Rakhi system

| Part of a series on |

| Sikhism |

|---|

|

The Rakhi system (Punjabi: ਰੱਖਿਆ; rakhi'a, rakhi'ā, rakhiaa; meaning "security")[1][2] was a tributary protectorate scheme practiced by the Dal Khalsa of the Sikh Confederacy in the 18th century.[3][4][5][6][7][8] It was alternatively called the Jamadari system.[9]

Background[edit]

Due to the invasions of Ahmad Shah Abdali, administration in the Punjab had broken down considerably and many bandits, "brigands", and "highwaymen" ran amok terrorizing and stealing from the local population.[10] The situation with the local government was no better; the poor administration of Mir Mannu's widow, Mughlani Begum, and the antics of Adina Beg, further worsened the local conditions in the land of five rivers.[8] The Mughal officials had become titular in their positions and had no real control or authoritative power anylonger.[8] Furthermore, the local economy was in tatters, revenue collection by officials had ceased to function, and powerful feudal lords, named zamindars, were exploiting the peasantry.[10] To meet the demand for authority in light of these circumstances, the Dal Khalsa dedicated one or more units to the cause.[10] Thus, the Rakhi system came into being.[11] The system officially began in the regions under Sikh-rule through the passing of a Gurmata pronouncement of the Sarbat Khalsa in the year 1753.[6] It was an improved replacement to the Chauth system.[3][12] Whilst the Chauth system of the Marathas offered civil administration and the deployment of its soldiers (often undesired) in a given area, it did not offer or guarantee the locals protection from foreign invaders or internal troublemakers, in-contrast to the Rakhi system which covered these areas as well.[8]

Purpose[edit]

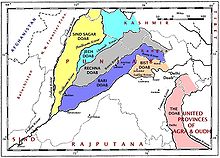

The Sardari in-which the Rakhi tax was paid to by the locals was obliged to protect them from "plunder, theft, or molestation" from within the community or by outsiders.[3][9] Folks from all backgrounds were afforded protection by the Khalsa through the Rakhi arrangement; from various religious backgrounds (such as Hindus, Sikhs, and Muslims) to various social classes (peasants and landowners).[11][8] The protectees had their physical lives, real-estate, and chattel under protection by the Khalsa.[8] In-practice, it acted effectively as a "parallel government" and constituted a large source of income for the Sikh Misls.[3][4] The system was popular amongst the Punjabi masses, who saw it as an alternative to the “cruel” Mughal governance that existed prior.[13] Eventually, four out of the five doabs of the Punjab were under the firm grip of the Rakhi system.[10][8] The Sikh leaders also constructed many fortresses during this time.[11] If an area paid the Rakhi tax to a Sikh chief, other groups of Sikhs would respect this agreement and not plunder or pillage the region, as they respected the Rakhi system's binding agreement between the local inhabitants and its protector.[12][8]

"By the end of the second half of the 18th century, many village clusters came under the Sikh protection. This system appears to have acted as a catalyst for the Sikhs to rise to position themselves in Punjab from being small-time chiefs to administrators and landlords, and finally to becoming rulers."

— Rishi Singh, State Formation and the Establishment of Non-Muslim Hegemony: Post-Mughal 19th-century Punjab (2015)

Mughals and Muslim Rajputs did not agree to come under the protection of the Sikhs nor pay the Rakhi so they were expelled from the areas they inhabited which came under Sikh control.[8] Those expelled often consisted of the people who had occupied the dwellings and properties of past Sikhs, who had fled in years prior in the face of oppression by the Mughal and Afghan empires.[8]

Adina Beg, the last Mughal governor of the Punjab, had paid the Rakhi tax, in an amount of 1.25 lakh (125,000) rupees for the Jalandhar Doab, as a reward to the Sikhs for helping him earlier.[8] He also distributed karah parshad worth 1,000 rupees during festivities.[8]

Payment[edit]

The payment amounted to one-fifth of the revenue of the grains produced by a locality at each harvest (every harhi and sauna, or every rabi and kharif harvest)[8] or one-fifth of their income.[1][10][11] This sum or tribute was gathered by the village headman and paid twice a year to the local Sikh chief whose jurisdiction it belonged to.[12] feudal lords (zamindars), tradesmen, and merchants paid the Rakhi tax, whilst artisans paid a different tax known as Kambli (meaning "blanket-money") which was on-average equal to the price of a blanket.[12][14]

See also[edit]

- Gurmata, a term used to refer to resolutions passed by the Sarbat Khalsa

- Sarbat Khalsa

- Hukamnama, an injunction or edict issued by the Sikh gurus, their officiated followers, the Takhts, or taken from the Guru Granth Sahib

References[edit]

- ^ a b Shri, Satya (2017). Demystifying Brahminism and Re-Inventing Hinduism. Vol. 2 Re-Inventing Hinduism. Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India: Notion Press. ISBN 9781946515568.

- ^ Shabdkosh.com. "ਰੱਖਿਆ - Meaning in English - ਰੱਖਿਆ Translation in English". SHABDKOSH. Retrieved 2023-03-07.

- ^ a b c d Bhagata, Siṅgha (1993). A History of the Sikh Misals. Publication Bureau, Patiala Punjabi University. pp. 44–50.

- ^ a b Gopal Singh (1994). Politics of Sikh homeland, 1940-1990. Delhi: Ajanta Publications. pp. 39–42. ISBN 81-202-0419-0. OCLC 32242388.

- ^ Johar, Surinder Singh (2002). "7. The Rakhi System and After". The Sikh Sword to Power. Arsee Publishers. pp. 85–93.

- ^ a b Ahluwalia, Jasbir Singh (2003). Liberating Sikhism from 'the Sikhs': Sikhism's Potential for World Civilization. Chandigarh, India: Unistar Books. p. 85.

- ^ Chhabra, G.S. (2005). Advanced Study in the History of Modern India. Vol. 1: 1707-1803 (Revised ed.). New Delhi, India: Lotus Press. p. 43. ISBN 9788189093068.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Singh, Sardar Harjeet (2009). Faith & philosophy of Sikhism. Delhi, India: Kalpaz Publications. pp. 18–21. ISBN 978-81-7835-721-8. OCLC 428923087.

- ^ a b Gandhi, Surjit Singh (1980). Struggle of the Sikhs for Sovereignty. Gur Das Kapur. pp. 168–169, 288.

- ^ a b c d e Lafont, Jean Marie (2002). Maharaja Ranjit Singh - First Death Centenary Memorial. Atlantic Publishers & Distri. pp. 63–64.

- ^ a b c d A history of modern India, 1480-1950. Claude Markovits. London: Anthem. 2004. pp. 199, 571. ISBN 1-84331-152-6. OCLC 56646574.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c d Singh, Rishi (2015). State Formation and the Establishment of Non-Muslim Hegemony : Post-Mughal 19th-century Punjab. New Delhi: SAGE Publications. ISBN 93-5150-504-9. OCLC 1101028781.

- ^ Saggu, Devinder Singh (2018). Battle Tactics and War Manoeuvres of the Sikhs. Notion Press. ISBN 9781642490060.

- ^ Kolff, D. H. A. (2010). Grass in their mouths : the Upper Doab of India under the Company's Magna Charta, 1793-1830. Vol. 33 of Brill's Indological Library. Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill. pp. 455–456. ISBN 978-90-04-18802-0. OCLC 714838726.