Talk:William Nugent

| This article is rated C-class on Wikipedia's content assessment scale. It is of interest to the following WikiProjects: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A fact from William Nugent appeared on Wikipedia's Main Page in the Did you know column on 14 December 2009 (check views). The text of the entry was as follows:

|

Moved from page[edit]

Numerous references in Nugent's life history also echo plot points in the Plays, like this from the aforementioned court case:

- "The sheriff dismissed the prisoner for certain money, and (as it was informed to the Lord Deputy) for the use, or rather the abuse, of his sister."[1]

When the Lord Deputy was trying to catch William in 1584 he reported back to London:

- "He has shaven his head and otherwise disguised himself as a friar but he has laboured in vain ... I hope to obtain his head."[2]

This seems similar to the Duke, Isabella and Claudio in Measure for Measure This account of his marriage reads a lot like Romeo and Juliet and the beginning of Othello:

- ".. whereupon there fell great discord between both houses of Delvin [Nugent] and Dunsany [Plunkett]. And the maid, being by her mother and father-in-law [stepfather] brought into this city as the safest place to keep her, on Friday last at night (being the fourth of this month) the Baron of Delvin's brother being accompanied with a number of armed men, entered one of the postern gates of this city about twelve of the clock in the night (the watch being either negligent or corrupted) and with twenty naked swords entered by sleight into the house where the maid lay and forcibly carried her away, to the great terror of the mother and all the rest."[3]

But more than anything else he was known for his great literary talents, as described by Father John Lynch, one of the most important Irish historians of the period:

- "Then he learnt the more difficult niceties of the Italian language and carried his proficiency to that point that he could write Italian poetry with elegance. Before that however he had been very successful in writing poetry in Latin, English and Irish and would yield to none in the precision and excellence of his verses in each of these languages. His poems which speak for themselves are still extant."[4]

Nugent lived for a long time in England as a student at Oxford and earlier as a ward of the third Earl of Sussex,[5] the same well-known English nobleman who was the uncle of the Earl of Southampton and the founder of the Lord Chamberlain's Men players.[6] As early as 1577 he was known as a composer of 'divers sonnets' in English, to quote his friend Richard Stanihurst writing in Chapter 7 of Holinshed's Chronicles.[7]

Irishisms in Shakespeare[edit]

Hickey also drew on the many works that have been published which highlight the remarkable Irishisms in Shakespeare, like this for example by W H Blume writing in the Weekly Irish Times on the 29th of June 1901:

- "In the 'Winter's Tale' (Act 3 Sc 3), occurs a very common Hibernicism when the old shepherd exclaims, on picking up the abandoned Perdita, "A boy or a child, I wonder?"

- Exclamatory words and phrases racy of the Island of Saints are not infrequent in the plays. In "As You Like It" (Act V Sc 1) we find a popular Irish interjection in, "Faith, the priest was good enough, for all the old gentleman's saying;" and in "The Twelfth Night" (Act 1 Sc 3) Sir Andrew Aguecheek boasts, "Faith, I can cut a caper."

- "Heaven keep your honour," which occurs in 'Measure for Measure' Act II Sc 2, is a prayer which may be earned any day by a dole of a copper to an Irish beggar, and Ophelia's, "how does your honour for this many a day," is an idiomatic expression which has taken root in the "ould sod." The same may be said of "saving your honour's reverence," an apologetic tag used by the loquacious clown in "Measure for Measure," Act II Sc 1. Indeed, we doubt whether any such expressions as these last three be heard at all nowadays outside Ireland.

- "Cead mile failte", the common Irish greeting, translates to "A hundred thousand welcomes", the greeting Menenius Agrippa makes to Coriolanus.

- In 'A Midsummer's Night Dream' Act 1 scene 2, when Bottom eloquently pleads for permission to play the lion he says, "Such roaring would hang us, every mother's son." According to Hickey, the expression "every mother's son" is "seldom used at the present day by anyone but a Patlander."

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries many Irish journals and writers commented on this but they usually did not go so far as to claim that Shakespeare was therefore Irish. They always worked on the understanding that the English language had branched off sometime in the late 17th or 18th centuries with Hiberno-English preserving the older Elizabethan English language. However, some continuities existed between forms of English imported before the reign of James I and those that developed from later English implantations. Distinctive Irish pronunciations were already identified.[8] As a further example of these journal articles there is this note from the Ulster Journal of Archaeology:

- "In Routledge's lately published and very neat edition of Shakespeare's Two Gentlemen of Verona, the following note occurs on Act 4, Scene I:

- "Come, go with us, we'll bring thee to our crews.

- Mr. Collier's corrector reads 'cave,' Mr.Singer: 'caves.' I have not ventured to alter the text; but can hardly believe crews to be what the poet wrote."

- Now in Ulster the people call a pig-stye a pigcrew. Hence I am disposed to think that the poet used the word "crew" as meaning a hut or hovel, such as an outlaw would make for his abode in a forest. In all the Irish dictionaries the word cró is given as "a hut, hovel," &c.

- Another word occurring in Shakspeare in an obsolete sense, "cling," meaning to "shrink," is applied in Ulster by carpenters to the shrinking of timber."[9]

Another example from the same journal:

- "Mr. Knight, in his Pictorial Shakspeare, at the following passage in Coriolanus, [Act 3,Scene 1]

- "Siculus: This is clean kam.

- Brutus: Merely awry. When he did love his country

- It honoured him;"

- has a note in which he says: "We take this to mean 'nothing to the purpose.'"

- He is evidently ignorant of the real meaning of the word, although the expression "awry," used by Brutus, might have led him to it. There is no difficulty in explaining it, if we recollect that in Irish the word cam signifies "crooked."

- But the real difficulty seems to me to be why Shakespeare, an English writer, should be found employing pure Irish words."[10]

Irish language in Shakespeare[edit]

There is much Irish-language influence in Shakespeare's works. Elizabeth Hickey, and some other writers, touched upon this when they claimed that Shakespeare was from Ireland.[11] Further examples include: the word 'brogue', which Shakespeare uses exactly as Irish speakers do (Cymbeline Act IV scene 2 line 269); and 'puck', the spirit in A Midsummer Night's Dream, sounds a lot like Púca, the Irish for ghost; and also the phrase 'Calin o custure me' (Henry V Act IV scene 4 line 4) clearly refers to the old Irish harp melody 'Cailín ó cois Stúir mé'.[12] These examples have intrigued Irish scholars over the years and in the opinion of Elizabeth Hickey and some others further raised the prospect that Shakespeare himself was Irish.

Attainder[edit]

According to Hickey, another Shakespearean link is Nugent's attainder shortly after his rebellion in 1581. This was never reversed although he repeatedly begged the authorities to do so.[14] An Attainder was an Act of Parliament, usually passed for high treason and preceding execution, which was often characterised as a 'blood stain', 'blot' or 'corruption of blood', because it had the effect of stripping the victim's hereditary rights as well as property. An example of a 'blot' reference is found in Henry VI:

- "Was not thy father, Richard Earl of Cambridge,

- For treason executed in our late king's days?

- And, by his treason, stand'st not thou attainted,

- Corrupted, and exempt from ancient gentry?

- His trespass yet lives guilty in thy blood;

- And, till thou be restored, thou art a yeoman...

- This blot, that they object against your house,

- Shall be wiped out in the next parliament."

- (Henry VI pt 1 Act II Scene IV 90–95, 116–117.)

Ben Jonson, an acquaintance of Shakespeare, has this 'blot' reference in Timber (1640):

- "I remember, the Players have often mentioned it as an honour to Shake-speare, that in his writing, (whatsoever he penn'd) hee never blotted out line. My answer hath beene, would he had blotted a thousand. Which they thought a malevolent speech. I had not told posterity this, but for their ignorance, who choose that circumstance to commend their friend by, wherein he most faulted."[15]

This theme of blots and bloodstains recurs in the Sonnets to such a degree that Hickey theorized that the real author was also attainted:

- "When, in disgrace with fortune and men's eyes, I alone beweep my outcast state...Yet in these thoughts myself almost despising," (26); "So shall these blots that do with me remain" (36); "I am attainted" (88); and especially Sonnet 109:

- "So that myself bring water for my stain.

- Never believe, though in my nature reign'd

- All frailties that besiege all kinds of blood

- That it could so preposterously be stain'd"

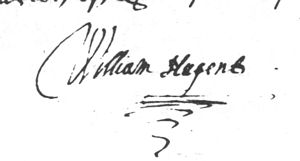

When William Nugent was attainted he wrote:

- "the stain now abiding in my name which makes me ever loathsome unto myself may be wiped away...The most unfortunate and hateful to himself, William Nugent."[16]

References

- ^ Calendar of Carew Manuscripts, op.cit. under 1593, p.86:

- ^ Nugent, op.cit. p. 37. Original reference is from Calendar of Carew Manuscripts op.cit. under 1584, p.380

- ^ Acts of the Privy Council in Ireland, p.167. The last reference is via The Green Cockatrice op.cit. p.188. This kidnapping is also mentioned in the Calendar of the State Papers relating to Ireland under the 12th of December 1573 p. 533

- ^ Fr John Lynch, Supplementum Alithinologiae (St Omer, 1667).

- ^ Nugent, p. 31

- ^ See the new DNB article under Thomas Radcliffe. See also: "In 1572 Thomas Radcliffe, Earl of Sussex, became Lord Chamberlain and his troupe of actors then performed at court, and did so until he died in 1583, often as the Lord Chamberlain's Men" (Hugh M. Richmond, Shakespeare's theatre: a dictionary of his stage context (London, 2002), p.446).

- ^ See p. 62 of these Chronicles

- ^ See Raymond Hickey, Irish English: History and Present-day Forms (Cambridge, 2007) ISBN 0-521-85299-4. Note also that Ben Jonson in his Irish Masque at Court lampoons the Irish accent, showing that Hiberno-English was already distinctively different from normal English at the time of Shakespeare.

- ^ UJA vol 5 1857 p. 92.

- ^ UJA vol 5 1857 p. 156.

- ^ T F Healy shakes/Shakes.htm American Mercury (1940)

- ^ See also Michael Cronin, Shakespeare tradition and the Irish Language an article in Mark Burnett, Shakespeare and Ireland (1997), p.202.

- ^ As in Basil Iske, The Green Cockatrice (Tara, 1978), p.96.

- ^ An example can be seen in the Cecil Papers at Hatfield House: "William Nugent to the King. He has previously exhibited petitions for his "restitution to bloode" in the next Irish Parliament, and for a fee farm of £30 of concealed lands. The King has granted the fee farm but not the other request. Because of this he has not been able to enjoy the full benefit of the King's grant. He asks that letters ordering his restitution in blood in the next Irish Parliament be sent to the Irish Government, so that he may leave for Ireland with some token of royal favour." (Calendar of the Manuscripts of the Most Honourable Marquess of Salisbury, London, 1973, Vol 23, p.188, December 24, 1604)

- ^ Discoveries Made Upon Men and Matter and Some Poems by Ben Jonson

- ^ Lord Deputy Perrot to Lord Burghley 4 Dec 1584, Public Record Office Northern Ireland (PRONI) D/3835/A/5/40, quoted in Nugent, p. 205

- C-Class biography articles

- Automatically assessed biography articles

- WikiProject Biography articles

- C-Class Ireland articles

- Low-importance Ireland articles

- C-Class Ireland articles of Low-importance

- Ireland articles needing infoboxes

- All WikiProject Ireland pages

- C-Class Shakespeare articles

- Low-importance Shakespeare articles

- WikiProject Shakespeare articles

- Wikipedia Did you know articles