Traditional Councils in the Yap State

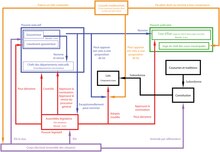

The traditional councils of the Yap State are two assemblies of traditional leaders: the Pilung Council for the chiefs of the Yap Islands and the Tamol Council for the chiefs of the Outer Yap Islands. They have been established in 1992 by the Constitution of the Yap State, within the Federated States of Micronesia. The executive, the legislative, the judiciary and the traditional councils are the four institutional branches of government in the Yap State, but the councils, unlike the others, transcend the concept of the separation of powers. The councils are responsible for exercising the functions that relate to tradition and custom, which are not required to be recorded in the written law. In the Yap State, custom and tradition prevail over any interpretation of the constitution and even over any judicial decision. The councils have the right to veto legislation that they consider to be contrary to traditional practices. The constitutionality of these councils and their veto power could be challenged under the Micronesian Federal Constitutional Law, but to this date no one has done it.

The council leaders have great influence over the resignation of government officials they deem to be in violation of the law and over the selection of candidates for governor and lieutenant-governor of the Yap State. The councils meet periodically to discuss matters relating to customs and traditions, provide advice to those who come to them for consultation and approval, and organize cultural and heritage events. The local communities consider the traditional leaders to be the legitimate arbiters of truth in matters of tradition and custom, and as the protectors of the people.

Customs and traditions: a piece of identity[edit]

Each of the Constitutions of the Federated States of Micronesia, Yap, Chuuk, Pohnpei and Kosrae, and even some of the Constitutions of municipalities such as Lukunor and Namoluk in the Chuuk State, recognize and protect to varying degrees the role and legal legitimacy of customs and traditions.[1] At the federal level, the Constitution envisages the creation of a House of Chiefs made up of traditional leaders or elected representatives. However, this project, initiated in the late 1970s by the states of Pohnpei and Yap,[1] has not been successful so far.[2]

The people of the Yap State preserved a solid set of customs and traditions despite long foreign domination (by the Spanish, Germans, Japanese, and then Americans) and in spite of the depopulation caused by the diseases brought by Europeans and external cultural influences.[3] The State of Yap is the only one to have attributed an institutional position to the traditional chiefs.[1] This is unique in the Pacific.[3] Traditionally, Yapese chiefs had complete power over land and authority over everyone. In the past, they also had the power of life and death.[3]

The Constitutional framework of the traditional Yapese Councils[edit]

The Constitutions of the Federated States of Micronesia and the Yap State recognise and enforce the interdependence of legal and traditional rights.[4] The Yap State Constitution recognises four branches of government: the executive, the legislature, the judiciary, and traditional leaders.[3]

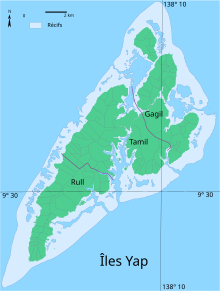

The first section of Article III of the Yap Constitution, added in 2006 by an amendment, recognises the role in traditions and customs of the Dalip pi Nguchol[5]. They are the three paramount chiefs of the Yap Islands, who own the three most valuable lands in the islands and under whose authority all the villages, which themselves have chiefs, are divided into three nug.[3][6][7] Traditionally, the Yap Islands have always had a higher status than the outer Yap Islands, a by-product of the inter-island hierarchical system of sawei, which disappeared in the early 20th century.[3][8] In the Yap society, the owner of the most valuable land (according to traditional land hierarchy) becomes the traditional chief.[6][8] In the outer islands of Yap, the eldest man, or in some cases the woman of the oldest matrilineal lineage, is considered the island's or atoll's chief.[8] To ensure that traditions and customs are respected and maintained, the second section of Article III of the Constitution established in 1982 the existence of two councils of chiefs: one for the chiefs of the municipalities of the Yap Islands, the Pilung Council, and the other for the chiefs of the municipalities of the outer Yap Islands, the Tamol Council.[3][5][9][10] The latter is therefore legally considered to be equal to that of the Yap Islands, whereas traditionally it is subordinate to it.[11]

In the Yap Islands, the term pilung, which in Yap means "many voices" (pii - many, lung - voice), is used to refer to the village chief, i.e. the highest ranking landowner in a village.[7] The term Tamol is a generic term used in the outer islands of Yap to refer to a chief.[12][13][14]

The third section of Article III states that nothing in the Constitution shall be interpreted as limiting or invalidating recognized traditions or customs.[3] Custom and tradition take precedence over any statute, any interpretation of the Constitution, and even any judicial decision.[3] According to the lawyer Brian Z. Tamanaha, "Unlike the other three branches, however, councils transcend the separation of powers by exercising quasi-legislative, quasi-executive, and judicial functions, not to mention the leadership role".[3]

The legal mandate of traditional councils is somewhat opaque and can be interpreted in a variety of ways. It is commonly accepted that their role is to maintain and preserve the Yapese cultural heritage, including yalen u Wa'ab, i.e. customs and traditions.[10] Article V, Sections 16 to 18 of the Constitution empowers them to perform functions that relate to tradition and custom in the state and to review and disapprove acts of the Yap State Legislature if it violates what they consider to be customs and traditions.[3][9][10] Tradition is not codified but is passed on orally.[4][note 1] This veto power, which the councils use sparingly, cannot be overridden.[9] If the lawmakers wish to proceed, they must incorporate the objections into the bill, send it back to the assembly for consideration, and then, if passed, back to the councils for approval.[9] To avoid a deadlock, the council may read the bill prior to the assembly's review.[3] In 1982, during the Yap Constitutional Convention, the veto power, inherited from the 1978 Yap District Charter, was the subject of intense debate. The convention's Standing Committee, which was the proposing body, rejected it in favour of a text requiring that only bills relating to custom and tradition be referred to the Councils and that they should only comment on bills, not disapprove.[3] The convention's delegates rejected this recommendation.[3]

Constitutionality of the Councils[edit]

The Constitution of the Federated States of Micronesia states that the four constituent states must have a democratic government, guaranteed by elections for the Yap State. However, this fundamental principle is potentially violated by the existence of a formal role for traditional leaders and the primacy of traditional rights.[3][9] The primacy of traditional rights was already articulated in the Yap District Charter, enacted in 1978 by the Yap District Legislative Assembly under the administration of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands.[3] However, a provision in the Constitution of the Federated States of Micronesia acknowledges the customary rights, the privileges of traditional leaders and their right to govern their people.[9] According to human rights lawyer Tina Takashy, in Micronesia, collective rights take precedence over individual rights, which are only considered necessary or useful for a stated purpose or objective.[4]

The constitutionality of the two traditional councils has never been questioned, neither by Japanese nationals who, according to Micronesian statesman John Haglelgam, would not dare to do so, nor by the Yapese who, according to Haglelgam, believe that voting is a foreign concept imposed on them by the outside world and do not regard it as a natural right.[9] Lawyer Brian Tamanaha believes that if the council veto was declared unconstitutional, as it contradicts the need for democratic power articulated in the Federal Constitution, the institutional power of traditional leaders would be significantly weakened.[3] In the summer of 1990, a federal constitutional convention proposed legislation to create a House of Chiefs. In 1991 the Micronesian electorate rejected it, particularly in the Yap State. Sociologist Glenn Petersen suggests that many Micronesians, and particularly the Yapese, are acutely aware of the differences between chieftaincy and statehood, and want to preserve the role of traditional leaders as protectors of the people, to maintain competing power blocs, and not to have federal power alone imposed on them (although they do recognise its merits[2][15]). Many observers believe that the House of Chiefs system is not a good one. For many observers, the Yapese system is a viable traditional political system.[2]

How the councils work[edit]

The functioning and appointment of council members are operated by the assemblies.[16] The Pilung and Tamol Councils are composed of the high chiefs or their representatives from each municipality of the Yap Islands or districts of the outer Yap Islands.[10] Within each municipality, the village chiefs choose from among the senior chiefs who will represent them on the Pilung Council. In the case of competing chiefs, influence and kinship determine the winner.[8] The municipality of Rull is the only one that holds an election to choose its chief in the council, but those who have held the position are high-ranking chiefs.[8] For the Tamol Council, the head of the municipality is the head of the corresponding island or atoll.[8] The changes in the composition of the councils must be reported for registration to the State Court, the Legislative Assembly, and the Governor.[16]

The Pilung Council chiefs meet weekly at their central office in Colonia while the Tamol Council chiefs meet once or twice a year on the Yap Islands.[8][17][18] Each year the Legislative Assembly allocates funds for the operation of the councils.[16] The Pilung Council has received since 1987 an allowance of $1,000 for expenses, including the possible employment of administrative assistants. The Tamol Council leaders are paid a daily allowance for each day of meetings and receive less in total than the Pilung Council leaders.[8][16] None of the council members receive a salary.[8][16]

The use of power by traditional councils[edit]

The councils vetoed appropriation bill proposals because it violated customs and traditions.[9] In the mid-1980s, the Pilung council vetoed a proposal for providing a bus in a municipality because it was not traditional to run a bus in one municipality and not in others.[8] As permitted by the Yap State Code, councils may advise and make recommendations to departments and offices of the executive branch of the state government or provide assistance to municipalities and islands.[16] They have the power to hold oversight hearings, forcing the state governor, his cabinet, or the entire administration, to justify their policies and actions. According to former President of the Federated States of Micronesia John Haglelgam, the effectiveness of the councils is limited because their members are relatively uneducated.[9] They can, however, force the resignation of all or part of the government if, for example, there is criticism towards the councils.[9]

The support of the councils play a key role in the election of the governor and lieutenant governor. Generally, the Tamol council members work with and defer to the Pilung council leaders. Since the implementation of the Constitution in 1984, candidates for these two positions have been mainly chosen by the councils and have always run without opposition.[8][9] No traditional leader has ever run for such a position. In some elections, chiefs from the outer islands voted on behalf of the people. Few Yapese object the influence of the councils and chiefs on the electoral processes. A popular joke is that no Yapese will miss the governor and lieutenant-governor if they get lost at sea.[9]

The support of the councils is also recommended for the position of Yap State Senator. The only one who did not have it was John Haglelgam (born in Eauripik), who in 1987 ran against the councils' candidate for the Congress of Micronesia, (the forerunner of the Congress of Federated States of Micronesia), and got elected. The councils were disowned by the voters.[8] The Pilung Council supported him and the Tamol Council was more reluctant to do so because of resentment among its members. John Haglelgam was elected President of the Federated States of Micronesia by his three fellow State Senators on 11 May 1987.[8] In 1990, there was rumour that the support of the Tamol Council was eroding, as the President had not given them enough time during an official visit. In 1991, he lost the elections for the position of State Senator and was therefore unable to run for a second term as president.[8]

In 1987, the chiefs of the Tamol council were, at their request and without any specific training, appointed as municipal judges.[17] As almost exclusive landowners on the islands of which they are chiefs, they are obliged to act as intermediaries for the state for public services.[17] The Yap State Code entrustes the traditional councils with the promotion and preservation of traditions and customs.[16] The Yap Day cultural event, a major event in the state, is organised by a committee where two of the five seats are reserved for the Pilung Council members. In practice, the Pilung Council controls many aspects of the event, including the dance performances. While the committee suggests dances, the council has authority over which dance is to be performed by which village and determines the remuneration received by the dancers.[19]

At the end of March 2019, nine of the ten Pilung council members demanded the expulsion of the American journalist Joyce McClure, who moved to the Yap Islands, accusing her of disseminating false information that could disrupt the state's security.[20][21][22] McClure published articles about attempts by a foreign company to bribe Yap State governors and lieutenant governors, which they themselves revealed,[23] and about fishing licence cases around Ulithi that led to the removal of the Tamol council member Chief Fernando Moglith.[24][25] The Yapese legislators rejected the expulsion on April 30, as they considered the request inappropriate and outside the council's jurisdiction. High-ranking members of the administration raised the issue of possible manipulation of the traditional chiefs by outsiders.[26]

The creation of the councils has to some extent transformed the exercise of traditional authority and the way it is used to serve the community.[10] In wishing to protect traditional authority by incorporating it into the government, the Yapese have also intrinsically altered it.[11] For example, there were previously strict protocols for interactions between chiefs and their assemblies.[10] As anthropologist Stefan M. Krause reports, "Now chiefs meet regularly in a central office to receive a minor stipend, which is mainly for administrative tasks performed for the state. They seem to be stuck in a dynamic where their power is mainly used to approve or disapprove of the activities and practices of the state. They have neither the economic resources nor the legal authority to do much more".[10] The funding they request for their cultural heritage projects is systematically refused.[10] For Stefan M. Krause, the state has appropriated the traditional authority of the chiefs by incorporating them into their disciplinary institution.[10] He deplores the fact that the councils' action is limited by their institutional position and believes that strengthening the power of the traditional councils would enable them to manage heritage practices more effectively.[10]

The Pilung Council in the public debate[edit]

Traditional councils are rarely the subject of public debate. In the early 2010, a large section of the population opposed the establishment of a giant 10,000-room casino hotel by a Chinese company on the Yap Islands, which has since been abandoned. In this case, the Pilung council at one point negotiated with the foreign investors and one of its members may have received a bribe.[27][6] The debate, which has been very divisive in the country, resulted in the traditional authority of some council members being challenged, with critics wanting only the highest-ranking landowning chiefs to sit on the council, rather than individuals chosen to replace them because of their age or wisdom about traditions and customs. Despite this, the vast majority of the population consider the councils to be the legitimate arbiters of truth in matters of yalen u Wa'ab.[10]

Notes[edit]

- ^ According to Tina Takashy, within the household, this can lead to abuses and violations of human rights when the objective is to ensure the protection of social cohesion and harmony and common survival.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Gonzaga Puas (2016). The Federated States of Micronesia's Engagement with the Outside World: Control, Self-Preservation, and Continuity (PDF). Canberra: Australian National University. pp. 52–54.

- ^ a b c Petersen, Glenn (2015-12-15). "At the Intersection of Chieftainship and Constitutional Government: Some Comparisons from Micronesia". Journal de la société des océanistes (141): 255–265. doi:10.4000/jso.7434. ISSN 0300-953X. S2CID 131488868.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Tamanaha, Brian Z. (1988). The Role of Custom and Traditional Leaders under the Yap Constitution. University Hawai'i law review. pp. 81–104.

- ^ a b c Takashy, Tina (2009-06-01). "Federated States of Micronesia: Country Report on Human Rights". Victoria University of Wellington Law Review. 40 (1): 25–36. doi:10.26686/vuwlr.v40i1.5376. ISSN 1179-3082.

- ^ a b Constitution of the state of Yap. Gouvernement des États fédérés de Micronésie. 1982. p. Article 3.

- ^ a b c Donald Rubinstein; Clement Yow Mulalap (2014). "Yap Paradise Island": A Chinese Company's Proposal for Building a 10,000-Room Mega-Resort Casino Complex. Canberra: Australian National University. pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b Ushijima, Iwao (1987-03-25). "Political Structure and Formation of Communication Channels on Yap Island : A Case Study of the Fanif District". Senri Ethnological Studies (in Japanese). 21: 177–203. doi:10.15021/00003252. ISSN 0387-6004.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Pinsker, Eve C.; Lindstrom, Lamont (1997). "Traditional leaders today in the Federated states of Micronesia". In White, Geoffrey M. (ed.). Chiefs today: traditional pacific leadership and the postcolonial state. East-West Center series on contemporary issues in Asia and the Pacific. Stanford (Calif.): Stanford University press. pp. 150–182. ISBN 978-0-8047-2849-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Haglelgam, John (1998). Traditional leaders and governance in Micronesia », State society and governance in Melanesia. Vol. 98. Text included in (en) John Haglelgam, « Big men », within Brij V. Lal, Kate Fortune, The pacific islands : an encyclopedia, vol. 1, Honolulu, Hawaï, 2000, p. 273-276. pp. 1–7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Stefan M. Krause (2016). The Production of Cultural Heritage Discourses: Political Economy and the Intersections of Public and Private Heritage in Yap State, Federated States of Micronesia. University of South Florida. pp. 282–286.

- ^ a b Meller, Norman (1980). "On matters constitutional in Micronesia". The Journal of Pacific History. 15 (2): 83–92. doi:10.1080/00223348008572390. ISSN 0022-3344.

- ^ William E. Lessa (1980). More tales from Ulithi atoll : A content analysis. Berkeley: University of California press. pp. 17, 20, 32, 52. ISBN 0-520-09615-0.

- ^ Paul D'Arcy (2006). The People of the Sea: Environment, Identity, And History in Oceania. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i. pp. 146, 152, 160. ISBN 978-0-8248-2959-9.

- ^ William H. Alkire (1965). Lamotrek Atoll and Inter-island Socioeconomic Ties. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. p. 165.

- ^ Petersen, Glenn (2009-06-30), "Micronesia and Micronesians", Traditional Micronesian Societies, University of Hawai'i Press, pp. 183–196, doi:10.21313/hawaii/9780824832483.003.0002, ISBN 9780824832483

- ^ a b c d e f g "Yap State Code, Councils of Traditional Leaders". www.fsmlaw.org. Gouvernement de l’État de Yap. 1979.

- ^ a b c Brian Z. Tamanaha (1993). Understanding Law in Micronesia : An Interpretive Approach to Transplanted Law. Leide: E. J. Brill. pp. 20–24. ISBN 9004097686.

- ^ "Yap hosts Council of Tamol meeting". www.mvariety.com. 7 September 2011.

- ^ Aoyama, Toru (2001). "Yap day : cultural politics in the state of Yap" (PDF). Kagoshima University Research Center for the Pacific Islands, Occasional Papers. 34: 1–13.

- ^ Mar-Vic Cagurangan (19 April 2019). "Holding the line; in support of Joyce McClure". www.pacificislandtimes.com. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ "Yap's traditional chiefs seek to expel, gag probing US journalist". asiapacificreport.nz. 22 April 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ "Chiefs in FSM's Yap demand journalist's expulsion". www.radionz.co.nz. 19 April 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ Joyce McClure (28 February 2019). "Anonymous gifts left for new Yap leaders revealed". www.pacificislandtimes.com. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ Joyce McClure (28 February 2019). "Chinese target Yap fish with some local help". Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ Joyce McClure (6 March 2019). "Traditional Yap chief axed for fishing deals with outsiders". Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ "Yap legislature rejects 'kick out' demand over US journalist". asiapacificreport.nz. Multimedia Investments. 3 May 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- ^ Bill Jaynes (2013). "Yap legislature calls for cancellation of ETG foreign investment permit". www.fm/news. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

Bibliography[edit]

- Tamanaha, Brian Z. (1988). The Role of Custom and Traditional Leaders under the Yap Constitution. University Hawai'i law review. pp. 81–104.

- Pinsker, Eve C. (1997). "Traditional leaders today in the Federated states of Micronesia". In White, Geoffrey M. (ed.). Lamont Lindstrom, Chiefs today : Traditional Pacific leadership and the Postcolonial State. Stanford, Stanford university press. pp. 150–182.

- Haglelgam, John (2000). "Big men". In Lal, Brij V.; Fortune, Kate (eds.). The pacific islands : an encyclopedia. Vol. 1. Honolulu, Hawaï. pp. 273–276. ISBN 0-8248-2265-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Krause, Stefan M. (2016). The Production of Cultural Heritage Discourses: Political Economy and the Intersections of Public and Private Heritage in Yap State, Federated States of Micronesia. University of South Florida. pp. 282–286.