Talk:Varieties of Chinese/Archive 1

| This page is an archive of past discussions. Do not edit the contents of this page. If you wish to start a new discussion or revive an old one, please do so on the current talk page. |

Title

A better title for this article would be "Spoken Chinese: Languages or Dialects?". Linguistic theory about the distinction between "dialect" and "language" aside, the article should focus on the fundamental basis of the controversy -- which has nothing to do with linguistics and everything to do with politics.

All languages evolve over time and, given enough time and geographical distance between varities, they evolve into other languages. So, Latin became Spanish, Aragonese, French, Occitan, Romanian, etc., while Germanic became English, Swedish, Low German, German, Gothic, and so on. Given the length of time involved and the geographic spread of China, it would be absurd to think the Chinese branch of Sino-Tibetan would not evolve to produce new languages, the way every other language family on the globe has done over time. There are, however, some unique factors in the history of China that have made a difference in the evolution of Chinese languages.

First, in the course of the normal evolution of Old Chinese into Middle Chinese into Modern Mandarin, Cantonese, Wu, etc., China became culturally and, more importantly, politically unified long before the one Chinese language did what comes naturally and began to split into varieties that could be distinguished as separate languages. By timeline comparison with the Romance Languages, Chinese political unity under the Han Dynasty happened about 200 years before the Roman Empire spread Latin from Glasgow to Damascus; and while there have been many dynastic changes, the political unity of China has not changed much in the last two millenia, and the core ethnic group of China - whatever language (or dialect) they may speak - still call themselves "the people of Han."

Conversely, the peoples who were conquered by the Romans do not still call themselves "the people of Rome" (if they ever did), but no European governments have ever been successful at enforcing and reinforcing a sense of national and unified cultural identity on the same scale as China.

Second, whereas Semitic and Indo-European languages devised phonetic writing systems based on individual sounds, China - again, during the period when there was still just one Chinese language - began developing and nationally disseminating a logographic writing system that remains logographic today. The advantage of phonetic writing systems is that a small number of symbols can be used in endless combinations to spell any word, whereas logographic systems require learning thousands of characters and combinations. The advantage of logographic systems is that they can be used to represent any language - i.e., you can read Chinese whether or not you speak Chinese; and if you read Chinese, you can also read the Korean and Japanese words written using the logographic system those languages - which are not Sino-Tibetan languages - borrowed from China.

Thus, while there are several different spoken Chinese languages, there is only one written Chinese language. The latter fact did not go unnoticed by early European visitors to China, who initially thought the same words were merely pronounced differently from one part of China to another -- just as the word "tomato" is pronounced differently in different dialects of English (aside: three pronunciations are standard, according to Kenyon & Knott Pronouncing Dictionary of American English - "tuh-MAY-toh," "tuh-MAH-toh," and "tuh-MATT-oh", as nearly as I can render them without using IPA; the third pronunciation is rare, but I have heard it). It wasn't until they noticed the same logographs were used to write Korean and Japanese, etc., that they began to realise there was more to it than that. You can, in fact, use Chinese characters to write English, or French, or Arabic, or any other language under the sun - but that doesn't make those languages dialects of Chinese.

Meanwhile, from the Han Dynasty to the present, the Government of China has always insisted the people of Han all speak the same language; and they have always insisted that language is what the rest of the world knows as Mandarin. China has always taken such steps it has deemed necessary to suppress other Chinese languages, but when you have a logographic writing system that can used to represent that aren't even Sino-Tibetan, let alone Chinese, that becomes an ultimately impossible task. It's a lot easier to police a written language than it is to police a spoken language - in large part, because people can speak more than one language, whether or not they can read and write it (e.g., Low German has had no literature for 200 years, but it is still spoken). And when you use a logographic writing system, they can read and write it - and you the government can't do anything about it, because when the spoken languages are all reduced to writing, it looks like they're all using the same word -- because the common and nationally regulated writing system pre-dates the evolution of Middle Chinese into separate modern languages, so it has always been able to accommodate changes in spoken language while remaining uniform across the country.

Those are the essential points that should be made in the article, I think.

- Is this a POV fork of some sort? What has motivated this article, not to mention a fully bolded link from spoken Chinese? It seems like it belongs in other articles, preferably with less verbose titles. This feels a lot like reading an essay.

Peter Isotalo 00:48, 16 December 2005 (UTC)

- No, this is to avoid cluttering up the "Is Chinese a language or a family of languages?" section in Chinese language with a lot of verbose analogies and comparisons. The bolded link has always been there. -- ran (talk) 00:54, 16 December 2005 (UTC)

- Moved from User talk:Ran:

- Please stop revamping the structure of Chinese language articles with links to a "debate article". Try to solve it within the confines of existing articles. I really thought the section on this in Chinese language fit our needs quite nicely. We don't need full-blown theses-articles on this issue.

- Moved from user talk:Peter Isotalo:

- No, the existing section in Chinese language was verbose, disorganized, disjointed, lacked logical flow, and had a few sections in it that appeared to have been paradropped from other sections. I was spending the better part of the last two hours getting it to read more like an encyclopedia article and less like an aimless monologue. The section was getting ridiculously long anyways, and it is better to provide an overview in Chinese language and details in a separate article, as is customary. Moreover, many articles link to that section, which is not very good Wikipedia practice; it is better to link to a separate article. -- ran (talk) 00:58, 16 December 2005 (UTC)

- The problem might be that there's too much linking to begin with. This problem can be solved simply by mentioning that there is a complication and then settling for that. Transfering the verbosity to a separate article doesn't feel like a good solution to the problem. The title especially feels extremely obscure and elusive and very unencyclopedic.

- Peter Isotalo 01:05, 16 December 2005 (UTC)

- There's a lot of complexity to this issue and it has to be explained somewhere. It can either be explained once in a central location (i.e. here), or ten times in ten different POV, contradictory ways in the Mandarin, Cantonese, Min etc. articles. I agree that the title is not the best and you're welcome to suggest a better one. -- ran (talk) 01:08, 16 December 2005 (UTC)

- I suggest that you take this up in spoken Chinese and link to it when needed. Creating a separate "see thisandthatpage for a more detailed debate"-article seems wholly uncalled for when it's actually about the Chinese dialect-languages, not a subject separate from them.

- Also, please try to keep in mind that most readers aren't quite as caught up in the minutiae of the Chinese dialect/langauge debate as the most active China- or Chinese-editors are and are usually better served with a very brief summary. Most of the time it's enough to write that "opinions on whether Chinese is one language or several differ considerably" or something like it instead of being refered to an all-out explanation on each and every occcasion. Some repetition within articles on the same topic is unavoidable.

- Peter Isotalo 11:23, 18 December 2005 (UTC)

- The see thisandthatpage for a more detailed debate thing has always existed. Spoken Chinese and all of the first level divisions (Mandarin, Wu etc. have always contained a separate link to a debates page. I'm not "creating" the debates arrangement, I'm moving the debate section out of Chinese language to avoid linking to a section within an article. As for the people who aren't quite caught up in the minutiae of the debate -- well, this is an encyclopedia. If they want to find out more about the sociopolitical aspects of the Chinese language then they should get very caught up about the debate. We should be making sure that they are given the opportunity to see the complete issue for themselves (by having a link to the full debate), rather than writing 10 different short and inadequate explanations for each "dialect-language" page.

- As for merging this article into Spoken Chinese, well since a lot of articles link to it specifically, it is better to set it apart as its own article. -- ran (talk) 17:17, 18 December 2005 (UTC)

- No one "should" do anything. We are not in the business of forcing people to read a certain amount of text just so they can be privvy to the fact that linguistic controversies exist. If we were doing that we wouldn't have a stated goal of keeping a summary style. Assuming that your own needs for information are equally applicable to everyone is not a good premise for writing texts that can be understood and appreciated by the widest possible audience. In fact, I'd say this is probably one of Wikipedias biggest problems right now, rather than the lack of factual accuracy. Too many people are filling articles to the brim with super-specific facts until they are that much difficult for outsiders to appreciate and then fiercly protecting it against anything that is considered "dumbing down".

- Yes, the links have existed, but linking to the wrong article. What you're suggesting is that rather than taking this up at Chinese dialects (or whatever the title should be), which is the topic at hand, we have to create a separate debate article about an issue which really isn't all that hard to summarize or even to present in a neutral fashion. In it's proper context, even.

- Peter Isotalo 13:58, 26 December 2005 (UTC)

- Habing a seperate article is in fact a good solution to the problem of articles being filled with minutiae and with the problem of articles otherwise being dumbed down. All that minutiae can be moved elsewhere so that it does not interfere with the flow of the main article, but at the same time exploring the subject as thoroughly as possible. There should of course be some sort of summary in the main article as well, but not in depth. Theshibboleth 01:08, 10 January 2006 (UTC)

- The arguments of above are wrong because for starters it has never been proved that there was only one single spoken Sino (Chinese) language at any one point in time in recorded Chinese history, which then evolved into the variety of today. Secondly, the alleged promotion of a single spoken language (for argument's sake, let's call it standard spoken Mandarin) by governments in history did not mean the suppression of the people's native spoken languages. This could be easily seen to be the case because for the vast majority of officials, their native spoken language would not have been standard spoken Mandarin. This is the case so much so that upto the current president of China, Mr Hu, none of the top leader of modern China were native speakers (meaning speaking it without a noticeable accent) of standard Mandarin (ref: Sun Yat-sen, Chiang Kai-shek, Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin and many others), and none of them suffered because of it. 86.180.55.126 (talk) 00:07, 25 October 2010 (UTC)

Comparison with Arabic

Perhaps another good example would be a comparison with Arabic? Like Chinese, Arabic has split into mutually unintelligible variants, but is mostly considered a single "language", and still retains only a single written standard. And like classical Chinese, it has also been historically used even among non-Arabic peoples as a lingua franca in Islamic states.--Yuje 06:28, 12 July 2006 (UTC)

Classical chinese is NOT a spoken language like arabic, it is literary and can be written in any tongue.Forkuna Bibhead (talk) 03:38, 5 January 2009 (UTC)

- Literary Arabic in its modern form (Modern Standard Arabic) (very close but not identical to Classical Arabic, referred to by many linguist as 2 registers of the same language) can be compared to Standard Mandarin, as both are standard written forms and the language of the formal media and education, so spoken formal forms can be compared too, although the knowledge and usage of the formal Arabic is far more restricted than formal Chinese and its knowledge is not as good, also due to poor education in the Arab world and much less communication between Arab speaking countries.

- Spoken Varieties of Arabic are partially mutually intelligible and all of them have a common vocabulary layer with the standard Arabic. Some Arabic dialects may serve as a lingua franca to an extent and often more preferred than standard Arabic.

- Classical Arabic and Modern Standard Arabic, like Classical Chinese are no-one's spoken language but it's being promoted and is better understood by most Arabs. It has a long way to go before standard Arabic becomes someone's mother tongue like Standard Chinese is now. Unlike Classical Chinese, standard (or classical Arabic) is still in use but it's usage in an informal conversation is considered stilted and avoid by most Arabs. Educated speakers are much more likely to speak Literary Arabic in an interview.

- In short, there are both similarities and differences between the Chinese and Arabic diglossia, the terms classical, standard and dialects may have different meanings when referring to one or the other language. Anatoli (talk) 02:50, 2 February 2009 (UTC)

History?

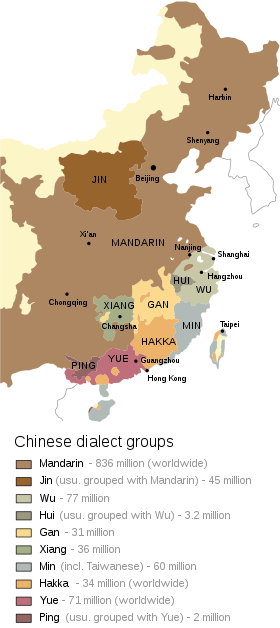

Does anyone know of the history of the varieties? Does anyone know when for example Cantonese or Min became recognised as different kinds of Chinese? Are there explanations for the pockets of varieties far from the main area like the spot of Gan spoken in the middle of the Xiang area according to the map?

I realise the map is an oversimplification and that people mix much more than is visible. Still, there may be some records on large movements of people that explain some of the pockets. Mlewan 10:54, 20 July 2006 (UTC)

Comaprison with India?

What's this about China being several separate kingdoms prior to contact with Europeans? That makes no sense, as it would either be the Ming Dynasty, or the Machus, which would be one Empire. 132.205.44.5 23:10, 11 July 2007 (UTC)

The move

I moved the article to "Varieties of Chinese" to correspond with some other articles whose titles are "Varieties of Arabic", "Varieties of French", "Varieties of Modern Greek", "Varieties of the Romanian language". ✉ Hello World! 11:07, 8 August 2008 (UTC)

Internal diversity in Chinese

In the text it says "Internal diversity in Chinese, with respect to grammar, vocabulary, and syntax, is comparable to the Romance languages, and greater than the Germanic and Slavic languages." Problem is that this doesn't add up to the Germanic Languages article where it says "Germanic languages differ from each other to a greater degree than do some other language families such as the Romance or Slavic languages." One states clearly that north Germanic languages are more diverse and the other implies that Romance language are more diverse.

Can somone look at this? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 84.209.17.70 (talk) 22:25, 1 February 2009 (UTC)

Spoken Mandarin (官话) - 1st and 2nd language

I wonder if anyone could provide and add the number of Mandarin speakers as the 2nd language. Most dialect speakers, especially in cities have a good command of Mandarin. The article mentions that Mandarin is a mandatory subject but doesn't provide figures how many people know it as a 2nd language.

Are the figures up-to-date about the first language? According to The 30 Most Spoken Languages in the World it's 1,120 mln. Anyway, also look at List of languages by number of native speakers. Anatoli (talk) 03:02, 2 February 2009 (UTC)

redundant article?

Should this article be merged with Chinese Lanaguage? Readin (talk) 16:37, 27 August 2009 (UTC)

Does language/dialect question arise in Chinese?

"Yu" and "hua" are both used for "dialects" (yueyu, guangdonghua) and for Chinese as a whole (han'yu, zhongguohua). "Fangyan" is a technical term and not used as a suffix for major dialects. So it seems to me that the question this article is preoccupied with, of whether to suffix a locality name in English with "dialect", "language", or neologisms like "regionalect" just doesn't arise much in Chinese. It seems bizarre that this isn't even mentioned. --JWB (talk) 11:54, 6 September 2009 (UTC)

- The question arises among linguists, see:

- Mair, Victor (1991). "What Is a Chinese "Dialect/Topolect"? Reflections on Some Key Sino-English Linguistic Terms". Sino-Platonic Papers. 29.

- Whether it arises among regular Chinese people is debatable I guess... rʨanaɢ (talk) 11:53, 31 March 2010 (UTC)

Please add IPA pronunciation for Romance languages

All modern Romance languages share the Latin script (though Romanians used Cyrillic for quite a while) and ultimately they all trace the way they write their words to vulgar Latin. Just by looking at the chart, an uninformed reader wouldn't be able to appreciate diversity within the group as exists today nor how the primordial sounds have shifted from Classical Latin to Vulgar Latin to modern Romance; e.g.: Italian and Spanish "sky" is written "cielo", though pronounced "chyeh-loh" in the first case, "thyeh-loh" ("th" as in "thin") in northern Spain and "syeh-loh" in southern Spain and Latin America, for the second. Quite a different sound.

Mair

Victor Mair's views are probably already well-known to most people reading this page, but in case you're interested he just made a new post on Language Log that might be helpful:

- Mair, Victor (30 March 2010). "Sinitic and Tibetic". Language Log. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

rʨanaɢ (talk) 11:53, 31 March 2010 (UTC)

Comparison with european languages: does it mean anything at all?

Obviously, the composer of the table knows nothing about Chinese. How can you ever compare the pronunciation of two words while they are not even the same word?e.g. in Pekinese we call father "爸“(ba4)while in Hokkien they call father “老爹”,which is solely difference in wording, and we northeners have no problem understanding the written form! Shall I ever compare the wording of American, British and Indian English and reach to a conclusion that they are a god-know-what "English language family"?? This is a matter of national intergrity. It matters. We are one ethnic group, we use one language. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 110.174.12.47 (talk) 11:53, 13 June 2010 (UTC)

- No one will say such a silly thing, after really looking at the table, that "you northerners" can understand southern languages, not to mention minnan. As you said, what drives you mad here is "the matter of national integrity" you long for, but it's still not necessary to ignore or even deny facts. --Symane TALK 11:06, 21 June 2010 (UTC)

- What anon (110.174.12.47) said, makes perfect sense. If the same words were used in the comparison table, then the comparison would be valid. 爹, 老爹, 爸, 爸爸, 父親/父亲 are all Chinese synonyms, understood by all Chinese, pronounced somewhat differently in different dialects but written with the same characters - that's what he or she meant. Of course, there are some words used exclusively in dialects (their basic form, not the exact pronunciation), which may or may not have their written form but they don't make a large percentage of words - the core vocabulary is shared by all Chinese. --Anatoli (talk) 05:37, 22 June 2010 (UTC)

- In any event, the fact that the lexical items of the core vocabulary are shared by most Chinese does not mean that either (a) these lexical items' semantic ranges are at all similar or (b) that their usages in compounds etc. will be readily understood by speakers of another regional language/dialect. In other words, the fact that most varieties' lexicons are mostly cognate with one another is not in and of itself reason to say that they are in any but the most academic sense the same words.

No, the table didn't say directly that they are not Chinese, but indicated that they are not a single language. And I never ever said that I counld understand the southern dialects, not the spoken form. But Chinese dialects are have mutually intellegible written form, which is not even mentioned in this table. By the way, the Jeju DIALECT of Korean language is not understood by the korean speakers living in the Korean Peninsula, either orally or in written form, but still considered a DIALECT, and no one even talks about introducinga so-called "Korean Language family". So why treat Chinese differently? 110.174.12.47 (talk) 05:41, 10 July 2010 (UTC)

- Yes, but speakers of Norwegian and Swedish can understand one another perfectly in conversation. So does that make them both mere dialects of scandanavian? Of course not. The language vs. dialect distinction is purely political. So if, for political reasons, you want to construe Chinese as a single language- there's nothing wrong with that. But don't pretend that there is any non-political objective sense in which you can make this claim.

- And I must say I am tired of being told that there is only one Chinese language because all the dialects are mutually intelligible in written form. They aren't. (Read part two of John DeFrancis' The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy for a detailed exploration of this fallacy.) Any mandarin-speaker who seriously believes this has never actually tried to read something like a simple comic-book written in Wu. In fact, I challenge you to tell me what the following specimen of written Hokkien means:

- 我家己人有淡薄无爽快看啥痟?

- If you read it as if it were mandarin and thought it meant something weird like the self of my family is weakly not feeling reinvigorated- Look what a headache?, you were wrong. It just means I'm not feeling well. What the hell are you looking at? Ugh. People's ability to delude themselves astounds me. It's fallacies like this that make linguists want to start drinking in the morning. Szfski (talk) 09:15, 1 October 2010 (UTC)

Incorrect Vocabulary in List

The words for "man" and "woman" in the Minnan list are incorrect.Lam and Li are used only in compounds and belong to literary Chinese not spoken Minnan. The correct terms are ta-po and tsa-bɔ respectively. —Preceding unsigned comment added by Darth Dumbledore (talk • contribs) 18:38, 14 June 2010 (UTC)

Chinese in Written Form (Questions and Remarks)

Please pardon the stupid question, I cannot seem to find a good answer anywhere. Do different dialects use different characters or do Chinese people use the same characters? Like, is it possible to say that a text is from a certain region based on what characters are being used, or is it solely a question of vocabulary? (Pronunciation doesn't interest me, as long as the same characters are being used.) I find it interesting that Chinese is considered as ONE language, while Serbian, Croatian and Bosnian are considered as separate languages by many people. This is of course due to political reasons, but this still seems really odd and - if I may say so - far-fetched to me. I live in Switzerland, where we speak Swiss German, which is considered a dialect of German, even though the differences are considerably bigger (than between Serbian, Croatian and Bosnian). An average German doesn't understand Swiss German (although he might be able to get the main idea of a sentence). 46.126.180.120 (talk) 14:32, 11 September 2010 (UTC) (lKj)

- You ask a good question. What people (including linguists) neglect is that as well as spoken dialects/languages within the Sino languages family, for the purpose of education and official communication there is one dialect of written Chinese, which in English was/ is called Mandarin. This written dialect of Chinese was/is the version taught for the purpose of education for the past several millenia to all Han Chinese of whatever dialectal group. It is this dialect of written Chinese that allowed the communication in writing amongst the different Han Chinese groups. Chinese people who speak 2 or more dialects fluently have no problems in flipping between the languages even when the spoken words in these languages use different cognates. Of course if you spoke only one dialect you may find translating it into another dialect using different cognates a bit strange, as pointed out by the Hokkien example given in contribution above. 86.180.55.126 (talk) 00:29, 25 October 2010 (UTC)

merge

Spoken Chinese is better developed, and older, than this article, but it's a somewhat odd title, and it covers the same topic. Written Chinese is its own topic, since the Chinese written language has historically taken on a life of its own, but "spoken Chinese" really isn't: It's just Chinese. Merge? — kwami (talk) 12:00, 1 February 2011 (UTC)

Assessment comment

The comment(s) below were originally left at Talk:Varieties of Chinese/Comments, and are posted here for posterity. Following several discussions in past years, these subpages are now deprecated. The comments may be irrelevant or outdated; if so, please feel free to remove this section.

| No references. --Ideogram 10:27, 17 February 2007 (UTC) |

Last edited at 02:17, 2 February 2011 (UTC). Substituted at 20:57, 4 May 2016 (UTC)

| This page is an archive of past discussions. Do not edit the contents of this page. If you wish to start a new discussion or revive an old one, please do so on the current talk page. |

Standard Chinese or Mandarin?

IMO Mandarin is anachronistic - more suited to Qing officials and ducks. Can we edit the article to refer to 'standard Chinese'? After all the English speak English (not Anglo-saxon). The Italians speak Italian (not Tuscan). The Spanish speak Spanish (not Castilian), etc etc. Thanks. --Kleinzach 06:21, 8 February 2011 (UTC)

- Hmm. Let me assume good faith here. This section title (above) is entitled 'Standard Chinese or Mandarin?'. My first post contained a question. that question read "Can we edit the article to refer to 'standard Chinese'?" The rest of the short message explained the background to my suggestion. Is that clear now? --Kleinzach 02:16, 9 February 2011 (UTC)

the dialect thing- its not political

as early as 1848, this english language publication (written and published by non chinese englishmen), refers to varieties of Chinese as "dialects", and acknowledges that the "Dialect" term is used differently than what a dialect in the west would be described like. It acknowledges that chinese dialects are mutually unintelligible, but calls them dialects, and says that the "Written character" is what unites them.

Therefore, the conspiracy theory thats been flying around, claiming that the term "dialec", was falsely applied to chinese languages by the communist party to deliberately misinform people that Chinese isn't a united language, is wrong.

There is no "playing politics", or lies on the part of the Chinese government regarding dialects- I didn't know that the communist party existed in 1848 and managed to magically take control of an English printing press and publishing company to print "propaganda".ΔΥΝΓΑΝΕ (talk) 01:25, 17 May 2011 (UTC)

- It most certainly is political, just as it was political when Japanese speakers claimed that the languages in the Ryukyu islands were dialects. "We call them dialects in <insert language>" is not a valid excuse, nor are the claims of a misinformed linguist from the year 1848. Linguists, today, consider the many languages of China to be separate languages and refer to them as such. What China refers to them as is irrelevant, as they are not linguists. What Chinese linguists refer to them as in Mandarin is also irrelevant, as this is an English wikipedia article. 97.81.69.177 (talk) 11:04, 31 May 2011 (UTC)

- "dialect" means regional speech, typically mutually intelligible with each other. "Fangyan" in chinese, means "regional speech", the speech/ langauge of a specific region, regardless of mutual intelligibility. There is no equivalent word in English. "Dialect", was originally chosen by englishmen who chose that word to define Fangyan, not Chinese people. the author of that 1848 publication himself acknowledged that the "Dialects", were not mutually intelligible, but he used that word to describe them for lack of a better term. back then, hardly any chinese knew english- the westerners were the first to call chinese languages "dialects".ΔΥΝΓΑΝΕ (talk) 19:34, 31 May 2011 (UTC)

- Actually, there are German dialects that people who only speak standard German cannot understand; same with Italian dialects. Linguists sometimes likewise call Spanish and Italian "dialects" or "idioms" of Modern Vulgar Latin. Hence, fangyan as "dialect" does make sense. It only seems not to sometimes because English does not have this kind of wide variation in dialects. For English-speakers, we would have to listen to other Germanic languages to get an idea of what, say, Cantonese would sound like to somebody who only spoke Mandarin (For example, here's a sample of Norwegian: [1] ) BGManofID (talk) 03:24, 9 December 2012 (UTC)

- Are you referring to language varieties that are close enough to standard High German to be viewed as variants of it -- which would exclude Plattdeutsch, Alemannisch, English, Frisian, and Dutch -- or are you referring to all of the languages called Germanic, including also Swedish, Gothic and so forth? In this case, English speakers already have a pretty good understanding of what a wide range of languages is being considered. Your comparison Norwegian:English::Cantonese:Mandarin is an interesting one, but if it is accurate, it tends to argue against considering the Chinese languages as dialects of the German language but rather as a language group about the size and breadth of the Germanic language group.

- Incidentally, you can look at that article (the one on the Germanic languages) for some indications on how the word dialect is generally used in modern descriptive linguistics -- namely for smaller differences and nonstandard or nonwritten variants. I do appreciate your evocation of dialects in the sense of daughter languages (even thousands of years later), but I suspect that this is either an older term, or one coming from historical linguistics. It's not a bad usage, just a bit arcane for the present discussion.

- I would be very interested to know if the Chinese languages : Germanic languages comparison is a good one. 89.217.3.108 (talk) 09:35, 5 May 2014 (UTC)

- Wot common Chinese people refer to the language(s) as, yes, is irrelavant, you're right. But how Chinese linguists refers to them can't be simply dismissed as such, can it? Do we not have any linguists, may I ask? I personally think that you are removing them from the discussion-----"wot do you Chinese know? This is English wikipedia!" Please, state the facts and argue the ideas, but save the patronising.110.174.12.47 (talk) 12:42, 22 July 2011 (UTC)

- The term "dialects" in English for the Chinese languages comes from an earlier period when Chinese linguistics (and linguistics in general) was not as well understood by linguists and other observers who were communicating in English. It was exacerbated by the very interesting Chinese phenomenon of several spoken languages with one written language -- certainly quite unique and not invented by the current government of China. But the continued defence of this misleading term is partly due to ignorance on the part of everyday speakers of Chinese about the definitions of linguistic terms describing the languages they use every day (such folk notions are not restricted to Chinese speakers), together with a deliberate conflation of various languages under the general term of Chinese, which is then identified with Mandarin, on the part of the current Chinese government. So yes, while the origin is complex, the continuation is definitely political -- and it mars this article to the point where you have to read linguistics from other sources than Wikipedia to really understand what is going on. 89.217.3.108 (talk) 08:50, 5 May 2014 (UTC)

Top-level grouping is presented as misleadingly definite and discrete

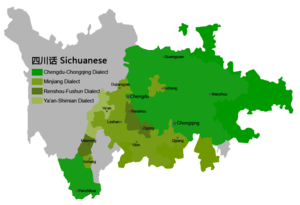

According to Gan Chinese, Gan and Xiang were only carved out of the Mandarin region in 1937. Jin Chinese was carved out in 1985 by a single linguist, Li Rong, on the basis of a single feature, retention of the final glottal stop, even though it is retained in other areas such as Southwestern Mandarin, which apparently no prominent linguist has championed promoting to a top-level group, even though Chinese people perceive Sichuanese to be as distinctive as Xiang or Gan.

Actually Sichuan, Hunan, and Jiangxi all show stratification between more Mandarinized dialects in their northern plains and more conservative, divergent dialects farther southwest in and near the hills. Here the English Wikipedia articles are behind the Chinese Wikipedia articles in incorporating newer and more detailed evidence. These patterns are actually a good fit for the wave model which is nowhere mentioned in this article, which only talks about tree structure.

Varieties_of_Chinese#Quantitative_similarity apparently remains the only actual citation (at least in English Wikipedia) of quantitative study of distance between major Chinese dialects, as opposed to particular linguists' edicts on top-level grouping presented without supporting reasoning. Apparently the presentation of a single definite tree in this article follows the standard English-language survey textbooks like Norman and Ramsey, which are now about 25 years old, and based on Chinese sources older than that.

Various linguists' positions on top-level grouping are indeed facts we should document, but Wikipedia should not strongly endorse or reify one particular position, e.g. by providing a very prominent map, tree, or outline for one grouping, and little to nothing for others, when the situation is so indefinite. Contrast Afroasiatic_languages#Distribution_and_branches which instead prominently presents the variation and conflict between linguists' views on top-level grouping of Afroasiatic. --JWB (talk) 07:01, 10 July 2011 (UTC)

I'm rereading Norman, and he does talk about the wave model; his primary division of Chinese dialects is into Northern, Southern, and a transitional Central zone, which includes Wu, and has received multiple waves of Northern influence. Interestingly his discussion (Chapter 8) is based on 12 cities as major data points, including Kunming, but none in Sichuan. The Yunnan dialect area originated with a Northern Chinese population colonizing a previously non-Chinese-speaking areas, bypassing influence from southern Chinese dialects, and Kunming is still noted for its intelligibility with Beijing. On the other hand, Sichuan has more conservative, less Mandarinized dialects in southwestern Sichuan. Norman has almost no mention of Sichuan; it appears only once in the index. Taking this into account, the situation in Sichuan looks similar to those in Hunan and Jiangxi, but has been glossed over in favor of a contiguous Southwestern Mandarin area because of the obscurity of southwestern Sichuan. --JWB (talk) 23:20, 11 July 2011 (UTC)

Here is machine translation of a table from zh:官话#.E5.88.86.E5.8C.BA.E5.8F.B2:

Partitioning method for a variety of Mandarin, the following is a brief history of the partition:

| Years | Partitioning | Note |

| 1934 | North Mandarin , Hua Nanguan if two independent large dialect | "Mandarin" is the first time for Chinese district; contains the current language Jin , Xiang language , Gan |

| 1937 - 1948 | Northern Mandarin , Mandarin on the river (ie, Southwest Mandarin ), Xiajiang Mandarin (the JAC Mandarin ) for the three separate major dialect | Hunan and Jiangxi language area is set aside, the scope and Mandarin area has been and now Mandarin and Shanxi very close to the range of language areas. |

| 1955 - 1981 | Mandarin was first merged into a large dialect area. Internal partitions in different ways, a more popular way will be divided into North Mandarin , Northwest Mandarin , Mandarin JAC and the Southwest Mandarin | Mandarin Chinese has since become a major dialect |

| 1987 Atlas of Chinese language | Mandarin dialect for a large area, the internal into the Northeast Mandarin , Beijing Mandarin , Jiao-Liao Mandarin , Ji Luguan words , Zhongyuan Mandarin , Lan silver Mandarin , Mandarin JAC and the Southwest Mandarin | Jin Mandarin language was first set aside; 8 Zone to become the most popular Chinese dialect classification of academic |

--JWB (talk) 23:50, 12 July 2011 (UTC)

"Examples of variations"---is it really valid?

FIrst of all, I am not a linguist, but I am Chinese and I received education in China up to year 9, so I assume that it is appropriate for me to state some of my views. I don't think the comparison offered in this section is the most valid one. The "cognate to cognate" translation from Hokkien to Mandarin, in a way, isn't really a valid translation, and I personally think that the translator has the purpose of creating an awkward sentence in mind when doing the translation. If "我家己人"("I myself" in Hokkien) can be translated as "My family's own person", then "我自己个儿“("I myself" in Beijing Mandarin) may as well mean "myself-single-son"! As you can see, a sentence in Mandarin can also be subject to such manipulation and become unrecognisable. It is clear that any such word to word interpretation should not be valid. A passage written fully in British slang would produce some comic effect when interpreted with the algorithm for Standard English. Also, "我家己人 有淡薄 无爽快“isn't really meaningless to a Mandarin speaker. "我家己人” clearly contains elements of "I"(我) and "self"(己人) in it, while the meaning of “淡薄”(weak;slight) can be easily extended to serve as a qualification for the degree of something. "无" is also commonly used in Mandarin to indicate negativity, and “爽快” does not merely mean mentally "refreshed"; it can mean physically refreshed, i.e. free of desease. In this way the meaning can be easily formed.110.174.12.47 (talk) 13:15, 22 July 2011 (UTC)

- I agree with this statement as a Southern Chinese who also speaks Mandarin. I can tell you that 家己人 means exactly the same thing as 自己 in putonghua but that the way they pronounce things in Hokkien makes use of the 家 in this case just like Wu would say 自家 to mean the same thing as 自己. In the same way 淡薄 is only an archaic way of saying something is in a slight degree which in putonghua is 一点. 无 is a synonym of 不. So the two phrases

- "我家己人 有淡薄 无爽快" and

- "我自己有一点不舒服" can be paired like this. 我家己人/我自己 有淡薄/有一点 无/不 爽快/舒服.

- So for any Chinese person to read this it might look awkward at first but you'll be able to figure it out in no time. I'll add the Wu to extend the point. 我家己人/我自己/我自家 有淡薄/有一点/有些 无/不/勿 爽快/舒服/舍意.

- This is not to say there isn't something nonsensical to Mandarin in Hokkien but that this wasn't it. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 207.38.213.212 (talk) 20:15, 6 July 2012 (UTC)

Chinese switch on zh wiki

Sorry if this is the wrong place to ask this question, but what's the switch called on the Chinese wiki that allows you to view different variants of Chinese? 188.29.118.236 (talk) 14:57, 16 February 2013 (UTC)

- If you mean different regional dialects, they appear as separate languages here on Wikipedia, so check under the tab "其他语言" in the left. There's one for Mandarin, Cantonese and Hakka. On the Mandarin page, you switch between traditional and simplified scripts by clicking on the button on the upper left next to "Article" and "Talk".202.171.163.7 (talk) 11:26, 10 August 2013 (UTC)

Political and cultural-centric POV - CHANGE TITLE

I move that this article be retitled either: "Chinese Dialects", or "Chinese Languages", both phrases actually meaning the same thing. I prefer the latter as it does no carry the implication either of any subordinate status or of any superordinate reality ie it does not align with a nationalist/political framework but with a linguistic one. The phrase "Varieties of Chinese" I find derogatory. It is simply a political POV and therefroe not something that Wiki should tolerate. There is no hard difference between dialects and languages as many article on wiki testify, and "Chinese" is no exception to this fact. LookingGlass (talk) 10:29, 22 February 2013 (UTC)

- It's actually the opposite: the current title is neural, and the two you suggest are not. And BTW, they do not mean the same thing, but opposite things. — kwami (talk) 04:44, 23 February 2013 (UTC)

- Please would you provide some substance to your opinion Kwamikagami? Why do you think that "Chinese languages" is not neutral but "Varieties of Chinese" is? To me "Varieties of Chinese" sounds colonialistic. "Varieties" are variations on a dominant theme. However in some case these langauges/dialects are quite distict things. In any even the term "varieties" is not one that is recognised as far as I am aware in linguistics. LookingGlass (talk) 12:54, 25 February 2013 (UTC)

- Kwami is correct. See Variety (linguistics). Keahapana (talk) 23:34, 25 February 2013 (UTC)

Thank you for the reference Keahapana. However there remains a problem in my opinion. Wikipedia is a general purpose encyclopedia, not a specialist one. Especially the titles of articles should therefore use everyday English rather than technical jargon, especially where such jargon is unreferenced outside of the specialist area concerned. Here, for instance, neither Merriam Webster online nor Collins Dictionary and Thesaurus list the meaning "lect" for the word: "variety", so while the term may be technically correct in linguistic circles (contrary to my initial understanding), it is obfuscatory and misleading as nobody outside of that sphere has access to the knowledge of its usse by the discipline (and in a title it cannot be cross-referenced) Using the techincal term seems seems to serves no purpose than the promotion of a POV. This point is seen in the section on classification where it is stated "The difference between Mandarin and other Chinese "dialects" is easily comparable to that between English and its Germanic cousin languages (German, Norwegian, Dutch, Swedish, etc.)". Again, in a non-technical article, it would be absurd to suggest that English, German, Norwegian, Dutch, Swedish, etc. were "varieties" of a macro language. I notice now that the article seems to be based almost entirely upon a 19C work by Samuel Wells Williams, an active US missionary and diplomat. The title seems to me neither to further the development of a non-POV article (ie one that separates it from or makes clear its political and cultural aspect) nor to assist the general reader in quickly understanding the subject of the article. The whole promotes a the political aspect of language classification. LookingGlass (talk) 19:46, 5 March 2013 (UTC)

- I agree that it is politically motivated. "Varieties" is not wrong, if you read the Wikipedia article on the term, but it is imprecise because it equivocates between language and dialect. "Languages" is the more commonly understandable term, and it is more precise because it makes it clear that we are really talking about a language group. People are sticking to "varieties" because "languages" offends some people's world view. But it should not; Chinese is a language family like any other, it should be describable using normal linguistic terms without people getting bothered about it.

- Incidentally the discussion does draw our attention to one feature of modern linguistics that sometimes troubles me: modern linguistics gives primacy to spoken language as the "real" language. But that is a whole other discussion. 89.217.3.108 (talk) 09:56, 5 May 2014 (UTC)

I basically agree with LookingGlass. Some people say it is "neutral" to use this title. But the purpose of such a "neutral" term is to satisfy some people's political view of language diversity. Just one simple question: do we use "varieties of Romance" for the article on the Romance languages? NO, even though, as pointed out in the first sentence of the Classification section, the Romance languages are actually less varied than the Han (Chinese) languages. I'm sure there are also some people out there that think the Romance languages are somewhat dialects of a macro language because of the level of mutual intelligibility. Why do we have to use "varieties" in the title only for the Han languages? Is the political view of some people really so important that we need, in a linguistic article, to conceal the fact that they are languages, not dialects? Lysimachi (talk) 00:32, 21 December 2014 (UTC)

- Varieties seems to be used quite often in the scholarly literature. It covers both languages and dialects, as this article does. Having two articles called Chinese language and Chinese languages would be a bit confusing, and merging the two would probably result in an article that was too big (though it's a possibility). W. P. Uzer (talk) 10:55, 21 December 2014 (UTC)

- In fact, the two probably should be merged. They are dealing with the same topic, and we shouldn't really be having two articles on the same topic just on the grounds that there are different points of view as to whether it's a single language or not. There are anyway separate articles on Written Chinese and Standard Chinese. I would call the merged article Chinese languages - I think the idea that they are separate languages is well enough known and accepted at least sufficiently as not to surprise anyone. W. P. Uzer (talk) 21:27, 23 December 2014 (UTC)

- The Chinese language article covers a broader topic, roughly matching the whole of the Cambridge Language Surveys Chinese volume, in which chapters or pairs of chapters correspond to sub-articles here:

- In fact, the two probably should be merged. They are dealing with the same topic, and we shouldn't really be having two articles on the same topic just on the grounds that there are different points of view as to whether it's a single language or not. There are anyway separate articles on Written Chinese and Standard Chinese. I would call the merged article Chinese languages - I think the idea that they are separate languages is well enough known and accepted at least sufficiently as not to surprise anyone. W. P. Uzer (talk) 21:27, 23 December 2014 (UTC)

Chapter Wiki article(s) 1. Introduction 2. The historical phonology of Chinese Historical Chinese phonology 3. The Chinese script Chinese characters, Written Chinese 4. The classical and literary languages Classical Chinese 5. The rise development of the written vernacular Written vernacular Chinese 6. The modern standard language I Standard Chinese 7. The modern standard language II 8. Dialectal variation in North and Central China Varieties of Chinese, Sinitic languages 9. The dialects of the Southeast 10. Language and society bits in several articles

- There are a couple of forks here, but the overall article isn't one of them. Kanguole 01:29, 24 December 2014 (UTC)

- So would you say that this article and Sinitic languages is an unnecessary fork? W. P. Uzer (talk) 07:47, 24 December 2014 (UTC)

- Probably, though Sinitic languages is an incomplete list without content or context. Also, the groups it calls "languages" are themselves composed of multiple non-mutually-intelligible varieties. Kanguole 11:32, 24 December 2014 (UTC)

- So would you say that this article and Sinitic languages is an unnecessary fork? W. P. Uzer (talk) 07:47, 24 December 2014 (UTC)

- There are a couple of forks here, but the overall article isn't one of them. Kanguole 01:29, 24 December 2014 (UTC)

??

"In addition, while speaking similar dialect provides very strong group identity at the level of a city or county, the high degree of linguistic diversity limits the amount of group solidarity at larger levels. Finally, the linguistic diversity of southern China makes it likely that in any large group of Chinese, Mandarin will be the only form of speech that everyone understands." I don't really understand this segment at all. This belongs to the "Political issues" section. First, it says "while speaking similar dialect provides very strong group identity at the level of a city or county." I interpret that as speaking similar dialect is a good thing then the next clause is about linguistic diversity is bad. While something is good, something else is bad. I have no idea why the 2 totally different ideas are connected with a comma in the same sentence? Plus the "while" conjunction is not even being used correctly. The sentence simply doesn't make any sense. Second, "Finally, the linguistic diversity of southern China makes it likely that in any large group of Chinese, Mandarin will be the only form of speech that everyone understands," how is that a political issue? The second sentence shows the benefits of knowing Mandarin (I believe the Mandarin in this context means the same as "Standard Chinese" language) so why is it in the "Political issues" section? Come on, Wikipedia is only this good??75.168.140.124 (talk) 08:12, 7 December 2013 (UTC)

citation needed

I highlight a part of a sentence in the intro that needs a reliable citation. It goes "Because they share a common written form,[1] most Chinese speakers and Chinese linguists perceive them to be variations of a single Chinese language". Can anyone, especially the one who wrote this sentence, show us a study that surveyed a significant number of "Chinese speakers" and a significant number of "Chinese linguists", of which more than half say they perceive "the varieties of Chinese" to be "variations of a single Chinese language" because "they share a common written form"? If there is no such study, I don't think such statement should be there. Wikipedia is based on reliable sources, not personal views.Lysimachi (talk) 17:23, 18 December 2014 (UTC)

- I changed this sentence and gave sources for what I wrote in its place. W. P. Uzer (talk) 21:29, 23 December 2014 (UTC)

- Thanks for adding the reference, W. P. Uzer. However, there still seems to be two problems.

- First, in the book, it was not indicated at all why the varieties of Chinese (Han languages) are popularly perceived as a single language, but in the present version of the article, the reasons are given. What is the reference that the reasons are the "common written form" and "that they are spoken chiefly within a single politically unified country"? I'm especially curious how you came to the "common written form" being the reason. Would Germans and Italians think German and Italian are the same language because they both use the Latin script? OK, some people may say the Han characters are written the same for different varieties of Chinese, but the words are spelled differently for different European languages. However, the different Han languages also use different characters and some characters are used in some but rarely in others (e.g., English: They are eating a baozi right now.; Mandarin:現在他們在吃包子; Yue: 佢哋而家食緊包). Also it is more common for some Han languages to use Latin script (please take a look at the 客家語/Hak-kâ-ngî version of the article), because there are many spoken syllables without unambiguous written characters that correspond.

- Second, per WP:V, the cited sources should be reliable, preferably those with "fact-checking and accuracy" or "academic and peer-reviewed publications". Is the book you cited a peer-reviewed one? The part of the book cited does not include any reference to support the notion that the Han languages popularly perceived to be variants of the same language, nor did it do any study to support that. In this regard, that notion seems merely to be the author's own perception. In addition, in the same sentence where the "popular perception" is mentioned, the author also said that "There is as yet no agreed Romanisation system for other [i.e., non-Mandarin] spoken varieties of Chinese ... it seems unlikely that efforts will be made to design such systems". For this book published in 1994, both of those suggestions seem to be wrong, as there had already been effort to design such systems (e.g. Church Romanization for Southern Min or Cantonese Pinyin for Yue). Also, the author seemed to suggest that there is an agreed system for Mandarin romanization, but it was not true because, at least at that time, the Taiwanese used system(s) other than Pinyin for Mandarin. Such ignorance of Han languages makes me concerned about the reliability of this book. — Preceding unsigned comment added by Lysimachi (talk • contribs) 00:31, 24 December 2014 (UTC)

- Certainly this needs some more work, preferably with some expansion in the rest of the article. Others may know of better and more detailed sources about this matter. However, I can find plenty of sources that express similar sentiments to the two books I cited, it's not just the view of that one author. W. P. Uzer (talk) 10:04, 24 December 2014 (UTC)

- If it is personal view or "sentiments", it should be pointed out in the article it is the view of a particular author who thinks it is "popularly perceived" that way (per WP:POV). Also please note, as mentioned above, not all Han languages use the same written form. It is therefore misleading to say "because the varieties share a common written form". Lysimachi (talk) 00:16, 6 January 2015 (UTC)

- Certainly this needs some more work, preferably with some expansion in the rest of the article. Others may know of better and more detailed sources about this matter. However, I can find plenty of sources that express similar sentiments to the two books I cited, it's not just the view of that one author. W. P. Uzer (talk) 10:04, 24 December 2014 (UTC)

This question seems to have re-arisen. Is it really not possible to find a source for the statement that "Chinese linguists often consider them to all be dialects of a single language"? And if not, then perhaps it's time for Wikipedia itself to abandon its apparent position that there is one single Chinese language (as reflected in the title of the main article, Chinese language, and various statements that imply that it is only certain linguists who consider Chinese to be more than one language)? W. P. Uzer (talk) 06:44, 24 April 2015 (UTC)

- People who want a particular statement to be in article text should indeed come forward with a source. What source is that? -- WeijiBaikeBianji (talk, how I edit) 04:15, 20 July 2015 (UTC)

Sinitic languages, Varieties of Chinese, Chinese languages, Spoken Chinese, and other titles

The good work that other editors have put into this article has included a merger of this article with a former article titled Spoken Chinese language. I see that this article, as displayed to a user who looks it up directly by its current title, Varieties of Chinese, includes a redirect notice at the top of the page saying "Chinese languages" redirects here. For other languages spoken in China, see Languages of China." I also see that our encyclopedia includes an article Sinitic languages. As a speaker of Chinese/Sinitic languages, it occurs to me that I should discuss with all of you a treatment of this article's topic that is consistent with the published reliable sources and consistent with the Wikipedia neutral point of view policy. I have been speaking one variety of Chinese since 1975, and at least two since 1976. I am conversant in (I'll omit wikilinks here, although we should consult the relevant articles as needed) the speech variety commonplace in Beijing (and first learned it from a native of Beijing) often known to English speakers as "Mandarin" and to linguists both inside and outside China as "Modern Standard Chinese" (現代標準漢語), which of course has several variant names in everyday speech in Chinese. I have worked for many years as an interpreter of that language into and out of English. I can also converse in (in descending order of proficiency) the Minnan speech of Taiwan ("Taiwanese"), the Yue speech of Hong Kong ("Cantonese") and the Hakka speech of Taiwan ("Hakka"). I took a formal graduate-level course in Chinese dialectology the first time I lived in Taiwan. I would like to initiate discussion here among the various editors who have devoted so much work to improvement of this article and related articles about how to link the subtopics included in Sinitic languages with the subtopics included here (by merger?) and how to discuss the points of view expressed by the use of titles as disparate as Sinitic languages and Spoken Chinese language for articles on many of the same real-world phenomena. Below I will list some sources to get this discussion started, and of course I welcome suggestions of reliable sources from other editors who join the discussion. Various articles from the Encyclopedia of language & linguistics are one way to start a search for sources, as most of the articles cite other publications.

Blake, B.J. (2006). "Classification of Languages". In Brown, Keith (ed.). Encyclopedia of language & linguistics. Elsevier. pp. 446–457. doi:10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/05162-2. ISBN 978-0-08-044299-0. Retrieved 20 July 2015. The Sino-Tibetan languages include the Sinitic family and Tibeto-Burman. Sinitic can be equated with Chinese, but Chinese is popularly understood to be a single language, whereas in fact it is more like a family of languages, one of which, Mandarin Chinese, is the standard, based largely on the Beijing dialect.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid |ref=harv (help); Unknown parameter |laydate= ignored (help); Unknown parameter |laysummary= ignored (help) – via ScienceDirect (Subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries.)

Bradley, D. (2006). "China: Language Situation". In Brown, Keith (ed.). Encyclopedia of language & linguistics. Elsevier. pp. 319–323. doi:10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/01685-0. ISBN 978-0-08-044299-0. Retrieved 20 July 2015. Outsider linguists often say that the Han Chinese speak seven distinct, mutually unintelligible languages ... Fangyan is usually translated as 'dialect' and yuyan as 'language', but their meanings are broader.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid |ref=harv (help); Unknown parameter |laydate= ignored (help); Unknown parameter |laysummary= ignored (help) – via ScienceDirect (Subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries.)

DeChicchis, J. (2006). "Taiwan: Language Situation". In Brown, Keith (ed.). Encyclopedia of language & linguistics. Elsevier. pp. 482–484. doi:10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/01703-X. ISBN 978-0-08-044299-0. Retrieved 20 July 2015. An important lingua franca, Min Nan is the second most common language in terrestrial television broadcasts, and the Amoy Bible is popular among certain Christians. On the other hand, Hakka Chinese is strictly an emblematic language of the Hakka ethnic group that is used in their villages on Formosa. Many ethnic Hakka (by some estimates, about half) have lost the ability to speak Hakka, especially in urban areas, but a Hakka language revival is currently underway, and Hakka-language radio programs enjoy increasing popularity. In contrast, Mandarin Chinese (locally Guoyu or Kuoyü 國語 but also known as Huayu 华语 or Putonghua 普通话), which is historically the third Sinitic language of Taiwan, became a language of significant immigration in 1949, when the ROC made Taipei its government seat.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid |ref=harv (help); Unknown parameter |laydate= ignored (help); Unknown parameter |laysummary= ignored (help) – via ScienceDirect (Subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries.)

Goodman, K.S.; Goodman, Y.M. (2006). "Mother Tongue Education: Standard Language". In Brown, Keith (ed.). Encyclopedia of language & linguistics. Elsevier. pp. 345–348. doi:10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/00648-9. ISBN 978-0-08-044299-0. Retrieved 20 July 2015. All languages are actually families of dialects that are, more or less, mutually comprehensible. When dialects are not mutually comprehensible, they are considered separate languages. For example in Spain, Catalonia has its own language that is not a dialect of Spanish and is now the language of instruction in some communities. What the Chinese refer to as dialects are actually related languages since a speaker of Shanghai dialect cannot understand a speaker of Cantonese.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid |ref=harv (help); Unknown parameter |laydate= ignored (help); Unknown parameter |laysummary= ignored (help) – via ScienceDirect (Subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries.)

Hutton, C.M. (2006). "Nationalism and Linguistics". In Brown, Keith (ed.). Encyclopedia of language & linguistics. Elsevier. pp. 485–488. doi:10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/01363-8. ISBN 978-0-08-044299-0. Retrieved 20 July 2015. To Western linguists applying the mother tongue model of European identity politics, the Chinese regional varieties were akin to the national languages of Europe (Dyer Ball, 1907). Within the national and nationalist framework of modern Chinese linguistics, there is, however, no question but that these varieties are the dialects of a single language, Chinese. But the rise of vernacular dialect/language politics in contemporary Taiwan points to the evidently political nature of these categorizations.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid |ref=harv (help); Unknown parameter |laydate= ignored (help); Unknown parameter |laysummary= ignored (help) – via ScienceDirect (Subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries.)

LaPolla, R.J. (2006). "Sino-Tibetan Languages". In Brown, Keith (ed.). Encyclopedia of language & linguistics. Elsevier. pp. 393–396. doi:10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/02501-3. ISBN 978-0-08-044299-0. Retrieved 20 July 2015. The Sino-Tibetan (ST) language family includes the Sinitic languages (what for political reasons are known as Chinese 'dialects') and the 200 to 300 Tibeto-Burman (TB) languages.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid |ref=harv (help); Unknown parameter |laydate= ignored (help); Unknown parameter |laysummary= ignored (help) – via ScienceDirect (Subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries.)

Ross, M. (2006). "Language Families and Linguistic Diversity". In Brown, Keith (ed.). Encyclopedia of language & linguistics. Elsevier. pp. 499–507. doi:10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/01524-8. ISBN 978-0-08-044299-0. Retrieved 20 July 2015. The Sinitic network has conventionally been described as the Chinese language, comprising the Chinese dialects, but the Chinese language is comparable in diversity to the West Germanic family. This terminological situation has arisen because the Chinese language has long been coterminous with the political and social entity of China. The Chinese dialects and Chinese language are now sometimes called the Sinitic languages and the Sinitic family, leaving the term 'Chinese language' to denote the standard language.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid |ref=harv (help); Unknown parameter |laydate= ignored (help); Unknown parameter |laysummary= ignored (help) – via ScienceDirect (Subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries.)

As for the application of neutral point of view policy to this article, plainly there is a point of view represented in the literature that "Chinese" is one language and all varieties of cognate speech are "dialects" of that one language. Another point of view represented in the literature is that "Chinese" can be taken to be the designation of a branch (or two) of cognate languages, which more formally can be designated "Sinitic languages," with the current governing authorities of China, Taiwan, and Singapore agreeing on a standard modern Chinese language to be promoted in schooling and broadcasting (given a different name in each of those places, but called by linguists "現代標準漢語"). The lived experience of people living in China, as multiple sources make very clear, is that many individuals from the broad Chinese Sprachraum cannot understand one another at all if each speaks a home native language without adaptation to common speech varieties that take some other local speech variety as a standard. The writings of the late Yuen Ren Chao are very informative on several of these issues. Let's discuss. Feel free to bring more sources to bear on the discussion. Thanks for your past work on this and other articles. -- WeijiBaikeBianji (talk, how I edit) 14:27, 27 July 2015 (UTC)

- Thank you for bringing forth those sources. My own research had more-or-less run dry. In particular (to make it easy on ourselves), the thing we want to find in RS's is meta-statements, that is, claims about what linguists tend to do in regards to the dialectal variation within Chinese. Unfortunately, the quotes you've provided from EL&L aren't as helpful as we'd like because they are vague and even contradictory.

- First, we have Blake, who says that the one-language perspective is a "popular" choice (implying the lay public disagrees with linguistic conventions), and Goodman, LaPolla, and Ross seem to echo that the lay public in China take this view, though this is something implied. We similarly have to read between the lines to see what these authors say about what position linguists tend to hold. Goodman says "Chinese", which might include Chinese linguists, but we can't be sure. LaPolla uses the passive voice and therefore doesn't clarify who knows these varieties as dialects. Ross uses the term "conventionally" which could mean anything. Similarly, the Hutton quote is too vague to be of any help; they are clearly taking about past usage in applying the "mother tongue model" but who is and is not applying the national/nationalist model?

- Goodman seems to imply that linguists themselves prefer to categorize the varieties as languages on the grounds of mutual intelligibility, but I know from other sources that not only do linguists often make an exception with Chinese, but that authors have even made this very same general statement about using mutual intelligibility only to later on in the same work outline why Chinese is an exception to this general practice. Moreover, if mutual intelligibility were to be used for Chinese, there would be hundreds of languages, not just seven.

- Finally, while some of this contradicts some of the sourcing I have found (outlined at Talk:Chinese language, Bradley is self-contradictory, saying that fangyan is translated as 'dialect' but that linguists outside of China refer to the seven major dialect groupings as languages (incidentally, while I had not encountered the term yuyan before, a quick search shows that it is present in the Chinese Wikipedia's article on English and not on Cantonese). If we are to take Bradley's claim about linguistic conventions at face value, then there is a clear contradiction with Norman (2003) who is cited at Chinese language#Nomenclature.

- With the three perspectives you point to (one-language, language family, and mutually unintelligible), what sorts of changes would you like to see in this and other articles relating to Chinese? — Ƶ§œš¹ [lɛts b̥iː pʰəˈlaɪˀt] 17:14, 27 July 2015 (UTC)

- "Sinitic languages" and "Varieties of Chinese" should ideally be the same article, to my mind. The "Sinitic" term comes from Victor Mair, and he continues to be its chief proponent. It's still unsettled as to whether "the Sinitic languages" or "the Chinese languages" is preferred, as Zev Handel notes in the Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics (p. 34) from earlier this year. He chose "Sinitic" for his chapter, but there's no clear winner yet. I have no preference one way or the other at the moment, though I think "Sinitic" will probably win out eventually. White Whirlwind 咨 18:52, 27 July 2015 (UTC)

- Whatever we call them, it is useful IMO to distinguish the Chinese languages proper from broader conceptions of Sinitic including the Bai languages, Caijia, and the like -- unless we are going to advocate the view that Bai is a variety of Chinese, a POV that I suspect would fail in a review of the lit.

- Also, if we call the article "Chinese languages" (or even "Sinitic languages" but restrict it to Chinese), then readers will reasonably expect a list of these languages, just as we have for practically all other family articles. But, we can't do that, because no-one knows what the Chinese languages are, and that's not likely to change anytime soon. — kwami (talk) 20:22, 27 July 2015 (UTC)

- My impression is that there's little interest in expanded conceptions of Sinitic these days. Across Sino-Tibetan there seems to be an acknowledgement that mid-level groupings are poorly justified, and there's a need to build from the bottom up without too many prior assumptions about the higher-level structure.

- The point about "languages" titles leading readers to expect a list of languages is a good one. Everyone agrees that geographically separated varieties are mutually unintelligible, and there is considerable interest in classifying the varieties, but little in identifying discrete "languages". Kanguole 20:55, 27 July 2015 (UTC)

- Yes, and while the varieties of Chengdu and Beijing are MI, several varieties of SW Mandarin are not MI with Chengdu. Having Mandarin and then listing branches of Mandarin does not correspond to listing the member languages of other families, which are largely based on MI.

- As for expanded Sinitic, we do have sourced info, even if people aren't doing much with it these days. If we want to use that name, I don't know if we'd want to move the current content, or merge it to a section on broader classification. — kwami (talk) 21:43, 27 July 2015 (UTC)

- I'm no expert of Sino-Tibetan languages, but reading this discussion I found that the information contained in it is extremely interesting and it should somehow be put in the article if it's not already there. Especially the problem of listing languages: if you clearly state in the article that a list is not (directly possible), people who expect it will be happy to be told that's not possible, more than not discussing the problem at all. I also think the point of the NPOV is to inform of each and every opinion on the subject, so I don't see any immediate problem in stating what the sources given above state. Or at least the proposed grouping should be backed up with a proper source, independently of the fact that that specific grouping is widely shared or not. --SynConlanger (talk) 12:24, 18 August 2015 (UTC)

I have reverted some recent changes to the lead. The practice of describing the dialect groups as discrete languages has been explicitly criticized by Norman (2003), p. 72, so we should not present it baldly as the consensus view. (BTW, Handel said "at least a dozen distinct languages and perhaps more than twenty", not between 12 and 20.) The changes also delete text that summarized the article body. Kanguole 10:08, 16 October 2015 (UTC)

- @Kanguole: Fine, but that revert also brings back your preexisting problems of poor prose and structuring, as well as some Manual of Style issues, such as the link in the "boldface reiteration of the title", which is also missing (see WP:LINKSTYLE). I'll try again. White Whirlwind 咨 20:17, 16 October 2015 (UTC)

Varieties commonly taught in formal courses

Regarding this revert, there was indeed a source, but it was a newspaper article from 2001 saying that UHawaii had a Hokkien course and Harvard was introducing one, wich hardly justifies "commonly taught". Moreover, it seems that Harvard and Hawaii no longer offer Hokkien (or Cantonese). Regarding Cantonese, my impression is that there's been a reduction in courses, particularly in the US, but it still seems to be offered in enough places to justify retaining the statement cited to Norman (1988). Kanguole 18:25, 27 March 2016 (UTC)

- There are courses offered in Taiwan, for sure. And the same Minnan Sinitic language was spoken by more people in Singapore than Mandarin just a generation ago, and the United States Foreign Service had a course for acquiring that language. But I suppose "commonly taught" is the definitional problem here, so I'll let the latest edit stand. -- WeijiBaikeBianji (Watch my talk, How I edit) 22:01, 27 March 2016 (UTC)

- @WeijiBaikeBianji: I believe you, but do you have a source that mentions this? I did a bit of searching for "United States Foreign Service" "hokkien" and found no evidence it ever existed.--Prisencolin (talk) 01:25, 22 July 2016 (UTC)

- Hokkien or Minnan is or has been taught at Hawaii, Harvard, Stanford, SOAS University of London, Chiang Kai-shek College, UC Berkeley, and apparently several schools in France and Japan. I think this is enough to say it is commonly taught at universities.--Prisencolin (talk) 03:59, 30 August 2016 (UTC)

IPA correction

The "Vocabulary" section lists several Mandarin words with χ, the voiceless uvular fricative. As far as I know, Mandarin phonology does not include χ, even as an allophone of x, the voiceless velar fricative. Unless someone has a citation showing that the words in question are in fact pronounced with χ, I am going to change them all to x. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 174.30.27.84 (talk) 23:27, 9 May 2016 (UTC)

Requested move 1 June 2016

- The following is a closed discussion of a requested move. Please do not modify it. Subsequent comments should be made in a new section on the talk page. Editors desiring to contest the closing decision should consider a move review. No further edits should be made to this section.

The result of the move request was: Not moved as consensus to keep the article at it's current name has been established. (non-admin closure) — Music1201 talk 21:58, 6 June 2016 (UTC)

Varieties of Chinese → Dialects of Chinese – the term "dialects" is the WP:COMMONNAME, and more WP:RECOGNIZABLE than the current title. Although it is POV, the term is used by many linguists in regards to Chinese as well as the vast majority of the general public. In contrast, "varieties" is exclusively used by linguists and experts and is virtually non-existent elsewhere. Web searches for books and news seems to support the prevalence of "dialects" or "varieties". Per WP:NPOVNAME: "When the subject of an article is referred to mainly by a single common name, as evidenced through usage in a significant majority of English-language reliable sources, Wikipedia generally follows the sources and uses that name as its article title (subject to the other naming criteria)." Prisencolin (talk) 03:45, 1 June 2016 (UTC)

- Oppose on the grounds that the Chinese "dialects" are not mutually intelligible, they differ to such a degree that each of the 10 major groupings could be classified as languages on their own right. In China today they are classified as "dialects" for political reasons, the term "varieties" doesn't carry any political weight to it, and thus seems to be more neutral for this topic. — Abrahamic Faiths (talk) 16:29, 1 June 2016 (UTC)

- Strong oppose (edit conflict) This is a predominantly linguistic article. So yes, using the term most used by linguists is probably the way to go as opposed to the imprecise or POV usage of non-linguistic sources. I recommend you look at WP:NAMINGCRITERIA since following that I find the current title vastly preferable. Dialects of Chinese redirects here so the recognizable and naturalness argument doesn't really hold water since people looking for that title will get here regardless. This title is arguably more precise because delineating dialect, accent, and language is almost impossible and some of these might not be dialects but their own languages or maybe not. That's still being argued and so "varieties" seems like the way to go. Further, the issue of "language" vs "dialect" and the connotations of "dialect" and the nationalist implications of "language" are so contentious that we shouldn't be taking any side in this which is why "varieties" is used in the first place. Notice that WP:NPOVNAME says "generally", not "always" so this is likely one of those exceptions. It further says the common name should be rejected in the case of "Colloquialisms where far more encyclopedic alternatives are obvious". Dialect is being used colloquially here, not linguistically, and the more encyclopedic term would be varieties. Finally, this title is consistent with other similar articles on large (linguistically and geographically) language families. See:

- So I really don't see this move as being a good one. Wugapodes [thɔk] [kantʃɻɪbz] 16:45, 1 June 2016 (UTC)

- From what I've seen "dialects" seems to be used by linguistists instead of variety to describe Sinitic/Chinese. I am well aware of the diversity within the Chinese group, but do note that Wikipedia is not a WP:SOAPBOX for promoting certain types of terminology not in prevalent usage, so that's why I think it's important to use the WP:COMMONNAME in this instance. The current title appears to be WP:UNDUEWEIGHT.--Prisencolin (talk) 20:13, 1 June 2016 (UTC)

- The term variety is prevalent in linguistic literature. Even if it isn't as common in Chinese linguistics as dialect or language, choosing one or the other would be taking a side on an issue we have no business taking a side on. In a context like Chinese linguistics, where dialect and language are both in high enough usage, variety would be the neutral term, even if it is not used as often in the relevant literature. — Ƶ§œš¹ [lɛts b̥iː pʰəˈlaɪˀt] 20:38, 1 June 2016 (UTC)