Saint Louis (Louis IX of France), with features of Duke Ferdinand

-

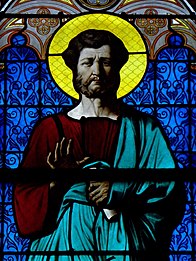

Detail of Saint Philip the Apostle

-

Detail of Saint Adelaide

The stained glass windows of the church are particularly notable. They were designed by the painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, who was a close friend of the Duke; King Louis-Philippe requested that Ingres make the windows.[11]

The windows were not made in the traditional Medieval style, with small pieces of coloured glass joined together with strips of lead; the images were painted onto the surface of the glass with enamel paints and then baked onto the glass at high heat. The glass-makers at the Sevres Porcelain workshop in Paris copied the full-size color drawings made by Ingres, which are now on display in the Louvre.[12]

See also[edit]

Notes and citations[edit]

- ^ Dumoulin, Aline, Églises de Paris (2017), p. 176

- ^ Dumoulin, Églises de Paris (2017), p. 176-179

- ^ [1] "Patrimoine-Histoire.fr" Site on the art and history of church (in French)

- ^ Dumoulin, Églises de Paris (2017), p. 176-179

- ^ Dumoulin, Églises de Paris (2017), p. 176

- ^ Dumoulin, Églises de Paris (2017), p. 176-179

- ^ Dumoulin, "Églises de Paris", (2017), p. 178

- ^ Dumoulin (2017) p. 178

- ^ Dumoulin (2017) p. 178

- ^ Dumoulin (2017) p. 178

- ^ [2]Patrimoine-Histoire site on the art and history of church (in French)

- ^ [3]Patrimoine-Histoire site on the art and history of church (in French)

Bibliography (in French)[edit]

- Dumoulin, Aline; Ardisson, Alexandra; Maingard, Jérôme; Antonello, Murielle; Églises de Paris (2017), Éditions Massin, Issy-Les-Moulineaux, ISBN 978-2-7072-0683-1

- Hillairet, Jacques; Connaissance du Vieux Paris; (2017); Éditions Payot-Rivages, Paris; (in French). ISBN 978-2-2289-1911-1