Sonya Noskowiak

Sonya Noskowiak | |

|---|---|

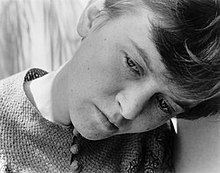

Sonya Noskowiak, c.1932. Photograph by Imogen Cunningham. | |

| Born | November 25, 1900 Leipzig, Germany |

| Died | April 28, 1975 (aged 74) Greenbrae, California, US |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Photography |

| Partner | Edward Weston (1929–1935) |

Sonya Noskowiak (25 November 1900 – 28 April 1975) was a 20th-century German-American photographer and member of the San Francisco photography collective Group f/64 that included Ansel Adams and Edward Weston. She is considered an important figure in one of the great photographic movements of the twentieth century. Throughout her career, Noskowiak photographed landscapes, still lifes, and portraits. Her most well-known, though unacknowledged, portraits are of the author John Steinbeck. In 1936, Noskowiak was awarded a prize at the annual exhibition of the San Francisco Society of Women Artists. She was also represented in the San Francisco Museum of Art’s “Scenes from San Francisco” exhibit in 1939. Ten years before her death, Noskowiak's work was included in a WPA exhibition at the Oakland Museum in Oakland, California.

Life[edit]

Early life[edit]

Noskowiak was born in Leipzig, Germany. Her father was a landscape gardener who instilled in her an awareness of the land that would later become evident in her photography.[1] In her early years, she moved around the world while her father sought work in Chile, then Panama, before finally settling in Los Angeles, California, in 1915. In 1919, she moved to San Francisco to enroll in secretarial school.[2] Interested in photography from an early age, in 1925, at age 25, Noskowiak became a receptionist in Johan Hagemeyer's photographic studio in Los Angeles County. Upon expressing her interest in photography to him, Hagemeyer wrote off her dream as a joke in his diary.

Becoming a photographer[edit]

In early April 1929, Noskowiak met photographer Edward Weston at a party, and the two began a relationship immediately; she eventually became his model, muse, pupil, and assistant. Weston first taught her to "spot' photos——touching up flaws in prints——before giving her her first professional camera. This camera contained no film, and for several months Noskowiak worked with Weston, pretending to photograph while he taught her the mechanics of photography. During her time with Weston, Noskowiak's photography developed greatly, suggesting her understanding of craftsmanship as well as expressing her own style. Several of Weston's works, such as Red Cabbage Halved and Artichoke Halved, were inspired by Noskowiak's early negatives. Weston once said: "Any of these I would sign as my own." Dora Hagemeyer (sister-in-law of Johan Hagemeyer) wrote that while Noskowiak's photographic style was clean and direct like Weston's, she "put into her work something which is essentially her own: a subtle and delicate loveliness."[3]

Group F.64[edit]

Art photography in the late 1800s and early 1900s was defined by pictorialism, a style that refers to a photographer's manipulation of an otherwise straightforward photograph as the means of 'creating' the final work. This was in response to claims that photography was not an art but merely scientific or mechanical documentation.[4] Weston and other photographers began to turn away from pictorialism, with many having growing concerns about their place in photography. In 1932 Noskowiak became an organizing member of the short-lived Group f/64, which included such important photographers as Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, and Willard Van Dyke, as well as Weston and his son Brett. Noskowiak's works were shown at Group f/64's inaugural exhibition at San Francisco's M. H. de Young Museum; nine photographs of hers were included in the exhibit – the same number as Weston.[5] .[5]

Early success[edit]

In the summer of 1933, Noskowiak, along with Weston and Van Dyke, traveled to New Mexico to photograph the scenery. Her photographs Cottonwood Tree - Taos, New Mexico, and Ovens, Taos Pueblo, New Mexico were taken on this trip and differ from her previous work. Cottonwood Tree is not nearly as intimate as her other works, while Ovens is the earliest of her work to focus on human-made culture. Later that summer, she had her first solo show at Denny-Watrous Gallery in Carmel. The exhibition included a series of photographs from New Mexico. She had another solo exhibition at 683 Brockhurst in November. Between 1933 and 1940, she participated in a few of Group f/64 exhibitions, including shows such as those at the Fine Arts Gallery in San Diego, Fresno State College, and the Portland Art Museum in Oregon.

Group F/64 dissolvement[edit]

Noskowiak and Weston broke up in 1935, and Group f/64 disbanded shortly thereafter—perhaps because of her frayed relationship with Weston and perhaps because other members of the group were going their separate ways.[6] Although Noskowiak's writing began to diminish during this time, her photographic career did not. Noskowiak moved to San Francisco and opened a portrait studio that year on Union Street. In 1936, she was one of eight photographers, including Weston, selected from the California region of the Federal Art Project to document California during the Great Depression.

Commercial work[edit]

Noskowiak also engaged in commercial work and commissions to make a living. After Group f/64 dissolved, she spent the next year photographing California artists and their paintings, sculptures, and murals. These images then toured to a variety of public institutions. Though she continued to photograph as an artist, Noskowiak's livelihood from the 1940s on was based on portraiture, fashion and architectural images. Noskowiak photographed many prominent figures such as painter Jean Charlot, dancer Martha Graham, composer Edgard Varèse, teenage violinist Isaac Stern, and writers Langston Hughes and John Steinbeck.[2] The portrait of Steinbeck is particularly powerful and is one of only a handful of images of the writer in the 1930s. It is still used extensively to represent him.[7] She continued commercial photography up until the 1960s, photographing images for manufactures of lamps and stoves, as well as for architects.

Photography[edit]

Noskowiak primarily focused on landscapes and portraits between the 1930s and 1940s. Noskowiak embraced straight photography and used it as a tool to give newer meaning to her photographs. She emphasized the forms, patterns, and textures of her subject, to enrich the documentation of it.

Her earliest works reflect the work of photographers of her period and their thoughts on pictorialism. In her earliest works, such as City Rooftops, Mountains in Distance (the 1930s), there is a graphic quality to how she abstracted the piece. There is the dark, strong industrial structure that contrasts with the light sky. There are almost no logs seen on the buildings, as if they are they are blurred beyond readability. This is an example of the 'New Objectivity' movement, which focused on a harder, documentary approach to photography.

Noskowiak often composed her photographs to intersect her subjects, which gave a more dynamic feel to her photographs. Examples of these are provided by her works Kelp (1930) and Calla Lily (1932). The composition crops the boundaries of the kelp plant and flower and draws the viewer's eye to the texture of the plants. The kelp is so abstracted that if not for the title it would be unrecognizable. In Calla Lily, her use of chiaroscuro gives a luminous, almost floating feeling to the photograph.

Her photograph Agave (1933) is an intimate viewing of the cactus plant—another example of a composition separating the object from what is made visible shown and emphasizing the plant's beautiful pattern.

Noskowiak utilized the same technique of straight photography in her pictorial portraits and commercial works. The same intimacy shown in Agave can be seen in portrait works such as John Steinbeck (1935) and Barbara (1941). In both, she creates an intimate atmosphere, in which the viewer feels as though they are there interacting with the subjects. Even in her more commercial works, Noskowiak's style and technique still remained important. In her untitled 1930s photograph, you have a model with a broad-brimmed hat that conceals her face. The composition of the piece relieves viewers from thinking about the photograph as an advertisement. The cropping and position of the model offers closeness, and viewers get the feeling of being in the moment with the model more than simply responding to the photo as an advertisement.

Noskowiak's legacy[edit]

In 1965, Noskowiak was diagnosed with bone cancer, and she ended her photographic work. She lived another ten years before passing away on April 28, 1975, in Greenbrae, California. It is hard to say what legacy Noskowiak left behind, as the discussion of her work began to dwindle after her breakup with Weston; nevertheless, some observers, such as Richard Gadd, the director of the Weston Gallery in Carmel, who believe that Noskowiak forged a path for young photographers. In recent years, Noskowiak's work has been included in group shows at the Weston Gallery, the Oakland Museum in California, and the Portland Museum of Art in Maine.

In 2011, thirty-six years after her death, Noskowiak shared an exhibition with Brett Weston at the Phoenix Art Museum. In 2015, eight of Noskowiak’s works were on view at the Allentown Art Museum in Pennsylvania. The exhibition, named Weston's Women, however, acknowledges Noskowiak and other female artists only in their relation to Weston. Her archives, including 494 prints, hundreds of negatives, and many letters to Edward Weston, are now housed at the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, Arizona.

Notes[edit]

- ^ Darsie Alexander (2002). Original Sources: Art and Archives at the Center for Creative Photography. Center for Creative Photography. p. 149.

- ^ a b Marnie Gillett (1979). Sonya Noskowiak. Center for Creative Photography. p. 4.

- ^ Hagemeyer, Dora (8 September 1933). "Noskowiak Exhibit Important to Art". Carmel Pine Cone: 4.

- ^ Paul J Karlstrom (1996). On the Edge of America: California Modernist Art. University of California Press. p. 246.

- ^ Therese Thau Heyman (1992). Seeing Straight: The f.64 Revolution in Photography. Oakland Museum. p. 67.

- ^ Donna Bender (1979). Sonya Noskowiak Archive, Guide Series 5. Center for Creative Photography. p. 5.

- ^ Krim, Arthur (2018). ". "John Steinbeck and Sonya Noskowiak: Dating the Iconic Photo."". The Steinbeck Review: 187.

Further reading[edit]

- Rosenblum, Naomi (2014). A history of women photographers. New York: Abbeville. ISBN 9780789212245.

- University of Arizona. Center for Creative Photography.; Phoenix Art Museum. (2007). Debating modern photography : the triumph of Group f/64. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona. p. 8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links[edit]

- Nude, 1934. Sonya Noskowiak by Edward Weston

- University of Arizona Center for Creative Photography: patterns by Sonya Noskowiak