Talk:Clef/Archive 1

| This is an archive of past discussions. Do not edit the contents of this page. If you wish to start a new discussion or revive an old one, please do so on the current talk page. |

| Archive 1 |

Multiple clefs

This paragraph is inaccurate:

- But why all these different clefs? Although only four are common today, as many as eight have been used previously. The reason is, oddly not a musical but a mechanical one. In the days of early music printing presses (i.e, during the Renaissance), ledger lines were difficult to print, so a wide variety of clefs were subsequently used.

In fact, the use of moveable clefs long precedes printed music; it goes back to Gregorian chant. However, avoidance of ledger lines was certainly a prime motivation. I'll try and find some examples of Gregorian chant clefs. --Wahoofive 05:14, 14 Mar 2005 (UTC)

Huge graphics

Why are the graphics so huge? --Wahoofive 05:19, 14 Mar 2005 (UTC)

Minor reorg

I'd like to propose a minor reorg:

- Move the section called "Notes" to the bottom, and give it a more descriptive name

- Create a new section header after the first paragraph (perhaps "Use of clefs") to bring the TOC higher up Wikipedia:Guide_to_Layout.

- Add a section at the bottom for historical information.

Actually, most of the "notes" strike me as kind of meaningless, but if we want to keep this information, it could be presented more effectively. I'll work on it.

--Wahoofive 05:27, 14 Mar 2005 (UTC)

I agree. I will try to integrate the notes into the main article - they don't read easily out of contxt at the bottom! - Dan 18:51, 12 October 2005 (UTC)

- I'm happy you started on this. Be aware that the original text at the bottom was some kind of sight-transposition system used extensively in Europe. For example, consider this sentence: The G clef on the bottom line is called "French Violin clef" which works for Eb clarinet or Eb trumpet music. This doesn't make much sense where you've put it in the middle of the treble-clef section. To be sure, the previous version stank, but we should remove the tranposition references from the interior of the topic, and find a way to summarize the transposition system -- perhaps in a separate article or as part of sight reading. I'm not knowledgeable enough about the system to write about it, although the principles are pretty obvious. —Wahoofive (talk) 20:16, 12 October 2005 (UTC)

- I agree the bullet points don't make much sense where they are, but I think they could with a little work. I put them in what I thought was logically the most relvant section, so the French clef bit is in with the G clef (not treble clef) - I just didn't think it warranted it's own subsection. Then again, maybe it does? - Dan 21:58, 13 October 2005 (UTC)

Treble

The following was recently added:

- The origin of the application of the term treble, a doublet of "triple" or "threefold" (from Latin triplus, "triple"; cf. "double" from duplus), to the highest voice or part comes from early plainsong. The chief melody was given to the tenor, the second part to the alto (discantus, or contralto), and where a third part (triplum) was added, it was assigned to the highest voice, the soprano or treble.

Does anyone have sources for this? This is not what I learned in music history class: the two voices added to the tenor were the 'contratenor altus" and the "contratenor bassus". Soprano parts are relatively rare in Medieval music. This etymology sounds superficially convincing but.... —Wahoofive (talk) 22:10, 20 January 2006 (UTC)

- The OED Online says “The musical use [of ‘treble’] is supposed to have arisen from ... [etymology exactly as quoted above] ... but the history is somewhat obscure, esp. as triplex, triplus meant ‘threefold’ and not ‘third’, and in OF. treble was applied to a trio.” —Blotwell 04:18, 27 January 2006 (UTC)

Wahoofive is referring to the late mediaeval period of 'Ars Nova', say 1350 onward, whereas the use of 'duplum' and 'triplum' for parts added to a 'tenor' relates to Aquitaine and Notre Dame organum in around 1200-1300. The reference to 'plainsong' in the text should read 'organum'. The words were preserved by their use for the parts of motets. Reference [1] 84.67.16.111 (talk) 23:43, 2 December 2008 (UTC)

Treble

i wouldnt say the treble was most commonly used. yes, probably, which is what i changed on the main pg. . . . . ---leila

- But the treble clef is used: a). in short-score choral music equally with bass clef (1:1); b). in open-score choral music for SAT (not B), ie (3:1) (running total 4:2); c). piano music (let's say 1:1) (RT = 5:3); d). in 3-stave organ music, bass clef claws one back (1:2) (RT = 6:4); e). string quartet (2:1 - let's ignore va clef) (RT = 8:5); f). turning to the orchestra now: WW Fl (picc), Ob (Cor Ang), Cl (& Bass Cl) all use treble clef, whilst Bn (DBn) only uses bass clef (so min. 3:1, arguably 6:2, though could be more in terms of parts actually sitting on players' desks) (RT = 11:6); g). brass: Hn & Tpt use treble clef, Tenor Trb uses tenor clef (let's ignore), Bs Trb & Tb use bass clef - let's say 3:2 (though should be 4Hn & 3Tpt = 7, vs. 1Trb & 1Tb = 2) (RT = 14:8); h). harp 1:1 (RT = 15:9); i). timpani, bass clef (RT = 15:10). Furthermore, in UK brass band music almost all instruments (Cornet, Flugel, Tenor horn, Euphonium, Baritone, Ten Trb, & Tb) are written in treble clef; only the bass trb is in the bass clef - 7:1 (min) (RT = 22:11). Even in pieces scored for unusual combinations (eg Villa-Lobos's popular Bachianas Brasileiras No.5 for 8 cellos & soprano) the treble clef is frequently used in the cello parts). In what way is the treble clef only "probably" the most commonly used?? I've therefore taken the liberty of changing it back; please forgive me. 195.217.52.130 18:54, 4 August 2006 (UTC)

C clef

I've done a fair amount of singing in church choirs. One use of the C clef that I've seen that is not listed in the article: sometimes tenor parts have a C clef that is positioned so that middle C is the space between the 3rd and 4th lines. It's equivalent to a treble clef with an 8 under it, which I see much more often. I don't see the C clef used in this way nearly as often, but I do see it occasionally. 66.126.103.122 02:16, 7 November 2006 (UTC)

Alto Clef

In several places, the article portrays the alto clef as exclusively used by the viola, but it is also found in parts published for the tenor and alto trombones, albeit not as commonly as the tenor clef. Serious trombonists need to know this clef. --Sommerfeld 19:53, 18 December 2006 (UTC)

- I've made some changes to this effect (hopefully improvements...) --Sommerfeld 22:47, 19 December 2006 (UTC)

This article in general has a big problem distinguishing modern clef usage and obsolete clef usage. Just because music currently exists with a particular clef usage doesn't make that usage modern. In the nineteenth century, for example, it was common to write treble clef cello parts an octave above concert pitch (in order to obviate the need for the tenor clef). No one has done that for a very long time, but orchestral scores using that notation persist, although in my experience their corresponding cello extraction parts always use the tenor clef (to the great confusion of a certain orchestral conductor of my acquaintance). Anyway, the alto clef in modern notation is used exclusively by the viola. The alto clef trombone parts one encounters from time to time are merely reproductions of old scores or parts. No one writes trombone parts any more in the alto clef. 66.188.140.155 08:02, 6 January 2007 (UTC)

Alto/Tenor Clef

The two pictures, the alto clef and the tenor clef are the same image.Scottydude 22:46, 25 December 2006 (UTC)

Mnemonics

Are these really necessary? The article is not meant to be a teaching aid but a... encyclopedia article! Not to mention they take up a good bit of space. I think listing the notes found on the staff would be sufficient. -- ßottesiηi (talk) 21:01, 3 January 2007 (UTC)

They're not at all necessary, and I've taken the liberty of deleting them. 66.188.140.155 08:08, 6 January 2007 (UTC)

Clarity

Someone has restored some old wordings which lack clarity. Some better wording should be reached that defines the function of the clef clearly and succinctly. In particular, I think that this wording should incorporate the fact that:

1. A clef does not assign names to the lines and spaces of the staff, but assigns A name to ONE line. (The other lines and spaces following from this of course.) This is important because it prepares the way for:

2. Each clef assigns some particular note: the presentation of which note is assigned by which clef could be clearer than the last-minute insistence on "particular G's C's and F's" which are, I think, confusing.

You might compare the German and French pages on Clefs for some good solutions to this problem (Fr. Clef, Gr. Notenschlüssel), and hopefully a more clear wording will be able to be reached by consensus.

Also, I think the historical note about the shapes of the clefs deriving from letters ought to be reserved for a Historical section, where the topic might be expanded upon (the German page is good for this, too).

--Gheuf 01:36, 8 January 2007 (UTC)

Since I had no reply, I went ahead and restored a hopefully clearer version of the introductory paragraph. (Evidently someone else agreed that the one that was up was unclear, since there is now a big sign on the top of the page saying it needs to be "cleaned up".) Obviously it is still somewhat clumsy and I look forward to others' corrections.

--Gheuf 07:04, 13 January 2007 (UTC)

Re: "1. A clef does not assign names to the lines and spaces of the staff, but assigns A name to ONE line. (The other lines and spaces following from this of course.)" I don't see the distinction you are attempting here. If you put a G on the second line of a staff, you do it not just to assign the G note to that line, but to assign letter names to all the lines and spaces of the staff. TheScotch 07:36, 13 January 2007 (UTC)

Re: "Each clef assigns some particular note:" I think you mean octave, not note. Historically, octave assignment did come later. TheScotch 07:36, 13 January 2007 (UTC)

Re: "Also, I think the historical note about the shapes of the clefs deriving from letters ought to be reserved for a Historical section, where the topic might be expanded upon (the German page is good for this, too)." It might be elaborated upon in an historical section, but it needs to be mentioned immediately in the introductory paragraph because it is impossible to explain what clefs basically are without it. TheScotch 07:36, 13 January 2007 (UTC)

Re" "Obviously it is still somewhat clumsy and I look forward to others' corrections." No, it is much more clumsy now--and awkwardly written and dumbed-down. TheScotch 07:36, 13 January 2007 (UTC)

Sorry, I did not see these or I would have replied earlier. I've made some changes recently which hopefully will show what I meant more clearly than an explanation here could.

Of course you are right that the clef determines the names of all the lines and spaces of the staff, not just of one line. But the distinction is, that the purpose of the clef is to label ONE line directly: the other lines and spaces are named by inference. Similarly, if I had a series of files each corresponding to a year, I could label each one directly (2004, 2005, 2006, etc.), or I could label one reference file and allow the other years to be determined by inference by relying on some convention (perhaps, that later years are always BEHIND earlier years).

This distinction is important only because it makes the definition of "clef" easier. An F-clef is derived from the letter F and is used because it indicates the note F and labels one line of the staff as belong to that note. Yes, it is true that it also assigns all the other notes by inference -- nevertheless it is an F clef, so called because it indicates the note F (in particular, the F below middle C). Historical information should not be necessary to explain the concept of a clef if this distinction is taken into account.

The only purpose for this splitting of hairs is to allow a more rational and tidy presentation in the article. Let me know what you think of my recent changes.-Gheuf--70.107.173.227 16:19, 18 January 2007 (UTC)

On the whole the article is better, I think. I'm not happy with the current opening sentence, though: "A clef (from the French for "key") is the one musical symbol that allows you to indicate the pitch of written notes." I'm not even sure I understand it. Why "the one musical symbol"? What are we saying here? TheScotch 06:13, 20 January 2007 (UTC)

- Originally the introductory paragraph opened with a definition of "clef". Of course, I still have that, and in, I think, simplified terms. But I tried to add to the paragraph something that would help someone who came to the article with NO IDEA what a clef is. For him, the details of the definition would be confusing without some idea of why we NEED a clef. For that reason, I decided to open the paragraph with a statement of the PURPOSE of a clef -- it is not some fussy thing about assigning names to lines: it is a very useful part of music ntoation. It is the only symbol whereby pitch can be represented! That is why it is "the one musical symbol" -- what other symbol can be used to indicate pitch?--Gheuf 04:47, 23 January 2007 (UTC)

- Wahoofive agrees with you that the opening sentence was unsatisfactory. He has amended it with the note "more clarity of intro". I do not think, however, that the new sentence is better and I think we should continue to work on hammering out a good concise opening (which is much trickier than it might seem).

- Wahoofive's new version reads: "A clef... is a musical symbol that establishes the relation between written notes and the lines and spaces of the staff." This no longer has the purpose of introducing a totally ignorant person to the concept and usefulness of a clef. Instead of indicating the basic purpose of the clef (notating pitches) it presents a complex idea about the "relation" between notes and the staff. While this may be how the clef works, I think the workings of the clef are sufficiently described in the rest of the paragraph; and if they are not, the new material should be added there. The first sentence should be spare and introduce with maximum generality the concept of a clef and why it is used.

- In any case, I do not think the new sentence even provides a correct description of how a clef does work. What is the "relation between written notes and the lines and spaces of a staff"? Either the note is on the line, or in the space, and that's that -- there is no need of a clef to establish this relation. Even if the sentence could be tweaked to describe the function of a clef correctly, it would still employ terminology inconsistent with that used in the rest of the article. Elsewhere, terms such as "indicate a pitch" or "assign a pitch to a line" are used -- these terms are often used in books and articles on clefs. The word "relation" is not followed up in the rest of the article, and so should probably not be introduced in the opening sentence. To the extent that it is useful, it merely anticipates in an awkward way information that will be presented later in the article.

- Since the earlier version was unsatisfactory, a new sentence should be devised that will fulfill the function described above without the confusion or awkwardness that were felt to tarnish the original. I propose something simple, like "A clef is a musical symbol used to notate pitch."

- We may compare the opening of the article Clef by H. C. Deacon in the Third Edition of the Grove (the only edition to which I have immediate access): "Clef, i.e. key, the only musical character by which the pitch of a sound can be 'absolutely' represented."-Gheuf--70.107.173.227 04:15, 25 January 2007 (UTC)

- I had your comments in mind when I was writing, but I don't really agree that pitch has anything to do with it, except in a very indirect way. Indicating that the second line is G doesn't necessarily attach that note to a pitch, per se, due to variations in tuning systems, lack of historical standardization of pitch, and transposing instruments. When a French horn plays in treble clef, the clef makes the second line mean G, but that relates to some other pitch.

- As I have mentioned on several pages, it's a tricky balance between providing a simple explanation like a 3rd-grade piano teacher, and providing a truly accurate reflection of a deeper understanding of the possibilities. It's like explaining gravity -- you want to be comprehensible to average people while still remaining true to the theory of relativity. The more you learn, the less you know. —Wahoofive (talk) 05:44, 25 January 2007 (UTC)

- Thanks for the response. I see your point about pitch, but I think that nevertheless the current wording cannot stand for the reasons given above. The first sentence should as you say be accurate, and I am not sure that it is now. It should also be simple, in that it should distill any "deep understanding of the possibilities" into an elegant summary accessible to anyone. Any complications should be presented later on in the article. Besides, the complications you raise have more to do with the definition of what 'pitch' is than of what a 'clef' is. Maybe these distinctions should be given at 'pitch', which will, after all, be hyperlinked.

- The transposing instruments are a special case, best discussed in their own article.

- Of course, there are a number of ways of phrasing these issues. If standard reference works describe it in one way, it might be best to follow their example, rather than invent our own philosophy.--Gheuf 06:10, 25 January 2007 (UTC)

- Fair enough. The only standard reference work I have handy is the Harvard Dictionary of Music, which says "Clef: a sign written at the beginning of the staff in order to indicate the pitch of the notes." Point to you. Nonetheless I think we're evading our responsibility to use terms accurately if we use "pitch" without regard to its distinction from "note". The clef makes an association between the staff positions and the note names; pitch isn't really involved. I agree that the new opening sentence I wrote isn't perfect; by all means improve it. —Wahoofive (talk) 07:36, 25 January 2007 (UTC)

- OK but before I do I want to make sure I understand the objection. Further along in the paragraph it says that the clef assigns "a name and a pitch" to the notes on its line. If I understand you right, you would like to see "name" retained but "pitch" stricken, because there is a difference between pitches and note(-name)s. What exactly is this difference?

- To take a stab at this philosophizing, I suppose we could say that the word "note" is used in three senses, to refer to: 1. a written sign 2. a concept 3. a sound. In its third sense, I think "note" might be synonymous with "pitch". Even if historically the conceptual "note" (2) has been assigned to various sounding "notes" (3), I think that it is acceptable to conflate the two in this article.

- To avoid this conflation, the first paragraph might be revised to read: "A clef is a musical symbol that assigns a name to the notes on the line of the staff on which it is palced." This would be correct, but, I am afraid, would make the casual reader say: "Why do notes need names?" Surely they need names because the names indicate a pitch (higher or lower?). This is the basic reason why we need clefs and I think it only fair to introduce the article with a simple idea like that. --Gheuf 18:51, 25 January 2007 (UTC)

- OK, so I've tried a compromise measure. The opening sentence now says that the clef indicates the pitch of notes, but, in case "pitch" be understood in the wrong sense, I've provided a footnote which, I believe, makes the distinction you requested.--Gheuf 19:43, 26 January 2007 (UTC)

The footnote strikes me as very clumsy, and I don't think there's any point in giving the etymology of clef unless you explain in what sense a clef is a key. TheScotch 08:15, 28 January 2007 (UTC)

Tenor Clef

An old description of the uses of the Tenor Clef has been restored that, in my opinion, reads more as a description of how to notate for trombone and other bass instruments, rather than how to employ the tenor clef. Of course, the tenor clef is employed for the notation of bass instruments, and so the two subjects are interrelated. But the wording should be altered to emphasize the usage of the clef generally -- not the peculiarites of notation for certain instruments in particular (or certain musical traditions, such as jazz). All this info could be included, but in a way that did not throw the emphasis off -- right now the description sounds like an intrusion from another article.

--Gheuf 01:42, 8 January 2007 (UTC)

Look: Since no instrument currently uses the tenor clef as its main clef and since it is utterly pointless to discuss a clef without relating it in some way to some "particular" instrument or instruments, without what you call "peculiarites of notation for certain instruments in particular" we'd be left with no reason for a tenor clef paragraph at all. TheScotch 07:40, 13 January 2007 (UTC)

I think you are right that in the Tenor Clef section we need to discuss certain particular instruments -- you point out (rightly) that if we did not do this the section would be empty! My objection was, that this needs to be done in a way that does not throw the TOPIC of the paragraph off. It was an objection to the STYLE more than to the CONTENT of the paragraph. As I said, the paragraph reads like a description of trombone notation, not like a description of the uses of tenor clef. This does bring in the Content to a certain degree: why remark that the trombone uses the treble clef? This may be TRUE, but it s not pertinent to the TOPIC: which is, not every clef that may be used for the trombone, but rather the tenor clef in particular.

--Gheuf 19:07, 13 January 2007 (UTC)

The point is simply that the trombone does not necessarily use the tenor clef (in its higher range)--specifically, it doesn't use the tenor clef in jazz scores. It would be misleading not to mention this--if you're going to mention the trombone in connection with the tenor clef at all, that is, and I think you've just agreed that we do need to mention the trombone in connection with the tenor clef. TheScotch 06:25, 20 January 2007 (UTC)

"totally obsolete"

Re: " 'Totally obsolete' contrasts with 'obsolete except for transposition' " The phrase "totally obsolete" sounds to me like teen-age slang rather than the sort of formal diction appropriate for an encyclopedia. "Completely obsolete" would be better--except that, as I've already pointed out, it's redundant: a practice is either obsolete or it isn't. If the inconsistency bugs you, merely rephrase "obsolete except for transposition". (This is assuming we even want this transposition business at all, and I happen to think we shouldn't--no more than the silly list of mnemonics.) TheScotch 07:48, 13 January 2007 (UTC)

I would be fine with "completely obsolete" rather than "totally obsolete", but I do not think it is necessary. In this context, the two words seem to me entirely synonymous. I am familiar with the teenage use of "totally" you refer to (where "totally" means something like "I am surprised to say" or else "very much so"), but I do not think that the existence of a slang usage must necessarily oust the standard usage, or that any real confusion is possible in this case.

As to the idea that, by definition, there can be no degrees of obsolescence, I would argue that insofar as your claim about the word is based on the way it is used in the world, the case in question ought to act as a counterexample to that claim; insofar as you intend to establish the true meaning of the word "obsolete" by fiat, there is, of course, no argument possible.

Gheuf 19:19, 13 January 2007 (UTC)

I'm sorry, but it is necessary to make a distinction between informed literate speakers of English and teenage slang mongers. It is not, however, necessary here for the philologists to wage war with the soi-disant "descriptive linguists" (imagine a pronunciation dripping with irony)--time and space do not permit this, and it's fairly tangential anyway. For the purposes of this article, let's simply agree to define obsolete to mean not currently used for writing new music. TheScotch 23:08, 19 January 2007 (UTC)

I wrote the above without having re-examined the current status of the article--pressed for time, sorry. It appears a moot point now. TheScotch 06:06, 20 January 2007 (UTC)

Absolute pitch?

- These clefs developed at the same time as the staff, in the 10th century. Gregorian chant used moveable "Do"- and "Fa"-clefs on its early four-line staff. As chant notation used only relative pitch, they represented only the respective tones. These clefs became, respectively, the C- and F-clefs in modern music after absolute pitch was notated.

Who wrote this travesty? Standardized pitch came about centuries later than modern clefs; and anyway, if you consider transposing instruments, modern clefs still only represent relative pitch (and don't even get me started on A-415). And why is the lack of absolute pitch even relevant? Those Gregorian clefs meant exactly the same thing as their equivalent modern clefs. —Wahoofive (talk) 21:34, 17 January 2007 (UTC)

Don't know who put that in there but I agree that it needs to be reworded. As currently worded, the passage does not make clear what the relation is between the development of the notation of absolute pitch, and the development of the C-clef used for Gregorian chant into our modern C-clef. What does the change of shape have to do with the change of function? Probably nothing, as you say. Transposition, though, is a whole 'nother story: the fact that some instruments are transposing instruments does not suggest that our current notational system uses relative pitch: in fact, it implies the exact opposite, since if the notation only indicated relative pitch, then the concept of "transposing" would not have any meaning.--70.107.173.227 05:56, 18 January 2007 (UTC)

Um..."relative" in a different sense, I think. Strictly speaking, "transposing instrument" is a misnomer: There is nothing "actual" about concert pitch; it just happens to be different from the horn's, for example. Nowadays pitch is relative to the instrument, but for a particular instrument it is no longer relative. Unfortunately, it is necessary to qualify that last remark too because the horn's middle C still does not necessarily refer to one particular frequency. Aside from the "A-415" mentioned above there is also the ambiguity of different tuning systems. Nowadays pitch is relative to the instrument, but for a particular instrument it is relatively no longer relative. Ouch. TheScotch 06:36, 20 January 2007 (UTC)

No, I'm sorry, but Wahoofive is simply wrong. There is a fundamental difference between the 'modern' use of clefs to indicate pitch - however rough and ready, TheScotch - and the use in Gregorian chant to indicate the intervals between notes. A Gregorial F clef said nothing about the pitch; it could be used for any voice or any instrument, high or low. It indicated that interval with the next note down was a semitone, and that the interval between the notes two lines higher and two spaces higher was also a semitone. 84.67.16.111 (talk) 23:55, 2 December 2008 (UTC)

- Modern clefs may mean that also, for example when a round or canon is notated, which can often be sung or played at an arbitrary pitch. Don't forget that "modern" clefs developed directly from Gregorian clefs and there is no historical dividing line. Although now in the 21st century we think of clefs as representing specific frequencies, "modern" isn't being used with that meaning here. —Wahoofive (talk) 18:33, 3 December 2008 (UTC)

"Remaining" Clef Letters

Re: " 'Remain' suggests that in former times some other clef letters were used -- this suggestion would only be appropriate if it were followed up with a historical digression (on the '"gamma'" perhaps)" F, C, and G are the only clef letters ever widely used, but in theory any letter could have been used--which needs to be emphasized to make the nature of the clef system clear, and in practice other clef letters were, just not widely enough ever to be accepted as any sort of standard practice--which is why it was necessary to whittle down the clef letters, and eventually their placement. TheScotch 23:03, 19 January 2007 (UTC)

- In the Historical section it now says that formerly the D- and Gamma- clefs were used. Any other discussion of such truly obsolete clef symbols should, I think, be added in that section, and not at the top, where a definition and overview are required without veering off topic.--Gheuf 01:24, 20 January 2007 (UTC)

I've seen a b-moll clef in plainchant; i.e. a symbol like a modern flat sign on the intended b-line, but that was in a modern transcription which claimed to be 'authentic' - whatever that means - so perhaps someone knows if that was a mediaeval usage? OldTownAdge (talk) 21:46, 3 April 2009 (UTC)

Images

I tried to clarify the opening paragraphs, and removed the cluttering references to transposition, as requested. I also tried to fix the historical section. Along the way, I added an image for every clef. Unfortunately, the images came from different sources and do not match. If anyone has access to a program like Sibelius, I think the page would look better with matching clefs.--Gheuf 08:37, 18 January 2007 (UTC)

Wikify/Cite Sources

Can these be removed? I think the issue of "wikification" has been addressed with the reformatting of the article. As to "cite sources", I'm not sure I understand what passages really need citing. The page is a simple description of how clefs work, which is common knowledge to all musicians. I don't see what neeeds to be cited.--Gheuf 18:43, 25 January 2007 (UTC)

- I managed to find a complete matching set of images on the Polish clef page -- apparently they were originally here since they were all named in English. They look good together, but unfortunately each image has a lot of extra blank space on the top of it which prevents it from lining up properly with the text. If anyone is good at editing images I wish they would delete that extra space.--Gheuf 18:52, 26 January 2007 (UTC)

Please define placing a clef "on" a line

As the clefs obviously span all or most of the lines in the staff, it's important to define what it means to place a clef "on" a line. For example, it should be noted that placing the F clef "on" the fourth line means that the fourth line passes between the two dots. Kdietz 17:40, 26 January 2007 (UTC)

- OK, I added a description of what it means for the clef to be placed on a line in the table in the first section. I'm not sure I like how it looks however. Surely the meaning of "placed on a line" can be inferred from the exhaustive examples given in the section "Individual Clefs"?--Gheuf 18:24, 26 January 2007 (UTC)

"What it means to place a clef 'on' a line [or space]" has to do with the original system and cannot be divorced from it. In the old days clefs were visually indistinguishable from plain old ordinary letters. These letters were not huge compared to the staff, and it was very easy to see immediately to what line or space they were pointing. It's not at all obvious to what line a modern treble clef, for example, is pointing and this is why I immediately and very briefly and succinctly explained the original system in the opening sentences I wrote, which Gheuf subsequently replaced. TheScotch 08:33, 28 January 2007 (UTC)

- I agree that it is not obvious to which line the current clefs are pointing, and that when clefs were still written just like their letter-names it was easier to tell which line they were associated with. But does knowing that the G-clef used to be written like a G help us figure out which line the modern, curly, enormous G-clef points?

- Hopefully the new colum in the table will help with this problem. It lists, separately for each clef, how you can tell which line it is pointing to. This is just like the old version of the article, where this information was given under each separate clef heading (and not in the introduction).

- The introduction to the old version did, it is true, say that the clefs came from letters: but it did not help you figure out which lines the modern clefs are pointing to. I'm sorry your original sentences got lost -- obviously I have no way of knowing which were yours. But the opening paragraph as I encountered it did not really address this particular problem.

- "A clef (also, in former times, cleff) is a musical notation symbol that assigns note letter names to lines and spaces on a musical staff. The term derives from the French word for key--not in the sense of key signature, but in the sense of key to the puzzle. The idea is that if you know the clef letter, you can interpret a note on any line or space between two lines simply by counting up or down to it alphabetically. If, for example, we assign the note G above middle C to the second line from the bottom of a staff, then we can easily determine that the first space from the bottom on this staff represents an F, that the first line represents an E, and so on.

- "Three clef letters remain in modern music notation: G, F, and C. These clef letters were once written plainly, but over time became more ornate until they eventually came to resemble alphabetical letters only vestigially. The term clef is used equivocally to refer both to clef letters themselves and to particular placements of clef letters: We speak of both the C clef in general and of its placement on the middle line of a staff which we call the alto clef. Clef letters always refer to particular G's, F 's, and C 's, namely the G above middle C, the F below middle C, and middle C itself, respectively."

- --Gheuf 04:43, 29 January 2007 (UTC)

- I'd say the fact that a clef resembles a letter which points to a particular line is not really important enough to make the opening paragraph, though it obviously belongs in the article. Perhaps we can find a way to define what a clef is without that particular detail. A clef defines the relationship between the staff positions on a particular staff and the series of notes which comprise the musical gamut.

- I would like to note, however, that putting something "on a line" often confuses beginners. When you write words "on the line," than means the letters go above the line. In music, it means intersecting the line. —Wahoofive (talk) 06:40, 29 January 2007 (UTC)

- That's a good point you raise: in a sense,when we say "on a line" we use the word "on" in the opposite of its usual sense. This is true of notes, too, and not just clefs. (A note on a line in music is not resting upon a line (that would be "in a space") -- it is straddling across it.)This should probably be covered in the article "staff" more clearly.

- Currently, the information about letters which the clefs only vaguely resemble but from which they historically derive is given in the "historical" section. --Gheuf 15:03, 29 January 2007 (UTC)

Why are clefs called "clefs"?

TheScotch has requested that somewhere in the article (prefereably in the first paragraph) an explanation should be given of why clefs are called "clefs" ("keys"). But while it is easy to see that the English "clef" comes from the French word for "key", it is not easy to see why this designation should have been chosen.

I have been doing some informal research through Google and was able to find two 16th-century treatises on music in Latin here and here, one by Heinrich Faber and the other by Janos Czerey. Both texts are in question-answer format for beginning students, and both subdivide music into five parts: clavis, vox, cantus, mutatio and figura. The part that concerns us is "clavis", the origin of our word "clef".

It seems from looking at these treaties that the word "clavis" was used to refer to the letter-names of the notes (as opposed to the solmization names, which were the "voces"). Faber says that there are 20 "claves" and provides a diagram of "what is vulgarly called the scale": this is the Guidonian scale starting at Gamut (the low G which we write on the first line in the bass clef) and going up to "ee", which we should write on the fourth space in the treble clef. (There are 20 "claves", instead of only 7, because Faber counts separately each of the three octaves then used.)

Czerey also says that there are 20 "claves", but that "essentially, there are only seven, corresponding to the seven letters A B C D E F and G", because of octave equivalency.

From this it should be clear that "clavis" used to mean the letters by which we refer to notes. This is confirmed by Rousseau in his Dictionary of Music, where he says "Anciennement on appelait clefs les lettres par lesquelles on désignait les sons de la gamme. Ainsi la lettre A était la clef de la note la; C, la clef d'ut; E, la clef de mi, et cetera." [Formerly the letters by which the sounds of the scale were designated were called "clefs". So the letter A was the clef of the note la; C, the clef of ut, E, the clef of mi, etc.]

Why were the letters called "keys"? Czerey writes: "What is a clavis? - It is the unlocking of the cantus. Why are they called so? - Because they are enclosed [clauduntur] by a line or a space, or because they unlock what is hidden and unknown to us, namely the 'voces', 'cantus' and 'toni'." Faber says merely, "What is a clavis? - It is an indication of how the 'vox' is to be formed." Obviously even they did not know why the letters were called keys.

It is easy to guess from the above how the "claves", when placed at the front of the staff, became our "clefs". In the period, these letters at the beginning of the staff were called "claves signatae", that is "designated keys" or "clefs" as we may now call them. At the time, in addition to the F, C and G clefs, Gamma and D clefs were also used. Here is Czerey: "How many are the claves signatae? - They are 5. [Gamma] F c g [and] dd. Why are they called signatae? - Because they alone are placed in the cantus, and by them the other [claves] are measured.... Moreover, we in our cantus generally use only two claves signatae: F..., and c..., sometimes Gamma, too, but rarely, and g extremely rarely, dd scarcely at all." And Faber says: "How many are the claves signatae? - Five. [Gamma] ut, F fa ut, c sol fa ut, g sol re ut, and dd la sol. Why are they called signatae? - Because only they are expressly put at the beginning of the cantus."

Rousseau gives a bit more detail, but thinks that only four claves signatae were used: "Gui[do] d'Arezzo, qui les avait inventées [les clefs], marquait une lettre ou clef au commencement de chacune des lignes de la portée; car il ne plaçait point encore de notes dans les espaces. Dans la suite on ne marqua plus qu'une des sept clefs au commencement d'une des lignes seulement, celle-là suffisant pour fixer la position de toutes les autres selon l'ordre naturel. Enfin, de ces sept lignes ou clefs, on en choisit quatre qu'on nomma claves signatae ou clefs marquées, parce qu'on se contentait d'en marquer une sur une des lignes, pour donner l'intelligence de toutes les autres; encore en retrancha-t-on bientôt une des quatre, savoir, le gamma, dont on s'était servi pour désigner le sol d'en bas." [Guido d'Arezzo, who had invented the clefs, designated one letter or clef at the beginning of each of the lines of the staff; for he did not yet put notes in the spaces. Subsequently, only one of the seven clefs was designated at the beginning of only one of the lines, which was enough to establish the position of all the others according to the natural order. Finally, of these seven lines or clefs, four were chosen which were named claves signatae or designated clefs, because it was found satisfactory to designate one of them on one of the lines, to give knowledge of all the others; soon one of the four was expunged, namely, the gamma, which had been used to indicate the low sol.] --Gheuf 21:38, 29 January 2007 (UTC) --24.199.120.71 20:49, 29 January 2007 (UTC)

These are modern sources, though, in the sense that all of them are far nearer our time than the time of the invention of clefs. Surely it is unlikely that the word is distinct from 'key', especially as they functioned as key-signatures rather than pitch indicators in the early period. OldTownAdge (talk) 21:51, 3 April 2009 (UTC)

Change in Format

I reformatted the clef categories. Is this format allowed to be on Wikipedia?--74.103.11.210

- Looks fine to me. Don't know if it's allowed, but I can't see why not.--Gheuf 00:51, 31 January 2007 (UTC)

New Images

The Image showing all the clefs looks great, but the one at the top of the page is weird. The notes are not the right shape. (The black notes have the shape of whole notes....) It makes them look pudgy. Can this be fixed?--Gheuf 18:38, 19 May 2007 (UTC)

Violin clef = main clef?

The page now reads "[the treble clef] was formerly known as the violin clef or the main clef". Is this really true? I have never seen that name.--Gheuf 00:16, 7 July 2007 (UTC)

Probably a dumb question

This sentence is from the paragraph on 'The Alto clef'. "It occasionally turns up in keyboard music to the present day (Brahms' Organ chorales, John Cage's Dream for piano)."

I'm wondering - does the mention of Brahm's organ chorales mean they are "present day" or does it refer to modern day transcriptions of these chorales?

- The original ed. w/ alto clef of the Brahms is still in print and used by many performers, though there are now competing editions with G/F clefs only. Sparafucil 10:22, 2 October 2007 (UTC)

- Thank you. Wanderer57 23:27, 2 October 2007 (UTC)

- - - -

The people responsible for this article should be very proud of it. It is a clear, readable and visually attractive presentation. Wanderer57 18:28, 30 September 2007 (UTC)

Stylistic Issues/Typos

I'd suggest a few minor changes:

1. (History section) Several variant shapes of the different clefs persisted until very recent times. The F-clef was, until very recently, written... Can this be redone without repeating a form of the word recent?

2. (History section) Alternatively, is reduced to two staves, one with the treble and one with the bass clef. Is this sentence missing a word or phrase after Alternatively?

3. (Further Uses section) One more use of the clefs is training in sight reading... Why not Another use..., using one word where two appear now? Savacek (talk) 03:37, 29 March 2008 (UTC)

Double Clefs?

I'm somewhat of a music theory novice and am reading the Fux counterpoint book. Throughout the examples, there are two clefs on each line, starting with a C clef that tends to change position across examples, immediately followed on the right by a double vertical line, and then a treble/G clef. The treble and G clef positions seem to contradict each other, so I am totally confused. Is anyone familiar with this notation? It would be great if there were a section in the article that covered this notation. —Preceding unsigned comment added by Jaxelrod (talk • contribs) 15:07, 6 July 2008 (UTC)

This is used in modern editions of old music. The C clef indicats the clef used in the original edition (sometimes also followed by the range of the part as it appears using that clef) and the G or F clef is then used because they are the more common ones nowadays. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 67.111.160.114 (talk) 17:07, 3 September 2008 (UTC)

On the topic of Double Clefs, however, sometimes you'll see a double treble clef, one after the other (Sometimes intertwined). This is to be played an octave lower than a single g-clef staff would be played. Should this be included on the main page? Leemute (talk) 18:29, 23 April 2009 (UTC)

Clef vs Staff

I guess I'm a little old school in my terminology but the terms clef and staff seem to be used interchangeably here.

I was taught (according to Nadia Boulanger who was very strict and demanding) that a C-clef is a C-clef is a C-clef. There is no tenor clef or alto clef. It is only when the clef is placed on a staff that you create a tenor staff or alto staff or mezzo-soprano staff.... Granted, that is not casual usage, but would it help to adopt this more precise defintion in this article? DrG (talk) 13:45, 28 October 2008 (UTC)

G-clef = Sol-clef?

In the History section towards the end of this entry this statement is to be found: "In other words, the reason that the G-clef looks the way it does is likely that it is a drawing of a very fancy letter S..." Now, flourish at the top notwithstanding it seems pretty glaringly clear from looking at a history of the clef's gradual evolution that it came from a G. Perhaps some of the sinuous appearance at the top of the modern Treble clef came from an attempt to infuse some "Sol-ness" into the obviously still G-shaped clef, but to say that it evolved from an S seems very misleading at best. Changchub (talk) 03:25, 16 March 2010 (UTC)

- The article cited is Kidson [1] subscription access) who argues that the G clef, arising in the 16c is an abbreviation of "G-sol" and combines the two letters G & S. I cant say how conclusive his fig. 1 is; New Grove only says maybe. Sparafucil (talk) 08:04, 16 March 2010 (UTC)

Do we need to name every note on each staff?

Each clef has a line of nine pitches associated with it, naming the notes from bottom line to top line, with the reference note in bold. I don't see the reasoning for having other notes in bold text. For that matter, I am not sure we even need the line of nine note names at all. Keep them all, lose them all, keep/lose a selected few, or what? Comments? __ Just plain Bill (talk) 21:41, 15 April 2010 (UTC)

Here is the diff. __ Just plain Bill (talk) 21:46, 15 April 2010 (UTC)

- I'd vote for eliminating the note names altogether - it strikes me as clutter. As a musically literate person, I may be biased and not representative of the target audience, though. - Special-T (talk) 04:17, 16 April 2010 (UTC)

- I'd be willing to spend some time massaging the SVG images to lose the Helmholtz notation, and label the reference line with something other than a note head. I agree that it is cluttered with a line of text detached from the related staff/clef image. How do folks feel about labeling each staff completely, right there in the image? I'll pop an example onto this talk page as soon as I come up with something, but RL is demanding just now, so it might be a few days. __ Just plain Bill (talk) 14:03, 16 April 2010 (UTC)

Here are some possibilities. I favor the first one as clearest and simplest. Easy enough to modify any of them-- open to suggestion. __ Just plain Bill (talk) 15:07, 17 April 2010 (UTC)

First one, definitely. I'm all for more simple clarity in wikipedia! Anyone who knows the letters A through G can deduce all other notes in a few seconds. - Special-T (talk) 22:09, 17 April 2010 (UTC)

History

I think a history section would be a great addition. I came looking for why the clefs are shaped like they are. If you guys have any references for it could you add a bit of background to the article? Thanks! --CyHawk (talk) 09:43, 23 May 2010 (UTC)

Images

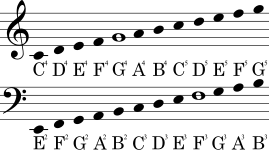

There are currently two images at the top of the article:  and

and  . The former is completely repoduced in the latter. Why are both needed? I propose de-cluttering the article by using just Bass and Treble clef.svg. Can anyone give a reason for keeping the article as it is? Adzz (talk) 23:19, 15 September 2010 (UTC)

. The former is completely repoduced in the latter. Why are both needed? I propose de-cluttering the article by using just Bass and Treble clef.svg. Can anyone give a reason for keeping the article as it is? Adzz (talk) 23:19, 15 September 2010 (UTC)

- I just removed it, caption and all. If there are objections, here is the place for them... __ Just plain Bill (talk) 02:39, 16 September 2010 (UTC)

C clef bassoon

I play bassoon. A form of the c clef is used. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 76.28.77.142 (talk) 20:45, 15 October 2010 (UTC)

- That c clef is a tenor clef. Please read that portion of the article. Ed (talk) 23:55, 25 December 2010 (UTC)

Diatonic scale on clef

This article has images for diatonic scales on the treble, bass, and 2 of the 5 C clefs. If we can read C clefs, we should be able to upload images for diatonic scales on all 5 C clefs. Just because a clef is rarely used doesn't mean we can't put notes on it. Georgia guy (talk) 13:32, 12 March 2012 (UTC)

- I see your point: it looks very odd to have only some of the listed clefs illustrated with a C-major scale. The images in question (and the accompanying soundfiles) appear to have been created by Hyacinth. Perhaps he can be persuaded to make parallel illustrations for the other C clefs (and French violin clef, the other placements of the F clef, d clef, etc.). Why don't you post a request on his talk page?—Jerome Kohl (talk) 16:52, 12 March 2012 (UTC)

Obsolete?

Numerous clefs are marked as obsolete. Some clefs, such as Clef#Baritone_clef.E2.80.A0, are described: "This clef is no longer used." with this marked {{citation needed}}. Are these obsolete or not? Hyacinth (talk) 08:48, 13 March 2012 (UTC)

- Depends on what one means by "obsolete", I guess. 'No longer in common use' seems more accurate at least, if no more precise. Sparafucil (talk) 21:34, 13 March 2012 (UTC)

- Yes, indeed. It also depends on whether you are referring to printed music, or as a (mental) transposition device. That was a good thought, Sparafucil, adding the remark about A clarinets, though my first reaction (as a clarinet player myself) was to object that this really was meant to apply not to the soprano clef, but to the tenor clef (used to read A clarinet parts on the B-flat instrument), or the alto clef (used to read B-flat parts on the A instrument). I have amended the passage in order to clarify the usage.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 22:36, 13 March 2012 (UTC)

- (Lol) Fair enough! Sparafucil (talk) 05:52, 14 March 2012 (UTC)

- It strikes me that the combinations G2-F3 & C1-F4 (this convention of clef-name/line-name is common enough for readers to become potentially confused by the article's use of Scientific pitch notation) favored in Bauyn manuscript and Chambonnieres's publications may not be particular to French baroque: the latter I first learned from the Notebook for Anna Magdalena Bach. From my meagre exposure to facsimile editions of English keyboard music I gather G2-F4 was usual, but do you have a perspective on other countries? Sparafucil (talk) 06:08, 14 March 2012 (UTC)

- Certainly the combination C1–F4 was common for keyboard music in Germany. Many Bach manuscripts are notated this way and, IIRC, the keyboard pieces published in Telemann's Getreue Musikmeister and Essercizii musici use this configuration (I can verify this against the facsimile copies of both collections that I own). There are one or two examples in the Well-Tempered Clavier where Bach effected a transposition from a common key into a less common one by striking over the original C1–F4 clefs with G2-F3 and changing the key signature. I know that Bach sometimes notated polyphonic organ music in "open score" with as many as four different clefs, and I am given to understand that this was common practice amongst German organists in the early 18th century.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 16:39, 14 March 2012 (UTC)

- Yes, indeed. It also depends on whether you are referring to printed music, or as a (mental) transposition device. That was a good thought, Sparafucil, adding the remark about A clarinets, though my first reaction (as a clarinet player myself) was to object that this really was meant to apply not to the soprano clef, but to the tenor clef (used to read A clarinet parts on the B-flat instrument), or the alto clef (used to read B-flat parts on the A instrument). I have amended the passage in order to clarify the usage.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 22:36, 13 March 2012 (UTC)

Sopranino clef

Does the term "sopranino clef" have any actual use?? Georgia guy (talk) 00:23, 21 March 2012 (UTC)

- Do you know, I was wondering about this myself. For that matter, I think it would be a good idea to discover when the names "alto", "tenor", "mezzo-soprano", and so on were first used to describe the various positions of C-clefs. I'll bet it wasn't that long ago. (I have never come across this terminology in the theory treatises of the 16th century and earlier, for example.) Of course, just because you and I have never heard the expression doesn't mean no one has ever used it.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 02:00, 21 March 2012 (UTC)

- A brief search of Google Books turns up plenty of references to "alto clef" and "tenor clef" in the 1700s, but I couldn't find any references to "sopranino" in any time period. Charles Burney (1789) refers to the "counter-tenor clef". —Wahoofive (talk) 16:09, 23 March 2012 (UTC)

- This confirms my entirely unscientific observation, and thank you for drawing attention to the alternative term "counter-tenor clef", which I had not encountered before today.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 16:34, 23 March 2012 (UTC)

- A brief search of Google Books turns up plenty of references to "alto clef" and "tenor clef" in the 1700s, but I couldn't find any references to "sopranino" in any time period. Charles Burney (1789) refers to the "counter-tenor clef". —Wahoofive (talk) 16:09, 23 March 2012 (UTC)

File types

Shame all those files are in .mid instead of .mp3. Rayne117 (talk) 15:50, 10 April 2012 (UTC)

- Wikipedia uses the Ogg Vorbis format, developed by Xiph.Org, for audio. The Ogg Vorbis format is not encumbered by patents, an issue which prompted the decision that MP3 files will not be hosted at Wikipedia.

- __ Just plain Bill (talk) 17:12, 10 April 2012 (UTC)

Defense of clefs

These days it seems en vogue to complain about the number of clefs out there. The primary complaints are a.) that there are too many clefs out there for practicality's sake and b.) that there are no good reasons to use some clefs, like 'C' clef.

Maybe this article could address these criticisms. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 71.232.22.224 (talk) 03:39, 23 October 2008 (UTC)

- Agree. As a musician, I see no point of more than one clef. Absolute pitch could be referenced differently, but there is no need to change the relative position of 'C' in the stave. Mike. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 91.148.87.83 (talk) 15:30, 3 June 2012 (UTC)

- ...talk pages exist for the purpose of discussing how to improve articles. Talk pages are not mere general discussion pages about the subject of the article...

- Having said that, I play both viola and trombone by ear, and sometimes from sheet music written in treble or bass clef. In the case of the treble clef, I often read down an octave, which also works on the cello. I read alto clef with very little fluency, and tenor clef not at all. That does not mean that those clefs are useless; it simply means that I don't need them for the limited range of pieces I attempt.

- Claiming that it is pointless to use more than one clef is ludicrous. Unless there is reliable sourcing for anon 71's assertion, now nearly four years old, that "it seems en vogue to complain about the number of clefs" I'd like to see this topic closed and collapsed. __ Just plain Bill (talk) 14:43, 4 June 2012 (UTC)

- Whoever truly believes that there is no point to having more than one clef is a musical idiot at best, and clearly does not understand instrument ranges as they relate to note-reading. The alto-clef fits the range of the viola EXCEPTIONALLY well, and there's not really a clef that would work better for the instrument. Changchub (talk) 22:03, 4 June 2012 (UTC)

F clef/bass cleff/the tuba

Will the guardian of this page kindly de-list the tuba as a transposing instrument under bass clef? I changed it from work yesterday and see that it was changed back. Tuba music in bass clef is non-transposing; tubists (and I am one) learn to read and prefer ledger lines. I would refer you to the wikipedia pages on both the tuba and on ledger lines, both of which list the tuba as a non-transposing instrument when the music is written in bass clef. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 69.243.147.154 (talk) 14:01, 13 May 2012 (UTC)

- As far as I know, you are correct, so I changed it. There is no 'guardian' of any page, BTW. Thanks for being civil and posting this on the talk page. - Special-T (talk) 22:56, 13 May 2012 (UTC)

- As the editor who reverted that removal, I had better explain why: there was no edit summary, which made the deletion look like random vandalism. I should have known better (or at least checked some sources), and I apologize for my haste. Widor (The Technique of the Modern Orchestra, trans. Edward Suddard, London:Joseph Williams, 1946 ) in fact says that the contrabass saxhorn (contrabass tuba) is notated as a transposing instrument, but a major ninth above sounding pitch (in the bass clef), not an octave (i.e., in B♭). It seems clear that he is speaking of the practice in French military bands, however, since he also says that only the ordinary bass saxhorn/tuba has found a place in the orchestra (he does contradict this statement with examples from Wagner, however). Clifford Bevan's article on the tuba in the New Grove confirms this supposition. He says, "Tuba parts are usually notated at sounding pitch, but in British brass bands and French bands the tubas are treated as transposing instruments". A little further on: "At the end of the 20th century … British brass bands included two instruments in E♭ and two in BB♭ (reading in transposed treble clef); military bands employed one of each (reading at concert pitch in the bass clef). French and Italian bands also included E♭ and BB♭ tubas, notated in France in transposed bass clef, and in Italy in concert pitch bass clef".—Jerome Kohl (talk) 01:11, 14 May 2012 (UTC)

- Yeah - I checked my orchestration books first, just to be sure. I noticed that it was an experience editor (you) that had reverted it originally, so I knew there wasn't an edit war brewing. - Special-T (talk) 01:42, 14 May 2012 (UTC)

- Sometimes experience can be a handicap. Whenever I see an edit made by a non-registered editor, and without an edit summary, my trigger-finger starts itching. I have seen this so many times that it has become a reflex action to shoot first and ask questions later—not always a good policy. Once again, my apologies to 69.243.147.154.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 01:51, 14 May 2012 (UTC)

obsolete clefs

All of the obsolete clefs need to be grouped together under a "historical clefs" section. TheScotch 07:50, 13 January 2007 (UTC)

I agree. How do you think the article should be organized? (Would we have to abandon the order, currently employed, and discussed earlier on this talk page of

G clefs F clefs C clefs

?)

Also, which clefs should be characterized as obsolete? This is an issue that I have been struggling with and that I do not think that I or anyone else has successfully dealt with in the article. Currently, four clefs are used to write music, the treble clef, the bass clef, the alto clef and the tenor clef. But in conservatories around the U.S., SEVEN clefs are routinely taught for their use in transposition. (Add to these the soprano, the mezzo-soprano, and the baritone clefs.) These clefs are still taught in SCHOOLS, though music is no longer WRITTEN in them. A third class of clefs are totally (and completely) obsolete and are, in any case, hardly ever encountered even in old music: the subbass clef and the French violin clef. Then there is the baritone C-clef, which is in a class apart, being only a redundant doubling of the baritone F-clef. There is also the fact that of the three "extra" clefs taught in schools, hardly any were used to write music after the Renaissance, except the soprano clef which was VERY frequent as long as VOCAL music used the C-clefs (a practise that dwindled away throughout the 19th century, it seems). How to incorporate all this info in a clear presentation? Looking forward to hearing your thoughts. --Gheuf 19:24, 13 January 2007 (UTC)

Partition the article broadly into clefs currently used and historical clefs (only label the latter as such, however; it will be transparently obvious that the former are not merely historical). The former partition will subsume a partioning into clef letters and these will in turn subsume a partioning (in the case of the C clef only) into clef placement. All clefs but the treble, alto, tenor, and bass clefs are obsolete. If you want to mention "transposition" clefs, put these together into a separate section (giving us three broad partitions instead of two) either immediately preceding the historically clefs section or immediately following the historical clefs section. TheScotch 23:02, 19 January 2007 (UTC)

Nobody explained, why all clefs are different? Why was it necessary? One clef with 2 ledger lines can cover 2 octaves. Couldn't they have used just one clef and only reference which register it addresses? Why does F-clef regards to note C as E? Cheerz, Mike. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 91.148.80.202 (talk) 03:03, 28 November 2011 (UTC)

- It would be fairly stupid for different clefs all to be the same, wouldn't it? Difference is necessary for the same reason. One clef with thirty ledger lines can cover nine octaves, So, what is your question? Staves of as many as thirteen lines have been used, historically. They didn't catch on. Can you wonder why? The F-clef does not "regards to note C as E" (assuming that phrase actually means anything). Next question?—Jerome Kohl (talk) 05:04, 28 November 2011 (UTC)

Yes, that "phrase" actually means something, although it seems you can't get it. Point is that there is tone C, and it suddenly becomes E when there is some symbol at the beginning of the staff. That made necessary to bring in another symbol that will point out when it is note C. That's how we got clefs. My question is, why was it necessary to bring in such a complicated semiotics, when there are more simple solutions. Mike. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 195.252.66.180 (talk) 21:21, 30 September 2012 (UTC)

- Life can be so unsettling sometimes. —Wahoofive (talk) 02:49, 1 October 2012 (UTC)

So, you're saying that musicians lack of general knowledge was responsible for this? Mike. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 91.148.83.136 (talk) 14:28, 1 October 2012 (UTC)

- I doubt that is what Wahoofive is saying. Musicians have used what works for them, using a clef that fits the range of the singer or instrument for which a part is written. It isn't all that complicated. __ Just plain Bill (talk) 15:45, 1 October 2012 (UTC)

Oh, I've found the answer. It seems that during the first printing era it was very hard to do the ledgers, so it was common to try to fit all the music inside those 5 lines. That's why we can see a lot of clefs used throughout the history, of which only a couple are left in use today. I'm interested to see when will it all fall apart, leaving only one absolute notation system. Mike. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 91.148.83.136 (talk) 19:21, 1 October 2012 (UTC)

- Close, but no cigar. The proliferation of clefs long predates the advent of printed music, but it's likely the the desire to avoid ledger lines was a big motivating factor. And in an era when music was taught using hexachords rather than scales, and with no absolute pitch, the need to have a standardized system with a one-to-one correspondence between staff positions and notes was far less important.

- Furthermore, limiting the music on ledger lines is still enormously helpful in sight-reading today. Asking a cellist or violist to play music all written on a million ledger lines below the treble staff would make the job much more difficult, so your ultimate goal of getting all music on the same clef is unlikely ever to be realized. —Wahoofive (talk) 19:35, 1 October 2012 (UTC)

Where did you get an impression that I was talking about million ledger line system? It is fine to have clefs indicating instrument like violin, bass or other, but there is no need to have notes transposed. Mike. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 195.252.65.243 (talk) 20:06, 2 October 2012 (UTC)

- Mike, it doesn't appear that you realize that these instruments you mention have dramatically different ranges. It would not be practical to try to use the same clef for all different instruments. Changchub (talk) 10:44, 3 October 2012 (UTC)

It was not my quation about clefs itself, but the relative note transposition of the tones among clefs. Read my first post. Mike. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 91.148.82.241 (talk) 18:07, 7 October 2012 (UTC)

- Instrumental and vocal ranges do not all differ by neat multiples of an octave, so not all of them fit conveniently on a staff with, for example, E on the bottom line and F on the top. Do you have a suggestion for changing the text of the article? __ Just plain Bill (talk) 23:14, 7 October 2012 (UTC)

This question may be somewhat treated like the Dvorak keyboard vs. standard. It's to complex for me to contribute, but I was hoping to find answers here. Hopefully, someone will analyze that thing in the future. Mike. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 91.148.87.89 (talk) 18:37, 11 October 2012 (UTC)

Grand staff "ledger line" C-clef?

I could swear I've seen at least once, but I can't recall where, a C-clef on a keyboard grand staff exactly at an equal distance between the staves and used instead of the usual pair of clefs on respective staves (treble above, bass below). So it wasn't really placed on a ledger line or at the level a ledger line should come, since on the grand staff one doesn't use one ledger line in the middle to indicate middle C but a first lower ledger line below the upper staff and a first upper ledger line above the lower staff at some space from each other (even though they designate the same note). I only call it a "ledger line" clef because it is there to indicate that middle C sits on those two ledger lines, and also because I don't have a better name for it and I don't know what it is really called. Would anyone who's seen this clef also and who's got a source for it (if it really exists and is not just a figment of my imagination) be kind enough to add it to the "other clefs" section? Basemetal (talk) 14:15, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- If I understand you correctly, I have never seen such a thing in actual musical literature, but I am fairly certain I have seen illustrations in theory textbooks where a C-clef is superimposed on a grand staff, in order to show the relationship between F, C, and G clefs—not instead of, but in addition to the two usual clefs. This would not likely involve a "ledger line", as you say, since the presence of the C clef would demand the use of an eleven-line staff. Is this what you are thinking of? Such larger staffs for keyboard music do occur in the historical literature. If memory serves, the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book includes examples with eleven and thirteen-line staffs, but not with a single C-clef at the beginning, I think.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 17:27, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- If you understand that it was not an 11- or 13-line staff, it was a regular piano grand staff, that is two parallel 5-line staves joined by a brace, with the C-clef halfway between the two staves of the grand staff, and no G- or F-clefs present on the grand staff then you understand me correctly. If you've never seen it you're certainly not the only one. I myself have seen it not more than maybe once and definitely not in a regular score. Again, it was not on a ledger-line. I only called it that for the reasons I explained above (and I put ledger-line in quotes). Basemetal (talk) 23:00, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- I assumed when you said "not on a ledger line" that you meant it was on a line (as clefs by definition ordinarily must be), but that it was a continuous one, rather than the "temporary", short ledger line. I have to say that I have never seen this case that you describe. Since you say it was not in a regular score, I presume you must mean it was in a theory book of some sort.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 00:40, 10 November 2012 (UTC)

- A book but not on theory. More likely history of music or maybe a biography. As far as I can remember the picture was a line drawing meant to show a manuscript (so not a photograph). The staff did carry music. The C-clef was drawn like a K. But do not worry about this. If it has really been used anywhere someone will find a source. It's just that seeing how thorough this article was, with information about clefs I never even heard of (3rd space C-clef!), I didn't want to run the risk that it may leave out any clef that has ever been used. But since I don't really have a source I thought I'd just leave a note in the talk page which may jog someone's memory. Someone with a better memory than me that is.Basemetal (talk) 06:37, 10 November 2012 (UTC)

- I just saw in an unpublished file of the owner of the page "Extremes of Conventional Music Notation" that contains several non-standard music notation examples, the mention (not the actual example) of one or several cases of, to quote, "one clef for two staves" in a Pozzoli Solfeggio. It is certainly not the precise example I think I remember because until an hour ago I didn't even know who Pozzoli was, and besides as I remember, it wasn't in a solfeggio. FYI the Pozzoli Solfeggio series were series of solfeggios popular in Italy. A solfeggio in Italy (and France where it is called solfège) is a booklet of about thirty to a hundred pages (never more) with material to teach sightreading, sightsinging and music theory. The Pozzoli Solfeggio series were written by the Italian composer and pianist Ettore Pozzoli. I suspect the owner of the file did not himself see that example, that it was only reported to him and he simply added that observation to the file. If you are the happy owner of a Pozzoli Solfeggio, you might check if you can see anywhere in any of them an example of one key used simultaneously for two staves (forming I assume a grand staff or a system of some kind), and come back here describe what you saw. Signed: Basemetal (write to me here) 20:20, 5 December 2012 (UTC)

- I assumed when you said "not on a ledger line" that you meant it was on a line (as clefs by definition ordinarily must be), but that it was a continuous one, rather than the "temporary", short ledger line. I have to say that I have never seen this case that you describe. Since you say it was not in a regular score, I presume you must mean it was in a theory book of some sort.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 00:40, 10 November 2012 (UTC)

- If you understand that it was not an 11- or 13-line staff, it was a regular piano grand staff, that is two parallel 5-line staves joined by a brace, with the C-clef halfway between the two staves of the grand staff, and no G- or F-clefs present on the grand staff then you understand me correctly. If you've never seen it you're certainly not the only one. I myself have seen it not more than maybe once and definitely not in a regular score. Again, it was not on a ledger-line. I only called it that for the reasons I explained above (and I put ledger-line in quotes). Basemetal (talk) 23:00, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

What does this have to do with the Tenor Clef?

I found this in the 4th line C-clef section: "The double bass sounds an octave lower than the written pitch." What does this have to do with the Tenor clef? Doesn't this belong in the bass clef section? Signed: Basemetal (write to me here) 04:37, 7 December 2012 (UTC)

- If you read a little further back in that same paragraph, I believe you will find that it says, "This clef is used for the upper ranges of the bassoon, cello, euphonium, double bass, and …" (empahses mine).—Jerome Kohl (talk) 05:39, 7 December 2012 (UTC)

Baritone clef: it'd more clearer if...

I don't come here often. I don't know what the pressing issues here are. I find one thing that may be confusing for some: two separate baritone clefs. Of course if you think a little you see the 3rd F clef and the 5th line C clef are exactly the same thing, but howbout someone coming here for a quick encyclopaedic bit of info? Both so called baritone clefs should be in the same section. Furthermore it'd be good to insert an explanation of where one form of the baritone clef is found and where the other. Contact Basemetal here 01:40, 15 February 2014 (UTC) PS: I don't know if to make the "obsolete" dagger part of the section titles (for obsolete keys) was such a clever move. This makes referencing those sections more difficult and the information that those clefs are obsolete can go into the text of the section it doesn't need necessarily to be in the title of the section. Contact Basemetal here 01:59, 15 February 2014 (UTC)

Some inconsistencies

One section name (section "Alto clef") is anchored others are not. There are redirects for some names (for example "viola clef", "treble clef", "tenor clef", "bass clef" are redirects to this page) and not for others. Just thought I'd let you know. Contact Basemetal here 18:44, 15 February 2014 (UTC)

Alto Clef examples

Which edition of John Cage's Dream is written in alto clef? All the ones I have seen are written switching from treble to bass. Célestin le Possédé (talk) 18:26, 20 March 2014 (UTC)

- You've got me wondering too: perhaps I meant Music for Marcel Duchamp from the film Dreams That Money Can Buy. But I can't put my hands on Dream at the moment. Which printing are you looking at? Sparafucil (talk) 19:28, 20 March 2014 (UTC)

The Peters edition I think. It's a pdf. But it would make sense in alto clef for sure. I'll take a look in a library soon. Célestin le Possédé (talk) 23:16, 20 March 2014 (UTC)

1639 tenor clef

Rather than edit the article directly I would like to call question on the statement made in describing the old tenor or C clef that looks something like a #. The statement as it is at this date says that the note in the graphic is a low E. Unless I am mistaken, I believe it is F3 because the center of the clef, two spaces above, is C4 (middle C). Incidentally, I have seen this clef frequently used in printed music for tenor voice into the mid to late 1900s. Since then it seems to have fallen into disuse. This clef is equivalent to the alto or viola clef (C clef) moved up to the space above the middle line of the staff, and I have also seen that clef used for the same purpose. 64.203.113.231 (talk) 05:59, 14 October 2012 (UTC)

- Just to be clear, this is a 1911 encyclopedia article example, describing a piece composed before 1639. Why shouldn't we take it at its word if the caption claims it's 4th line C, even if it looks a bit funny? I don't see what this has to do with the clef article, though. Sparafucil (talk) 22:57, 14 October 2012 (UTC)

- Those 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica examples are often unreliable in just this way. The placement of the clef is ambiguous. The important thing, though, is the date. Placement of a C clef on a space instead of a line is a 20th-century "innovation" of dubious value, for precisely the reason brought up here: the reader is likely to assume the standard practice for all clefs (prior to the introduction of this "tenor clef"), which is that they identify a staff line (not a space) with a particular pitch. In the 17th century there could be no such doubt: the note is an E.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 23:54, 14 October 2012 (UTC)

- This bogus clef was in several early 20c. music fonts, and its meaning is totally ambiguous. I have seen it used for a C4 tenor clef (as the Britannica article implies), as a C3 alto clef (as in the Sacred Harp, Cooper revisions (1902-1960) where it is clearly defined as C3, and as a substitute for the "octavating" treble clef, where it actually indicates the third space as middle C.Finn Froding (talk) 21:51, 27 May 2014 (UTC)

- The font is one thing, the reference to a 17th-century source quite another. Have you ever seen this used for a 17th-century source to indicate octavating treble clef?—Jerome Kohl (talk) 22:53, 27 May 2014 (UTC)

- No, I don't believe this form of the C clef existed in the 17th century--it's an artefact of the 1911 Britannica. On the other hand, 17th-century the English publisher John Playford was probably the first to use the G2 "treble clef" (instead of the C4 tenor clef) for tenor voices--this allowed the part to be used by treble or tenor singers, whether in a solo aria or in psalmody. Finn Froding (talk) 13:54, 28 May 2014 (UTC)

Thanks for the image of the typical Renaissance C clef. I don't understand why it has a thick horizontal line in the middle, but it's better than anything I could find online. Finn Froding (talk) 22:04, 28 May 2014 (UTC)

- You are welcome. I just looked on Wikimedia Commons and chose the example that seemed most suitable. The centre of the clef is not really a single, thick line, but rather a juxtaposition of the bottom line of the upper "box", the top line of the lower "box", and the staff line passing between them. There is a huge variation in the forms of clefs in early print sources. The one used in the Encyclopedia Britannica is not unique to that source, but is a form found mainly in late-19th-century and early 20th-century prints. I haven't checked, but I think you will find very similar forms in the first edition of Grove's Dictionary. Your information on Playford is interesting. I had never thought about just when this practice began. Certainly the ill-advised attempt to place a C clef on a space instead of a line must be much later. I don't think anyone in the 17th century can have been so stupid. "Octaving" use of clefs of course goes back much further than the 17th century, but only informally. Flutes and recorders, for example, normally played an octave higher than the notation, but this is inherent in the instrumental practice, rather than in the intended use of the notation itself.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 23:55, 28 May 2014 (UTC)