Syriac Gospels, British Library, Add. 7170

British Library, Add. 7170 is a Syriac manuscript dated to circa 1220 CE. This is one of the few highly illustrated Middle-Eastern Christian manuscripts from the 13th century. The colophon is lost, but a scribal note indicates that the manuscript was created at the time of Patriarch John and Maphrian Ignatius, who may be identified as John XII of Antioch (1208-1220) and Ignatius III David (1215-1222 as maphrian), respectively, which gives a completion date circa 1215–1220.[4] The location where the manuscript was created is uncertain, but is generally thought to be the Jazira region near Mosul, possibly at the monastery of Deir Mar Mattai, due to artistic similarities with another manuscript securely attributed to Mosul (Vatican Library, Ms. Syr. 559).[5]

The manuscript is written in the Syriac language, in Estrangela script.[1] It is considered as a near twin of the Syriac Gospels, Vatican Library, Syr. 559 manuscript, which is securely attributed to the Deir Mar Mattai in northern Iraq (Jazira region).[1] It was probably produced at Mar Mattai itself, or in a related monastery, possibly in the Mardin Monastery, seat of the Syrian Jacobin patriarcate since 1207.[1]

The manuscript is derived from the Byzantine tradition, but stylistically has a lot in common with Islamic illustrated manuscripts such as the Maqamat al-Hariri, pointing to a common pictorial tradition that existed since circa 1180 CE in Syria and Iraq.[1] Some of the illustrations of these manuscript have been characterized as "illustration byzantine traitée à la manière arabe" ("Byzantine illustration treated in the Arab style").[1]

-

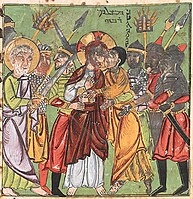

Betrayal of Jesus by Judas.

-

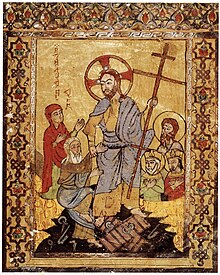

Miniature

-

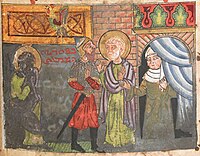

Miniature

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f The Glory of Byzantium: Art and Culture of the Middle Byzantine Era, A.D. 843-1261. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1997. pp. 384–385. ISBN 978-0-87099-777-8.

- ^ British Library notice

- ^ "Syriac Lectionary". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ Snelders 2010, p. 1.

- ^ Snelders 2010, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Stewart, Angus (2019). 18 Hülegü: the New Constantine? in "Syria in Crusader Times". Edinburgh University Press. pp. 326–327. doi:10.1515/9781474429726-022.

p.326: image (...) p.327: When the work was completed Hülegü was at most three years old, and possibly not yet even conceived. (...) p.328 The identification of these figures as being specifically 'Mongol' is in itself questionable. Their costume, for example, is only 'Oriental' in the sense of being Near Eastern – the Byzantine loros-costume, but with robes decorated with tiraz bands common to the Islamic world, and with 'Seljuq' style crowns. Similarly, when analysed artistically, the images fit into a distinctly Near Eastern mould, having much in common with contemporary work from northern Syria and Mesopotamia produced in an Islamic milieu.

Sources[edit]

- Snelders, B. (2010). Identity and Christian-Muslim interaction : medieval art of the Syrian Orthodox from the Mosul area. Peeters, Leuven.

- The Glory of Byzantium: Art and Culture of the Middle Byzantine Era, A.D. 843-1261. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1997. pp. 384–385. ISBN 978-0-87099-777-8. (PdF)

![Constantine and Helen, with Seljuq-style crowns and Near-Eastern clothing with tiraz bands.[6]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/56/Hulagu_and_Doquz-Qatun_in_Syriac_Bible.jpg/165px-Hulagu_and_Doquz-Qatun_in_Syriac_Bible.jpg)