Qalaherriaq

Erasmus Augustine Kallihirua | |

|---|---|

| Qalaherriaq | |

Portrait, early 1850s | |

| Born | c. 1834 |

| Died | June 14, 1856 St. John's, Newfoundland Colony |

| Signature | |

Qalaherriaq (Greenlandic pronunciation: [qɑlɑheʁːiɑq], c. 1834 – June 14, 1856), baptized as Erasmus Augustine Kallihirua, was an Inughuit hunter from Cape York, Greenland, recruited in 1850 as an interpreter by the crew of HMS Assistance during the search for Franklin's lost expedition. He produced maps of Northern Greenland for the expedition, and guided the ship to Wolstenholme Fjord to investigate rumors of a massacre of Franklin's crew. Although it was initially planned to return him to his family after the expedition, poor sea conditions made landing at Cape York impossible, and he was taken to England and placed under the care of the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. Enrolled at St Augustine's College in Canterbury, Qalaherriaq studied English and Christianity for several years. He was appointed by the Bishop of Newfoundland Edward Feild to accompany him on religious missions to the Inuit of Labrador. Plagued by illness since his time aboard the Assistance, he died at St. John's from complications of long-term tuberculosis in June 1856.

Name[edit]

Qalaherriaq was known by various names. Qalaherriaq or Qalaherhuaq are approximations of his name's pronunciation in his native dialect of Inuktun, rendered as Qalasirssuaq in standard Greenlandic (Greenlandic pronunciation: [qɑlɑsiʁsːuɑq]). This was rendered Kallihirua in contemporary sources, and frequently abbreviated "Kalli".[1] He was named Erasmus York (after Captain Erasmus Ommanney and Cape York),[2] before his baptism in 1853 as Erasmus Augustine Kallihirua. Other spellings of his name include Caloosa, Calahierna, Kalersik, Ka’le’sik, Qalaseq, and Kalesing.[1]

Early life and European contact[edit]

Qalaherriaq was born around 1834[a] to Qisunnguaq and Saattoq,[b] members of an Inughuit band near Cape York and Wolstenholme Fjord in northwestern Greenland.[4] He had a younger sister, and perhaps another younger sibling, both of whose names are unknown.[5] His band, situated near auk-hunting grounds,[6] was encountered by various ships searching for a lost British exploring mission.[7]

Search for Franklin's expedition[edit]

In 1845, Sir John Franklin commanded an expedition attempting to transit the final uncharted sections of the Northwest Passage in what is now western Nunavut. The two ships under Franklin's command, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, were trapped by ice in the Victoria Strait. The ships were abandoned in April 1848, and all remaining crew members presumably died while attempting to traverse the Canadian Arctic mainland. In March 1848, when the expedition had been out of contact for several years, the Admirality launched a series of expeditions to locate whatever remained of Franklin's expedition. A large expedition was outfitted in 1850 following lobbying by Franklin's widow, Jane.[8]

On August 12, 1850, the brigs HMS Lady Franklin and HMS Sophia, under the command of whaler and explorer William Penny, reached the coast of Cape York. Upon sighting an approaching Inughuit kayak, Sophia anchored. The three men aboard the kayak were invited on deck to meet with Penny's interpreter, Johan Carl Petersen, a Dane from Upernavik. Petersen inquired for information relating to Franklin's expedition, but the relatively large number of European ships previously sighted in the region, coupled with the Inughuit's great excitement aboard the vessel resulted in no useful information, and the Inughuit returned to shore.[7]

Cape York landing[edit]

The following day, Prince Albert and HMS Assistance spotted the same group of Inughuit. A landing party, including Captains Charles Forsyth and Erasmus Ommanney went to shore. They were greeted by two young men, including Qalaherriaq.[9] However, none of the landing party could speak Inuktun, and were unable to communicate with the band ashore. They were shortly joined by Captain John Ross and his Kalaallit interpreter, Adam Beck.[10] After a long conversation, the only ship that could be readily identified was the North Star, a supply ship which had passed through the region during another search for Franklin's expedition.[10]

Upon the officers' return to their ships, Beck became notably distressed. Beck explained that the Inughuit mentioned an additional ship that had passed through the area in 1846 staffed by naval officers, which was massacred by another Inughuit band while camping ashore at Wolstenholme Fjord. Ommanney and Petersen returned to the shore to interrogate the Inughuit band further, suspecting that Beck may have invented the story, or that alternatively the band may have been responsible for the massacre. When the same information about the North Star was repeated to the explorers and denied any violence against the British, Ommanney recruited Qalaherriaq to serve as an interpreter on the Assistance.[11][5]

Interpreter service[edit]

When asked by Captain Ommanney to sketch the coast, he took up a pencil, a thing he had never seen before, and delineated the coast-line from Pikierlu to Cape York, with astonishing accuracy, making marks to indicate all the islands, remarkable cliffs, glaciers, and hills, and giving all their native names

C. R. Markham, Arctic Geography and Ethnology, 1875 [12]

Qalaherriaq was described in Ommanney's diary as readily volunteering to go with the expedition, without even returning to camp to gather his possessions. Later British sources state that he was fully ready to "remain under the captain’s own personal care, and be with him always", and that he had stoically accepted his role as an interpreter due to a lack of surviving family; however, this account has been heavily disputed by later scholarship.[13]

Significant contradictions exist between period descriptions of Qalaherriaq's volunteering to service. Snow's 1851 account, Voyage of the Prince Albert in Search of Sir John Franklin, describes him as a "young man without father or mother", while Petersen's 1857 Erindringer Fra Polarlandene describes him as being unbothered by leaving his mother.[5] Qalaherriaq was originally supposed to be returned to his family after guiding the Assistance to Wolstenholme Fjord.[14]

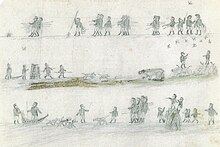

Upon boarding the Assistance, Qalaherriaq was washed and dressed in European clothing. He was given the name Erasmus York, although continued to be called variations of his birth name while aboard. He was seen as a curiosity and "the life of the party" by the crew, who recruited him to participate in the "Royal Arctic Theatre", a trope of theatrical performances. Ommanney described him as "an interesting specimen of uncivilised life."[15][16] He was the subject of a satirical article published in the Northern Lights, a ship newspaper published aboard the Assistance, where the Inuk is depicted as praising European civilization, while making various naïve and childlike statements about ship life, including a joke about him misidentifying sailors cross-dressing during a masquerade as shamanic spirits.[17][18] While on board the Assistance, Qalaherriaq drew several detailed maps of the surrounding fjords.[19]

Wolstenholme Fjord[edit]

Qalaherriaq guided the Assistance to Wolstenholme Fjord where the Europeans investigated the claims of a massacre of Franklin expedition.[20] The crew encountered several abandoned igluit at the site of Uummannaq, now Pituffik. Inside one igloo, the crew found a heaped pile of seven bodies, the survivors were assumed to have fled the area without burying the dead due to an epidemic. The crew excavated several graves, finding both Inuit and British seamen from the North Star. An officer examined a grave and removed a narwhal tusk spear placed atop the grave, a type of Inughuit grave artifact commonly looted by British explorers for the collections of anthropological museums. Qalaherriaq cried and begged him to put the spear back, recognizing the grave as being that of his father, Qisunnguaq. The grave was repaired by another officer and the spear, considered in Inughuit customs to be used by the dead for protection in the afterlife, was returned.[6][20]

With sea conditions rendering return to Cape York impossible, the Assistance crossed Baffin Bay and wintered at Griffith Island, near the present location of Resolute.[4] Icebergs continued to pose a threat the following spring, and the ship began the return trip to England without returning Qalaherriaq to his family.[6]

Early 20th century Inughuit oral histories describe Qalaherriaq as being abducted by the explorers, with his mother mourning his disappearance without ever learning of his fate.[21] The loss of a adolescent son, expected to hunt for the family, would place a great material burden on his mother and siblings, especially during an era marked by severe hardship for the Inughuit.[3][22]

England[edit]

Qalaherriaq arrived in England in the autumn of 1851 aboard the Assistance, and was brought to the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.[4] In October 1851, he visited the Great Exhibition in London alongside Reverend George Murray of the Society, one of a group of clergy and officers who served as caretakers to Qalaherriaq.[23][24]

I be in England long time none very well – very bad weather ... very bad cough – I very sorry – very bad. Weather dreadful. Country very different – another day cold another day [h]ot. I miserable.

Qalaherriaq, letter, April 1853[25]

In November, at the recommendation of the Admiralty and the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, he was placed in St Augustine's College, a Church of England missionary college in Canterbury. Here he learned to read and write while receiving a religious education. During his time at St Augustine's, he additionally served as an apprentice to a local tailor. From 1852 to 1853 he was interviewed by Captain John Washington for a revised edition of his Greenlandic linguistics text, Eskimaux and English vocabulary, for the use of the Arctic expeditions.[4] By September 1852, he had made some progress in English but struggled with reading. He was reported to greatly enjoy writing, and made friendships with younger children in his spelling classes.[26]

Qalaherriaq suffered from a chronic illness since his time on the Assistance. He coughed frequently, and by the spring of 1853 was bedridden for several days during a period of poor weather.[27] On November 27, 1853, he was baptized as Erasmus Augustine Kallihirua at St. Martin’s Church in Canterbury, in a ceremony attended by Captain Ommanney and various ministers and clergy, alongside various members of "the poorer class to whom Kalli is well known".[28] At some point while in England, he sat for a life-size double portrait by an unknown artist, which some decades later was donated for display at the Royal Navy College in Greenwich.[29]

Newfoundland and death[edit]

Appointed by Edward Feild, the Bishop of Newfoundland and the Warden of St Augustine's, Qalaherriaq was sent to the Newfoundland Colony to assist missionary efforts among the Inuit of Labrador. To support this, he was given a £25 per year stipend.[30] He arrived at St John's, Newfoundland on October 2, 1855. Although all were Inuit languages, Qalaherriaq's dialect of Greenlandic was a distinct language from the Nunatsiavummiutitut dialect of Eastern Canadian Inuktitut, and Qalaherriaq struggled to communicate with a Moravian missionary from Labrador.[31] He attended the Theological Institute (now Queen's College, part of the Memorial University.[4] While in Newfoundland, he practiced ice skating, but continued to suffer from chronic illness.[32]

Qalaherriaq planned to accompany the Bishop of Newfoundland on missionary work to Labrador in the summer of 1856. However, after swimming in cold water at St. John's, his health declined rapidly. Bedridden for a week, he died on June 14, 1856.[4] An autopsy done in the following weeks concluded that he died of heart failure associated with long-term tuberculosis.[33] A short biography, Kalli, the Esquimaux Christian, was published by Reverend Murray in 1857, becoming the main primary source on Qalaherriaq's life.[23]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c Høvik & Jeremiassen 2023, pp. 976–977.

- ^ Harper, Kenn (June 17, 2005). "Taissumani: A Day in Arctic History June 14, 1856 – Erasmus Augustine Kallihirua dies in St. John's". Nunatsiaq News. Archived from the original on December 5, 2023. Retrieved December 5, 2023.

- ^ a b Høvik & Jeremiassen 2023, p. 991.

- ^ a b c d e f Holland, Clive (1985). "Kallihirua". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. 8. University of Toronto. Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ a b c Høvik & Jeremiassen 2023, pp. 990–991.

- ^ a b c Malaurie 2003, p. 58.

- ^ a b Martin 2023, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Marsh, James H.; Beattie, Owen; de Bruin, Tabitha (March 8, 2018). "Franklin Search". Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ Snow 1851, p. 192.

- ^ a b Martin 2023, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Martin 2023, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Martin 2022, pp. 247–248.

- ^ Martin 2023, pp. 6–8.

- ^ Høvik & Jeremiassen 2023, pp. 977–978.

- ^ Martin 2023, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Snow 1851, p. 201.

- ^ Martin 2023, p. 13.

- ^ Høvik & Jeremiassen 2023, pp. 992.

- ^ Martin, Peter R. (2022). "The Cartography of Kallihirua?: Reassessing Indigenous Mapmaking and Arctic Encounters". Cartographica. 57 (3): 247–249. doi:10.3138/cart-2021-0012. S2CID 253661275.

- ^ a b Høvik & Jeremiassen 2023, p. 998.

- ^ Høvik & Jeremiassen 2023, pp. 992–993.

- ^ Martin 2023, p. 7.

- ^ a b Høvik & Jeremiassen 2023, p. 979.

- ^ Murray 1856, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Høvik & Jeremiassen 2023, p. 194.

- ^ Murray 1856, pp. 29–39.

- ^ Høvik & Jeremiassen 2023, pp. 994.

- ^ Murray 1856, pp. 36–39.

- ^ Høvik & Jeremiassen 2023, p. 981.

- ^ Murray 1856, p. 45.

- ^ Murray 1856, pp. 45–47.

- ^ Murray 1856, p. 51.

- ^ Høvik & Jeremiassen 2023, p. 978.

Bibliography[edit]

- Høvik, Ingeborg; Jeremiassen, Axel (February 9, 2023). "Traces of an Arctic Voice: The Portrait of Qalaherriaq". Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies. 25 (7): 975–1003. doi:10.1080/1369801X.2023.2169626. hdl:10037/30303. Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved January 10, 2024 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- Martin, Peter R. (July 14, 2023). "'Kalli in the ship': Inughuit abduction and the shaping of Arctic knowledge". History and Anthropology: 1–26. doi:10.1080/02757206.2023.2235383. Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved January 10, 2024 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- Malaurie, Jean (2003). Ultima Thule: Explorers and Natives of the Polar North. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-05150-6.

Primary sources[edit]

- Murray, Thomas Boyles (1856). Kalli, the Esquimaux Christian. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. Archived from the original on January 11, 2024. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- Snow, William Parker (1851). Voyage of the "Prince Albert" in search of Sir John Franklin. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. ISBN 978-0-665-40695-9.