Phrenology and the Latter Day Saint movement

Phrenology has been a cultural factor in the Latter Day Saint movement (informally Mormons) since around the time of its founding in 1830.[1] Phrenology is a pseudoscience which involves the measurement of bumps on the skull to predict mental traits.[3][4] Developed in the 1790s, it became widely popular in the United States in the 1830s and 1840s, coinciding with the rise of the Latter Day Saint movement.[5]

Phrenology was never endorsed as a part of church theology or doctrine, but neither was it considered incompatible. This contrasts with the basic attitude of Orthodox Christian clergy, who generally condemned phrenology as "atheism, materialism, and determinism".[6] Phrenologists themselves considered themselves a secular science, compatible and even supporting of religion. Many early Latter Day Saints, including Joseph Smith, had phrenological readings done, and these readings were used by adherents and critics as supporting evidence of their respective viewpoints.[7]

The seriousness with which Latter Day Saints treated phrenology varied greatly, either considering them heretical, frivolous, amusing, or highly significant.[1] By the beginning of the 20th century, the respectability of phrenology began to decline, the appeal to Latter Day Saints subsequently faded away, and is currently generally frowned upon.[6]

Phrenology from 1830 through 1845[edit]

Book of Abraham Egyptian mummies[edit]

In 1835 the Church of the Latter Day Saints acquired four Egyptian mummies along with papyri from a larger collection of 11 mummies. Only four of the seven mummies Chandler sold before he met Joseph Smith have a current known location. Two mummies were sold by Chandler in Philadelphia to Dr. Samuel Morton who bought it for Philadelphia's Academy of Natural Sciences. These were dissected by Morton in front of other Academy Members. Morton was interested in the phrenology and would remove the skulls from the body, fill the skull with buckshot and then weigh the skull to determine the cavity size.[12][13] These two skulls reside at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology with other crania from the Morton Collection.[14] Several eyewitness accounts of the mummies purchased by the Church also gave phrenological commentary.[10][12]

Nauvoo Era[edit]

As the popularity of phrenology increased in the United States in the late 1830s and early 1840s, it became a routine, fashionable thing to obtain a reading.[1] Many Latter Day Saints obtained readings, including many of the leaders.[15]

Privately during the last four years of his life Joseph Smith rejected phrenology.[15] In January 1841 Smith said he received a revelation about phrenology, with "the Lord Rebuking him sharply in Crediting such a thing; & further said there was No Reality in such a science But was the works of the Devil"[16][17] On October 14, 1843, Smith engaged in a "warm debate" with a phrenologist and a mesmerist. Smith contended that they could "not prove that the mind of man was seated in one part of the brain more than another."[18]

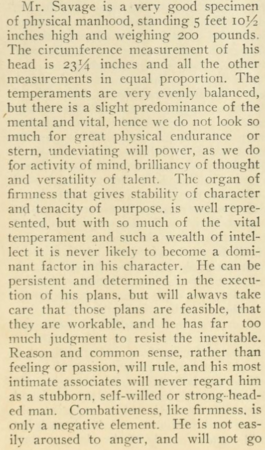

In contrast to his private stance, publicly Smith still permitted phrenologists to take readings, and allowed followers to publish them in friendly newspapers.[15] Joseph Smith consented to having phrenologists study his skull at least three times.[19] One of his phrenological charts was published in the Nauvoo newspaper The Wasp, along with an explanation that it was to satisfy a large number of people in many places who had "manifested a desire to know the Phrenological development of Joseph Smith's head."[20][21]

Smith's phrenological chart was re-printed by former counselor in the First Presidency John C. Bennett in 1842, as part of his exposé. Bennett used the chart as evidence to argue that Smith was naturally deceitful and untrustworthy.[23][24]

William Smith brother of Joseph Smith and the editor of the Nauvoo newspaper The Wasp, engaged in an editorial battle with Thomas C. Sharp, editor of the anti-Mormon newspaper, the Warsaw Signal. In his June 25, 1842, editorial, William Smith published an attack on Sharp, using elements of phrenology in a satirical article titled "Nose-ology" in reference to Sharp's large nose. Smith attacked "Thom-ASS C. Sharp" stating that "the length of his snout is said to be in the exact proportion of seven to one compared with his intellectual faculties, having upon its convex surface well developed bumps," and that these bumps signified fourteen traits, the first being "Anti-Mormonitiveness."[25]

Advertisements for books on phrenology were displayed prominently in nearly every edition of the church magazine The Prophet starting in May 1844, including those edited by William Smith, Samuel Brannan and Parley P. Pratt.[15] The January 25, 1845 edition produced an article sandwiched between conference reports and a hymn, explaining phrenology in detail, "for the benefit of all those who wish to investigate the science of phrenology."[2]

Brigham Young received at least two readings.[6] One occurred in Boston from famed phrenologist Orson Squire Fowler in 1843 along with Heber C. Kimball, Willford Woodruff and George Albert Smith. At the time Young was at least amused enough to copy his reading into his journal.[26] Later, Young noted that he was not impressed with Fowler or his reading, writing:

After giving me a very good chart for $1, I will give him a chart gratis. My opinion of him is, that he is just as nigh being an idiot as a man can be, and have any sense left to pass through the world decently; and it appeared to me that the cause of his success was the amount of impudence and self-importance he possessed, and the high opinion he entertained of his own abilities.[27]

Phrenology led to an increase in the popularity of making death masks, and could have been a contributing factor in the creation of Joseph Smith and Hyrum Smith's death masks.[28][29] Joseph and Hyrum's bodies were exhumed and moved several times to avoid vandalism and rising Mississippi River waters. In 1928, the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints moved the bodies to a safer location. The 1928 identification of the bodies was challenged in 1994. Phrenological charts taken of Joseph have been used in forensic analysis to confirm the identity of the exhumed remains.[30]

James H. Monroe, the Latter Day Saint school teacher of the children of Brigham Young and Joseph Smith, made phrenological charts for his pupils so that he could better understand their personalities and improve his teaching of them. He examined the heads of other Latter Day Saints, and was "fully satisfied in the truth of the science."[6]

The Nauvoo Neighbor, edited by apostle John Taylor, noted on May 14, 1845, that a phrenologist had been going around studying the skulls of those in Nauvoo, and that "nothing yet has been discovered more than is common to the heads of other cities, only that the Navooans have large bumps of patience and wisdom. ... he calculates some things about right."[31]

James Strang, leader of the Strangite branch of the Latter Day Saint movement, paid for a phrenological reading in the fall of 1846 in New York City, and published it in the first edition of his church's newspaper, the Northern Islander.[32] The newspaper also had frequent advertisements for phrelogists Fowler and Wells.[6]

Phrenology in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints after 1846[edit]

Interest in phrenology continued among members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) in Utah in the 1850s and beyond, mirroring a general interest in society at large.[33] The 1852 official Utah library contained five books with the word "phrenology" in the title, plus two with "physiognomy," and one with "phrenological" in the title, and every volume of American Phrenological Journal[15][34]

While crossing the plains to Utah, Heber C. Kimball and Colonel Thomas L. Kane came across a Native American burial mound on August 5, 1846. The next day, Kane paid some boys $2 to dig up the mound and remove the skeleton. Kane carefully wrapped up the bones and skull to take with him to Philadelphia "for the inspection of some professional friend of his who is versed in the science of Craniology."[35][36]

In February 1850 after the Battle at Fort Utah, between 40 or 50 heads were severed from the corpses of the Native Americans, collected, and boxed up so they could be shipped "to Washington to a medical institution" for craniological examination. The weather turned warm however and the heads turned green with rot and were disposed of before they could be shipped.[37]

When the Relief Society was reconstituted in the latter half of the 1860s, secular readings were assigned as part of a study program so the sisters could be well-rounded. A popular source for reading assignments in some wards was the Phrenological Journal.[6]

On his return from presiding over the British Mission, Apostle Orson Pratt visited the Fowler studio in New York City on 13 May 1867:

The Office was quite in commotion at the presence of a Mormon Apostle, and as a privilege both the principal phrenologist and the proprietor, Mr. Wells, had to lay hands on brother Orson's head, one after the other, not hearing each other, and then brother Pratt to their amusement and friendly feeling expressed a desire to do the same for them at some future time.[6]

Edward Tullidge, a disaffected member of the LDS Church in the late 1870s, joined the New Movement (Godbeite). He had connections with the editors of the widely distributed Phrenological Journal and used it as an outlet for a public relations campaign in the East.[39] In one article, he wrote about various leaders of the New Movement; of Elias L. T. Harrison he wrote that his forehead "massive with Causality, and Comparison very large," and that Henry W. Lawrence had the "head of the practical and enterprising man."[6]

Latter Day Saints George M. Ottinger and Charles Roscoe Savage owned a bookstore that sold publications of the Fowler & Wells Company owned by phrenologists Orson Fowler and Samuel Wells.[6] Ottinger and Savage provided photographs and paintings that the phrenologists valued, including a portrait of Brigham Young. They developed a friendly relationship, with Wells visiting "his friends" Ottinger and Savage, and Wells even publishing a biography of Ottinger complete with a favorable phrenological reading in the American Phrenological Journal in March 1869.[40] The friendship may have been a contributing factor in the Phrenological Journal taking a moderate position on Latter Day Saints physiology, a rarity in the scientific community in the 19th century when many were beginning to classify Mormons as degraded, and even a different race.[6][23]

A Scottish phrenologist, Dr. McDonald, visited Utah in 1872 and lectured in the Salt Lake Tabernacle, and in Provo to large audiences. Shortly thereafter a number of lectures were given by famed visiting phrenologist Orson Fowler, causing an excitement in Salt Lake City. In his opening lecture, he publicly gave a reading to Bishop Edwin D. Woolley, and editor of the Salt Lake Tribune, Elias L. T. Harrison. The Tribune reported that Fowler "disgusted very many of the audience" and that "any new beginner could have done better." Rival newspapers, the Deseret News and Salt Lake Daily Herald were generally more receptive and positive of Fowler.[6]

Fowler visited Utah again in late 1881. Twenty-three-year-old Latter Day Saint James Moyle (future politician and father of Apostle Henry D. Moyle) borrowed money to receive a reading, purchased a book, and attended three different lectures by Fowler. His reading said that he "would make a good teacher, or politician or lawyer." Moyle did end up becoming a lawyer and politician, but it is not known how much if any the impact his reading had on his career decision.[6] Fowler last visited Utah in 1884. At one of his lectures, he gave a public reading of William S. Godbe, a leader of the New Movement, during which the audience shouted out questions of Godbe's character that Fowler answered.[6]

Sarah Granger Kimball received a phrenological reading she valued, telling her that if she were "seated in a railway carriage with parties on one hand discussing fashions, and politics to be heard on the other, she would turn to the discussion of politics."[41][42]

Future Apostle George F. Richards journal indicate that phrenology was socially acceptable in the 1890s in Utah, himself enthusiastically attending phrenology lectures, and even had his own head read.[43]

The official history of the LDS Church included phrenology charts for Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball, but were removed by B. H. Roberts in 1902.[44]

Phrenologists in greater society classified and ranked human races from inferior to superior, with Indians and blacks ranked inferior and white races ranked higher, a system that has been thoroughly debunked but widely influential.[20] This thinking seeped into Latter Day Saint thought as well. For example, the highly influential[45] 1907 Deseret News five-volume book series The Seventy's Course in Theology by church seventy and prominent Mormon theologian B. H. Roberts quoted a passage from The Color Line by William Benjamin Smith, who used phrenology to argue against interracial marriage and social mingling with African Americans: "That the Negro is markedly inferior to the Caucasian is proved both craniologically and by six thousand years of planet-wide experimentation; and that the commingling of inferior with superior must lower the higher is just as certain as that the half-sum of two and six is only four."[46][47][48][49]

The Human Culture Company[edit]

Nephi Schofield and John T. Miller, were both returned missionaries of the LDS Church who graduated from different phrenological postsecondary schools in the late 1890s. Schofield served as a stake seventy in the LDS Church.[52] They began publishing articles in phrenological journals. Church president Wilford Woodruff consented to have a phrenological reading done, and on 28 February 27, Schofield obtained measurements and produced a phrenogram of Woodruff.[53]

Schofield and Miller opened a phrenological office in Salt Lake City, and in 1902 they started a phrenological magazine, called The Character Builder that continued into the 1940s. In November 1903 they created the Human Culture Company, with Miller as president and Schofield as vice-president, with the intent purpose of promoting phrenology. Stockholders of the company included Franklin S. Richards, Jesse Knight and others. In the year 1905 roughly 60,000 copies of The Character Builder were sold, plus several thousands books.[6]

The LDS Church purchased copies of the magazine and sent them to a few hundred missionaries. The Salt Lake Stake contributed $108.35 to the Human Culture Company. Lectures were given in many wards. Schofield left the company for an unknown reason around 1914. Miller continued on with the Character Builder, publishing phrenograms of several prominent Latter Day Saints from direct observation, including Orson F. Whitney and Evan Stephens. He also wrote several phrenological articles for LDS Church periodicals in the 1910s and 1920s.[6][54]

The 1930s and 1940s saw a precipitous decline in the acceptability of phrenology in society and within the LDS Church. Miller attempted to revive the movement by writing a letter to the Twelve Apostles, encouraging that phrenology be taught in LDS Church schools including Brigham Young University. Miller argued that respected teacher Karl G. Maeser was a phrenologist, a claim that is disputed.[55] The Apostles referred it to the First Presidency, who were cordial, but did not support the revival. From there, phrenology virtually vanished from the culture of the LDS Church.[6]

Impact on artwork[edit]

Phrenology had an impact on the appraisal of artwork among early 20th century Latter Day Saints. Some Latter Day Saints believed that since Jesus was a perfect individual, he would have phrenological and physiognomical attributes that should be reflected in the preferred artwork of the church.[56]

Analog to patriarchal blessings[edit]

Although phrenology extended into Latter Day Saint life as a cultural phenomenon, the LDS Church never threw its full support behind phrenology. Historians Davis Bitton and Gary Bunker postulate that this might be due to the appeal of a phrenological reading already being filled by a patriarchal blessing.[6] LDS Church president Ezra Taft Benson described a patriarchal blessing as "personal scripture ... the inspired and prophetic statement of your life's mission together with blessings, cautions, and admonitions as the patriarch may be prompted to give" that should be used as a guide in one's life.[57] Similarly, a phrenological reading was considered to be a personal scientific view of particular strengths and weaknesses of a person's mental traits, that was used as a decision making guide in a person's life. Bitton and Bunker note, "Without question far more Mormons obtained patriarchal blessings, copied them in their journals or otherwise cherished them, than obtained readings from phrenologists."[6]

Some Latter Day Saints did use phrenological readings to guide their lives. General Authority George Reynolds greatly valued his phrenology readings as much as he did his patriarchal blessing.[15] Apostle Rudger Clawson stated in a conference talk in 1898 that "a Phrenologist had once predicted that he would yet become an apostle."[15][58]

Aversion towards phrenology[edit]

Not all Latter Day Saints felt comfortable with phrenology. An 1841 article in the Times and Seasons warned about a man named Samuel Rogers, derogatorily referring to him as "a professed phrenologist".[59] Joseph Smith objected to an unnamed mesmerist and phrenologist performing in Nauvoo on May 6, 1843, because he "thought we had been imposed upon enough by such kind of things."[6]

An 1864 article in the Millennial Star titled "Remarks on Phrenology", while not discrediting phrenology, urged readers to approach it with caution, citing the difficulty of reading bumps, and that blood had as much to do with personality as brain size:

The Book of Mormon furnishes abundant proofs to show that the tribe of Manasseh had many men eminent for their love of God and devotedness to the Gospel. Now, on the contrary, we do not find any history proving that the Negroes, the descendant of Ham, embraced the Gospel, organized a Church, and had the gift of the Holy Spirit with them, as did the descendants of Joseph. By this comparison we may conclude that blood, as well as an organization and position of bumps gives intellect to perceive truth and piety to serve the Lord.[60]

George Q. Cannon added an editorial after the article endorsing it and encouraged using the "Spirit of God" as a guide, but also noted, "We do believe there is some truth in phrenology."[6][60] When Fowler visited Utah Territory in 1872, Cannon discouraged elders of the church from patronizing him, insinuating that phrenological readings were part of what led Amasa Lyman and others into apostasy.[61]

Phrenology in apologetics[edit]

In 1901, Henry Stebbins of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints used craniology to argue that ancient cliff-dweller Native Americans could be the Nephites or Jaredites, "The skulls were shaped like the skulls of white people, a very distinct and different people from the Indians. ... There appears to be abundant proof of the superiority of the ancient Americans in color, in skull structure and shape. ... according to both the Book of Mormon and science, it was not the red man who built cities and erected palaces. It was a nobler race, and they remained fair until they amalgamated with the Lamanites and were brought under the same cursing.[62]

This apologetic was disputed using craniology by Charles Shook in 1914. After surveying skull characteristics throughout the Americas he concluded, "Even those who have held that the 'veritable Mound Builders' were a race superior to the North American Indians have been forced to concede that their crania are of the Indian type."[63]

In May 1902, Nephi Schofield wrote for the LDS Church magazine Juvenile Instructor, a detailed two-part phrenological sketch of Joseph Smith from portraits, in which he confirmed "scientifically" that Smith's mission was divine.[6] Schofield argued that the "prominence of the lower portion of the forehead" showed that Smith was "physically incapable of conceiving a plan of redemption that even approaches the magnitude of ... 'Mormonism'".[64] Furthermore, he pointed to phrenological evidence that Smith did not possess the character qualities of "excessive imagination" or "willful deception" that would have been necessary to invent his visions.[65]

Outside phrenological views of Latter Day Saints[edit]

Phrenology and the related pseudoscience physiognomy were often used in the 19th century to argue that Latter Day Saints were inferior, to the point that some even argued that Mormons were evolving into a different race, inferior to other whites. This especially became true as influxes of undesirable converts from perceived inferior white ethnic groups and social classes immigrated to Utah.[20][38]

A physiognomist in 1852 argued that Joseph Smith had a "particularly strong" resemblance to a type of bear, "which bears the strongest resemblance to the hog. ... as ugly in disposition as in looks." This outward appearance of Smith demonstrated characteristics of "a sneaking, under-ground miner, descending lower than the hog, delving for sordid gain, pandering to the strongest. Is such a resemblance to bears, that disgrace the name of their species, to be found on the western continent?"[66]

One physiognomist in 1879 used Brigham Young as an example of a person who lacked what he called monoeroticity, or dedication to monogamous relationships. The argument was the shape of Young's eyes were narrow, and thus more prone to polygamous relationships that lacked dedication.[20][67][68]

Additionally, phrenology was used to explain that Mormon males were naturally drawn towards polygamy.[20] In his 1870 exposé on Mormonism, J. H. Beadle voiced this argument, stating that Joseph Smith's high marks in "amativeness" on his phrenology chart show that Smith's "sexual passion" were the real reason for the doctrine of polygamy.[69][70]

The 1871 Phrenological Journal ran five separate articles on Mormon themes, treating Mormons as a physically different population. This was distinct from the treatment given to other religious groups such as Methodists, Presbyterians and Baptists. The journal tended to be more moderate in its portrayals of the Latter Day Saints.[20] After analyzing hundreds of Mormon heads, results did not support the common belief was that polygamy produced degraded children, and even noted that the majority of Mormons did not practice polygamy. However the journal did note that polygamy was only "found in primitive societies". Skulls of leaders scored high marks in religious and moral regions, but low in high culture. Converts were called "dupes" and "simple minded", but overall had "the capacity and weight of the Anglo-Saxon head" which the journal considered to be superior.[20]

Gallery of phrenology readings[edit]

-

John C. Bennett's Phrenology chart taken in 1839 or 1840[71]

-

Willard Richards phrenology reading as published in Nauvoo Wasp on 9 July 1842.[74] Re-printed in the History of the Church.[75]

-

Wilford Woodruff phrenological chart received on September 20, 1843. As published in apostle Matthias F. Cowley's 1909 biography of Woodruff.[77]

-

Heber C. Kimball reading taken in April 1842, published by Apostle Orson F. Whitney in 1888, noting that "it is, in many respects, and excellent index of Heber's character and idiosyncrasies". Also published on the front page of the October 31, 1855 Deseret News.[78][79][80]

-

George M. Ottinger phrenological reading, published in the American Phrenological Journal in March 1869[6][82]

-

Phrenology reading of William S. Godbe on June 3, 1884, as published in the Deseret News the next day[83]

-

Phrenograph of Charles Roscoe Savage performed by Nephi Schofield in 1904. Published in the phrenological journal The Character Builder.[84]

See also[edit]

- Cunning folk traditions and the Latter Day Saint movement

- List of references to seer stones in the Latter Day Saint movement history

- Salamander letter

- The Magus (book)

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d David J. Whittaker "Almanacs in the New England Heritage of Mormonism" Brigham Young University Studies Vol. 29, No. 4 (FALL 1989), pp. 89-113

- ^ a b c William Smith, George T. Leach (December 6, 1844). "The Prophet, 1844–1845" – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Wihe, J. V. (2002). Science and Pseudoscience: A Primer in Critical Thinking. In Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience, pp. 195-203. California: Skeptics Society.

- ^ Hines, T. (2002). Pseudoscience and the Paranormal. New York: Prometheus Books. p. 200

- ^ McCandless, Peter (1992). "Mesmerism and Phrenology in Antebellum Charleston: "Enough of the Marvellous"". The Journal of Southern History. 58 (2): 199–230. doi:10.2307/2210860. JSTOR 2210860.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Davis Bitton and Gary L. Bunker, Phrenology Among the Mormons, Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, Volume 9, number 1. Spring 1974 pages: 42-61

- ^ Leaders that had phrenological readings done include Joseph Smith, Hyrum Smith, Brigham Young, George A. Smith, John E. Page, Amasa M. Lyman, Charles C. Rich, George Q. Cannon, Daniel H. Wells, Abraham H. Cannon, Matthias F. Cowley, Orson F. Whitney, Rudger Clawson, Wilford Woodruff, George F. Richards, Sarah Granger Kimball. See Quinn, D. Michael. Early Mormonism and the Magic World View. Signature Books, 1998 e-book location 20343 of 23423

- ^ "Crania Aegyptiaca, or, Observations on Egyptian ethnography derived from anatomy, history and the monuments/ by Samuel George Morton". London : J. Penington. December 6, 1844 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Wolfe, S. J., and Robert Singerman. Mummies in Nineteenth Century America: Ancient Egyptians as Artifacts. McFarland & Co, 2009. pg. 106

- ^ a b "Expedition Magazine - Penn Museum". www.penn.museum.

- ^ Peterson, H. Donl. The Story of the Book of Abraham: Mummies, Manuscripts, and Mormonism. CFI, 2008. pg. 93

- ^ a b Peterson, H. Donl. The Story of the Book of Abraham: Mummies, Manuscripts, and Mormonism. CFI, 2008. pg 93

- ^ Samuel Morton, "Observations on Egyptian Ethnography, Derived from Anatomy, History, and the Monuments,"

- ^ Provo, Utah, Daily Herald for Sunday, November 23, 1980, p. 59

- ^ a b c d e f g h Quinn, D. Michael. Early Mormonism and the Magic World View. Signature Books, 1998 e-book location 20343 of 23423

- ^ Andrew F. Ehat and Lyndon W. Cook eds. "The Words of Joseph Smith:The Contemporary Accounts of the Nauvoo Discourses of the Prophet Joseph" Grandin Book Co. 1991. page 61

- ^ "January 5, 1841". www.boap.org.

- ^ George D. Smith ed. "An Intimite Chronicle: The Journals of William Clayton" Signature Books, May 1995 page 121

- ^ Once in Philadelphia on 14 Jan. 1840, another time in Nauvoo on 2 July 1842, published in The Wasp, and a third time by Dr. Turner on October 13, 1843]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Reeve, W. Paul. Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness. Oxford University Press, 2017. page 26

- ^ "The Wasp 1842 1843". December 6, 1842 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Phrenology Chart, 14 January 1840–B," p. [1], The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed May 13, 2020

- ^ a b Givens, Terryl. The Viper on the Hearth: Mormons, Myths, and the Construction of Heresy. Oxford University Press, 2013. page 148.

- ^ Bennett, John Cook (December 6, 1842). "The history of the saints : or, An exposé of Joe Smith and Mormonism". Boston : Leland & Whiting; New York : Bradbury, Soden, & co.; [etc., etc.] – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "The Sting of the Wasp". August 6, 2019.

- ^ John G. Turner, "Brigham Young:Pioneer Prophet", Harvard University Press (September 25, 2012). page 100

- ^ E. J. Watson, ed., "Manuscript History of Brigham Young", pp. 150-51.

- ^ Gibson, I. (1985). Death Masks Unlimited. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Edition), 291(6511), 1785-1787. Retrieved May 14, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/29521702

- ^ Church History Joseph and Hyrum Death Masks The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints 25 July 2019

- ^ "Curtis G. Weber, "Skulls and Crossed Bones?: A Forensic Study of the Remains of Hyrum and Joseph Smith," Mormon Historical Studies, vol. 10, no. 2 (2009), 1" (PDF).

- ^ "Nauvoo Neighbor, 1843–1845". December 6, 1843 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "For His Was The Kingdom, And The Power, And The Glory … Briefly | AMERICAN HERITAGE". www.americanheritage.com.

- ^ For early 1850s example, A letter to the editor of the Phrenological Journal in 1852 by Mrs. L. G. W. of Salt Lake City said,

American Phrenological Journal, 17(1853), 47"The Phrenological Journal has taught me how to govern and instruct my children, how to know a good person from a bad one, and is a never ending source of reflection, knowledge, and happiness. Large charts of heads hung up in a convenient place in a house for children to look at, soon interest them and by degrees they acquire a knowledge of the science."

- ^ Catalogue of the Utah Territorial Library, October, 1852 (Salt Lake City: Brigham H. Young, 1852), 12, 13, 14, 41, 60.

- ^ Richard E. Bennett, "The Journey West: The Mormon Pioneer Journals of Horace K. Whitney with Insights by Helen Mar Kimball Whitney" Religious Studies Center (June 25, 2018) e-book location 2775 of 11105

- ^ Matthew J. Grow, Ronald W. Walker, editors, "The Prophet and the Reformer: The Letters of Brigham Young and Thomas L. Kane" Oxford University Press, May 1, 2015. page 29

- ^ John Alton Peterson, "Utah's Black Hawk War" (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1998), Pages 56-57.

- ^ a b "The American Phrenological Journal and Life Illustrated". Fowler and Wells. December 6, 1866 – via Google Books.

- ^ Walker, R. (1976). Edward Tullidge: Historian of the Mormon Commonwealth. Journal of Mormon History, 3, 55-72. Retrieved May 25, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/23286158

- ^ "The American phrenological journal and life illustrated : a repository of science, literature, and general intelligence". New York : Fowler and Wells. December 6, 1861 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Jill Mulvay Derr (1976), Sarah M. Kimball, Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society Published as a pamphlet by Signature Books in 1981.

- ^ "Representative women of Deseret, a book of biographical sketches to accompany the picture bearing the same title. Comp. and written by Augusta Joyce Crocheron". Salt Lake City, Printed by J. C. Graham & Co. December 6, 1884 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "George F. Richards, Journal, 27, 29 Jan. 1891, The Journal of George F. Richards, Church Historian's Press, accessed 6 Apr. 2020".

- ^ "Dean C. Jessee, The Reliability of Joseph Smith's History, Journal of Mormon History, Volume 3, 1976 page 43" (PDF).

- ^ Brooks, Joanna (May 2020). Mormonism and White Supremacy: American Religion and The Problem of Racial Innocence. New York City: Oxford University Press. p. 75. ISBN 9780190081751.

The theological system of instruction [The Seventy's Course in Theology Vol 1-5] developed by Roberts played a critical role in LDS institutional history.

- ^ Smith, William Benjamin (1905). The Color Line: A Brief on Behalf of the Unborn. New York: Phillips & Company. p. 12.

- ^ Roberts, Brigham Henry (1907). The Seventy's Course in Theology, Vol. 1. Salt Lake City: Deseret News. pp. 165–166.

- ^ Brooks, Joanna (May 2020). Mormonism and White Supremacy: American Religion and The Problem of Racial Innocence. New York City: Oxford University Press. pp. 73–75. ISBN 9780190081751.

- ^ Anderson, Emily (July 3, 2018). "Tanner Humanities Center Hosts Conference on Race in the LDS Church".

- ^ a b Miller, John T. (December 6, 1904). "The Character builder: A journal of human culture and hygeio-therapy, 1904". Salt Lake City, UT: Human Culture Company – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Miller, John T. (December 6, 1908). "The Character Builder: Devoted to personal and social betterment, 1908". Salt Lake City, UT: Human Culture Company – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Nephi Young Schofield | My Ancestor in Church History". history.churchofjesuschrist.org.

- ^ a b "The Phrenological journal and science of health, incorporated with the Phrenological magazine". December 6, 1838: 124 v – via HathiTrust.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ John T. Miller "Marriage Adaptations," Young Woman's Journal, 21 (1910) 98

"The Mirror of the Mind," Young Woman's Journal, 23 (1912), 547-49

"Character Analysis of President Brigham Young," Young Woman's Journal, 30 (1919), 330-332

"Dr. Karl G. Maeser: The Character Builder", Improvement Era, 32 (May 1929), page 386

"Character of President Brigham Young," Improvement Era, 32 (June 1929), 639-641. - ^ Maeser, Karl G. (December 6, 1898). "School and fireside". [Utah] : Skelton – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Noel A. Carmack "Images of Christ in Latter-day Saint Visual Culture, 1900–1999" BYU Studies, Journal 39:3, page 34.

- ^ Ezra Taft Benson, "To the 'Youth of the Noble Birthright'", Ensign, May 1986, pp. 43–44

- ^ Abraham Owen Woodruff diary, 9 Oct. 1898, LDS archives. The reference to phrenology was deleted from the official publication of Clawson's talk in Conference Report ... October 1898(Salt Lake City: Deseret News Publishing, 1898), 53-54.

- ^ "Times and Seasons". F. Ullmann. December 6, 1841 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b "The Latter-Day Saints' Millennial Star". P.P. Pratt. December 6, 1864 – via Google Books.

- ^ Minutes of the School of the Prophets, 20 January 1872, Church Archives, as quoted in Davis Bitton and Gary L. Bunker, "Phrenology Among the Mormons, Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, Volume 9, number 1. Spring 1974 pages: 42-61

- ^ Henry A. Stebbins, "Book of Mormon Lectures", Board of Publication of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, Lamoni Iowa, 1901 page 104, 176.

- ^ "Charles A. Shook's 1910 book, part 1". www.olivercowdery.com.

- ^ "Juvenile Instructor". Salt Lake City George Q. Cannon Deseret Sunday School Union 1866-1929. May 1, 1902 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Juvenile Instructor". Salt Lake City George Q. Cannon Deseret Sunday School Union 1866-1929. May 15, 1902 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Redfield, James W. (December 6, 1866). "Comparative physiognomy : or, Resemblances between men and animals". New York : W. J. Widdleton – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Simms, Joseph (December 6, 1879). "Nature's revelations of character". New York, D. M. Bennett – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Gary L. Bunker and Davis Bitton "Polygamous Eyes: A Note on Mormon Physiognomy"" (PDF). Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. p. 118.

- ^ Ricketts, Jeremy (August 19, 2011). "Imagining the Saints: Representations of Mormonism in American Culture". American Studies ETDs.

- ^ Beadle, J. H. (John Hanson) (December 6, 1870). "Life in Utah". Philadelphia, Pa.; Chicago, Ill., [etc.]: National Publishing Company – via Internet Archive.

- ^ >Bennett, John C. (1842). History of the Saints; or, an Exposé of Joe Smith and Mormonism. Boston: Leland & Whiting. full chart

- ^ A. Crane, M.D. "A Phrenological Chart" Nauvoo Wasp July 2, 1842. full chart

- ^ History of the Church Volume 5:53-55, pages 58-60. full chart

- ^ A. Crane M. D., "Phrenological Reading" Nauvoo Wasp 9 July 1842 full chart

- ^ History of the Church Volume 5:53-55, pages 58-60.

- ^ A. Crane M. D., "Phrenological Reading" Nauvoo Wasp 9 July 1842 full chart

- ^ Mathias F. Cowley, "Wilford Woodruff: History of His Life and Labors", page 193, 194

- ^ Orson F. Whitney, "Life of Heber C. Kimball", published by the Kimball Family, 1888. page 328.

- ^ Kimball, Stanley B. (1975) "Heber C. Kimball and Family, The Nauvoo Years," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 15 : Iss. 4, Article 7

- ^ "Phrenological Chart of Elder Heber C. Kimball," Deseret News [weekly], 31 Oct. 1855, 265-66

- ^ Journal of Alfred Cordon. May 24, 1844

- ^ March 1869 American Phrenological Journal, page 109.

- ^ Deseret News, "Fowler on Phrenology", June 4, 1884. page 3

- ^ Nephi Schofield, "Charles R. Savage: A Phrenograph from a Personal Examination", The Character Builder, 1904, page 72. complete phrenograph

![Joseph Smith's Phrenology Reading published in the Nauvoo Wasp on 2 July 1842.[72] Re-printed in the History of the Church.[73]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/49/Joseph_Smith_Phrenology_Reading_Nauvoo_Wasp_2July1842.PNG/209px-Joseph_Smith_Phrenology_Reading_Nauvoo_Wasp_2July1842.PNG)

![Willard Richards phrenology reading as published in Nauvoo Wasp on 9 July 1842.[74] Re-printed in the History of the Church.[75]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b7/Willard_Richards_Phrenological_Reading_Nauvoo_Wasp_9_Jul_1842.PNG/246px-Willard_Richards_Phrenological_Reading_Nauvoo_Wasp_9_Jul_1842.PNG)

![Wilford Woodruff phrenological chart received on September 20, 1843. As published in apostle Matthias F. Cowley's 1909 biography of Woodruff.[77]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/74/Wilford_Woodruff_Phrenology_Chart_September_20_1843.png/424px-Wilford_Woodruff_Phrenology_Chart_September_20_1843.png)

![Heber C. Kimball reading taken in April 1842, published by Apostle Orson F. Whitney in 1888, noting that "it is, in many respects, and excellent index of Heber's character and idiosyncrasies". Also published on the front page of the October 31, 1855 Deseret News.[78][79][80]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a9/Heber_C_Kimball_Phrenology_Reading.PNG/458px-Heber_C_Kimball_Phrenology_Reading.PNG)