Peter Kharischirashvili

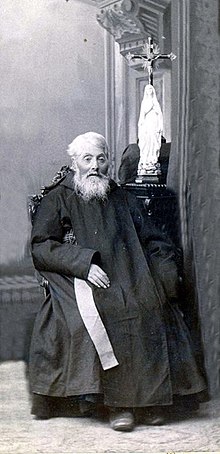

The Rev. Peter Kharischirashvili | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal | |

| Born | 1804 |

| Died | 7 October 1890 |

| Religion | Georgian Greek Catholic Church |

| Nationality | Georgian |

| Military service | |

| Rank | Priest |

| Senior posting | |

| Ordination | 1842 |

Peter Kharischirashvili[1] (in Georgian: პეტრე ხარისჭირაშვილი / ხარისჭარაშვილი, born in 1804 or 1805 in Akhaltsikhe, Tiflis Governorate, Russian Empire – 7 October 1890 in Constantinople) was a Georgian Catholic hieromonk, theologian, scientist and founder of the Servites of the Immaculate Conception.

Biography[edit]

Early years[edit]

Peter Kharischirashvili was born in 1804 or 1805 in Akhaltsikhe, according to most sources.[2][3] According to his tombstone, Kharischirashvili was born on May 2, 1818, which is the date accepted by Zakaria Chichinadze.[3] Meanwhile, other sources give his birth date as April 20, 1818.[4]

He studied at the parochial school and later went to study at the seminary in Gyumri, and finally to Rome to study Superior Theology.

Priesthood and last years in Georgian lands[edit]

In 1842 he returned to Akhaltsikhe, there he was ordained, and was appointed assistant archimandrite to Pavle Shahqulianis.[2][4] His return to Georgia also meant an awareness and a determination to fight so that Catholic Georgians could worship God in their native Byzantine Rite in the traditional Old Georgian liturgical language.[2][5]

Kharischirashvili captivated his faithful thanks to his eloquent preaching. Despite obeying the law and offering only the Badarak in Classical Armenian, he preached in the vernacular Georgian language. He worked hard to improve the situation of his people, exempting the dowry for women with few resources, and teaching people to read and write.[2] His authority, however, aroused suspicions among the Armenians. The tensions reached their highest point when the Armenians announced the decision to build a seminary at Akhaltsikhe and Shahqulianis supported them. Kharischirashvili faced him and, finally was sent to Khizabavra, and from there to Vale.[2]

In the 1850s he was transferred to Khizabavra (today's Aspindza region).

Sacerdotal life abroad[edit]

In 1856 he moved to Venice, where he joined the Armenian Catholic Church's Mekhitarist Congregation. He founded a Georgian language printing press and published a number of significant historical and theological books in the Georgian language on San Lazzaro Island. Kharischirashvili also translated books from Armenian, which he had found in the library of the Mekhitarist community. Thanks to his work, Pope Pius IX allowed him to found a new Georgian religious congregation on May 7, 1859, in Constantinople and also a typikon there.[2][4] Approval was given for the use of three rites, Roman Rite, Armenian Rite, and the Byzantine Rite in the traditional Old Georgian liturgical language.

Upon his arrival he founded the congregation of the Servites of the Immaculate Conception and began to celebrate the Byzantine Rite Divine Liturgy in Old Georgian.[2] A convent of nuns and a Catholic school were also founded. Each year the school had more than 100 students, many of whom were former Georgian serfs whose freedom was purchased by Fr. Kharischirashvili himself, and others who came from Georgia.[2] His work also attracted Orthodox and Muslim Georgians.[2]

In 1861, Fr. Kharischirashvili founded the first parish of the Georgian Greek Catholic Church in one of the most prestigious districts of Istanbul. As the Roman and Armenian Rites were the only Rites permitted by the House of Romanov for Catholics in Georgia within the Russian Empire, the Byzantine Rite in Old Georgian was offered mainly by the Servites at Constantinople, which was seen as the mother-house of their congregation.

Fr. Kharischirashvili spoke eight languages, but he paid particular attention to education in the Georgian language. In addition to theological work, his congregation and school have also had a significant influence upon the Georgian language, its grammar, literature, and history. Their pupils were also taught excerpts from Shota Rustaveli's The Knight in the Panther's Skin. The students were also taught Latin and French.

The school's students included, among others, Fr. Michel Tamarati and Mikheil Tarkhnishvili. In 1870, he founded a new Georgian printing press in Constantinople, and distributed many of the books free of charge to poor Georgian people. Fr. Kharischirashvili also paid special attention to ensure that every book was grammatically correct. Among his published works was a collection of his own poetry "ყვავილების კონა" ("Qvavilebis Kona").

The expansion of the Servite congregation caused a new monastery and publishing house to also be built at Montauban (France) in that same decade. Between 1877 and 1881 alone, the Servites in Montauban published and distributed over 25 different books in the Georgian language. Meanwhile, the Georgian Orthodox Church had lost both its autocephaly and Patriarchate to the Tsarist civil service in the Most Holy Synod, who were determined to use both Orthodoxy and the educational system as tools of linguistic imperialism and the coercive Russification, not only of the Georgian people, but of all other ethnic minorities. For this reason, they appointed ethnic Russians to the local hierarchy and forbade the State-controlled Georgian Orthodox Church to participate in the Georgian linguistic and literary revivals.

The Catholic Church, whether Roman, Armenian, or Byzantine Rite, remained independent, however, from control by the State. The Servites and their schools were accordingly able to continue the work of St. Gregory of Khandzta and laid the foundation for the subsequent mass revival of Georgian-medium education in Orthodox form by Prince Ilia Chavchavadze.

Death and legacy[edit]

He died on October 7, 1890, in Istanbul (other sources say October 9).[4] His headstone says:

OSSA PETRI CARISCIARANTI / GEORGIA DOMO DOMO AKALCIK / SERVORUM / ANCILLARUMQUE VIRGINIS / AB IMMACULATO CONCEPTU / INSTITUTORIS / AC MODERATORIS GENERALIS PRIMI / PIISSIMA VITA CESSIT / VII ID OCT MDCCCXC / VIXIT ANNOS LXXII MONTHS V TWELFTH XXVI RI P ".[6]

According to Father Christopher Zugger, nine Servite missionaries from Constantinople, headed by Exarch Shio Batmanishvili, came to the newly independent Democratic Republic of Georgia to permanently establish Catholicism of the Byzantine Rite in Old Georgian there, and by 1929 their faithful had grown to 8,000.[7] Their mission came to an end with the arrests of Exarch Shio and his priests by the Soviet secret police in 1928, their imprisonment in the Gulag at Solovki prison camp, and their subsequent murder by Joseph Stalin's NKVD at Sandarmokh[8] in 1937.[9]

Bibliography[edit]

- ბლუაშვილი, უჩა (2008). მესხეთის სახელოვანი შვილები / Славные сыновья Месхети (in Georgian and Russian). საქართველოს პარლამენტის ეროვნული ბიბლიოთეკა. pp. 70-76, 175-180. ISBN 978-9941-0-1076-7.

- ჭიჭინაძე, ზაქარია (1895). აბატი პეტრე ხარისჭირაშვილი. შარაძისა და ამხანაგობის სტამბა.

- Dalleggio, Eugène; Čičinaże, Zak'aria (2003). İstanbul Gürcüleri (in Turkish). Translated by Fahrettin Çiloğlu. Sinatle Yayınları. pp. 43-50. ISBN 9789758260157.

- კურტანიძე (Kurtanidze), ლ (L) (2002). "პეტრე ხარისჭირაშვილი და" სიბრძნე კაცობრივი " ". კავკასიის მაცნე / Caucasian Messenger (5). ISSN 1512-0619.

References[edit]

- ^ Also written as Cariscarian, Carisciarian, Caristchiarianti, Charistchiaranti, Charischiaranti, Karischiaranti, Karishiaranti, Kharistchirashvili, Kharistshirashvili, Harisçiraşvili, Hariscarianti, Krischiaranti, Харисчирашвили.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i ბლუაშვილი, უჩა (2008). მესხეთის სახელოვანი შვილები / Славные сыновья Месхети (in Georgian and Russian). საქართველოს პარლამენტის ეროვნული ბიბლიოთეკა. pp. 70-76, 175-180. ISBN 978-9941-0-1076-7.

- ^ a b Zakaria Chichinadze (1895). აბატი პეტრე ხარისჭირაშვილი . შარაძისა და ამხანაგობის სტამბა.

- ^ a b c d Dalleggio, Eugene; Čičinaże, Zak'aria (2003). İstanbul Gürcüleri (in Turkish). Translated by Fahrettin Çiloğlu. Sinatle Yayınları. p. 44. ISBN 9789758260157.

- ^ In the Russian Empire the Byzantine liturgy was reserved for the Georgian Orthodox, and Catholics could only celebrate the Armenian rite (Armenian language) or Roman rite (in Latin language).

- ^ Natsvlishvili, Natia (2015). "A struggle for identity: Georgian Catholics and their monastery in Istanbul". Caucasus Survey 3 (1). ISSN 2376-1199

- ^ Zugger, 2001 & The Forgotten: Catholics of the Soviet Union Empire from Lenin through Stalin, p. 213.

- ^ Zugger 2001, p. 236.

- ^ Zugger 2001, p. 259.

External links[edit]

- 1804 births

- 1890 deaths

- 19th-century poets from Georgia (country)

- Eastern Catholic priests from Georgia (country)

- Eastern Catholic monks

- Eastern Catholic poets

- Eastern Catholic writers

- Founders of Eastern Catholic religious communities

- Georgian Byzantine-Rite Catholics

- Male poets from Georgia (country)

- Mekhitarists

- Poet priests

- Poets from Georgia (country)

- Translators from Armenian

- Translators to Georgian