User:-A-M-B-1996-/sandbox

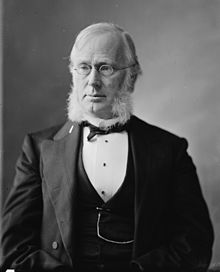

George Frisbie Hoar | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Massachusetts | |

| In office March 4, 1877 – September 30, 1904 | |

| Preceded by | George S. Boutwell |

| Succeeded by | Winthrop M. Crane |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts | |

| In office March 4, 1869 – March 3, 1877 | |

| Preceded by | John Denison Baldwin |

| Succeeded by | William W. Rice |

| Constituency | 8th district (1869–73) 9th district (1873–77) |

| Member of the Massachusetts Senate | |

| In office 1857 | |

| Member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives | |

| In office 1852 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 29, 1826 Concord, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | September 30, 1904 (aged 78) Worcester, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Political party | Free Soil (before 1855) Republican (after 1855) |

| Other political affiliations | Radical Republicans Half-Breeds |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Louisa Spurr (m. 1853) Ruth A. Miller (m. 1862–1903) |

| Relations | Samuel Hoar (father) Ebenezer R. Hoar (brother) Sherman Hoar (nephew) |

| Children | 3, including Rockwood |

| Alma mater | Harvard University Harvard Law School |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Signature | |

George Frisbie Hoar (August 29, 1826 – September 30, 1904) was a prominent American attorney and politician who served as United States Senator from Massachusetts from 1877 to 1904.

Born into an extended New England political family that included Founding Father Roger Sherman and multiple members of Congress, Hoar was first a member of the anti-slavery Free Soil Party before becoming a founding member of the Republican Party.

After his election to Congress in 1868, Hoar became known as a Radical Republican on the issue of Reconstruction and member of the Half-Breed faction, an informal grouping of moderate but partisan Republicans who opposed the political patronage system, particularly as practiced under President Ulysses S. Grant.[1]

In the final decade of his life, he became a leading anti-imperialist critic of the Spanish-American War, the annexation of Hawaii, and American military occupations abroad, particularly in the Philippines.

Early life[edit]

George Frisbie Hoar was born in Concord, Massachusetts on August 29, 1826, the youngest of six children born to Samuel and Sarah (née Sherman) Hoar. His father was a nationally famous anti-slavery attorney and politician and friend of Ralph Waldo Emerson. His mother was the youngest daughter of U.S. Senator and Founding Father Roger Sherman and his second wife, Rebecca Minot Prescott.

He studied for several months at a boarding school in Waltham, Massachusetts run by Samuel and Sarah Bradford Ripley.[2] He graduated from Harvard University in 1846 and earned his law degree at Harvard Law School in 1849.

Legal career[edit]

He was admitted to the bar and settled in Worcester, Massachusetts, where he practiced law. He moved to Worcester in part because it was the stronghold of anti-slavery sentiment in the state, the home of so-called "Conscience" Whigs (a term coined by George's elder brother Ebenezer),[3] as opposed to Boston's pro-South "Cotton" Whigs, who were ambivalent on the issue of slavery.[4]

He joined in partnership with Emory Washburn, who turned the practice over to Hoar when Washburn was elected Governor of Massachusetts in 1854. The firm soon became Devens & Hoar, one of the largest in Worcester County.[5]

Massachusetts politics (1848–68)[edit]

In 1848, Samuel and Ebenezer R. Hoar were among the founding members of the new Free Soil Party of Massachusetts, founded in revolt against the Whig nomination of General Zachary Taylor, a slaveholder.[6] The party held its first convention in Worcester, and George Hoar joined his father and brother in the campaign.[4] Nevertheless, Hoar remained a dedicated constitutionalist, equally opposed to "cowardice" of the northern Whigs and the radicalism of abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison.[7] He was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives as an avowed-Free Soiler in 1852.[8] During his brief time in the House, he spoke in support of regulating the hours of labor.[9]

On September 20, 1855, Hoar was among those in attendance at Worcester City Hall for the "mass convention" marking the birth of the Massachusetts Republican Party.[10] Hoar at first tacitly supported, then opposed, a proposed electoral fusion of the Republicans with the anti-immigration American Party, the dominant force in Massachusetts politics from 1854–56.[11]

Hoar was elected to the Massachusetts Senate in 1857 as a Republican.[4] During his one-year term in the State, he chaired the Judiciary Committee.[12]

Civil War[edit]

Before, during, and after the Civil War, Hoar was an avid supporter of abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner.[13] He took an active role in the 1860 campaign for Abraham Lincoln, giving the keynote address at the Worcester County convention and directing the Republican campaign in the county that secured a large majority for the Lincoln ticket.[9]

During the Civil War, Hoar considered asking Governor John Albion Andrew for a commission to serve, but upon request of his law partner, Charles Devens, Hoar remained in Worcester to maintain their practice. Instead, he spent the war advocating on behalf of local soldiers, assisting them in receiving commissions and transfers. He served on the county committee on enlistments and raised money to furnish "extra comforts" for the local regiment.[14]

Hoar advocated for the War as a proper means to achieve the abolition of slavery throughout the Union. Hoar, by association with Sumner and Andrew and his continued anti-slavery activism, came to be seen as a Radical Republican. In 1862, Charles Devens ran against Andrew for Governor, pitting the partners at Devens & Hoar against each other; Andrew won.[15]

On two occasions during the War, Hoar was nominated for Mayor of Worcester but declined the nomination.[16][17]

U.S. House of Representatives (1868–77)[edit]

In 1868, Hoar's political friends and influential Worcester manufacturers promoted him for the Republican nomination to represent Worcester in Congress. Hoar was aware of their efforts, but abstained from actively seeking the nomination, as was common practice at the time.[18] He spent the summer campaign in England on an extended vacation.[19]

For one term during his House service, from 1873 to 1875, his brother Ebenezer R. Hoar served alongside him.

Hoar undertook an active study of labor politics during his time in the House. During an 1871 tour of England, Hoar collected research on British labor conditions and trade unions and followed the formation and collapse of the Paris Commune in the newspapers. [20]

Reformism and rivalry with Benjamin Butler[edit]

Throughout his career, Hoar consistently opposed the practice of patronage and machine politics, which he viewed as corrupt. As a Representative, this placed him in opposition to the powerful Republican Stalwarts. Through their control of the Senate, the Stalwarts controlled political appointments; by extension, they controlled the Grant administration and the Republican Party.[21]

Hoar's opposition to the Stalwarts came despite his loyal partisanship and may have originated in the removal of his elder brother Ebenezer R. Hoar as President Grant's Attorney General, at the behest of Senator Conkling and fellow Massachusetts Representative Benjamin Butler. Though Grant proposed to nominate the elder Hoar to the Supreme Court, Conkling and Butler refused their support. In addition to his increasing suspicion of the Stalwart faction, the Hoars began a personal political rivalry with Representative Butler. In 1871, George Hoar openly campaigned against Butler's nomination for Governor at the Republican state convention.[22]

In 1872, Hoar opted not to join the Liberal Republican campaign against Grant, unlike his idol Sumner. Instead, Hoar argued that although the President's allies were corrupt, Grant personally remained a man of honorable character and the Republican Party remained true to its pre-Civil War principles.[23]

In 1873, Butler launched another campaign for Governor and control of the Massachusetts Republican Party. Hoar's criticisms became more pointed and more public; he summarized Butler's career in three words: "swagger, quarrel, failure." Hoar's campaign was successful, and the party nominated William B. Washburn over Butler.[24]

Despite his defeat, Butler remained an influential figure in Washington and a close personal friend of President Grant. Butler's influence over Grant strained Hoar's faith in the President, particularly following the congressional investigation of the Crédit Mobilier scandal, which Hoar urged on.[25] Hoar was the chief author of an investigative committee report declaring that the federal government had the power to reform and reorganize the Union Pacific railroad.[26]

In his fourth term, the House (now controlled by the Democratic Party) voted to impeach Grant's former Secretary of War, William W. Belknap. Hoar was appointed to prosecute the impeachment before the Senate as a House manager. He argued that although Belknap had resigned from office, impeachment was necessary and just to prevent him from holding federal office again. Hoar failed to convince Republican Senators in sufficient numbers to achieve the necessary two-thirds majority.[27]

1876 election[edit]

In the 1876 election, Hoar focused his efforts on opposing the campaign of "Ultra Stalwart" Senator Roscoe Conkling, the boss of the New York Republicans. Among Conkling's opponents, Hoar preferred Attorney General Benjamin Bristow, a symbol of anti-corruption, over Speaker of the House James G. Blaine, whose motivations were attributed to a personal rivalry against Conkling. If the convention deadlocked between the three, Hoar hoped to promote his friend, Representative William A. Wheeler.[28]

Hoar vigorously campaigned to unify the anti-Conkling forces in Massachusetts and to send an anti-Stalwart delegation to the nominating convention in Cincinnati. In May, he honored both Bristow and Blaine at a dinner at the Wormley Hotel and accepted a position as a delegate-at-large to Cincinnati.[29] However, anti-Conkling unity was threatened by accusations of corruption against Blaine. More reformist Bristow supporters, including Hoar, thereafter ruled out support for Blaine. In return, it became increasingly unlikely that the Blaine delegates would support Bristow on a second or third ballot. Hoar focused his attention on boosting Wheeler.[30]

On the convention's first ballot, Blaine finished a decisive first, ending Bristow's hopes and threatening the Stalwarts, but without sufficient delegates to be nominated in his own right. Fearing of a Blaine nomination, the Stalwarts threw their support to Governor of Ohio Rutherford B. Hayes, a proclaimed reformer. Hoar was satisfied by the choice of Hayes and further encouraged by the nomination of Wheeler for Vice President.[31]

The general election between Hayes and the Democratic candidate, New York Governor Samuel Tilden, produced a disputed result. Though Hayes apparently led in electoral votes, Democrats challenged the Republican victories in Florida, South Carolina, and Louisiana. A joint committee of Congress was formed to consider potential resolutions to the dispute; Hoar was among the seven House members appointed. Unable to find any constitutional provision or precedent, the committee suggested the establishment of a special Electoral Commission to rule on the disputed electors, which Hoar also served on. In every case, Hoar voted to certify the Republican electors.[32]

U.S. Senator (1877–1905)[edit]

1877 election[edit]

In June 1876, Hoar publicly declared his intention to retire from the House at the end of his term. Privately, he began to consider a challenge to incumbent U.S. Senator George S. Boutwell, President Grant's former Secretary of the Treasury. Boutwell had the backing of General Butler's machine, and Hoar gained the support of anti-Butler men in the state, along with former Free Soilers, business interests, self-declared independents, and young Republicans. Henry L. Dawes, Massachusetts's other United States Senator, publicly stayed out of the race but privately expressed his support to Hoar. After seven ballots, Hoar defeated Senator Boutwell to win the seat.[33]

Hayes administration (1877–81)[edit]

During his first term in office, Hoar established himself as a key supporter of the Hayes administration, a personal confidant of President Hayes, and a national figure in his own right. Hayes appointed Hoar's old law partner, Charles Devens, as Attorney General of the United States and Hoar's cousin, William M. Evarts, as Secretary of State. Using his Senatorial privilege over appointments, Hoar set about clearing Massachusetts federal offices of the Butler men who had been appointed under Grant, notably installing Alanson W. Beard to the powerful office of Collector of the Port of Boston.[34]

1880 presidential election[edit]

In 1880, Hoar once more sought to block the Stalwarts from the presidency, this time in the person of ex-President Grant, who ran seeking an unprecedented third term in office. He promoted Vermont Senator George F. Edmunds for the nomination and secured a full slate of Massachusetts delegates in support of Edmunds.[35] At the convention, Hoar was elevated to chairman by a coalition of Half-Breeds and supporters of James Blaine.[36]

When James Garfield, who eventually won the party's nomination and the presidential election, rose to object that votes were being cast for him without his consent, Hoar disallowed his objection as out of order. Hoar later said, "I was terribly afraid that he would say something that would make his nomination impossible."[36][37] Garfield was nominated on the thirty-sixth ballot after Blaine supporters abandoned their candidate in his favor. Conkling ally Chester A. Arthur was chosen as his running mate, and the ticket was successful in the fall.[38]

Garfield and Arthur administrations (1881–85)[edit]

Hoar began the Garfield administration with high hopes. He was rumored for the position of Secretary of State and confidently predicted eight years in office for President Garfield. Though the State Department post went to Blaine, Hoar approved, and Garfield appointed Horace Gray, Hoar's lifelong friend and law school classmate, to the next vacancy on the Supreme Court.[39] Hoar's confidence in Garfield soared after he appointed William H. Robertson to the office of Collector of the Port of New York, against the wishes of Conkling and fellow New York Senator Thomas C. Platt. Conkling and Platt both resigned in protest.[40]

Hoar's hopes were dashed with Garfield's assassination and death on September 19, 1881. Chester Arthur, Conkling's close ally, would now become President. James Blaine was removed as Secretary of State, and Alanson Beard was replaced as Collector of the Port of Boston.[41] However, Arthur did pursue civil service reform in Garfield's stead, signing the Pendleton Civil Service Act in 1883. Though Hoar, like his colleague Dawes, preferred decentralized merit reform, as opposed to a British system of centralized bureaucracy, the urgency of the issue led him to support the Pendleton Act over Dawes's proposed alternative.[42] Hoar did tangle with Arthur over the 1882 River and Harbor Act, a system of internal waterway improvements which passed over Arthur's veto with Hoar's support,[43] and tariff legislation.

Hoar also began to lose his grip on the state party, which nominated Robert R. Bishop in 1882 over Senators Hoar and Dawes's preferred choice of William W. Crapo. Bishop ultimately lost to Hoar's old nemesis, Benjamin F. Butler, now a Democrat.[41] Despite his diminished position, Hoar was re-elected to the Senate in 1883 over weak opposition from John Davis Long and Butler, who failed to join their forces against him. Arthur, despite distaste for Hoar, made little effort to unseat him. Senator Dawes worked actively on Hoar's behalf, emphasizing his importance to manufacturing interests. After three ballots, Hoar was re-elected.[44] Butler lost re-election in 1883.

1884 presidential election[edit]

In 1884, Hoar nominally supported Senator George F. Edmunds in opposition to both Arthur and James Blaine. Unlike in 1876 and 1880, however, the tactic proved unsuccessful. Blaine was nominated as the best alternative to Arthur, and Hoar supported him in the general election against Grover Cleveland.[45] Hoar's defense Blaine's character and record in rebuttal to Carl Schurz was one of the most cited Republican documents during the 1884 campaign.[46]

Hoar did not consider bolting the Republican Party with the Mugwumps, despite their common political and social backgrounds; two of his own nephews, Sherman and Samuel Hoar, endorsed Cleveland. He considered the Mugwumps' support of Cleveland a betrayal of principle and their citation of political independence a façade to cover their opposition to tariff protections and the rights of freed Black southerners. He blamed his nephews' switch on Harvard President Charles W. Eliot.[47] Cleveland ultimately won the election, becoming the first Democratic president since the Civil War.

Cleveland and Harrison administrations (1885–97)[edit]

Cleveland's victory strengthened Hoar's partisan resolve. He continued to advocate for active protection of Black civil rights in the South and was firmly resistant to Cleveland's effort to weaken the protective tariff, including by a reciprocal treaty with Canada.[48] However, Hoar found common ground with Cleveland on currency policy and successful efforts to repeal the Tenure of Office Act and pass legislation regulation presidential succession and electoral vote counting.[49]

In 1888, Hoar once again led the Massachusetts delegation to the Republican convention. His preferred candidate was John Sherman, followed by Walter Q. Gresham, Benjamin Harrison, William B. Allison, and finally Blaine. He briefly supported a May boom for General Philip Sheridan, but no candidacy materialized, Sheridan's health declined, and he ultimately died in August.[50] At the convention, Hoar determined that neither Sherman nor Gresham could win. After he unsuccessfully tried to convince Sherman to withdraw in favor of William McKinley, Hoar settled on Harrison. He lobbied the eastern delegations to support Harrison and was successful in stampeding their votes to nominate Harrison on the eighth ballot.[51] Harrison was ultimately elected in a campaign emphasizing the tariff issue.[52] Hoar gave a major address in his support at Harvard University's Tremont Temple in October.[53]

During the Harrison presidency, Hoar made his final stand on behalf of the cause of Black suffrage. Working with Senator John Coit Spooner and Representative Henry Cabot Lodge, Hoar drafted a bill to supervise state voter registration and election procedures. It also empowered federal courts, which were predominantly controlled by Republicans, to review electoral disputes. The bill passed the House by a party-line vote, but its consideration was delayed in the Senate by the debate over the Sherman Silver Purchase Act.[54] Though the bill's primary opponents were Democrats led by Arthur Pue Gorman, it was ultimately derailed by Republican National Chairman Matthew Quay of Pennsylvania, who felt it urgent to pass a tariff increase before the 1890 elections.[55] Despite Hoar's pleas, the elections bill was put off until after the November elections, which resulted in a landslide for the Democrats and dashed any hope for Hoar's bill. In the lame duck session of 1890–91, the elections bill was set aside to meet the demands of Western senators, led by Henry Teller and William M. Stewart, who argued the 1890 landslide showed the public demanded more silver legislation. Despite Hoar's strenuous efforts, the Hoar-Spooner bill never came to a vote.[56]

In 1892, President Cleveland was returned to office and, with partisan control of the Senate split, Hoar was removed as chair of the Judiciary Committee and relegated to an office in the Capitol basement.[57] As a minority Senator, Hoar focused his efforts on unsuccessfully blocking Cleveland's calls for tariff reform and the income tax amendment.[58]

McKinley administration (1897–1901)[edit]

Hoar voted in favor of the Dingley Tariff, though he was critical of its high tariff on raw wool, which was borne by New England textile manufacturers.[59]

––––PAGE 207—————

Roosevelt administration (1901–05)[edit]

Views[edit]

In general, Hoar's biographer Richard Welch described him as an ardent moral reformer but suspicious economic or institutional reforms. His caution stance on reform became more conservative after the rise of the Populist movement and the nomination of William Jennings Bryan in 1896.[60]

Currency and banking[edit]

Hoar was a "hard money man" throughout his public life, advocating for specie rather than paper currency. Hoar's opposition to paper money intensified after his rival Benjamin Butler endorsed fiat paper money in his 1878 gubernatorial campaign. Hoar's position was consistently anti-inflationary and aligned with big business, though he was more sympathetic to proposals for silver currency than he was to paper "greenbacks."[61]

In the wake of the Panic of 1893, Hoar denounced the Populist movement's attacks on the "money trust" as unfounded and conspiratorial. Nevertheless, he was critical of the concentration of wealth and monopoly power. In 1894, he criticized Jacob Coxey's march to Washington and defended the trespass statute under which Coxey was arrested.[62]

Reconstruction[edit]

After the Civil War was won, Hoar advocated for an aggressive Reconstruction policy, arguing that the Confederacy had, in rebelling, "lost their political organizations as States under the Constitution" and were thus "resolved into the condition of unorganized territory" completely subject to the authority of the North, which ought not readmit them until the slaveholding power was broken completely.[63]

Upon his election to the Forty-first Congress, Hoar was quickly recognized as a Radical ally of Senator Sumner. He opposed the readmission of Virginia and Georgia, convinced that their sworn professions of loyalty were unproven, if not completely fraudulent. He supported the Enforcement Act of 1870 and the Ku Klux Klan Act in 1871, both designed to protect the voting rights of emancipated black Americans. In addition to military enforcement of civil rights, Hoar promoted reform of the Southern education system to eliminate lingering inequalities.[64]

Hoar publicly defended President Hayes's controversial decision to withdraw military troops from the South in 1877,[65] but quickly stopped openly supporting reconciliation after Southern whites failed to desist from racial discrimination and intimidation of black voters.[66]

Immigration[edit]

Hoar voted against the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, describing it as "nothing less than the legalization of racial discrimination"[67][68][69][70]

During the 1890s, Hoar was highly critical of the American Protective Association, a nativist anti-Catholic group active in Massachusetts. Hoar publicly defended Catholic immigration and parochial education, citing "the American spirit, the spirit of the age, the spirit of liberty, the spirit of equality, especially what Roger Williams called soul liberty."[71]

Imperialism[edit]

He was a consistent opponent of American imperialism. He did not share his Senate colleagues' enthusiasm for American intervention in Cuba in the late 1890s. On December 1897, he met with Native Hawaiian leaders opposed to the annexation of their nation. He then presented the Kūʻē Petitions to Congress and helped to defeat President William McKinley's attempt to annex the Republic of Hawaii by treaty, though the islands were eventually annexed by means of joint resolution, called the Newlands Resolution.[72]

After the Spanish–American War, Hoar became one of the Senate's most outspoken opponents of the imperialism of the McKinley administration. He denounced the Philippine–American War and called for independence for the Philippines in a 3-hour speech in the Senate, saying:[73][74]

You have sacrificed nearly ten thousand American lives—the flower of our youth. You have devastated provinces. You have slain uncounted thousands of the people you desire to benefit. You have established reconcentration camps. Your generals are coming home from their harvest bringing sheaves with them, in the shape of other thousands of sick and wounded and insane to drag out miserable lives, wrecked in body and mind. You make the American flag in the eyes of a numerous people the emblem of sacrilege in Christian churches, and of the burning of human dwellings, and of the horror of the water torture. Your practical statesmanship which disdains to take George Washington and Abraham Lincoln or the soldiers of the Revolution or of the Civil War as models, has looked in some cases to Spain for your example. I believe—nay, I know—that in general our officers and soldiers are humane. But in some cases they have carried on your warfare with a mixture of American ingenuity and Castilian cruelty. Your practical statesmanship has succeeded in converting a people who three years ago were ready to kiss the hem of the garment of the American and to welcome him as a liberator, who thronged after your men when they landed on those islands with benediction and gratitude, into sullen and irreconcilable enemies, possessed of a hatred which centuries can not eradicate.

Hoar pushed for and served on the Lodge Committee, investigating allegations, later confirmed, of war crimes in the Philippine–American War. He also denounced the U.S. intervention in Panama.

Taxation[edit]

Hoar opposed the institution of a federal income tax as "socialistic" and favoring the landed South over the working people of the North. He celebrated the Supreme Court decision in Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co. which found such a tax unconstitutional.[75]

Trade[edit]

Hoar was an ardent believer in protectionism and opposed the reductions in the Tariff of 1883 and the Wilson-Gorman Tariff.[76][77]

Women's rights[edit]

Hoar also advocated for the rights of women. He was actively involved in the New England Women's Suffrage Association and wrote several of its most popular pamphlets, urged Republican state parties to adopt platforms supportive of woman suffrage in municipal elections, and secured a standing United States Senate committee on women's rights. Though his activism for women's rights waned in later years, his conviction in support of the principle did not.[78]

Labor and business regulation[edit]

As the most active member of the House Committee on Education and Labor, Hoar identified American prosperity with manufacturing growth but rejected the doctrine of Social Darwinism.[79] He also rejected "European" class politics, advocating instead for protection of labor interests for pragmatic reasons; in his view, concessions to labor were necessary to prevent anarchism, socialism, or communism. Upon his return, Hoar introduced a bill "to provide for the appointment of a commission on the subject of the wages and hours of labor and the division of profits between labor and capital in the United States."[20]

Hoar generally voted in the interests of big business and identified the progress of America with its industrialization. He favored protection for creditors in the form national bankruptcy legislation and strong patent law. He wrote: "I look with infinite regret upon everything which shall tend to array the workmen of this country together as a class... Their interest cannot be separated from that of capital."[80]

In 1886, Hoar strongly opposed the Interstate Commerce Act introduced by Senator Shelby Cullom, arguing that government should avoid direct involvement in the contractual relations of businessmen and their customers. Cullom would later accuse Hoar of opposing the bill at the behest of New England industrialists like John Murray Forbes.[81]

Hoar claimed partial credit, along with George Edmunds, for the language of the Sherman Antitrust Act.[82]

Alarmed by the Pullman strike, Hoar proposed that labor unions be infiltrated by sympathetic but tactically conservative members of the professional class to prevent violent strikes.[83]

Native Americans[edit]

Hoar was a strong advocate of the Dawes Act. He justified federal allotment of native lands by comparing Indian relations to that of "a father to his son, or by a guardian to an insane ward..."[84]

Personal life[edit]

Hoar married Mary Louisa Spurr in 1853. They had two children, Mary (1854–1929) and Rockwood Hoar, who represented Massachusetts in the U.S. House of Representatives.[85] Mary Hoar died in 1859.[86]

Hoar remarried to Mary's friend, Ruth Ann Miller, in 1862. They had one daughter, Alice (1864–65), who died in infancy. Ruth Hoar died in 1904, after which George's strength seemed to fade.[86]

He attended the Unitarian Church of All Souls in Washington, D.C.[87] He observed regular church attendance, once saying, "There is, in my judgment, no more commanding public duty than attendance at church on Sunday."[88]

Hoar was an avid outdoorsman and at one point purchased Asnebumskit Hill, the third-highest point in Worcester County after Mount Wachusett and Little Wachusett.[89] He was known for a fondness for birds and a passion for birdsong.[90]

In 1865, Hoar was one of the founders of the Worcester County Free Institute of Industrial Science, now the Worcester Polytechnic Institute.[4]

Hoar was active in the American Historical Association, serving as its president. He was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1853,[91] and served as vice-president from 1878 to 1884, and then served as president from 1884 to 1887.[92] In 1887, he was among the founders of the American Irish Historical Society.[93] He was a regent of the Smithsonian Institution in 1880 and a trustee of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Hoar was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1901.[94] His autobiography, Autobiography of Seventy Years, was published in 1903. It appeared first in serial form in Scribner's magazine.

Through his efforts, the lost manuscript of William Bradford's Of Plymouth Plantation, an important founding document of the United States, was returned to Massachusetts after being discovered in London's Fulham Palace in 1855.[95]

Death and legacy[edit]

Hoar enjoyed good health until June 1904. He died in Worcester on September 30 of that year and was buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Concord. After his death, a statue of him was erected in front of Worcester's city hall, paid for by public donations.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Welch, pp. 1–4.

- ^ Hoar, George F. (1903). Autobiography of Seventy Years. Vol. I. Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 82.

- ^ Welch, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d Dresser, p. 4.

- ^ Dresser, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Welch, p. 7.

- ^ Welch, p. 9.

- ^ Welch, pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b Welch, p. 13.

- ^ Welch, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Welch, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Paine, p. 4.

- ^ Paine, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Welch, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Welch, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Dresser, p. 3.

- ^ Welch, p. 15.

- ^ Welch, p. 20.

- ^ Dresser, p. 5.

- ^ a b Welch, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Welch, pp. 35–37.

- ^ Welch, pp. 38–40.

- ^ Welch, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Welch, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Welch, p. 49.

- ^ Welch, p. 50.

- ^ Welch, pp. 51–54.

- ^ Welch, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Welch, p. 56.

- ^ Welch, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Welch, p. 58.

- ^ Welch, pp. 63–67.

- ^ Welch, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Welch, pp. 73–76.

- ^ Welch, pp. 92–94.

- ^ a b Welch, p. 96.

- ^ Graff, Henry F. (June 26, 1960). "Playing Political Possum Isn't Easy". New York Times. p. 40. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

- ^ Welch, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Welch, pp. 100–01.

- ^ Welch, pp. 103–04.

- ^ a b Welch, p. 105.

- ^ Welch, pp. 108–10.

- ^ Welch, p. 112.

- ^ Welch, pp. 106–07.

- ^ Welch, p. 123.

- ^ Welch, pp. 129–30.

- ^ Welch, pp. 124–29.

- ^ Welch, pp. 132–35.

- ^ Welch, p. 137.

- ^ Welch, p. 139.

- ^ Welch, pp. 139–40.

- ^ Welch, pp. 140–43.

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]], pp. 142–43.

- ^ Welch, pp. 145–47.

- ^ Welch, pp. 150–52.

- ^ Welch, pp. 153–59.

- ^ Welch, p. 172.

- ^ Welch, pp. 177.

- ^ Welch, p. 203.

- ^ Welch, pp. 190–99.

- ^ Welch, pp. 83–88.

- ^ Welch, pp. 181–86.

- ^ Welch, p. 18.

- ^ Welch, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Welch, pp. 76–78.

- ^ Welch, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Daniels, Roger (2002). Coming to America: A History of Immigration and Ethnicity in American Life. Harper Perennial. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-06-050577-6.

- ^ Puleo, Stephen (2007). The Boston Italians. Boston: Beacon Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8070-5036-1.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (March 17, 2017). "135 Years Ago, Another Travel Ban Was In the News". New York Times. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

Taking the ground that the principles embodied in the Declaration of Independence, that all men are created free and equal, is the cardinal principle upon which this Government is established, he went on to declare that no question of policy could be made a pretext for setting it aside to make a distinction against any race of men. He said that all the arguments against the negroes used years ago were now applied to the Chinese.

- ^ https://cpilj.law.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2515/2018/10/3.1-22No-No-No-No22-Three-sons-of-Connecticut-Who-Opposed-the-Chinese-Exclusions-Acts-by-Henry-S.-Cohn-and-Harvey-Gee.pdf

- ^ Welch, pp. 188–93.

- ^ Silva, Noenoe K. (1998). "The 1897 Petitions Protesting Annexation". The Annexation Of Hawaii: A Collection Of Document. University of Hawaii at Manoa. Retrieved December 19, 2016.

- ^ Hoar, George Frisbie (1906). "Subjugation of the Philippines Iniquitous". In William Jennings Bryan (ed.). The World's Famous Orations:America: III (1861–1905). Vol. X. Francis W. Halsey, associate editor (On-line edition published March 2003 by Bartleby.com ed.). New York: Funk and Wagnalls.

- ^ Millard, Candice (February 17, 2012). "Looking for a Fight: A New History of the Philippine-American War". New York Times. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

- ^ Welch, pp. 180–81.

- ^ Welch, pp. 114–16.

- ^ Welch, p. 180.

- ^ Welch, pp. 29–31.

- ^ Welch, p. 119.

- ^ Welch, pp. 117–19.

- ^ Welch, pp. 121–22.

- ^ Welch, pp. 163–64.

- ^ Welch, p. 186.

- ^ Congressional Record, 55th Congress, version 29, part 3 (available at the Library of Congress).

- ^ "Biographical Sketch, Rockwood Hoar". Rockwood Hoar Papers. Boston, MA: Massachusetts Historical Society. Retrieved May 20, 2018.

- ^ a b Dresser, pp. 12–13.

- ^ "Ulysses G. Pierce, Unitarian Leader". New York Times. October 12, 1934. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

- ^ Paine, p. 11.

- ^ Paine, p. 6.

- ^ Paine, p. 8.

- ^ "Members". American Antiquarian Society. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

- ^ Dunbar, B. (1987). Members and Officers of the American Antiquarian Society. Worcester: American Antiquarian Society.

- ^ "History Building Ready". New York Times. April 9, 1940. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter B" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- ^ Hoar, George F. (1905). Autobiography of Seventy Years. Vol. II. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 235ff. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

Additional sources

- United States Congress. "-A-M-B-1996-/sandbox (id: H000654)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress..

- Sherman, Thomas Townsend (1920). Sherman Genealogy Including Families of Essex, Suffolk and Norfolk, England. T. A. Wright. p. 345.

- Nourse, Henry Stedman (1899). The Hoar Family in America and Its English Ancestry. David Clapp & Son.

- George Frisbie Hoar Papers

- George Frisbie Hoar, late a representative from Massachusetts, Memorial addresses delivered in the House of Representatives and Senate frontispiece 1905

Biblography[edit]

- Dresser, Frank Farnum (1917). George Frisbie Hoar. Worcester Fire Society.

- Gillett, Frederick H. (1934). George Frisbie Hoar. Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Hale, Edward Everett (1907). Speeches and Addresses of George F. Hoar. American Antiquarian Society.

- Hoar, George F (1903). Autobiography of Seventy Years. New York: Scribner’s Sons.

- Paine, Nathaniel; Hall, G. Stanley (1905). Memoir of George Frisbie Hoar. Massachusetts Historical Society.

- Welch, Richard E., Jr. (1971). George Frisbie Hoar and the Half-Breed Republicans. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links[edit]

- Works by George Frisbie Hoar at Project Gutenberg

- Error in Template:Internet Archive author: -A-M-B-1996-/sandbox doesn't exist.

- 1826 births

- 1904 deaths

- Activists for African-American civil rights

- Members of the Massachusetts House of Representatives

- Massachusetts state senators

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Massachusetts

- United States senators from Massachusetts

- Politicians from Worcester, Massachusetts

- People of the Spanish–American War

- People of the Philippine–American War

- Presidents of the American Historical Association

- Massachusetts lawyers

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Harvard Law School alumni

- Massachusetts Republicans

- Republican Party United States senators

- Massachusetts Free Soilers

- Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives

- Members of the American Antiquarian Society

- 19th-century American politicians

- Sherman family (U.S.)

- Anti-corruption activists

- American suffragists