Titanic navigation bridge

On the Titanic, the navigation bridge (or command bridge) was a superstructure where the ship's command was exercised. From this location, the officer on watch determined the ship's geographical position, gave all orders regarding navigation and speed, and received information about everything happening on board.

The bridge was composed of various compartments: a navigation shelter where watch was kept, and the wheelhouse where a wheel was located, known as the helm in maritime language, which steered the rudder and transmitted orders to the engines, also called a chadburn. On either side to starboard and port of the navigation shelter, two exterior wings allowed for maneuvers. There was also a chart room and the captain's watch room. The bridge was also connected to officers' cabins, which varied in comfort according to rank. It was also close to the wireless telegraphy room. Six officers took turns on watch duty on the bridge, accompanied by quartermasters and other members of the deck crew. The second officer and the captain could also be present if the situation so required.

On April 14, 1912, around 11:40 p.m., decisions to attempt to avoid the iceberg were made from the bridge. After the collision, the order to evacuate the ship was also decided on the bridge. Crushed by the fall of the first funnel, then by that of the foremast, little remained of the bridge when the wreckage of the Titanic was discovered in 1985.

Location[edit]

The bridge was the "brain" of the liner and was located in the most appropriate place, in line with the ship's direction of travel, i.e. forward of the boat deck.[1] Situated sixty metres from the bow, the navigation bridge rises some twenty-three metres above the waterline. This gives officers a clear view of the front of the ship and the horizon.[2]

The bridge was accessible from the boat deck on the port and starboard sides. Staircases located forward allow access from either side of promenade deck A. It also communicated with the officers' wardroom, located aft of the wheelhouse, at the level of the first funnel.[3] However, access was reserved for officers in charge of navigation and crew members on watch at sea.

Infrastructures[edit]

Gangway shelter[edit]

At the forward end of the boat deck, there was a shelter and two manoeuvring fins. A railing connected them, lining the front of the deck. The bridge shelter was airy and open on both sides to the officers' promenade. Nine windows gave the helmsman and navigation officers an unobstructed view of the foremast and bow.[4]

Auxiliary helm and course compass[edit]

Under the bridge shelter there was an auxiliary steering wheel for the Titanic's rudder. It was used during harbour entrances and exits, so that the helmsman, working in open space, could more easily hear the successive orders of the manoeuvring officers. The auxiliary helm was also used along the coast, in good weather or hot conditions. It was mechanically connected to the main rudder.[2]

A course compass, manufactured in Glasgow, was located opposite the auxiliary helm, so that the helmsman could see it at all times. The instrument consisted of a wooden base (cockpit) topped by a magnetic compass, fitted with an internal oil light. It indicated the ship's course. In addition, a rudder angle indicator (axiometer) was fixed to the ceiling of the bridge shelter. This electrical indicator told the helmsman the precise angular position of the rudder in relation to the ship's axis. The third officer, Herbert Pitman, was in charge of checking the compass, correcting the compass course with the help of the deviation curve. The officer relied on the bearing compass, located on a platform on the boat deck, between the second and third funnels, in the centre of the liner. Navigation could be astronomical, using the stars and the sun. An identical compass and the main helm were located in the wheelhouse.[4]

Order transmitters[edit]

The bridge shelter contained five telegraphs. These transmitted orders to various installations on the liner. Two of them were connected to the engine room, two others to the gangway. The last was an emergency telegraph, which also communicated with the engine room. It was only used if the other two failed.[2]

The telegraphs connected to Titanic's engine room were used by the officer of the watch or the commanding officer to communicate any orders concerning forward and astern speed.

Forward, the possible orders were, in ascending order of power, Dead Slow, Slow, Half, Full.

The "STOP" command instructed the engine room to stop propeller rotation.

The Stand By command meant that the machine had to be ready. The Dead Slow, Slow, Half and Full commands indicated different levels of propeller revolutions per minute (i.e. power required).

Towards the rear, the power commands were identical.

The Finished With Engines command indicated that the machines were no longer required.

Wheelhouse[edit]

Operation[edit]

The wheelhouse was an innovation in ship steering at the beginning of the 20th century. On the Titanic, it enabled the helmsman to steer the ship at night, or in cold temperatures. The wheelhouse had five windows arranged so that the view could be extended through the nine windows in the bridge shelter. The helmsman stood on a small platform to maximise his view of the course compass in front of him and the bow of the ship.[2]

At night, the wheelhouse was completely closed, the blinds on the five windows were lowered and the helmsman relied on the course compass and the orders of the officer of the watch. The purpose of this total closure of the wheelhouse was to enable the quartermaster to concentrate on the course compass, preventing distraction from any outside light. Similarly, the order transmitters were designed to be lit from inside at night, but this lighting was deactivated when the ship was on the high seas, as orders were less common.[5]

Telephone system[edit]

The wheelhouse was equipped with a set of four horn telephones. These were used to communicate with four of the ship's installations, to ensure smooth navigation. The forecastle, crow's nest, engine room and docking gangway were all linked to the wheelhouse. On the evening of the collision, the watchman Frederick Fleet used the telephone in the crow's nest to warn the bridge of the presence of the iceberg.[6]

In addition to these telephone installations, Titanic was equipped with a switch to close the watertight doors. On the night of the sinking, this switch was operated by First Officer William Murdoch, closing the compartments.[7] There could have been an indicator, but only the testimony of a sailor confirms this.

Other installations[edit]

In addition to the telephone system, the wheelhouse also included an underwater signal receiver, capable of warning the ship of the approach of a dangerous area. This system worked by means of two boxes, each containing a microphone, placed inside the hull, below the waterline, on the port and starboard sides. Connected to the receiver in the wheelhouse, these boxes received noises identified by bells of different tones, over a distance of up to 20 miles. This indicator was useful when approaching a dangerous place, but also for navigating in fog, as it allowed the liner to be located in relation to the signals picked up.[8]

Titanic's wheelhouse was also equipped with a speed indicator and a clinometer to measure the ship's angle of heel. Lastly, it was equipped with two pendulums, sextants, marine chronometers, thermometers and barometers.[2]

Officers' accommodation[edit]

At the back of the wheelhouse, at the level of the first funnel and accessible from the boat deck, were arranged the accommodations for the eight navigating officers. The entirety of these accommodations was designated as the "officers' quarters". The captain had the most luxurious apartments, a set of three rooms, a personal bedroom, a lounge, and a bathroom, located on the starboard side. The apartments of the fourth officer and a smoking room were situated on the same side.

On the port side, a corridor provided access to the apartments of the second officer, the first, second, third, fifth, and sixth officers. The navigation room was a meeting space for the captain and his officers for all matters concerning navigation. The chart room, located just behind the wheelhouse on the port side, contained numerous map portfolios and nautical documents, as well as the two master clocks. These clocks controlled the forty-eight clocks distributed throughout the entire ship. These two main clocks (or marine chronometers) required daily evaluations of their running, as they were never reset to protect their delicate mechanism. For example, while sailing towards America, the clocks gained half an hour each day of navigation. Every day at noon, the fourth officer Joseph Boxhall recorded the time discrepancies in the "chronometer log". The chart room also contained the International Code of Signals, as well as the Titanic's logbooks and navigation charts. The harbor pilot's cabin adjoined the chart room on the starboard side. It was used during port entries and exits. When pilots boarded the liner, they went to this cabin with the captain to advise on the maneuvers to be carried out.

Finally, the officers had at their disposal a bathroom located opposite radio room.[2]

Radio room[edit]

The radio room, whose radio operators were Jack Phillips[9] (chief operator) and Harold Bride[10] (assistant operator), was located about 12 m from the forward end of the boat deck, behind the first funnel. It communicated with the bridge via a passageway to port of the officers' quarters. It consisted of three rooms.

The room furthest to port was known as the "salle sourde", which contained the radio transmission equipment and an emergency transmitter. From the roof of the "salle sourde", was a 50 m high vertical radiating radio wire linking four horizontal wires to form the T-shaped antenna. This was where the radio receiver and control equipment were located. Finally, the room furthest to starboard was a rest room, equipped with a bunk. During the voyage, the two radiotelegraph operators took it in turns to ensure a permanent listening watch by wireless telegraphy on the 600 metre waveband[11] from the Titanic. At night, Jack Phillips, the chief operator, was on watch from 8 pm to 2 am, while his colleague Harold Bride was on watch from 2 am to 8 am.[12] During the day, the men took turns for mutual convenience, always ensuring a continuous watch. The operators shared the toilets and showers with the navigation officers. They also had a small lounge on C deck.[13]

Radiotelegraphic correspondence[edit]

Normally since 1903[Note 1] for the exchange of radiotelegraphic correspondence with ships at sea: ships such as the Titanic transmitted on a wavelength of 300 metres (1,000 kHz) and listened on a wavelength of 600 metres (500 kHz).[14] (Coast stations normally transmitted on a wavelength of 600 metres and listened on a wavelength of 300 metres). Ships and coast stations were able to transmit and receive on the same wavelength; for example a ship contacting another ship on the 600 metre wavelength or a ship broadcasting weather information or iceberg positions on the 600 metre wavelength.

Docking gangway[edit]

Overlooking the third-class promenade deck, the Titanic's stern bridge was a facility for manoeuvring the ship to dock or handling it in confined spaces. It was arranged transversely to the stern deck and, unlike the main bridge, was not sheltered. It had several facilities, similar to the wheelhouse.[15]

It was equipped with two telegraphs linked directly to two of the order transmitters on the navigation bridge, so that they operated in pairs. One pair was used to communicate orders to the engine room, while the other transmitted manoeuvring and steering orders. It also included Titanic's third steering wheel (along with the one under the bridge shelter and the one in the wheelhouse), used in the event of failure of the main wheel's remote control motor. Finally, the stern bridge had a course compass.[2]

The petty officers were responsible for taking it in turns. On 14 April 1912, George Rowe was on watch. He spent the evening walking and talking to the passengers to keep active and warm, when at around 11.40 pm he was surprised to see an iceberg pass alongside the ship. Remaining at his post, it was only three-quarters of an hour later that he was informed of the situation, when he telephoned fourth officer Joseph Boxhall to tell him that he had just seen a canoe leave. He then returned to the ship's bridge where he helped fire distress rockets until 1:25 am. Then, at 1:40 am, he was put in charge of folding raft C, and survived the sinking.[16]

Command of the ship on its only crossing[edit]

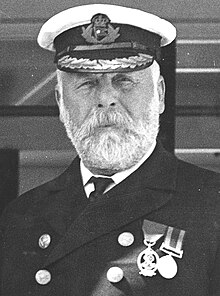

The crew assigned to command the ship consisted of eight navigation officers. Captain Edward John Smith, in command of Titanic, and his second-in-command Henry Wilde supervised a team of six navigation officers,[17] who were responsible for navigating the ship according to their watch.

The captain reported directly to three "senior" officers, who were responsible for the navigation of the Titanic according to their watch. The three most senior officers designated for these tasks were the Executive Officer, Henry Wilde, First Officer William McMaster Murdoch and Second Officer Charles Lightoller.[2] William Murdoch was to have been Titanic's second in command, but at the last minute Henry Wilde was imposed, demoting Murdoch to first officer and Charles Lightoller to second officer. All three men had already sailed on the Titanic's sister-ship, the Olympic; this last-minute change had the advantage of assigning to the Titanic three sailors already experienced in manoeuvring such a ship.[18] David Blair, originally second officer, left the liner.[19]

These three men took turns every four hours 13, and had under their command two 'junior' officers, who worked in pairs. Depending on the watch, the two junior officers supervised by a senior officer are Herbert Pitman, third officer[20] and Harold Lowe, fifth officer;[21] or Joseph Boxhall, fourth officer [22] and James Paul Moody, sixth officer.[23]

The officers were also responsible for reporting important events in the bridge diary, located in a small room at the back of the wheelhouse, the chart room. Wilde was generally in charge of this task[24] Titanic's helm was entrusted to one of the seven petty officers of the deck crew, who reported to a senior officer.

The night of the sinking[edit]

Collision[edit]

On the evening of 14 April 1912, at 11.40pm, while the Titanic was travelling at 22.5 knots,[25] an iceberg was spotted by the crow's nest watchmen Frederick Fleet and Reginald Lee. The senior officer of the watch was William McMaster Murdoch; the junior officers were Joseph Boxhall and James Paul Moody. Frederick Fleet immediately rang the crow's nest bell three times, then telephoned the wheelhouse.[26] The sixth officer, Moody, took the call: Fleet alerted him to the presence of an iceberg less than 500 metres in front of the ship.

Moody immediately informed First Officer Murdoch, who ordered the helmsman in the wheelhouse to turn to starboard: "Hard a'starboard ".[26] With this order, Murdoch tried to turn the ship to port. Using the order transmitters, he also ordered the engine room to go astern: "Full astern".[1] However, after the sinking, the chief engineer stated that the order transmitter was indicating "STOP".[27] The Titanic finally hit the iceberg, which blew the rivets of the hull below the waterline over five compartments, opening up an ingress of water. Using the control in the wheelhouse, Murdoch closed the ship's watertight doors. Shortly afterwards, the captain, who was in his quarters, was woken up by the shock and asked First Officer Murdoch for a report. He also asked for the engines to be completely shut down and for Fourth Officer Boxhall to assess the damage.[28] However, Boxhall did not notice anything unusual. The captain then ordered a survey of the ship by the Titanic's architect, Thomas Andrews. Andrews drew up a prognosis after going down with the captain and his first officer Henry Wilde to the lower decks to see the damage. The captain asked Fourth Officer Boxhall to warn Officers Lightoller and Pitman, who had remained in their quarters. All the officers gathered in the navigation room with Thomas Andrews, who announced that the ship was doomed.[29]

Assignment of officers to lifeboats[edit]

Orders were given to lower the lifeboats and to send radio messages from the station near the officers' quarters.

The evacuation of the passengers in the lifeboats was organised as follows: First Officer William Murdoch was in charge of all the lifeboats on the starboard side (i.e. all the odd-numbered lifeboats plus the A and C lifeboats) and Second Officer Charles Lightoller was in charge of all the lifeboats on the port side (all the even-numbered lifeboats plus the B and D lifeboats).[30] The other officers had to assist Murdoch and Lightoller in their tasks. At 0:55 am, Third Officer Pitman helped to fill the No 5 lifeboat and then boarded it to take command.[31]

Second-in-command Henry Wilde was carefully involved in loading the boats, but Charles Lightoller took control of operations, having had experience of a previous shipwreck.[32] At around 1.30 am, Wilde ordered fifth officer Harold Lowe, who had come to help fill canoes 14 and 16, to board canoe 14.[33] James Paul Moody, the sixth officer, assisted fifth officer Lowe[34] but declined the offer of a place in the boat. The fourth officer, Boxhall, boarded lifeboat No. 2 at around 1:45 am.[35]

Operators Jack Phillips and Harold Bride sent distress messages until water flooded the radio room shortly after 2:10.[36] Two hours and thirty minutes after the collision with the iceberg, the water reached the bridge shelter and the wheelhouse at around 2:15am.[37]

Commander Smith and his second-in-command Wilde, as well as officers Murdoch and Moody, disappeared in the wreck; their bodies were never recovered. Charles Lightoller survived by joining folding raft B, a few minutes before the Titanic disappeared beneath the waves. He was in the company of Archibald Gracie.[38] He was the most senior officer to survive the sinking.

At around 4.10 am, the first lifeboat was picked up by the RMS Carpathia. It was standard lifeboat no. 2, under the command of Joseph Boxhall. Dinghy no. 12 was the last boat recovered. Charles Lightoller was the last survivor to board.[39]

State of the installations on the wreck[edit]

After sinking, the Titanic crashed violently to the bottom of the ocean at a depth of almost 3,700 metres. The bridge shelter and wheelhouse were damaged by the fall of the first funnel, then destroyed as the ship fell to the ocean floor. The foremast collapsed onto the port gangway railing.[40]

The crow's nest, shown in the 1986 photographs, has now disappeared, probably having fallen inside the hull.[41] The bronze control formerly attached to the main helm is still present.[42] The officers' quarters and adjacent rooms are in better condition, particularly Commander Smith's cabin.[43] However, the roof of the radio room is pierced in several places, having been used as a landing platform for submersibles. In 2000, an expedition made it possible to refloat the foot of the wheelhouse bar.[44] In 2017, a study published by the BBC revealed that the entire wreck could disappear within twenty years.[45] In 2020, an American survey confirmed that the walls of the navigation bridge, the officers' quarters and the radio room had been completely dissolved.[46]

On the Olympic and the Britannic[edit]

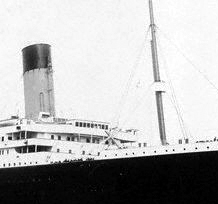

Titanic wais the second of the three Olympic class ships. In fact, it benefited from improvements over its predecessor, the Olympic, and the lessons learned from the sinking led to a rethink of the gangways on the two surviving sister ships.[47]

On board the Olympic, the officers' quarters were organised differently and were smaller.[3] The change in organisation came from Joseph Bruce Ismay's idea of adding a few first-class cabins on the deck of the Titanic's boats.[48] The shape of the wheelhouse also differed from those on the Titanic and Britannic. However, it was later modified.[49] A platform for a compass was also placed on top of the wheelhouse following the redesign.

The Britannic, which was still under construction when Titanic sank, had its gangway redesigned. The panel for the watertight bulkheads no longer indicated whether they were closed or open, but clearly indicated their position. The order transmitters had also been improved, and a device indicated the precise number of revolutions of the ship's engines. As on the Olympic after her refit, the bridge roof housed a compass.[50] Communication between the bridge and the radio room, which had been lacking on board the Titanic, was improved by means of a pneumatic tube linking the two installations. On the Olympic, this link was made by telephone.[51]

See also[edit]

Notes and references[edit]

- ^ a b Marshall (1997, pp. 18–19)

- ^ a b c d e f g h Le Site du Titanic (n.d.a)

- ^ a b Le Site du Titanic (n.d.b)

- ^ a b RMS -Titanic Inc. (n.d.a)

- ^ Titanic, Marconigraph. (n.d.a)

- ^ Le Site du Titanic (n.d.c)

- ^ Titanic-Titanic (n.d.)

- ^ Chirnside (2004, p. 28)

- ^ Encyclopedia Titanica (n.d.a)

- ^ Encyclopedia Titanica (n.d.b)

- ^ Washington: Government Printing Office (1907)

- ^ Brewster & Coulter (1999, p. 37)

- ^ Le Site du Titanic (n.d.d)

- ^ Washington: Government Printing Office (1907b)

- ^ RMS Titanic Inc. (n.d.b)

- ^ Encyclopedia Titanica (2002)

- ^ Le Site du Titanic (n.d.e)

- ^ Dane (2019)

- ^ Chirnside (2004, p. 137)

- ^ Encyclopedia Titanica (n.d.c)

- ^ Encyclopedia Titanica (n.d.d)

- ^ Encyclopedia Titanica (n.d.e)

- ^ Encyclopedia Titanica (n.d.f)

- ^ Brewster & Coulter (1999, p. 16)

- ^ Riffenburgh (2008, p. 32)

- ^ a b Ferruli & Mahé (2003, p. 94)

- ^ Titanic, Marconigraph (n.d.b)

- ^ Piouffre (2009, p. 142)

- ^ Chirnside (2004, p. 160)

- ^ Ferruli & Mahé (2003, p. 152)

- ^ Piouffre (2009, p. 157)

- ^ Lightoller (1935)

- ^ Piouffre (2009, p. 161)

- ^ Gracie (1998, p. 138)

- ^ Gracie (1998, p. 152)

- ^ Ferruli & Mahé (2003, p. 235)

- ^ Ferruli & Mahé (2003, pp. 238–239)

- ^ Gracie (1998, pp. 184–196)

- ^ Ferruli & Mahé (2003, p. 268)

- ^ Legag (n.d.)

- ^ Le Site du Titanic (n.d.f)

- ^ Trésors du Titanic (n.d.)

- ^ Brewster & Coulter (1999, p. 82)

- ^ Chirnside (2004, p. 294)

- ^ Rebillat (2017)

- ^ Rebillat (2020)

- ^ Brewster & Coulter (1999, pp. 78–79)

- ^ Association française du Titanic (n.d.)

- ^ Chirnside (2004, p. 77)

- ^ Hospital Ship Britannic (n.d.)

- ^ Chirnside (2004, p. 225)

Notes[edit]

- ^ 1903 Radiotelegraph Convention in Berlin by nine countries.

Bibliography[edit]

- Brewster, Hugh; Coulter, Laurie (1999). Tout ce que vous avez toujours voulu savoir sur le "Titanic". Fortunes de mer. Grenoble Toronto (Ontario): Glénat Madison press books. ISBN 978-2-7234-2882-8.

- Chirnside, Mark (2004). The Olympic-class ships: Olympic, Titanic, Britannic. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-2868-0. OCLC 56467242.

- Ferruli, Corrado; Mahé, Patrick (2003). "Titanic": l'histoire, le mystère, la tragédie. Paris: Chêne-EPA. ISBN 978-2-85120-106-5.

- Gracie, Archibald (1998). Rescapé du "Titanic". Paris: Ramsay. ISBN 978-2-84114-401-3.

- Marshall, Ken (1997). Au coeur du "Titanic". Tournai] [Paris: Casterman. ISBN 978-2-203-15606-7.

- Piouffre, Gérard (2009). Le Titanic ne répond plus. L'histoire comme un roman. Paris: Larousse. ISBN 978-2-03-584196-4.

- Riffenburgh, Beau (2008). Toute l'histoire du Titanic: la légende du paquebot insubmersible. Bagneux: Sélection du "Reader's digest". ISBN 978-2-7098-1982-4.

- Le Site du Titanic (n.d.). "La passerelle de navigation du Titanic". titanic-1912.fr. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

- Le Site du Titanic (n.d.a). "Plan du pont des embarcations". Le Site du Titanic.

- RMS -Titanic Inc. (n.d.a). "Wheelhouse and bridge".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Titanic, Marconigraph. (n.d.a). "FAQ (Movie Fiction)". Titanic, Marconigraph.

- Le Site du Titanic (n.d.c). "L'installation téléphonique du Titanic". titanic-1912.fr. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

- Titanic-Titanic (n.d.). "Titanic's bridge and Wheelhouse". Titanic-Titanic.com.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Encyclopedia Titanica (n.d.a). "Jack Phillips : Titanic Wireless Operator". www.encyclopedia-titanica.org. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

- Encyclopedia Titanica (n.d.b). "Harold Sydney Bride : Titanic Survivor". www.encyclopedia-titanica.org. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

- Washington: Government Printing Office (1907a). "Berlin International Wireless Telegraph Convention: November 3, 1906". earlyradiohistory.us. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

- Le Site du Titanic (n.d.d). "La station radio du Titanic". titanic-1912.fr. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

- Washington: Government Printing Office (1907b). "Service regulations, annexed to the 1906 Berlin International Radiotelegraph Convention". earlyradiohistory.us. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

- RMS Titanic Inc. (n.d.b). "Third class poop deck with aft docking bridge". RMS Titanic Inc.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Encyclopedia Titanica (2002). "George Thomas Rowe : Titanic Survivor". www.encyclopedia-titanica.org. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

- Le Site du Titanic (n.d.e). "Le Personnel de Pont du Titanic". titanic-1912.fr. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

- Dane, Kane (2019). "Titanic's Officer Reshuffle". Titanic-Titanic.com. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

- Encyclopedia Titanica (n.d.c). "Herbert John Pitman : Titanic Third Officer". www.encyclopedia-titanica.org. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

- Encyclopedia Titanica (n.d.d). "Harold Godfrey Lowe : Titanic Fifth Officer". www.encyclopedia-titanica.org. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

- Encyclopedia Titanica (n.d.e). "Joseph Groves Boxhall : Titanic Survivor". www.encyclopedia-titanica.org. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

- Encyclopedia Titanica (n.d.f). "James Paul Moody : Titanic Victim". www.encyclopedia-titanica.org. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

- Titanic, Marconigraph (n.d.b). "STOP Command / "Porting Around" Maneuver". titanic.marconigraph.com.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Lightoller, Charles Herbert (1935). Titanic and other ships. Oxford: Oxford City Press. ISBN 978-1-84902-733-5.

- Legag (n.d.). "Photos de l'épave du Titanic". legag.com. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

- Le Site du Titanic (n.d.f). "La partie avant de l'épave du Titanic, en 2004". titanic-1912.fr. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

- Trésors du Titanic (n.d.). "La passerelle". Trésors du Titanic.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Rebillat, Clémentine (2017). "L'épave du Titanic va disparaître définitivement". parismatch.com (in French). Retrieved 2024-04-05.

- Rebillat, Clémentine (2020). "L'épave du Titanic bientôt découpée? La justice autorise une nouvelle expédition". parismatch.com (in French). Retrieved 2024-04-05.

- Association française du Titanic. "Pont supérieur du Titanic". aftitanic.free.fr. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

- Hospital Ship Britannic (n.d.). "RMS Britannic Boat deck". Hospital Ship Britannic.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

External links[edit]

- (fr) Le Site du "Titanic", site dedicated to the liner; in particular this page devoted to the navigation bridge.

- Titanic's Bridge And Wheelhouse, description of the gangway on Titanic-Titanic.com.

- Wheelhouse and Bridge on the website of RMS Titanic INC, the company responsible for operations on the wreck.