Stern Hunting Lodge

The Stern Hunting Lodge in Potsdam was built between 1730 and 1732 under the reign of the Soldier King Frederick William I in the style of a simple Dutch town house. The contract for the construction was probably awarded to Cornelius van den Bosch, a grenadier and master carpenter from Holland, and the building was supervised by Pierre de Gayette, Captain of the Corps of Engineers and Court Architect.

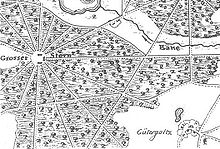

At the time of its construction, the building, which was only designed for hunting trips, stood at the center of an extensive area that had been developed for par force hunts since 1726 with the construction of a star-shaped system of tracks. The area converted for this hunt was given the name Parforceheide. Today, it stands between the 115 highway to the east and a new district built into the Parforceheide from 1970 to 1980 to the west, on the edge of the Potsdam district of Stern. Following the destruction of the city palace, the Stern hunting lodge is now the oldest surviving palace building in Potsdam. It is managed and maintained by the Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin-Brandenburg with the voluntary support of the Stern-Parforceheide Hunting Lodge Association.

History[edit]

The emergence of hunting lodges in the Mark Brandenburg[edit]

In the 16th century, Elector Joachim II Hector began building the first hunting lodges in Grimnitz, Bötzow (now Oranienburg), Grunewald and Köpenick around his residences in Berlin and Cölln in the Margraviate of Brandenburg. During the reign of the Great Elector Frederick William, further hunting lodges were built in the densely wooded and game-rich area around Berlin and Potsdam, including Groß Schönebeck and Glienicke.

Like his predecessors, the Soldier King Frederick William I was also a passionate hunter who pursued this passion in Königs Wusterhausen, located south-east of Berlin. The manor and castle of Wusterhausen, which he received as a gift from his father Elector Frederick III (King Frederick I of Prussia from 1701) at the age of ten in 1698, was converted into a hunting lodge after his accession to the throne.[1]

After his accession to the throne in February 1713, he made Potsdam his residence. Between 1725 and 1729, he had a "peasant heath" south-east of the city gates opened up for his extensive hunts - the so-called par force heath. The extensive, flat terrain with sparse woodland and little undergrowth was ideal for these hunts on horseback, which had become a popular form of hunting at German courts at the end of the 17th century. In addition to fast dogs and horses, this type of hunting required clear terrain in order to be able to pursue the game over long distances until it collapsed exhausted. To make it easier for the widely dispersed hunting party to find their way around, the area was divided into segments by sixteen star-shaped aisles (racks). From the respective sections of the approximately one hundred square kilometer hunting ground, the hunters found their way back to their meeting point via the straight aisles that led to the center of the star.

Construction of a building ensemble and use[edit]

Slightly offset from the center of the star, between two rays, the Soldier King had a hunting lodge built between 1730 and 1732 in the style of a simple Dutch town house, which he named after the location. From the following year onwards, he had the Dutch Quarter in Potsdam built from a large number of similar houses. In addition to the extension to his hunting lodge in Königs Wusterhausen, the small hunting lodge Stern was the only new building that the soldier king, who was very frugal, had built for himself. The half-timbered house a few meters to the southwest was probably built at the same time as the hunting lodge and housed the castellan, who was also granted bar rights. The castellan's house was used for catering until 1992. The farm buildings included a stable building in the north-east, completed in 1733, in which at least 18 horses could be stabled. It has been used for residential purposes since a conversion around 1930.[2] A barn with a small stable, a wash house with a privy and a well in the center of the star are no longer preserved. The structural remains of a brick oven were uncovered between 2006 and 2009 and rebuilt in 2011/2012 in accordance with the preservation order.[3]

When Frederick the Great came to power in 1740, par force hunts no longer took place around Potsdam. In his treatise "Antimachiavell", in which Frederick wrote down his thoughts on the tasks and aims of the exercise of princely power, he rejected hunting as a princely pastime and described hunting as one of those sensual pleasures that are hard on the body but do nothing for the spirit.[4] His successors, Frederick William II and Frederick William III, had no interest either. In 1791, there were only a few driven hunts at Stern and during the Napoleonic occupation of Prussia, the hunting lodge served as accommodation for French soldiers. It was only under Frederick William IV, who in 1847 had the Hubertusstock hunting lodge built on the edge of the Schorfheide north of Berlin, the last Hohenzollern hunting lodge in the Mark Brandenburg, that hunting events took place again. As early as 1828, Prince Carl, a younger brother of the king, revived par force hunting, which was practiced until the 1890s.

Changes of use after the end of the monarchy[edit]

After the First World War and the end of the monarchy, the building was temporarily rented out to artists. Like most Hohenzollern palaces, the Stern hunting lodge came into the care of the Prussian "Administration of State Palaces and Gardens", founded on April 1 of the same year and since 1995 the "Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin-Brandenburg", in 1927. After the Second World War, it served as accommodation for the military protection unit for the British delegation during the Potsdam Conference and the entire complex was used as a vacation camp for schoolchildren from 1949 until the 1970s. After extensive renovation work in the 1980s, the hunting lodge was furnished with items from Königs Wusterhausen Castle for museum use, but these are no longer part of the collection today. Due to excessive pollution from wood preservatives, the building was closed for years from 1996 and could only be visited by appointment. Following the subsequent renovation work, it has been open to the public again since 2007.

The Parforceheide lost its area over time. Today, only eight paths of the sixteen-path snow system remain. In the north, the construction of the first Prussian Berlin-Potsdam railroad line and the Teltow Canal led to major losses of territory. In the west, the construction of the Wetzlarer Bahn and the AVUS with its later extension to the Autobahn 115, which passes close to the hunting lodge, and in the south, the Nuthe expressway. In addition, the residential areas of Stern, Drewitz and Kirchsteigfeld in Potsdam were built on former woodland.[5]

Hunting lodge Stern[edit]

Aversion to the splendor of the Baroque[edit]

In terms of cultural history, the 17th and 18th centuries are regarded as the most magnificent period in the history of hunting at European courts. In courtly society, it was a pleasure and pastime, but also a symbol of status and self-expression. It also served to cultivate dynastic and diplomatic relations and, with the spread of absolutism, became a matter of prestige for the pomp-loving sovereigns. Even for the lower nobility, the right to hunt - in a society divided into classes - was a visible enhancement that enabled them to distinguish themselves more clearly from the wealthy, non-noble classes. In addition to hunting events, glittering celebrations often took place, so that hunting lodges were built especially for the accommodation of guests, beginning as early as the 16th century, or existing, conveniently located buildings were furnished solely for this purpose.

Frederick William I had a strong aversion to the luxurious lifestyle of the princely houses. He also rejected the exuberant decorative forms of Baroque architecture and preferred the clarity, clarity and cleanliness of the façades. Under his rule, the architectural style of Brandenburg-Prussia was dominated by practicality. The simplicity of the Stern hunting lodge reflects the frugal and spartan lifestyle of the soldier king. Particularly when compared with Moritzburg Castle near Dresden, which was converted into a Baroque hunting lodge at the same time, from 1723 to 1733, by the Elector of Saxony and King of Poland Frederick Augustus I/II, it becomes clear that the Prussian monarch did not use architecture for representation, as was generally the case at European courts.[6]

Choice of Dutch architecture[edit]

In the Mark, there had already been a strong connection to Holland since the beginning of the expansion of the country by Albrecht the Bear in the 12th century, which flourished again in the 17th and 18th centuries. The marriage of the Great Elector Frederick William to Luise Henriette of Orange-Nassau in 1646 encouraged the settlement of Dutch or Dutch-trained specialists for agriculture, landscaping, canal and dyke construction. In his Wanderungen durch die Mark Brandenburg, Theodor Fontane notes: "Colonists were moved into the country, houses were built, outbuildings were laid out and all the details associated with agriculture were immediately carried out with diligence" and the Dutch were "[...] the real agricultural instructors for the Mark, especially for the Havelland".[7] Frederick William I also vigorously pursued the economic development of the country that had already been pursued under his grandfather, the Great Elector, with the settlement of foreign craftsmen and the simultaneous establishment of a strong army. Both resulted from the consequences and experiences of the Thirty Years' War, from which the Margraviate of Brandenburg had suffered particularly badly.

After the first expansion of the Potsdam residence into a garrison town under the Soldier King, the so-called "first baroque expansion of the town" from 1722 to 1725, the "second baroque expansion of the town" took place between 1732 and 1742 due to the increase in civilian and military personnel. This period, between 1734 and 1742, also saw the construction of a Dutch Quarter. These houses were built for craftsmen whom the Soldier King had recruited for the expansion of Potsdam on his last trip to Holland in 1732. Through his family ties to the Dutch royal house and his study trips in 1700, 1704 and 1732, Frederick William I became acquainted with the engineering skills of the Dutch, who knew how to drain swampy terrain. The same soil conditions, which were difficult for building on, also existed in Potsdam. He was also impressed by the inexpensive, quick construction of Dutch brick houses.[8]

Architecture[edit]

Overview[edit]

The 17th century brick houses in Amsterdam's Noortse Bosch weaving district and the simple bell gables of Zaandam, as well as the simpler town houses in Leiden and Haarlem, probably served as models for the Dutch houses in Potsdam.[9][10] As the Stern hunting lodge with the same architecture was completed shortly before construction of the first houses in the Dutch Quarter began, it is reasonable to assume that it served as a model house for the always economically minded Soldier King in order to better estimate the construction time and costs for the larger project. The name of the architect is not certain; it is possible that the house was built according to a plan obtained directly from Holland.[11] The contract for the construction was probably awarded to the grenadier and master carpenter Cornelius van den Bosch (1679–1741) from Schipluiden near Delft,[12] other sources mention Schipley near Grafenhaag (The Hague),[13] who came to Potsdam around 1720. The first mention of the Dutchman can be found in a rank roll (list of names) dated 1726 as a "long fellow" in the Royal Regiment of Foot.[14] Like the soldiers of the time, he also pursued a civilian profession after his daily military service and is mentioned in the construction files for the hunting lodge in connection with the ordering of timber. The French-born captain of the Corps of Engineers and court architect Pierre de Gayette supervised the construction, as evidenced by his signature under brick deliveries "for the new house in the royal par force garden" in August/September 1730.[10]

Exterior design[edit]

The Stern hunting lodge, modeled on the style of simple Dutch town houses, is a single-storey building with a bell gable and gabled roof. The outer walls, which rest on a rectangular ground plan, are made of red, unplastered brickwork. On the orders of Frederick William I, bricks with a uniform size of around 27 × 13 × 8 centimetres were used.[9] The square quarter bricks at the corners of the gables and the brickwork in a special plait shape on the courtyard façade are reminiscent of Dutch brickwork. The five high sash windows in the three-axis front façade, the entrance door and two sash windows in each of the side walls are designed with glazing bars and plain frames, as had become fashionable in the better houses from 1690, first in England and then in Holland.

The three windows in the upper section, whose upper edge forms a line to the attic, simulate a two-storey structure. The smaller sliding windows with shutters, two on each side wall and five at the rear, illuminate the adjoining rooms. A wooden door in the south-west wall and at the rear of the house are side entrances that lead into the hallway and the adjutant's room. The only architectural decoration is a blind window with a star ornament in the bell gable and a relief above the central French window showing the head of the Roman goddess Diana with hunting equipment. The decorative elements made of light-colored sandstone were added later in the 19th century.[15]

Interior design[edit]

Like the simple exterior architecture, the design of the interior building is deliberately purist in the spirit of Frederick William I, in keeping with the simple, bourgeois living culture of the Dutch, which corresponded to his idea of clarity and cleanliness. The modest room program includes a hall adjoined by a corridor and the kitchen, followed by an adjutant's room and a bedroom.

The hall takes up the entire width of the front façade and almost half of the house. It is the largest room in the building and was used for socializing after the hunt. The dome-shaped ceiling, divided into panels, extends into the attic area. The walls are clad with yellowish-brown wood paneling and the floor is covered with floorboards. The room was heated by an open fireplace made of dark red marble on the east wall, opposite the entrance door. The few room decorations include a mirror framed with golden ornamentation and five paintings set into the wall showing Frederick William I in various hunting scenes. The paintings were probably created by the painter Georg Lisiewski. Hunting trophies hang from the window pillars, indicating the use of the building. The five gilded stag heads carved out of wood with real antlers are the antlers of Frederick William I's favorite stag, known as the Great Hans, from the years 1732 to 1736. Little is known of the original furnishings, which are no longer preserved. An inventory list from 1826 lists a few items that may have been part of the hall's first furnishings: "A long pine table painted with oil paint; four small green-painted square tables; three similar triangular corner tables; an old, completely unusable bench."[16]

Next to the fireplace, a door leads into the corridor that connects the hall with the rooms in the rear half of the house. The walls are whitewashed and the floor, as in the kitchen and the adjutant's room, is covered with reddish-brown, marble-like limestone slabs, which were also known as cutting stones or Gothland stones in the 18th century and were often used as ships' ballast. The manganese-coloured tiles of the skirting board in the rooms are ornamentally decorated with cornflowers and chequerboard flowers as well as stylized foliage and come from the Rotterdam manufactory of the former guild of tile burners. In addition to the entrances to the kitchen and the adjutant's room, another door in the south-west wall leads out of the building.

The kitchen on the north-east side was mainly used for warming and serving food, which was probably prepared in the castellan's house. The walls are tiled in white from floor to ceiling, as is the chimney above the brick-built stove. The original furnishings include a low built-in cupboard with a marble top under the windows, on which food could be served, and a marble sink next to it with a drain. The water pump with brass bladder is no longer preserved. The inventory list from 1826 lists further items for the kitchen: "A blue-painted Schab [crockery cupboard]; [...] six bowls, three candlesticks, two faience salt cellars, dating from the Elector's time, all damaged; a jug; two jugs of Chinese porcelain with silver and gilded lids; a damaged glass goblet with gilding".[17]

The adjutant was accommodated in the room on the south-east side of the house. It was also the anteroom and the only way to get into the adjoining bedroom of the king. The building could also be entered and exited from here through a door. The whitewashed bedroom is dominated by a green-painted fitted wall with white framed panels. An alcove is set into the middle. Behind the concealed doors on either side of the bed recess, a staircase leads to the attic on the right and to the cellar on the left. The room was heated by a simple red-brick fireplace. As in the hall, the floor is covered with floorboards.

Literature[edit]

- Literature by and about Stern Hunting Lodge in the German National Library catalogue

- Theo M. Elsing: Das Holländische Viertel in Potsdam. Potsdam o. J.

- Jan Feustel: Jagdschloß Stern in Potsdam. In: Die Mark Brandenburg. Auf Pirsch in der Mark. Jagd und Jagdschlösser. Heft 58, Marika Großer, Berlin 2005, ISBN 978-3-910134-27-0, pp. 14–21

- Theodor Fontane: Wanderungen durch die Mark Brandenburg. Teil III, Havelland. 1. Auflage 1873, Nymphenburger, München-Frankfurt/M.-Berlin 1971, ISBN 3-485-00293-3

- Julius Haeckel: Neues vom Jagdschloss Stern. Mitteilungen des Vereins für die Geschichte Potsdams, Band V, Heft 7, Potsdam 1912, S. 1–9

- Peter Hutter: Die Jagdschlösser der Hohenzollern in der Mark Brandenburg. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten Berlin (Hrsg.): 450 Jahre Jagdschloß Grunewald 1542–1992, Teil I. (Aufsätze). Berlin 1992, pp. 125–141

- Hans Pappenheim: Jagdgärten mit Sternschneisen im 18. Jahrhundert. Brandenburgische Jahrbücher, Nr. 14/15 (Die alten Gärten und ländlichen Parke in der Mark Brandenburg), Potsdam/Berlin 1939, pp. 20–32

- Adelheid Schendel: Jagdschloss Stern, Parforceheide. Edition Hentrich, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-89468-277-9

External links[edit]

- Entry for the monument object number 09156058 in the monument database of the state of Brandenburg

- Friends of Jagdschloss Stern-Parforceheide e.V.

- Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin-Brandenburg

References[edit]

- ^ "Joachim II Hektor | Hohenzollern Dynasty, Prussia, Reformer | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2024-03-15. Retrieved 2024-04-24.

- ^ Schendel: Jagdschloss Stern, Parforceheide, p. 25.

- ^ Förderverein Jagdschloss Stern – Parforceheide e. V.: Backofen. Retrieved March 18, 2024.

- ^ Gustav Berthold Volz (Hrsg.): Die Werke Friedrichs des Großen. Band 7: Antimachiavell und Testamente, 14. Kapitel, Published by Reimar Hobbing, Berlin 1913.

- ^ "Das Schloss – Jagdschloss Stern". jagdschloss-stern.de. Retrieved 2024-04-24.

- ^ "The Prussian Baroque (1701-1740)". www.lempertz.com. Retrieved 2024-04-24.

- ^ Fontane: Wanderungen durch die Mark Brandenburg. Teil III, S. 134, p. 420.

- ^ Fischer, Reinhard E. "Potsdam: Die Stadtgeschichte." Verlag Friedrich Pustet, 2010.

- ^ a b Elsing: Das Holländische Viertel in Potsdam, p. 34.

- ^ a b Schendel: Jagdschloss Stern, Parforceheide, p. 12.

- ^ Gerd Bartoschek: Jagdschloß Stern. In: Potsdam-Sanssouci Palaces and Gardens Foundation (ed.): Potsdamer Schlösser und Gärten. Bau- und Gartenkunst von 17. bis 20. Jahrhundert, p. 64.

- ^ Elsing: Das Holländische Viertel in Potsdam, p. 33.

- ^ Schendel: Jagdschloss Stern, Parforceheide, p. 11.

- ^ SPSG: Die Historische Mühle, p. 6.

- ^ Elsing: Das Holländische Viertel in Potsdam, p. 30.

- ^ Schendel: Jagdschloss Stern, Parforceheide, p. 15.

- ^ Schendel: Jagdschloss Stern, Parforceheide, p. 16.