St. Christopher's Church (Reinhausen)

St. Christopher Church is the Protestant-Lutheran parish church located in the village of Reinhausen in the district of Göttingen, Lower Saxony. The church stands on the sandstone rock of the Kirchberg above the village center. It was originally built as a castle chapel by the Counts of Reinhausen in the 10th century and later served as a church for the collegiate monastery and the Benedictine monastery of Reinhausen that emerged from it in the 12th century. The church in Reinhausen, commonly known as the Reinhausen monastery church, has served as the parish church of the village of Reinhausen for many years. Following the introduction of the Reformation in 1542, the monastery was gradually dissolved, and the church was then solely used as a parish church, with brief interruptions. Today, it belongs to the Göttingen church district in the Hildesheim-Göttingen branch of the Hanoverian regional church.

Despite significant structural changes in the Gothic and Baroque styles, the overall appearance of the Romanesque monastery church remains prominent. This is especially evident in the west facade with its double tower. The building type underwent several construction phases, transforming from a Romanesque basilica to a hall church. The interior of the church contains several late medieval works of art, such as two late Gothic altars, extensive remains of wall paintings, and stone sculptures depicting St. Christopher, the patron saint of the church.

Location[edit]

The monastery church is situated at an altitude of approximately 210 meters above sea level on the Kirchberg. It is located about 30 meters north of a cliff edge that drops steeply down to the valley of the Wendebach stream and the village center of Reinhausen, which is situated in the valley to the southeast of the church.[1] The church's location on a spur of the Knüll, which extends to the west and rises steeply above the village, makes it highly exposed.[2] In contrast to the village center, the location is visible from the adjacent hills to the west and even from the western slope of the Leinetal valley.

Access to the church from the village was only possible on foot via three steps carved into the rock until the early 19th century. The road leading from the village to the church hill was built during this time. The steps are now very worn out.[3] Carts could only access the church from the north-east via State ownership.[4]

The church is oriented at an angle of approximately 23 degrees to the north, but its truthfulness is not relevant to this description.[5] The west wing of the church faces west-southwest and borders a paved parking lot where the current access road ends. The terrain slopes significantly to this side. To the west of the church, there is a former school and the village kindergarten located on a spur of the Kirchberg. The churchyard is enclosed, with the south and east sides bordering it, while the north side is not accessible to the public. It is adjacent to the former monastery grounds, which now house the Reinhausen forestry office in the former office building,[5] separated from the churchyard by a sandstone wall. Unfortunately, the intermediate building that connected the west front of the church with the Amtshaus was destroyed by fire in 1955, leaving only the outer walls of the two massive basement levels.[6] The Reinhausen estate is located to the northeast of the cemetery.[3]

History[edit]

Castle of the Counts of Reinhausen[edit]

The Reinhausen Kirchberg's oldest archaeological evidence of human activity is a fragment of a stone axe from the Neolithic period.[7] However, continuous settlement was not evident until the early Middle Ages. Beginning in the 9th century, the Counts of Reinhausen had a castle complex on the spur of the mountain above the village of Kirchberg, which was naturally protected by rockfalls towards the valley. Numerous archaeological discoveries from the vicinity of the monastery church have been dated to the 9th and 10th centuries.[8] During the 10th and 11th centuries, the Counts of Reinhausen held the office of Count of Leinegau and were therefore of supra-regional importance.[9] Their ancestral castle in Reinhausen was accordingly sizable. The residential area with the church in the west covered approximately 1.5 hectares, while the adjoining farmyard to the northeast covered an additional hectare. The current location of the church, churchyard, and adjoining areas were included. Since 1980, smaller areas of the castle grounds have undergone archaeological investigation through several individual excavations and surveys.[8] A double-shell fortification wall, up to 3.30 meters thick, was discovered along a nine-meter stretch at the edge of the spur. The wall was demolished in the 12th century, as evidenced by small finds from the High Middle Ages in the building remains and demolition debris.[10] Towards the gently rising slope, the fortification comprised two section ditches and a three-meter-thick mortared wall. Reconstructing the interior of the castle is challenging due to the site being built over by the monastery in the High Middle Ages.[9] Excavations inside the monastery church revealed remains of the castle church of the Counts of Reinhausen.[8] However, the exact structural design of the castle church remains unknown.

Collegiate church[edit]

At the end of the 11th century, the Counts Konrad, Heinrich, and Hermann von Reinhausen and their sister Mathilde converted their ancestral castle into a monastery.[11] However, the dating of the conversion to a monastery to the year 1079 in older literature[12] is contradicted by more recent research.[11] Instead, based on possible dates of death of one of the founders, Count Konrad von Reinhausen, the years 1089 or 1086 are assumed as the latest date of foundation.[13] According to the historical building research by Ulfrid Müller in the years 1963-1967, it is considered certain that the building substance of the private church was used for its church after the castle was converted into a collegiate church and later into a monastery. This is indicated, among other things, by the design of the southern choir wall.[14] Thus, the layout of the castle church in the Ottonian period can be seen as the basic concept of the later collegiate church. The southern wall of the choir, with a still recognizable added arched window, its northern wall, the choir arch with imposts emphasizing the lower base of the arch, and the lower parts of the pillars in the nave are considered to be the remains of the castle church.[15] Ulfrid Müller assumed that the original church had a west portal, on the site of which the present tower front was later built.[16] Compared to other castle chapels in the region, the church is unusually large, reflecting the regional supremacy of the Counts of Reinhausen in the 10th and 11th centuries.[17]

The monastery church of Reinhausen thus goes back to a proprietary church in the noble castle of the Counts of Reinhausen, which has been archaeologically documented at this location since the 10th century.[18] Accordingly, the construction history of the church can be dated back to the 10th century.[19] Despite the lack of written evidence from the early period, it is almost certain that the church has a history of over a thousand years. Müller's research initially suggested that the castle church was built in the 11th century.[17]

Monastery church[edit]

Like the pre-monastic history, the early history of Reinhausen Monastery is mainly known from a report written by Reinhausen's first monk, Reinhard, between 1152 and 1156.[20][13] The transformation from a monastery to a convent was probably a process that took several decades.[21] The consecration of the monastery church is dated between 1107 and 1115 and was performed by Bishop Reinhard of Halberstadt.[22] Reinhausen belonged to the archbishopric of Mainz, so the consecration of the church was the responsibility of the archbishop of Mainz. Since the archbishopric of Mainz was vacant after the death of Bishop Ruthard and before the consecration of Adalbert, an external, neighboring bishop was commissioned to perform the consecration. Count Hermann of Winzenburg, the initiator of the foundation of the monastery, had hoped for a generous donation from Bishop Reinhard, but this was not granted.[21] In the Lower Saxony Monastery Book, the probable date of the consecration is assumed to be December 3, 1111.[22] The information about the consecration of the monastery most likely refers to the consecration of the monastery church, since the appointment of an abbot took place in 1116 at the earliest.[21]

The appearance of the monastery church can be roughly reconstructed for the first half of the 12th century. Ulfrid Müller and Klaus Grote, based on the results of their architectural research, assume that this form of the castle and collegiate church can also be assumed for the original building of the monastery church, i.e. that major alterations took place only after the monastery had already existed for some time.[15][12] Although the church was unusually large for a castle chapel, it was and is very small compared to other Romanesque monastery churches. There is almost no evidence of architectural ornamentation in the building fabric from the oldest monastic period, and the church was not vaulted - unlike the church of Lippoldsberg Monastery, which was an architectural pioneer in the region and was built in the mid-12th century.[23] This suggests that the church was built much earlier.[17] Parts of this first monastery church have been preserved in the north and south walls of the chancel, possibly[18] in the chancel arch including the crossbeams, in the eastern pair of pillars, and in the lower half of the two western pillars that stand in the central nave of the present church.[12] According to reconstructions, the church was a pillar basilica with a cruciform floor plan.[24] It had a transept that extended north and south beyond today's outer walls and a central nave that was raised above the aisles and lit by clerestories above the aisles.[18] The transept, with its strong architectural crossing, could have been built in the same way as the front part of the nave, which corresponds to it today, but the floor level was raised by three steps compared to the nave so that the floor level of the nave was correspondingly lower.[18] The aisles were separated from the transept by a wall - probably with an opening - the foundations of which were found on the south side of the church. According to the foundation finds, the eastern pillars of the central nave originally had a cruciform floor plan.[17] There is no information about the design of the western front of the first monastery church[18], such as a tower or a westwork; the present Romanesque western building is more recent. However, according to the report of the first Abbot Reinhard on the history of the Reinhausen monastery, the monastery was moved from the south side to the north side and extended due to lack of space, contrary to the plan of the monastery. This information may refer to the monastery church, as there is only about 10 meters of space south of the church to the cliff.[17] During its time as a monastery church, several alterations were made, chapels were built and added, and altars were donated.

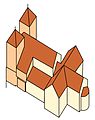

- Construction phase reconstruction according to Ulfrid Müller

-

Original building

-

12th century

-

End of the 13th century

-

14th century

-

17th century

-

Around 1800

The Romanesque west façade with its two towers, which is the most distinctive feature of the exterior, was built around 1170.[25] The mid-12th-century alterations were probably influenced by Abbess Eilika von Ringelheim, who came from the family of the Counts of Reinhausen and spent several months a year at her former ancestral seat in Reinhausen Abbey.[16] The steep slope of the terrain did not allow for a portal in the west façade, so the entrance for visitors not coming from the monastery was moved to its present location in an intermediate bay on the south side to the east of the tower. The entrance from the monastery area was on the opposite side of the north wall.[16] Opinions differ as to whether a gallery was already built into the central building when the west transept was constructed: Ulfrid Müller suggests that a gallery was almost certainly present since it could have served as a gallery for the Abbess and Countess Eilika, allowing her to attend services in the monks' church in the manner of a nun's gallery. Furthermore, there is a connection between the later wall paintings and the northern access to the gallery from the upper floor of the monastery building.[16] Tobias Ulbrich does not necessarily see these references and disputes the compelling dating of a gallery system to the time before 1400.[25] In addition to the clerestory windows, the nave was lit by two large arched windows in the west transept, which were later altered and reconstructed in 1893.[16]

The clear protrusion of the side aisle foundation on the inside leads to the assumption that the side aisles were widened slightly in the second half of the 12th century. Based on the walled-up arched windows and the interior paintings, it can be determined that they were three-quarters as high as they are today.[25] The new walls of the side aisles were constructed with greater thickness. Their thickness, similar to that of the west transept, is approximately 1.30 meters, while the older walls are only approximately 90 centimeters thick.[16] Ulfrid Müller also postulates that the central nave was significantly elevated during this construction phase,[26] yet this theory is contested by others.[25] The separated crossing remained unaltered during the late Romanesque construction phase.[16]

A renewed economic upswing at the monastery between 1245 and 1309 brought with it new construction work on the monastery church.[27] In a Mainz indulgence document of 1290, Archbishop Gerhard II of Mainz granted a forty-day indulgence[28] to anyone who contributed to the construction of the Reinhausen church.[29] At the end of the 13th century, the northern and southern bays of the west transept and the two adjoining intermediate bays were given a simple groined vault, the belt arches of the lower tower floors were redesigned as pointed arches, as were the arches on the east side of the first upper floor in the tower. The main entrance on the south side lost the tympanum that had originally filled the vaulted field of the round-arched portal and received a pointed arch doorway.[27] On the south side, west of the transept, a second portal, now closed, was broken in.[27]

During the same construction period, a chapel of Saint Maurice with three Gothic lancet windows was built above the entrance on the south side of the church.[28] The chapel of St. Maurice extended over two bays and the wall of the side aisle was raised for the chapel at this point.[29]Access was through the gallery. Due to the size of the chapel room, the east wall was not on the axis of the existing pillar, but one meter east of it. The wall on the first floor was supported by a wall directly below it, creating a separate entrance hall under the chapel. The altar of St. Maurice's Chapel had its brick foundation, visible as a column in the northeastern corner of the vaulted entrance hall.[27] The altar, and thus the chapel, was first documented in 1415 on the occasion of the establishment of a mass for the souls.[30] According to the Göttingen chronicler Franciscus Lubecus, another chapel was built by Abbot Gunter von Roringen before he died in 1300 as a burial place for the abbots of Reinhausen monastery. This dating is questionable because Gunter was still abbot of the monastery in 1382 and 1385.[31]

During the renovation works in 1965, the beginnings of a rib vault were found to the north of the choir, in the area of the sacristy built there.[32] It belonged to a Gothic side chapel with a 3/8 end.[26] There was a narrow corridor between the northern arm of the transept and the chapel, which provided direct access to the choir from the monastery building.[27] The remains of the chapel are related to the chapel to the north of the choir, which was mentioned in a document in 1394 and served as the burial place of the Lords of Uslar.[33] It is also called St. John's Chapel because tradition mentions it as the site of an altar dedicated to St. John the Evangelist: A new altar in the ambulatory is mentioned in writing in 1360, a burial place for the knight Ernst of Uslar in front of the altar of St. John the Evangelist in 1378, and a donation by the four sons of Ernst of Uslar for the altar of St. John in the new chapel in the ambulatory in 1399.[34] The Uslar burial chapel is still listed in the inventory of 1707.[29] Older literature dates the chapel to 1322.[27][29] The dating is based on two damaged keystones of a ribbed vault with inscriptions that were found in the area in the 19th century and attributed to this chapel.[27] They are now kept in the Maurice Chapel.[29] The recent deciphering of the inscriptions "•an(n)o•1•5•22•d(omi)n(u)s•m[at]hias• […]" and "frater•reÿnerus•prior•", which differs from the earlier reading, argues against this early dating of the keystones.[35] The attribution of these keystones to the burial chapel of the Lords of Uslar is therefore no longer probable, and the dating of this chapel to 1322 is no longer valid.[33]

According to recent findings, the passage from the northern bay of the church to the southwestern corner of the adjacent cloister was walled up from the inside already in the Middle Ages. On the outside, a niche was created, the lower part of which was later also walled up. Four Gothic tracery tiles were found under a layer of humus during drainage works in 1993. Neither in the adjacent area of the cloister nor in the area of the door threshold under the medieval wall was there any continuation of the tiling or any evidence of it.[36] Hildegard Krösche thinks that these tiles belong to the chapel north of the choir.[37]

From the beginning of the 14th century until the dissolution of the monastery in 1574, construction work was mainly devoted to the decoration of the church and its chapels. Between 1387 and 1442, the interior walls were decorated with murals, at least in the entrance hall, on the side walls of the gallery, and in the southern aisle. After the Reinhausen monastery joined the Bursfelde Congregation in 1446, more late Gothic furnishings were donated.[38] The last written donation specifically for the construction of the church and monastery was made by the Lords of Uslar in 1451. In 1498 and 1507 a late Gothic carved altar was donated, large parts of which are still preserved today.[39] According to a recent reading of the inscriptions on the two keystones in the Maurice Chapel, it is likely that a major expansion or rebuilding of the monastery took place in 1522, and that a vault was added to one of the buildings.[33] This could also be indicated by the inscription on a stone,[40] now lost, which was set into the cemetery wall as a spolia in the 19th century: "M.ccccc.xxii. / S.georivs ora pro nobis."[41] ("1522 / St. George (?), pray for us.")

Since the Reformation[edit]

Even before the Reformation, the monastery was already in a downward economic and personnel trend,[42] which was accelerated by the introduction of the Reformation in 1542 and the establishment of a manor house on the monastery grounds. 20 years after the introduction of the Lutheran monastic order, the inventory of the monastery and the church was listed because the monastery was to be handed over to Ludolf Fischer, who was appointed bailiff.[43] The last monk of the old monastery died in Reinhausen in 1564.[44]

The further reconstruction of the church building after the dissolution of the monastery can be seen only in the first pictorial representation on an engraving by Matthäus Merian, published in 1654 in the Topographia Germaniae. At that time, the basilica form was no longer recognizable from the outside.[45] The transept was combined with the transept, choir and nave under a gabled roof.[28] The towers were crowned with high pointed spires[28] and there was also a ridge turret on the choir. This is confirmed by an inventory of the monastery from 1707, which mentions a bell above the choir.[38]

At the beginning of the 18th century, the cruciform floor plan was abandoned by demolishing the transept walls and building the side aisle walls in a continuous line. The east wall of the choir was rebuilt with old stones and received a large Baroque window, and large Baroque window openings were also made in the side aisle walls.[28] The western facade also received a Baroque window.[45] A shortening of the church reported by Mithoff in 1861, which is said to have taken place 150 years earlier, will refer to these measures.[46] The basilica was fundamentally transformed into a hall church by installing a lower ceiling over all the naves.[47]

In the years 1885-1887, extensive renovations were carried out, during which the connecting floor between the towers was reconstructed.[24] The western gallery was also rebuilt,[26] the dormers were removed, and the roof was constructed without the previous cornice.[45] In addition, after the removal of the Baroque pulpit-altar wall, the church received a winged altar made of the remains of the medieval altar of the Virgin Mary and supplemented with new parts, which have served as the main altar ever since.[28] To protect the walls of the choir from moisture, a second wall was built in front of the lower part of the walls.[48] Another fundamental restoration of the church interior took place between 1963 and 1967 when a sacristy and a boiler room were added to the north of the choir.[28] During the reconstruction and renovation of the church, archaeological excavations were carried out between 1965 and 1968, and the existing structure of the church was precisely measured and examined by Ulfrid Müller.[32] Since the building history research began long after the reconstruction work began, no further excavations could be carried out in the western part of the church.[38] Therefore, it was not possible to obtain information about a possible tower or a differently designed western end of the original church building.[49] The façade of the tower was renovated in 1990/1991.[50]In February 2011, the Church Building Society St. Christopher Reinhausen Association was founded to raise funds for the maintenance and renovation of the church.[51][52]

Architecture[edit]

External construction[edit]

The appearance of the monastery church is dominated by the monumental Romanesque double-tower façade on the west side.[24] Built of locally quarried buntsandstein blocks of low strength,[4] it is divided, apart from narrow window openings that hardly disturb the unity of the overall impression, only by a very narrow, simple cornice at the base.[24] The total width of the west building is 16.30 meters.[26] The towers end with low-hip roofs with transverse ridges, giving them a somewhat squat appearance, especially when viewed from a distance. The roof of the south tower is slightly lower than that of the north tower. Under the roofs, the sound openings are arranged as mullions whose Romanesque dividing columns have cube capitals and attic bases.[24] The masonry of the towers rises 5.50 meters above that of the central wing, between them lies the sloping roof of the nave roof, which slopes down to the west. The 5.75-meter-high upper story is divided into two stories below the towers, which are lit at the top by a slightly wider arched window with a central pillar and a single narrow arched window below.[53] Only the upper story between the towers, which was reconstructed during a major renovation at the end of the 19th century, has two significantly larger arched windows.[24] On the first floor of the west façade, there are another four arched windows, each 45 centimeters wide and 1.40 meters high.[53] A door is broken into the base of the south tower under the southern of these windows.[26]

The simple basic form of today's appearance over a longitudinal rectangular floor plan looks like that of an aisleless church or simple hall church. With a length of 28.60 meters, excluding the choir, the church is significantly smaller than other monastery churches in the region.[12] The entire building is unplastered on the outside. The simple gable roof with a continuous ridge and the hip roof over the tower connecting floor and over the choir emphasize the simplicity of the building's form.

The Romanesque main portal on the south side, just behind the western transom, is particularly striking, projecting slightly from the building line; the projecting wall section is slightly rectangular, finished and emphasized at the top by a simple cornice,[24] the portal is not in the middle, but clearly offset to the left. The sandstone ashlar masonry next to the protruding portal zone is attached to the masonry of the tower without a building seam.[54] The round-arched portal itself is characterized by several stepped jambs and laterally placed columns with cube capitals and an attic base; the transition from the lateral portal jambs to the high arched field above the portal is designed as a profiled impost zone.[24] The innermost jamb, on the other hand, has a smooth transition from the transom zone and a slightly pointed arch. The Gothic lancet windows, which belong to the Maurice Chapel above the entrance hall, are arranged in close proximity at a slight distance above the portal. The outer wall area of the chapel is constructed from coarsely hewn sandstone blocks, with only large-format and carefully smoothed stones present on the originally exposed eastern edge.[28] The larger stones of the Maurice Chapel exhibit pincer holes, in contrast to the ashlars on the older west transom and in the portal zone. On the north side of the church, opposite the Moritz Chapel and portal zone, one wall area has a mixed masonry structure. Only the upper part of a walled arched door, measuring 82 centimetres in width, is still visible. This originally provided a direct passageway between the church and the cloister. Another, now walled-up arched door on the north side led from the upper floor of the cloister to the second floor of the tower.[55]

To the east of the portal zone, the south wall of the nave is predominantly of roughly hewn sandstone, with the eastern section, about 7.50 meters wide, bounded by a building seam and where the transept was located until the beginning of the 18th century, having an even more irregular stone setting and less surface treatment.[56] In the southeastern corner of the nave, the usual careful corner ashlar work is missing because the former transept was demolished at this point.[32] The three baroque arched windows are approximately 2 meters wide and 3.35 meters high.[56] They are framed by simple but carefully carved stone surrounds of red and light sandstone, with the lintels and keystones projecting slightly from the rest of the jambs. The window openings on the south wall correspond to the opposite ones on the north wall, although the eastern window has been reduced in height in favor of a door to the former monastery courtyard below.[55] Between the western and the central window of the south wall, the strongly chamfered jambs of a much smaller, simple arched window from the Romanesque period, which was later walled up, are clearly visible.[56] This former window also corresponds to a bricked-up window of the same size in the northern wall of the church.[55] On the left, below the central window of the southern wall of the nave, the jambs of a small ogival door, also walled up, can be seen; the only decorative feature is a simple chamfer on the edge of the jamb.[56] The east wall of the south aisle and the side walls of the choir are now windowless. There is only a wooden hatch above the edge of the side aisle roof.

The recessed eastern choir, 6.40 meters deep and 7.30 meters wide,[26] with a straight end, has small, regular layered stone wall on the south wall, which differs from the less regular layered masonry on the east end of the aisles and on the east wall of the choir.[24] A small Romanesque window, now closed, can also be seen in the south wall of the choir. The masonry of the northern choir wall above the later extension is similar to that of the southern wall.[32] These choir side walls date from the time of the church's construction.[17] Wide, unadorned buttresses are attached to the outside corners of the choir. The fact that this is a later addition can be seen in the seam between the wall and the choir and in the ashlars that run through the wall. In the Baroque eastern choir wall, as well as in the eastern end of the aisles, which were altered at the same time, there are reused stones from older construction phases. They can be recognized by their profiling or pincer holes and were reworked with a pointed chisel for reuse. A Baroque window in the middle of the eastern wall of the choir corresponds in its design to the windows of the side aisles. On the north side of the choir, there is a low extension built in 1965 during the renovation of the church for the heating system and the sacristy.[32] Its walls are also faced with sandstone. To the east of the sanctuary, a retaining wall was built to prevent the ground from rising to the east and north of the sanctuary, creating a trench towards the sanctuary. In the area of the heating extension, this trench is about 1.80 meters deep,[32] so that only the roof of the extension is visible from the cemetery. To the north of the extension is an old sandstone wall that shows the consoles of a former cross-ribbed vault and the lower bases of the ribs facing the pit. Above the extension, the wall separates the church property from that of the Forest Service. The eastern extension of the wall, built later, forms the retaining wall of the cemetery.[32]

The north side of the church abuts the neighboring property and is not visible to visitors. After a fire in April 1955, only the west wall of a former forestry office building attached to the north side of the west wall of the church remains, aligned with the lower west wall of the church.[55]

Interior[edit]

The interior of the church is divided into a western and an eastern section. The entrance is through a small hall with a painted ogival vault in the south of the western part of the building.[28] From there, a door leads to the west to the south tower and the staircase to the upper floors, to the north to the community room, and to the east to the actual interior of the church, which is three steps higher.[48]

The main eastern section of St. Christopher's is a brightly plastered, three-aisled hall with a flat, unadorned wooden ceiling.[28] The interior is 7.10 meters high and the central nave is 5.50 meters wide. The side aisles are each 3.50 meters wide, although the north aisle narrows to 2.70 meters due to the considerably thicker wall of the north wall in the central area. The aisles are separated from the central nave by two rectangular piers, each of which supports round-arched arches above narrow arcades that are wide in relation to the dimensions of the church interior. The span of each of the three bays is just over five meters.[48] The pillars stand on the floor without bases. The two eastern pillars - originally the crossing pillars at the western beginning of the transept - each have a base area of 87 centimeters wide and 1.60 meters long, and a much more elongated cross-section than the western pair of pillars, which are the same width but only one meter long. The transition from the piers to the arches is accentuated by profiled transom plates with circumferential corrugations and fillets, which are further accentuated by a color scheme that matches the red sandstone against the white plaster. The large Baroque windows in the side aisles and the choir are glazed with small clear panes between wooden mullions. The internal jambs of the window niches end with segmental arches and are slightly sloped, while the window sills are strongly sloped. The added door and window jambs from earlier phases of construction, visible on the exterior, are not visible on the interior; on the south wall, this is indicated only by the absence of the interior mural painting. The upper end of this mural also indicates the former height of the aisles.[48] The interior has a Baroque character due to the large arched windows, but the basic Romanesque structure is still fully expressed.[57] The eastern part of the central nave and the side aisles in front of the eastern pillars are one step higher than the seating area of the nave and are therefore at the same level as the choir. There are the pulpit and the lectern.

Like the nave, the east choir, which is simply plastered in a light color, is separated from the central nave by a round arch that rests on wall supports at the corners of the choir. With a width of 5.50 meters and a length of 5.50 meters, it is almost square in plan, but slightly lower than the main body of the nave due to its elevated position by one step.[48] The back of the altar table, with the winged altar in the center of the choir arch, is illuminated by the large Baroque window in the east wall of the choir.

The western part of the church, with the basements of both towers, the eastern intermediate bays and the western extension of the central nave up to the second pair of piers, is separated from the main space of the church. To the north of the Gothic entrance hall, this separation consists of a wall that was added later. The area separated in the western part is used as a parish hall and winter church.[28] The area visually separated from the outside in the southern view, namely the towers and the adjoining intermediate bay with the portal zone and the Maurice chapel, is also recognizable in the interior layout.[48] The western extension of the central nave has a flat-beamed ceiling. The northern part, i.e. the extension of the northern aisle to the west, is connected to the chancel by two pointed arches running along the length of the church. The arches, the adjoining two-bay groined vault to the north and the corner of the north tower are supported by a square pillar one meter thick. The first floor of the north tower, with the adjoining intermediate bay, thus forms an optically separate part of the community room, in which a kitchenette is installed. Corresponding columns on the south side of the presbytery and the bricked arches between them indicate a similar construction method. However, while the eastern vault on the south side of the entrance hall has been preserved, the western vault in the south tower has been removed. In 1966, a staircase was installed there, with a toilet room below.[48] The other two supports of the belt arches are a pillar in the extension of the partition wall between the parish hall and the nave, which originally separated the side and main naves of the church, and the western outer wall.

The upper floor above the chancel is open to the interior of the church as a gallery. The organ is located in the central nave, the northern part of which is accessible from the central gallery through an arched doorway. South of the gallery, next to the tower, is the former Maurice Chapel with three lancet windows placed side by side. Up to the level of the window sill, the outer wall of the room is considerably thicker than above. The resulting wall ledge, 58 centimeters deep, is covered with sandstone slabs and still has a piscina on the right side. In the northeastern corner of the Maurice Chapel, a wall pillar, which runs vertically across the entire height of the room in the entrance hall and is decorated with mural paintings, breaks off irregularly above the floor. The interlocking with the walls indicates that it once supported the altar, the top of which was one meter above the floor.[48] The Maurice Chapel contains the weathered central columns of the vaulted sound openings of the towers, which had to be replaced with new ones. There are also two keystones from a ribbed vault, dated 1522 by their inscription.[33] The Maurice Chapel forms the passage to the gallery and contains a wooden staircase as an access to the south tower, the shaft of which is empty. In the north tower, a ladder leads to the belfry.[48]

Features[edit]

Murals[edit]

In several places in the interior of the church, there are large remnants of colored murals on the plaster. These paintings date back to the turn of the 14th and 15th centuries.[28] All the murals were restored during a renovation project in 1965-1967.[58]

Entrance hall[edit]

The murals in the vestibule at the southern main entrance to the monastery church were uncovered in 1909/1910.[58] The vault of the vestibule is decorated with floral ornaments in which four medallions, each with a half-figure, are embedded.[28] The figures may represent the four Fathers of the Church, but the attribution is not certain.[58] Mary under the cross and St. Christopher with the Christ Child on his shoulders are depicted on the walls of the entrance hall.[28] The text of a banner in the image of St. Christopher is difficult to read.[57] Another figure can be seen on the edge of the vault near the entrance to the south aisle. A three-line banner, also difficult to read, is painted on the pointed arch above this entrance.[58]

Main room[edit]

Other murals can be found in the south aisle of the church.[28] Some of the murals are only partially preserved.[58] They depict scenes from the legend of Christopher[28] according to the Legenda aurea, in particular his martyrdom in Lycia at the command of King Dagnus:[59] above the entrance on the west wall of the south aisle is a depiction of the pagan King Dagnus falling from his throne at the sight of Christopher, with the scourging of Christopher on the right. Below this are fragments of male figures on the left and male and female figures on the right. The white background of the paintings is decorated with red flowers, in the scourging scene with red stars. Above the upper left image, a two-line banner describes the scene, which is no longer fully legible.[58] The scenes on the south wall of the side aisle depict St. Christopher and the Christ Child on the riverbank at the top right, St. Christopher preaching at the top left, and St. Christopher praying at the bottom right. To the left of St. Christopher in the prayer scene are King Dagnus and another person; the explanatory banner can only be partially deciphered. At the bottom left, King Dagnus is depicted seated on his throne, with arrows floating in the air, which the king had shot at St. Christopher.[59] This scene also features a banner that is only partially legible. Once again, the backgrounds are decorated with red flowers and stars. There are fragments of further paintings on the left towards the eastern part of the south wall.[58] Some of the wall paintings were destroyed by subsequent alterations, particularly the installation of the large Baroque windows and the removal of the transept. The upper wall area of the side aisle walls is not painted; it was subsequently bricked up when the church was given a uniform gable roof and the basilical elevation was abandoned.

Gallery[edit]

The side walls of the gallery depict scenes relating to stories from the New Testament[28] and the Last Judgment. On the south side, the Resurrection[60] and the archangel Michael as the Weeper of Souls[58] are depicted, while on the north side, Jesus and the sleeping disciples in the Garden of Gethsemane[60] are shown, as well as the Hell's Dragon.[58] These murals were only uncovered during the restoration in 1963-1967.[60]

Altar[edit]

The winged altar, which has served as the main altar since the end of the 19th century, is composed of a central shrine with carved figures against a golden background and two hinged wings painted on both sides. Both the paintings on the wing panels and the lines of text on the front and back indicate that it was originally a Marian altar.[61] During a restoration in 1885-1887, it was redesigned as a crucifixion altarpiece.[62] The inscription on the altar wings indicates that the altar was consecrated in 1498. The altar was consecrated by Johannes, the titular bishop of Sidon and vicar general of Archbishop Berthold of Mainz.[63] There is no written record of the donor or donors of the altar.[64] The newly consecrated panel with carved and painted images of the Virgin Mary is mentioned in a certificate of indulgence from 1499.[61]

Prior to the restoration, the wings and the outer parts of the central shrine were incorporated separately from the central part into a Baroque altar wall, a practice that continued until the end of the 19th century.[28] This was also the case with the figures of the Judoc shrine.[41] The altar retable stands on a predella decorated with coats of arms and inscriptions above the sandstone ashlar altar table,[65] which is two steps higher than the choir.

A crucifixion group is the central element in the 1.86-meter-high by 1.78-meter-wide[64] central shrine. Originally, according to the dedication of the altar, there was certainly a representation of the Virgin Mary,[66] probably as a Madonna with a crown of rays or as a group crowning the Virgin Mary.[64] On either side of the central shrine are two figures of saints, one above the other: Mary Magdalene on the lower left, Catherine on the upper left, Barbara on the upper right, and Cyriacus on the lower right. These carved and painted figures are described in most publications as carvings from the workshop of Master Bartold Kastrop.[28][65][67][68] Other authors, however, reject the attribution to Kastrop's workshop,[69] or at least discuss it critically. The figures of the saints, the tracery and the pedestals are similar to those on the Marian retable in the church of St. Martin in Geismar, which can be attributed to Bartold Kastrop on the basis of an inscription.[64] On the other hand, the year in which the Reinhausen altarpiece was created - 1498 - argues against Kastrop as the master carver, since he was naturalized in Göttingen only a year later and until then had a workshop in Northeim, which was much further away. There are also differences in the facial expression and liveliness of the figures compared to Kastrop's Geismar carvings. Antje Middeldorf Kosegarten sees similarities to the figures on the carved altar in St. John's Church in Uslar and to a stone sacrament niche in St. John's Church in Göttingen.[62] Each carved figure is situated on a pedestal with beveled corners at the front, on which it is inscribed in black lettering: "S(an)c(t)a maria magdalena", "S(an)c(t)a katerina ora p(ro nobis)", "S(an)c(t)a barbara virgo" and "S(an)c(tu)s ciriacus mar(tyr)". The carved figures of Mary and John under the cross were newly created during the altar's restoration in 1885.[61] While some authors posit that the crucifixion group was also created at that time,[62] others suggest that the figure of the crucified Christ was crafted during the Baroque period,[68] while the cross itself was renewed at a later date.[61] Still others hypothesize that the entire crucifixion group is Baroque in origin.[64] The pedestals of the figures accompanying the cross are significantly taller than those of the older figures. They bridge a painted decorative strip at the lower edge of the altar centerpiece and raise the two figures to the level of the foot of the cross. These pedestals are not beveled and bear the inscriptions "Sca Maria" and "Scs Ioannes". The design of the letters is based on the older carved figures on the altar.[70]

The interior of the 88-centimetre-wide[64] panels each depicts a scene from the life of Mary.[28] The Annunciation is depicted at the top of the left-hand panel, while the visit to Elizabeth is shown on the right-hand panel. The birth of Jesus is depicted at the bottom of the left-hand panel, while the Adoration of the Magi is shown on the right-hand panel. A copperplate engraving by Martin Schongauer served as a model, at least for the last scene.[71] The authorship of the paintings is a matter of contention. According to more recent information, they originate from the same workshop as the backs of the wings, but cannot be attributed with certainty to the master himself.[67] In contrast, older art historians assume an unknown, less advanced painter with no other known works in Lower Saxony.[64] The backgrounds of the paintings are painted in gold, which identifies these pages as festive pages. Additionally, the horizontal strips on the upper and lower edges of the wings and the shrine, as well as in the middle of the wings, which serve to delimit the depictions, are also gold-colored.

The outer sides of the wings are the working side of the altar and have a red background. The Twelve Apostles are depicted in groups of three, with Matthias the Apostle in place of Judas Iscariot.[28] In addition to their attributes, they are labeled with their names on the top edge and the ledge separating the two rows. Eight figures also have their names on the hem of their robes.[61] The paintings are attributed to an unknown master, who is called the "Master of the Reinhausen Apostles" because of this work.[67][64] Other publications attribute the wing paintings to a student of Hans von Geismar or the Hildesheim Epiphanius Master,[62] or assume that the Master of the Reinhausen Apostles was a direct student of Hans von Geismar.[64] Some of these works were probably based on engravings by Martin Schongauer.[72] On the outside, the lower edge bears the inscription "Anno dni 1498 pletum est hec tabella / Jn honore gloriose marie virgini" as the date of production.[61] (In the year of our Lord 1498 this tablet was completed / In honor of the glorious Virgin Mary). The l in "[com]pletum" (completed) is missing the ascender; this word has also been interpreted as "pictum" (painted).[61]

The gilded horizontal moldings on the inside of the wings above and below the paintings, and the upper and lower horizontal moldings of the central shrine are embossed with lettering that originally formed a continuous set running across the wings and shrine. During the reconstruction of the central section, the lettering was replaced by a decorative band, so a larger portion is missing. At the top of the altar is the Salve Regina, an antiphon by Hermann von Reichenau:

„SALVE · REGINA · MATER · MISERICORDIE · VITA · DVLCED(o)

(et) SPES NOSTER (salve / ad te clamamus exsules filii Evae / ad te suspiramus ge)MENTES · ET FLENTES ·

IN · HAC · LACRIMARVM · VALLE · EYA · ERGO · ADVOC(ata nostra)“

(English: "Hail, Queen, Mother of Mercy, life, happiness and our hope, hail! To you we call, exiled children of Eve; to you we sigh, mourning and weeping in this valley of tears. Well then, our intercessor"), the lower, an antiphon set by Heinrich Isaac:

„AVE · SANCTISSI(m)A · MARIA · MATER · DEI · REGINA · CELI

PORTA · PARADISI (domina mundi / tu es singularis virgo pura / tu concepisti Jesum) SINE · PECCATO

TV · PEPERISTI · CREATOREM · ET · SALVATOREM · MVNDI · IN QVO (ego non dubito)“

(English: "Hail, most holy Mary, Mother of God, Queen of Heaven, Gateway to Paradise, Mistress of the world! You are a uniquely pure virgin, you conceived Jesus without sin, you gave birth to the Creator and Redeemer of the world, in whom I have no doubt"). In the center of the left wing is a verse from the Latin translation of the Song of Songs:

„TOTA · PVLCRA · ES · AMICA · MEA · ET · M(acula non est in te)“

(English: "You are perfectly beautiful, my friend, and there is no blemish on you"), on the right wing:

„O · FLORE(n)S · ROSA · MATER · DOMINI“

(English: "O blooming rose, mother of the Lord")

from an antiphon by Hermann von Reichenau.[61] Older literature also mentions deviant readings and other errors, especially for the script in places that are difficult to recognize.[73]

The predella was made later than the altarpieces. The date of origin ranges from the late 16th century[74] to the Baroque period[64] and the 19th century.[75][65][67] It bears two shields with upper coats of arms in intertwined rings in the center, which in some publications are interpreted as arms of alliance.[76][74] According to the current color scheme, the heraldic right coat of arms shows an upright red lion covered with golden balls in silver, on the red-silver beaded helmet four silver bars crossed at right angles, each with different tips at both ends, helmet covers red-silver. The heraldic left coat of arms shows in silver a red saddled and bridled, jumping black steed, on the silver beaded helmet a red saddled and bridled, jumping black steed in front of five black and silver plumes arranged in a fan shape, helmet covers black and silver. On older photos, showing the state before 1945, the relief of the coat of arms is recognizable without or with different painting.[77] Hans Georg Gmelin suggests that the arms belong to the von Werder and von Pentz families, but is not sure.[64] On both outer sides, next to the coats of arms, the text of the Words of Institution for Holy Communion is written in gold on a black background. These text panels are not yet present in photographs taken before 1945.[77]

Shrine of St. Judoc[edit]

On the east wall of the north aisle is the so-called St. Judoc shrine, the central part of a former winged altarpiece,[3] whose carved figures were integrated into a Baroque pulpit altar wall above the sounding board until the main altar was restored at the end of the 19th century.[41] After the dismantling of the pulpit altar wall and the reconstruction of the main altar, the shrine was placed on the east wall of the south aisle;[78] since the renovations of 1963-1967, it has been placed in the north aisle. The shrine is inscribed with the date 1507 and is considered to be the work of the Epiphanius Master from Hildesheim.[3]

Three figures - all holding a book - depict St. Judoc[79][67] as a pilgrim with a scallop shell on his head in the center, St. Bartholomew on the left, and Saint Blaise on the right. The central figure of Judoc is a good head taller than the flanking saints. They all stand on pedestals with inscriptions and have halos behind their heads on a gold background with the inscriptions: "SANCTVS.BARTHoLOMEVS.", "SANCTVS.JODOCVS." and "SACTVS.BLASIVS." (sic!). The pedestal inscriptions read "SANCTVS.BARTOLOMEVS" on the left and "SANCTVS.BLASIVS.EPISC" on the right,[80] although below the central figure is the year ".DVSENT.VNDE.VIF.HVNDERT.SEFVEN.". (1507).[81] The figure of Judoc also has inscriptions on the hem of his robe, interrupted by creases and folds in the hem of the robe: "CRISTVS" on the right arm holding the book, "MARIE" under that hand, "IHESVS" on the right collar (facing left from the viewer's perspective), "M" on the left collar, "SANCTVS" on the lower hem of the robe, "(...)OCVS" and "FA" after a folded section of the hem, and "MANG" at the bottom right.[82] All the inscriptions on the Judoc shrine are in early humanist capitals.[80] The inscriptions for the figures mentioned by Hector Wilhelm Heinrich Mithoff as "S.JACOB.MAJ" in the center, "SCS.BLASIVS" on the right, and "S.BARTHOLOMEVS" on the left no longer exist in this form;[41] Tobias Ulbrich thinks it possible that the inscription for James is on the invisible back of the base of the center figure.[65]

Since Mithoff's description, various authors have identified the eponymous figure in the center of the shrine as James the Great.[83][84][85] Ulbrich justifies this interpretation with the inscription mentioned by Mithoff, with the figure's pilgrim insignia including the scallop shell on the headdress, as well as with an alleged second pair of wings on the main altar, which prove a veneration of this saint in Reinhausen through figurative and pictorial representations of the legend of St. James.[65] In the nineteenth century, however, only a single wing was preserved as an additional altar wing alongside the two wings of the main altar, which was owned by Carl Oesterley at the time. It was assigned to a single altar by Mithoff together with the Gothic works of art installed in a pulpit altar wall at the time – the St. Judoc shrine, both wings of the main altar, four carved figures of saints from the shrine of the main altar.[41] This wing painting, which suffered significant deterioration in the 19th century[41] and has since undergone restoration,[86][87] is currently housed in the Landesmuseum Hannover.[66] It is no longer typically associated with the main altar, but rather with the St. Judoc shrine,[67][66] and is attributed to the painter Hans Raphon.[88] This altar wing was the outer left wing of the St. Judoc retable,[83] which, according to some published sources, originally comprised two pairs of wings.[66][83] Both the right wing and an inner pair of wings are missing.[83] However, the scenes depicted on the preserved wing are more clearly recognizable since the restoration, as there are two images arranged one above the other on each side. On the exterior, an image of the apostle James the Great is depicted at the top, accompanied by a staff, book, and the shell on the forehead of his hat. Below this is an image of St. Hubertus, who is shown with a crozier, book, mitre, and a hunting horn under his left hand. Both saints are depicted sitting on rocks, with St. James wearing a long beard. Two scenes from the legend of the St. Judoc are depicted on the inside: in the upper picture, St. Judoc's miracle at the spring, through which he saved Count Heymo, who was out hunting, from death; in the lower picture, the miraculous preservation of his corpse.[83][67] In the representation of the spring miracle, St. Judoc is depicted as a beardless young man in pilgrim's clothing, his cap lying on the ground and bearing the pilgrim's shell.[83] A single more recent description of the Reinhausen St. Judoc's retable recognizes only this one wing and describes not only the right wing but also the middle section as lost.[89]

Triumphal cross[edit]

The crucifix at the eastern end of the south aisle, which was later reworked, is also late Gothic and is said to have served as a triumphal cross.[3] It is 2.92 meters high[41] and was placed on the lower floor of the west transept in the 19th century.[41]

Stone sculptures[edit]

On the east wall of the choir there is a semicircular Romanesque stone relief. It depicts a cross on a hemisphere in an arch and below it a lion with a human head that appears to be devouring another human head.[28] The relief probably served as a tympanum in the vaulted area of the church's portal.[41]

In the eastern wall of the choir, there are also the remains of a Gothic stone sculpture with a central pinnacle that has a crown carried by two angels instead of a finial.[41] Its original function is interpreted as the crowning of a sacramental niche.[65][90] It is said to be a much cruder copy of a sacrament niche from St. John's Church in Göttingen.[62]

On the southern wall of the choir there is a stone sculpture of St. Christopher on a newer stone base, a relic of the worship of the church's patron saint, which dates back to the Romanesque period.[65] The saint is depicted with the Christ Child on his shoulders and a staff in his hand. Before the renovations in 1963-1967, the sculpture was located in a niche on the eastern wall of the southern aisle, below the shrine of St. Judoc.[91] It is one of the works of art in the church since the 19th century; before that it was located in the monastery courtyard.[92]

On the north wall of the choir is a detailed sculpture of Christ carrying his cross.[65] The well-preserved stone carving in the central area shows Christ rising from under the cross, a man in front of the cross holding Christ by a rope, and probably Simon of Cyrene standing behind Christ. Only the heads and parts of the upper bodies of three other persons in the background can be seen.

Gravestones[edit]

There is a cast iron tombstone on both the north and south walls of the choir. Both date from the second half of the 16th century.[3] The slab on the south wall of the choir was made for the monastery's pledge holder Christoph Wolff von Gudenberg, who died on February 15, 1569, and the one on the north wall was made for Melchior von Uslar and his wife Margarete von Ohle, who died on September 8, 1574.[66] On the east wall of the choir is a painted wooden plaque from 1735 commemorating Maria Magdalena Hinüber, born from Bush.[79] The two cast-iron memorial plaques were placed side by side on the south wall of the choir until after the Second World War; the wooden plaque hung together with another wooden epitaph above the plaques.[91] The second wooden plaque was also in the form of a medallion with side vines and a crown; it commemorated the bailiff Christian Erich Hinüber, who died in 1752 and is also named on the surviving plaque as the husband of the deceased.[93] Another stone gravestone from 1706 for Veit Andreas Hornhardt on the east wall of the north aisle is heavily weathered.[94] Hornhardt was Amtmann of the Reinhausen district from 1680 to 1705.[95]

-

Christoph Wolff from Gudenberg

-

Melchior from Uslar

-

M. Hinüber, born from Busch

-

V. A. Hornhardt

Baptismal font[edit]

The baptismal font is made of dark-stained wood. The base is four-sided, the basin with the baptismal font is supported by four neo-Romanesque columns and is octagonal. It bears the following inscription: "He who believes and is baptized shall be saved (Mark. 16:16)" On the eighth side there is a vine decoration.

Pulpit[edit]

The slightly raised pulpit to the left of the choir is a modern, very simple piece of furniture, as is the lectern to the right. The baroque pulpit, built into the former altar wall, was removed in 1885-1887.[28] Until the renovation in the 1960s, the pulpit stood on four neo-Romanesque columns on the front freestanding pillar.[96]

Vasa sacra[edit]

An inventory of the church treasury made after the introduction of the Reformation in 1542 listed seven chalices and paten, a pair of which belonged to the hospital, as well as a chalice kept outside. There was also a gilded monstrance.[97] Twenty years later, when the monastery was handed over to a Amtmann, another inventory was drawn up, in which there were hardly any sacred objects and only one chalice,[98] which was not described in detail.[43] Today, two silver communion chalices and two matching paten chalices have been preserved, but they are not on public display in the church.

The older goblet, made of gilded silver, has been dated to the 14th century. The 16.4-centimeter (5.9-inch) tall goblet has a flat, simple, round 14-centimeter (6-inch) diameter foot, a six-sided stem, a ribbed nodus, and a broadly flared, simple 11.7-centimeter (4-inch) diameter bowl. The low vertical rim of the foot is decorated with a row of dots and crosses, while the shaft has a surrounding ornament of crosses at the top and bottom. The inscription on the top of the foot reads "- CVRT - HANS - HENRICH - VON - VSLER - MARIA - VON - VSLER - ELSABET - SOPHIÆ - VON - VSLER - PIGATA - MAGDALENA - VON - VSLER - SCHONETTE - LISABETH - VON - VSLER". Based on the names mentioned, the inscription can most likely be dated to the second quarter of the 17th century, as the Brunswick-Lüneburg district commissioner and war commissary Curt Hans Heinrich von Uslar married Maria von Uslar in 1627 and had daughters Elisabeth Sophie, Beate Magdalena and Schonetta Elisabeth with her. The latter was already married in 1661, so the inscription was probably added well before that date. The inscription "FB / 1908" from a more recent period is carved under the foot of the chalice.[99]

The matching paten from the second quarter of the 17th century is also made of gilded silver and has a diameter of 15.8 centimeters. It bears an inscription on the rim, identical to that of the chalice except for two letters, and a disk cross.[100]

The second silver goblet is 18 centimeters high and dates from the end of the 16th century. The base and the foot, which is 14 centimeters in diameter, are in the shape of a hexagon, above which is a hexagonal stem with a flattened nodus on the side, bearing the letters "I H E S V S" in diamond form and, like the stem, decorated with engraved ornaments. The small, steeply rising bowl is ten centimeters in diameter. A reclining gilded crucifix is placed on one segment of the base, while the four-part Brunswick-Calenberg coat of arms of Duke Erich is engraved on the opposite segment. The inscription "TEMPLO REINHVSANO SACRVM" is engraved on the edge next to the crucifix, proving that it belonged to the Reinhausen church. The segment of the base bears the initials of the bailiff: "M(ATTHIAS) - S(CHILLING) - A(MT)M(ANN) - Z(V) - R(EIN)H(AVSEN)-", which allows an approximate dating: Matthias Schilling took office as ducal Amtmann of Reinhausen in 1578, Duke Erich died in 1584. Since both are named on the goblet, it must have been made during this period.[101]

The accompanying silver paten measures 15.1 centimeters in diameter. It bears the same engraved inscription as the chalice, "TEMPLO REINHVSANO SACRVM," on the bottom of the rim, and a disk cross on the top.[102]

Organ[edit]

The current organ in St. Christopher Church was built in 1967 by Rudolf Janke to replace an older organ. It has a five-stop manual division flanked by two freestanding pedal towers. The instrument has 16 stops on two manuals and pedal. The specification is as follows:[103][104]

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Couplers: II/I, I/P, II/P

The predecessor of the present organ was moved from Osterode am Harz to Reinhausen in 1841.[105] When the castle church of St. Jacobi in Osterode received a new organ from the master organ builder Johann Andreas Engelhardt,[106] the old organ was given free of charge to the St. Christopher Church in Reinhausen.[105]

Bells[edit]

For a long time there was only one large bell in the church, cast in bronze by the Radler bell foundry in Hildesheim in 1890.[105] In 1948, the company J.F. Weule from Bockenem made an hour bell weighing 60 kilograms and a quarter-hour bell weighing 45 kilograms for the church. These smaller bells are striking bells[105] and hang in the north tower of the church.

The oldest bell in the church was cast in 1585 by a bell founder named Rofmann,[107] who is not listed in the relevant directories, but was hung in the tower of St. Christopher's Church only after the Second World War. It originally came from East Prussia in the district of Mohrungen and was brought to Hamburg during the war to be melted down.[105] This bell is 60 centimeters high, 73.5 centimeters high with the crown, and has a diameter of 84.5 centimeters.[107] It weighs 360 kilograms[105] and bears the following inscription on its shoulder: "DVRCHS - FEVWR - BIN - ICH - GEFLOSSEN - MIT GOTTES - HILF HAT - MICH - ROFMAN - GEGOSSEN - 1585 -".[107]

Usage[edit]

The Counts of Reinhausen owned their ancestral castle on the rock above the village, now known as "Kirchberg", which they converted into a Stift at the end of the 11th century.[11] The former private church on this castle was thus given the function of a collegiate church.

When the canons' monastery was converted into a Benedictine monastery at the beginning of the 12th century, the church became a monastery church.[21] It was consecrated between 1107 and 1115 by Bishop Reinhard of Halberstadt.[22] In addition to being a monastery church, the church also served as a place of worship for the people of Reinhausen, with the monastery holding parish rights.[108]

With the introduction of the Reformation in 1542 by Duchess Elisabeth of Brunswick-Calenberg-Göttingen, the monastery under Abbot Johann Dutken had to convert to the Lutheran confession.[42] The abbot died in 1549.[109] From 1548 to 1553, the monastery and church were re-catholicized by Elizabeth's son Erich II as part of the Augsburg Interim,[110] and an abbot was appointed in the person of Peter of Utrecht.[44] At the end of the Interim in 1553, he refused to accept the new Lutheran doctrine and was arrested and expelled from Reinhausen. Jacob Pheffer was the last monk of the old monastery to die in Reinhausen in 1564.[111]

During the Reformation, the church was used by the parish of Reinhausen as a parish church[2] and the parish was merged with the parish of Diemarden.[108] The parish of Reinhausen was dissolved and the parish was looked after by the priest of Diemarden as a mother church without its own parish (mater coniuncta).[112] During the Thirty Years' War there was another attempt at re-Catholicization, but it lasted only from 1629 to 1631.[111] During this time the Lutheran pastor was expelled from the church. The inhabitants of Reinhausen were forced to accept Catholic holidays and services. It was also forbidden to attend the Protestant church service in the neighboring village of Diemarden under threat of punishment, and the way there was strictly controlled.[112]

The church building had been owned by the Dukes of Braunschweig-Lüneburg since the Reformation.[38] The first and second floors of the church were still being used in 1865 for the Reinhausen office, which was housed in the adjacent former cloister.[113] Interest crops were stored and sold from there. In 1956 the church was handed over to the parish in accordance with the provisions of the Loccum Treaty.[114]

The former monastery church now serves as the parish church of the Evangelical Lutheran Church and, together with the church in Diemarden, is served by a parish office that has been located in Reinhausen since 1962.[112] Both parishes belong to the church district of Göttingen-Münden[115] in the Hildesheim-Göttingen branch of the regional church of Hannover.[116] The Reinhausen congregation has nearly 900 members and maintains the church, the cemetery to the south and east, and the local kindergarten. [117] The church also serves as a branch of the Catholic parish of St. Michael in Göttingen. Until January 2010, Catholic Mass was celebrated in the monastery church twice a month, but since then, only on four holidays a year.[118][119]

The church also serves as a venue for church music and (sacred) concerts.[117] In 2015, the parish formed a concert team to plan and organize musical events.[120] The church is open daily from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. for viewing and prayer[121] and is marked as a "reliably open church".[122] It is located on the Via Scandinavica, one of the Camino de Santiago routes in Germany.[123]

In 2014, special services, concerts, lectures, guided tours and other events have been planned and held to celebrate the church's thousand years of history.[124] Since the exact date of the church's construction is not known and written records date back to a later period, the millennium celebration of the church refers to a time when the existence of the church can be considered certain based on the existing structural substance.[125]

Pastors[edit]

Since the introduction of the Reformation in 1542, the congregation has been served by Evangelical Lutheran pastors with brief interruptions. Many of the pastors who have served St. Christopher's since that time are known by name.[126]

List of pastors since the Reformation

- 16th cent: Wilhelm Krummel

- 1555–1566: Johannes Gödeken

- 1567: Georg Hetling

- 1576–1627: Valentin Hunolt

- 1627–1633: Heinrich Kahle (auch: Kalen)

- 1633–1666: Henning Sipken

- 1667–1668: Christoph Fischer

- 1668–1671: Johann Hase

- 1672–1687: Johann Hilmar Zindel

- 1688–1722: Johann Wilhelm Fein

- 1723–1742: Johann Daniel Schramm

- 1742–1752: Clemens Caspar Schaar

- 1753–1760: Johann Nicolaus Fuchs

- 1761: Johann Heinrich Froböse

- 1763–1772: Heinrich Adolf Reichmann

- 1772–1777: Johann Christoph Conrad Weipken

- 1777–1783: Heinrich Christoph Dissen

- 1784–1794: Georg August Borchers

- 1794–1805: Johann Christian Dille

- 1805–1807: Hermann Rudolf Jungblut

- 1807–1824: Heinrich August Ost

- 1826–1852: Johann Christian Heinrich Braukmann

- 1852–1888: Wilhelm Hermann Münchmeyer

- 1889–1916: Heinrich Ferdinand Heller

- 1916–1926: Heinrich Friedrich Wilhelm Stumpenhausen

- 1926–1936: Hermann Heinrich Friedrich Aulbert

- 1937: P. Schüler (?)

- 1937–1946: Theodor Bruno Georg Wilhelm Hoppe

- 1947–1972: Günther Heinze

- 1973–1993: Henning Behrmann

- 1994–2004: Götz Brakel

- 2004–2006 Pfarrstelle vakant

- 2006–2013: Uwe Raupach

- from February 2021: Julia Kettler[129]

References[edit]

- ^ Relief maps (Topografische Karte) 1:25.000 series

- ^ a b Müller, Ulfrid (1971). Klosterkirche Reinhausen. Large monuments. Munich Berlin: German Art Publisher. p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f Peter Ferdinand Lufen: Landkreis Göttingen, Teil 2. Altkreis Duderstadt mit den Gemeinden Friedland und Gleichen und den Samtgemeinden Gieboldehausen und Radolfshausen (= Christiane Segers-Glocke [Ed.]: Denkmaltopographie Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Baudenkmale in Niedersachsen. Volume 5.3). CW Niemeyer Book Publishers Ltd., Hameln 1997, ISBN 3-8271-8257-3, p. 280.

- ^ a b Ulfrid Müller: Die Klosterkirche in Reinhausen. In: Harald Seiler (Ed.): Niederdeutsche Beiträge zur Kunstgeschichte. Volume 9. German Art Publishers Ltd., Munich Berlin 1970, Kap. Der heutige bauliche Bestand der Klosterkirche, p. 13–14.

- ^ a b Online map on navigator.geolife.de, retrieved on August 22, 2017

- ^ Historical photos of the Kirchberg in Reinhausen, including photos before and after the fire at the official residence, on the website www.unser-reinhausen.de by Christian and Karin Schade, accessed on March 27, 2020

- ^ It is included in the exhibition of archaeological finds in the church and is labeled accordingly.

- ^ a b c Klaus Grote: Burgen. Untersuchungen und Befunde im südniedersächsischen Bergland. Section 5: Reinhausen, Gleichen parish, Göttingen district: Early to high medieval count's castle. In: www.grote-archaeologie.de. Klaus Grote, retrieved on December 30, 2018.

- ^ a b Entry by Stefan Eismann on Reinhausen in the scientific database "EBIDAT" of the European Castle Institute, retrieved on January 1, 2019.

- ^ Klaus Grote: Grabungen und größere Geländearbeiten der Kreisdenkmalpflege des Landkreises Göttingen im Jahre 1989. Chapter 2: Reinhausen: Kirchberg (early to high medieval castle wall). In: Göttingen Yearbook 38 (1990), p. 261-264. ISBN 3-88452-368-6

- ^ a b c Tobias Ulbrich: Zur Geschichte der Klosterkirche Reinhausen. Ed.: Evangelical Lutheran parish of Reinhausen, church council. Reinhausen 1993, Chapter 3.1.7 Die Gründungsgeschichte des Klosters Reinhausen – Die Gründung des Klosters – Die Genealogie der Grafen von Reinhausen, p. 50–54.

- ^ a b c d Ulfrid Müller: Klosterkirche Reinhausen (= Große Baudenkmäler. No. 257). German Art Publishers, Munich Berlin 1971, p. 3.

- ^ a b Peter Aufgebauer (Ed.): Burgenforschung in Südniedersachsen, Book publisher Göttinger Tageblatt, Göttingen 2001, ISBN 3-924781-42-7. Chapter 2: Wolfgang Petke: Stiftung und Reform von Reinhausen und die Burgenpolitik der Grafen von Winzenburg im hochmittelalterlichen Sachsen, p. 65–71.

- ^ Tour of the church on the website of the church building association Reinhausen, accessed February 2, 2019

- ^ a b Klaus Grote: Die mittelalterlichen Anlagen in Reinhausen. In: Führer zu archäologischen Denkmälern in Deutschland, Volume 17: Stadt und Landkreis Göttingen, Konrad Theiss Publisher, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3-8062-0544-2, p. 212–214

- ^ a b c d e f g Ulfrid Müller: Die Klosterkirche in Reinhausen. In: Harald Seiler (Ed.): Niederdeutsche Beiträge zur Kunstgeschichte. Volume 9. German Art Publishers Ltd., Munich Berlin 1970, Chapter Die Bauepochen der Klosterkirche, Section Bauperiode II, p. 35–38.

- ^ a b c d e f Ulfrid Müller: Die Klosterkirche in Reinhausen. In: Harald Seiler (Ed.): Niederdeutsche Beiträge zur Kunstgeschichte. Volume 9. German Kunstverlag GmbH, Munich Berlin 1970, chap. Die Bauepochen der Klosterkirche, Section Bauperiode I, p. 30–34.

- ^ a b c d e Tobias Ulbrich: Zur Geschichte der Klosterkirche Reinhausen. Ed.: Evangelical Lutheran parish of Reinhausen, church council. Reinhausen 1993, Chap. 1.1 Die Baugeschichte der ehemaligen Klosterkirche – Der ursprüngliche Kirchenbau (bis 1156), p. 2–8.

- ^ Klaus Grote: Churches and monasteries. Archaeological and architectural studies of medieval churches and monasteries in southern Lower Saxony. (Penultimate paragraph: Benedictine monastery and monastery church of St. Christopher). Retrieved December 20, 2013

- ^ Manfred Hamann: Urkundenbuch des Klosters Reinhausen. Göttingen-Grubenhagen document book, 3rd section. Hahnsche bookshop, Hanover 1991, ISBN 978-3-7752-5860-9, No. 11, S. 34–37.

- ^ a b c d Peter Aufgebauer (Ed.): Burgenforschung in Südniedersachsen, Book publisher Göttinger Tageblatt, Göttingen 2001, ISBN 3-924781-42-7. Chapter 2: Wolfgang Petke: Stiftung und Reform von Reinhausen und die Burgenpolitik der Grafen von Winzenburg im hochmittelalterlichen Sachsen, p. 71–74.

- ^ a b c Hildegard Krösche: Reinhausen – Kollegiatstift, dann Benediktiner (Vor 1086 bis 2. Hälfte 16. Jh.). Josef Dolle (Ed.): Niedersächsisches Klosterbuch. Verzeichnis der Klöster, Stifte, Kommenden und Beginenhäuser in Niedersachsen und Bremen von den Anfängen bis 1810, Teil 3: Marienthal bis Zeven (= Publications of the Institute for Regional Historical Research at the University of Göttingen, Volume 56,3). Publishing house for regional history, Bielefeld 2012, ISSN 0436-1229, ISBN 978-3-89534-959-1, p. 1291

- ^ Die Geschichte der Klosterkirche Lippoldsberg. 12. Der Bau der Klosterkirche. In: Klosterkirche Lippoldsberg. Retrieved on March 17, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Peter Ferdinand Lufen: Landkreis Göttingen, Teil 2. Altkreis Duderstadt mit den Gemeinden Friedland und Gleichen und den Samtgemeinden Gieboldehausen und Radolfshausen (= Christiane Segers-Glocke [Ed.]: Denkmaltopographie Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Baudenkmale in Niedersachsen. Volume 5.3). CW Niemeyer Book Publishers Ltd., Hameln 1997, ISBN 3-8271-8257-3, p. 277.

- ^ a b c d Peter Ferdinand Lufen: Landkreis Göttingen, Teil 2. Altkreis Duderstadt mit den Gemeinden Friedland und Gleichen und den Samtgemeinden Gieboldehausen und Radolfshausen (= Christiane Segers-Glocke [Ed.]: Denkmaltopographie Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Baudenkmale in Niedersachsen. Volume 5.3). CW Niemeyer Book Publishers Ltd., Hameln 1997, ISBN 3-8271-8257-3, p. 277.

- ^ a b c d e f Ulfrid Müller: Klosterkirche Reinhausen (= Große Baudenkmäler. No. 257). German Art Publishers, Munich Berlin 1971, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ulfrid Müller: Die Klosterkirche in Reinhausen. In: Harald Seiler (Ed.): Niederdeutsche Beiträge zur Kunstgeschichte. Volume 9. German Art Publishers Ltd., Munich Berlin 1970, Chap. Die Bauepochen der Klosterkirche, Section Bauperiode III A, p. 38–40.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Peter Ferdinand Lufen: Landkreis Göttingen, Teil 2. Altkreis Duderstadt mit den Gemeinden Friedland und Gleichen und den Samtgemeinden Gieboldehausen und Radolfshausen (= Christiane Segers-Glocke [Ed.]: Denkmaltopographie Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Baudenkmale in Niedersachsen. Volume 5.3). CW Niemeyer Book Publishers Ltd., Hameln 1997, ISBN 3-8271-8257-3, p. 279.

- ^ a b c d e Tobias Ulbrich: Zur Geschichte der Klosterkirche Reinhausen. Ed.: Evangelical Lutheran parish of Reinhausen, church council. Reinhausen 1993, Chap. 1.3 Die Baugeschichte der ehemaligen Klosterkirche – Die dritte Bauperiode (1290–1400), p. 12–16.

- ^ Ulfrid Müller: Die Klosterkirche in Reinhausen. In: Niederdeutsche Beiträge zur Kunstgeschichte, Volume 9, Ed.: Harald Seiler, German Art Publishers Munich Berlin 1970, p. 12, p. 38 and footnote 69, p. 44

- ^ Franciscus Lubecus: Göttinger Annalen von den Anfängen bis zum jahr 1588. Edited by Reinhard Vogelsang. Edited by: City of Göttingen (= Quellen zur Geschichte der Stadt Göttingen. Volume 1). Wallstein Publishing House, Göttingen 1994, ISBN 3-89244-088-3, pp. 99-100. Cf. also footnote 5, ibid. and Tobias Ulbrich: Zur Geschichte der Klosterkirche Reinhausen, p. 15–16 and footnote 45

- ^ a b c d e f g Ulfrid Müller: Die Klosterkirche in Reinhausen. In: Harald Seiler (Ed.): Niederdeutsche Beiträge zur Kunstgeschichte. Volume 9. German Art Publishers GmbH, Munich Berlin 1970, chap. Der heutige bauliche Bestand der Klosterkirche, Section Ostseite, p. 20–21.

- ^ a b c d Sabine Wehking: DI 66, No. 130 in: www.inschriften.net ("German inscriptions online"), urn:nbn:de:0238-di066g012k0013004, accessed on June 18, 2015

- ^ Ulfrid Müller: Die Klosterkirche in Reinhausen. In: Harald Seiler (Ed.): Niederdeutsche Beiträge zur Kunstgeschichte. Volume 9. German Art Publishers Ltd, Munich Berlin 1970, chap. Die Baugeschichte der Klosterkirche in ihren bisherigen Überlieferungen und Die Bauepochen der Klosterkirche and footnotes 15 and 17, pp. 11, 40 and 43.

- ^ According to recent research by Sabine Wehking: DI 66, no. 130 in: www.inschriften.net ("German inscriptions online"), urn:nbn:de:0238-di066g012k0013004, retrieved on June 18, 2015. According to Ulfrid Müller 1971 and Tobias Ulbrich 1993, it would read dominus matthias 1322 and frater remigius prior.

- ^ Thomas Küntzel: Gotische Maßwerkfliesen in Südniedersachsen. Ihr geschichtlicher Hintergrund und Überlegungen zur Produktion. In: Historical Society for Göttingen and the surrounding area (ed.): Göttinger Jahrbuch, Volume 43, Göttingen 1995, p. 19–40, here p. 28.

- ^ Hildegard Krösche: Reinhausen – Kollegiatstift, dann Benediktiner (Vor 1086 bis 2. Hälfte 16. Jh.). Josef Dolle (Ed.): Niedersächsisches Klosterbuch. Verzeichnis der Klöster, Stifte, Kommenden und Beginenhäuser in Niedersachsen und Bremen von den Anfängen bis 1810, Teil 3: Marienthal bis Zeven (= Publications of the Institute for Regional Historical Research at the University of Göttingen, Volume 56,3). Publishing house for regional history, Bielefeld 2012, ISSN 0436-1229, ISBN 978-3-89534-959-1, p. 1296

- ^ a b c d Ulfrid Müller: Die Klosterkirche in Reinhausen. In: Harald Seiler (Ed.): Niederdeutsche Beiträge zur Kunstgeschichte. Volume 9, German Art Publishers, Munich Berlin 1970, chap. Die Baugeschichte der Klosterkirche in ihren bisherigen Überlieferungen, S. 9–13.