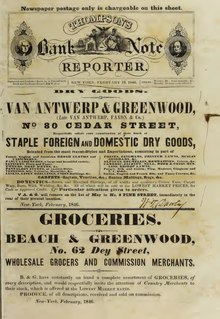

Thompson's Bank Note Reporter

1846 issue of Thompson's | |

| Categories | bank note reporter |

|---|---|

| Frequency | twice-weekly |

| Founder | John Thompson |

| First issue | 1842[a] |

| Final issue | c. 1884 |

| Based in | New York City |

| OCLC | 19648725 |

Thompson's Bank Note Reporter was a periodical published in New York City by John Thompson beginning in 1842. As a bank note reporter, its main purpose was to convey information about the notes issued by each of the hundreds of different banks operating in North America at the time, including the discounts at which their notes traded, and descriptions of counterfeits currently in circulation. Thompson's was considered the pre-eminent bank reporter in the country, and, as of 1855, claimed a circulation of 100,000, higher than any of its competitors.[1]

Circulation[edit]

Thompson's offered the following subscription options:[2]: 239

- Twice-weekly for $5 per year[2]: 239

- Weekly for $3[2]: 239 [3]

- Twice-monthly for $2[2]: 239 [3]

- Monthly for $1[3]

The publication's audience included bankers and merchants ranging from New York City to the western states.[2]: 239–240 One Wisconsin banker recalled that "the merchant in his store or the peddler on the prairies would as soon think of doing their business without scales, measure, or yardstick as without a Thompson's, or some other bank note reporter of recent date".[1]

Format[edit]

The front page of the reporter typically contained a small number of editorials and breaking financial news.[2]: 240 The remainder of the publication mostly consisted of an exhaustive listing of banks, organized by state. For each bank, the reporter would generally include:

- The discount at which its notes traded, as a percentage. For example, the figure "1⁄2" would mean that a $1 note from that bank was trading for 99.5 cents worth of gold.[4]: 77 [better source needed]

- Descriptions of any counterfeits of the bank's bills currently in circulation

- The name of the bank's president and cashier[1]

Furthermore, some banks would be marked as closed or fraudulent, indicating to the reader that their bills were worthless. Others were annotated as being likely to fail.

The reporter sometimes included facsimiles of counterfeit plates which were considered especially dangerous.[3]

Publication history[edit]

Thompson's was published from Wall Street in New York City. Its founder, John Thompson, had been working as a bill broker there since 1832, previously having worked dealing lottery tickets.[1]

The first issue of the reporter was published in 1842.[a] A notice in the New-York American on December 31, 1841 announced it as "a new Weekly Paper, under the title of Thompson's Bank Reporter, in pamphlet form, containing sixteen pages" to be issued beginning January 4, 1842. At the time of its debut, there were two other noteworthy existing bank note reporters being published in the city, one of them by Archibald McIntyre.[1]

Initially announced as a weekly paper to be issued on Saturdays, by March 1842, it was being published twice-weekly, on Wednesdays and Saturdays.[1]

At some point before 1849, the reporter was renamed The Bank Note & Commercial Reporter. By 1858, it was circulating under the title Thompson's Bank Note and Commercial Reporter.[1]

By 1866, as the free banking era came to a close, the traditional function of bank reporters became obsolete, and Thompson's character shifted toward that of a "bank directory".[1]

In 1876, a bank note reporter published from 1864 by L. Mendelson as the National Bank Note Reporter (and later as The National Bank Note Reporter and Financial Gazette) was merged with Thompson's.[1]

Final years[edit]

Thompson's reporter seems to have ceased publication around 1884 or 1885, though accounts of this time are conflicting.

In July 1884, the New York Times published an exposé uncovering a large-scale blackmail scheme in which the publishers of Thompson's Reporter had, for years, been sending letters to banks around the country requesting payment for subscriptions or advertisements in the reporter, threatening to give them a negative rating if they did not comply. According to the Times, while Thompson's Reporter had, under John Thompson, been "the pioneer in [its] class of journalism" and "a standard guide to the business", Thompson had sold off the paper some 20 years earlier, and it had subsequently changed hands multiple times. The paper's current owner was unknown, but reputed to be one "L. P. Haver" (in later articles, named variously as either "Lewis" or "Louis" P. Haver). A Times reporter found Haver at the offices of the Reporter, where he vehemently denied the charges of blackmail, and accused the complaining banks of attempting to evade paying their bills.[7] The Times published a number of follow-ups in 1884, detailing further allegations of malfeasance, and on August 17 1884, reported that Haver and another manager of Thompson's Reporter, J.E. Callinan, had been indicted on blackmail charges.[8] Ultimately, Haver was convicted of a misdemeanour and, in October 1885, a judge imposed a fine of $500; he was spared a prison sentence in light of his agreement that he would retire from publishing the paper.[9]

According to a profile of Charles David Steurer in the 1896 biographical compilation Men of the Century, an Historical Work, the facility at which Thompson's was printed was destroyed in a fire in 1884. (The 1884 New York Times blackmail exposé states that the paper had previously been located at the original headquarters of the New York World at 37 Park Row—now the site of the Potter Building—until it burned down in 1882, causing $1,500 of damages for Thompson's.) It goes on to state that Steurer, who had been managing the printing of Thompson's at the time, formed the publishing house Stumpf & Steurer with friend Anthony Stumpf in 1855, and began publishing a new bank directory similar to Thompson's under the title The American Bank Reporter. At the same time, they also established a weekly financial newspaper, The American Banker.[10]

As of 1887, an advertisement by "Anthony Stumpf & Co., Publishers" described The American Bank Reporter as being "Formerly Thompsons & Underwoods Bank Reporters, (Consolidated.)", with The American Banker described as "a 24 page weekly financial journal published in connection with" the Reporter.[11]

American Banker, which continued in print into the 21st century, has been regarded as a successor to Thompson's Bank Reporter.[5][12]

Related publications[edit]

Thompson also published a bank note list, Thompson's Bank Note Descriptive List, which was offered for free to annual subscribers. The list was updated at irregular intervals, and by 1865 26 revised editions had been published.[3]

A collection of facsimiles of hundreds of gold and silver coins in circulation, The Coin Chart Manual, was published as a supplement to Thompson's reporter as early as 1848, and continuing until at least 1877. It was also offered for free to annual subscribers to the reporter, with standalone copies sold for 12.5 cents.[1]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b Dillistin, the most comprehensive source on the history of Thompson's Bank Reporter and bank reporters, broadly, gives 1842 as the year of the paper's first issue, supported by the contemporary prospectus quoted from the New-York American.[1] Furthermore, the earliest digitized copy of the reporter, dated September 24, 1842, is labelled "No. 52", which is consistent with bi-weekly publication having begun that year. However, a number of sources related to the newspaper American Banker, which claims descent from Thompson's, give 1836 as the year of the reporter's first issue.[5] At least one source gives the year as 1841.[6]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Dillistin, William H. (1949). Bank note reporters and counterfeit detectors. American Numismatic Society.

- ^ a b c d e f Mihm, Stephen (2009). A Nation of Counterfeiters: Capitalists, Con Men, and the Making of the United States. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674032446.

- ^ a b c d e Smith, Arthur A. (December 1942). "Bank Note Detecting in the Era of State Banks". The Mississippi Valley Historical Review. 29 (3): 371–386. doi:10.2307/1897916. JSTOR 1897916.

- ^ Gorton, Gary B. (2015). The Maze of Banking: History, Theory, Crisis (PDF). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190204839.

- ^ a b Gordon, John Steele (15 January 2021). "Chasing Down History". ABA Banking Journal.

- ^ Broome, Lissa Lamkin (2005). "The First One Hundred Years of Banking in North Carolina". NC Banking Inst. p. 108.

- ^ "Country Bank Leeches". New York Times. 31 July 1884.

- ^ "Rascals Brought to Book". New York Times. 17 August 1884.

- ^ "Haver Pays a Fine of $500". New York Times. 30 October 1885.

- ^ Morris, Charles (1896). Men of the Century, an Historical Work: Giving Portraits and Sketches of Eminent Citizens of the United States. I. R. Hamersly & Company. p. 70.

- ^ "Stumpf & Co advertisement". Hastings Daily Gazette-Journal. 18 March 1887. p. 2.

- ^ Terrell, Ellen (14 March 2017). "For the Latest on Counterfeit Money". Library of Congress Blog.