User:Alexis Reggae/sandbox3

{{pp-move-indef}} {{pp-dispute}}

Alexis Reggae/sandbox3 | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 2017 | |

| 45th President of the United States | |

| In office January 20, 2017 – January 20, 2021 | |

| Vice President | Mike Pence |

| Preceded by | Barack Obama |

| Succeeded by | Joe Biden |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Donald John Trump June 14, 1946 Queens, New York City, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican (1987–1999, 2009–2011, 2012–present) |

| Other political affiliations |

|

| Spouses | |

| Children | |

| Parents | |

| Relatives | Family of Donald Trump |

| Residence | Mar-a-Lago |

| Alma mater | Wharton School (BS Econ.) |

| Occupation |

|

| Awards | List of honors and awards |

| Signature |  |

| Website | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Business and personal 45th President of the United States Tenure Impeachments Prosecutions Interactions involving Russia  |

||

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American media personality and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Born and raised in Queens, New York City, Trump attended Fordham University and the University of Pennsylvania, graduating with a bachelor's degree in 1968. He became the president of his father Fred Trump's real estate business in 1971 and renamed it The Trump Organization. Trump expanded the company's operations to building and renovating skyscrapers, hotels, casinos, and golf courses. He later started various side ventures, mostly by licensing his name. Trump and his businesses have been involved in more than 4,000 state and federal legal actions, including six bankruptcies. He owned the Miss Universe brand of beauty pageants from 1996 to 2015. From 2003 to 2015 he co-produced and hosted the reality television series The Apprentice.

He was elected as president of the United States after entering the 2016 presidential race as a Republican. Trump's political positions have been described as populist, protectionist, isolationist, and nationalist.

Personal life[edit]

Early life[edit]

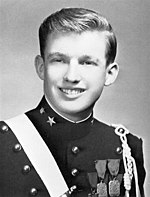

Donald John Trump was born on June 14, 1946, at Jamaica Hospital in the borough of Queens in New York City,[1][2] the fourth child of Fred Trump, a Bronx-born real estate developer whose parents were German immigrants, and Mary Anne MacLeod Trump, an immigrant from Scotland. Trump grew up with older siblings Maryanne, Fred Jr., and Elizabeth, and younger brother Robert in the Jamaica Estates neighborhood of Queens and attended the private Kew-Forest School from kindergarten through seventh grade.[3][4][5] At age 13, he was enrolled in the New York Military Academy, a private boarding school,[6] and in 1964, he enrolled at Fordham University. Two years later he transferred to the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, graduating in May 1968 with a B.S. in economics.[7][8] The New York Times reported in 1973 and 1976 that he had graduated first in his class at Wharton, but he had never made the school's honor roll.[9] In 2015, Trump's lawyer Michael Cohen threatened Fordham University and the New York Military Academy with legal action if they released Trump's academic records.[10] While in college, Trump obtained four student draft deferments.[11] In 1966, he was deemed fit for military service based upon a medical examination, and in July 1968 a local draft board classified him as eligible to serve.[12] In October 1968, he was classified 1-Y, a conditional medical deferment,[13] and in 1972, he was reclassified 4-F due to bone spurs, permanently disqualifying him from service.[14][15]

Family[edit]

In 1977, Trump married Czech model Ivana Zelníčková.[16] They have three children, Donald Jr. (born 1977), Ivanka (born 1981), and Eric (born 1984).[17] Ivana became a naturalized United States citizen in 1988.[18] The couple divorced in 1992, following Trump's affair with actress Marla Maples.[19] Maples and Trump married in 1993[20] and had one daughter, Tiffany (born 1993).[21] They were divorced in 1999,[22] and Tiffany was raised by Marla in California.[23] In 2005, Trump married Slovenian model Melania Knauss.[24] They have one son, Barron (born 2006).[25] Melania gained U.S. citizenship in 2006.[26]

Religious views[edit]

Trump went to Sunday school and was confirmed in 1959 at the First Presbyterian Church in Jamaica, Queens.[27][28] In the 1970s, his parents joined the Marble Collegiate Church in Manhattan, which belongs to the Reformed Church.[27][29] The pastor at Marble, Norman Vincent Peale,[27] ministered to the family until his death in 1993.[29] Trump has described Peale as a mentor.[30] In 2015, the church stated Trump "is not an active member".[28] In 2019, Trump appointed his personal pastor, televangelist Paula White, to the White House Office of Public Liaison.[31] In 2020, Trump said that he identified as a non-denominational Christian.[32]

Health[edit]

Trump says he has never drunk alcohol, smoked cigarettes, or used drugs.[33][34] He sleeps about four or five hours a night.[35][36] Trump has called golfing his "primary form of exercise" but usually does not walk the course.[37] He considers exercise a waste of energy, because he believes the body is "like a battery, with a finite amount of energy" which is depleted by exercise.[38]

In 2015, Harold Bornstein, who had been Trump's personal physician since 1980, wrote that Trump would "be the healthiest individual ever elected to the presidency" in a letter released by the Trump campaign.[39] In 2018, Bornstein said Trump had dictated the contents of the letter and that three agents of Trump had removed his medical records in February 2017 without authorization.[39][40]

Trump was hospitalized at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center for COVID-19 treatment on October 2, 2020, reportedly with a fever and difficulty breathing. It was revealed in 2021 that his condition had been much more serious. He had extremely low blood oxygen levels, a high fever, and lung infiltrates, indicating a severe case of the disease.[41] He was treated with the antiviral drug remdesevir, the steroid dexamethasone, and the unapproved experimental antibody REGN-COV2.[42] Trump returned to the White House on October 5, still struggling with the disease.[41]

Wealth[edit]

In 1982, Trump was listed on the initial Forbes list of wealthy individuals as having a share of his family's estimated $200 million net worth. His financial losses in the 1980s caused him to be dropped from the list between 1990 and 1995.[43] In its 2021 billionaires ranking, Forbes estimated Trump's net worth at $2.4 billion (1,299th in the world),[44] making him one of the richest politicians in American history and the first billionaire American president.[44] Forbes estimated that his net worth declined 31 percent and his ranking fell 138 spots between 2015 and 2018.[45] When he filed mandatory financial disclosure forms with the Federal Election Commission (FEC) in July 2015, Trump claimed a net worth of about $10 billion;[46] however, FEC figures cannot corroborate this estimate because they only show each of his largest buildings as being worth over $50 million, yielding total assets worth more than $1.4 billion and debt of more than $265 million.[47]

Journalist Jonathan Greenberg reported in 2018 that Trump, using the pseudonym "John Barron" and claiming to be a Trump Organization official, called him in 1984 to falsely assert that he owned "in excess of ninety percent" of the Trump family's business, to secure a higher ranking on the Forbes 400 list of wealthy Americans. Greenberg also wrote that Forbes had vastly overestimated Trump's wealth and wrongly included him on the Forbes 400 rankings of 1982, 1983, and 1984.[48]

Trump has often said he began his career with "a small loan of one million dollars" from his father, and that he had to pay it back with interest.[49] In October 2018, The New York Times reported that Trump "was a millionaire by age 8," borrowed at least $60 million from his father, largely failed to repay those loans, and had received $413 million (adjusted for inflation) from his father's business empire over his lifetime.[50][51] According to the report, Trump and his family committed tax fraud, which a lawyer for Trump denied. The tax department of New York said it is investigating.[52][53] Trump's investments underperformed the stock market and the New York property market.[54][55] Forbes estimated in October 2018 that the value of Trump's personal brand licensing business had declined by 88 percent since 2015, to $3 million.[56]

Trump's tax returns from 1985 to 1994 show net losses totaling $1.17 billion over the ten-year period, in contrast to his claims about his financial health and business abilities. The New York Times reported that "year after year, Mr. Trump appears to have lost more money than nearly any other individual American taxpayer" and that Trump's "core business losses in 1990 and 1991—more than $250 million each year—were more than double those of the nearest taxpayers in the I.R.S. information for those years." In 1995 his reported losses were $915.7 million.[57][58]

According to a September 2020 analysis by The New York Times of twenty years of data from Trump's tax returns, Trump had accumulated hundreds of millions in losses and deferred declaring $287 million in forgiven debt as taxable income.[59] According to the analysis, Trump's main sources of income were his share of revenue from The Apprentice and income from businesses in which he was a minority partner, while his majority-owned businesses were largely running at losses.[59] A significant portion of Trump's income was in tax credits due to his losses, which enables him to avoid paying income tax, or paying as little as $750, for several years.[59] Over the past decade, Trump has been balancing his businesses' losses by selling and taking out loans against assets, including a $100 million mortgage on Trump Tower (due in 2022) and the liquidation of over $200 million in stocks and bonds.[59] Trump has personally guaranteed $421 million in debt, most of which is due to be repaid by 2024. The tax records also showed Trump had unsuccessfully pursued business deals in China, including by developing a partnership with a major government-controlled company.[60]

Trump has a total of over $1 billion in debts, secured by his assets, according to a Forbes report in October 2020. $640 million or more was owed to various banks and trust organizations. Lenders include Deutsche Bank, UBS, and Bank of China. Approximately $450 million was owed to unknown creditors. The current value of Trump's assets exceeds his indebtedness, according to the report.[61]

Business career[edit]

Real estate[edit]

While a student at Wharton and after graduating in 1968, Trump worked at his father Fred's real estate company, Trump Management, which owned middle-class rental housing in New York City's outer boroughs.[62][63][64] In 1971, he became president of the company and began using The Trump Organization as an umbrella brand.[65] It was registered as a corporation in 1981.[66]

Manhattan developments[edit]

Trump attracted public attention in 1978 with the launch of his family's first Manhattan venture, the renovation of the derelict Commodore Hotel, adjacent to Grand Central Terminal. The financing was facilitated by a $400 million city property tax abatement arranged by Fred Trump,[67] who also joined Hyatt in guaranteeing $70 million in bank construction financing.[68][69] The hotel reopened in 1980 as the Grand Hyatt Hotel,[70] and that same year, Trump obtained rights to develop Trump Tower, a mixed-use skyscraper in Midtown Manhattan.[71] The building houses the headquarters of the Trump Organization and was Trump's primary residence until 2019.[72][73]

In 1988, Trump acquired the Plaza Hotel in Manhattan with a loan of $425 million from a consortium of banks. Two years later, the hotel filed for bankruptcy protection, and a reorganization plan was approved in 1992.[74] In 1995, Trump lost the hotel to Citibank and investors from Singapore and Saudi Arabia, who assumed $300 million of the debt.[75][76]

In 1996, Trump acquired the vacant 71-story skyscraper at 40 Wall Street. After an extensive renovation, the high-rise was renamed the Trump Building.[77] In the early 1990s, Trump won the right to develop a 70-acre (28 ha) tract in the Lincoln Square neighborhood near the Hudson River. Struggling with debt from other ventures in 1994, Trump sold most of his interest in the project to Asian investors, who were able to finance completion of the project, Riverside South.[78]

Palm Beach estate[edit]

In 1985, Trump acquired the Mar-a-Lago estate in Palm Beach, Florida.[79] Trump converted the estate into a private club with an initiation fee and annual dues and used a wing of the house as a private residence.[80] In 2019, Trump declared Mar-a-Lago his primary residence,[73] although under a 1993 agreement with the Town of Palm Beach, Trump may spend no more than three weeks per year there.[81]

Atlantic City casinos[edit]

In 1984, Trump opened Harrah's at Trump Plaza, a hotel and casino in Atlantic City, New Jersey. The project received financing from the Holiday Corporation, which also managed the operation. Gambling had been legalized there in 1977 to revitalize the once-popular seaside destination.[82] The property's poor financial results worsened tensions between Holiday and Trump, who paid Holiday $70 million in May 1986 to take sole control of the property.[83] Earlier, Trump had also acquired a partially completed building in Atlantic City from the Hilton Corporation for $320 million. Upon its completion in 1985, that hotel and casino were called Trump Castle. Trump's then-wife Ivana managed it until 1988.[84][85]

Trump acquired a third casino in Atlantic City, the Trump Taj Mahal, in 1988 in a highly leveraged transaction.[86] It was financed with $675 million in junk bonds and completed at a cost of $1.1 billion, opening in April 1990.[87][88][89] The project went bankrupt the following year,[88] and the reorganization left Trump with only half his initial ownership stake and required him to pledge personal guarantees of future performance.[90] Facing "enormous debt," he gave up control of his money-losing airline, Trump Shuttle, and sold his megayacht, the Trump Princess, which had been indefinitely docked in Atlantic City while leased to his casinos for use by wealthy gamblers.[91][92]

In 1995, Trump founded Trump Hotels & Casino Resorts (THCR), which assumed ownership of Trump Plaza, Trump Castle, and the Trump Casino in Gary, Indiana.[93] THCR purchased the Taj Mahal in 1996 and underwent successive bankruptcies in 2004, 2009, and 2014, leaving Trump with only ten percent ownership.[94] He remained chairman of THCR until 2009.[95]

Golf courses[edit]

The Trump Organization began acquiring and constructing golf courses in 1999.[96] It owned 16 golf courses and resorts worldwide and operated another two as of December 2016[update].[97]

From his inauguration until the end of 2019, Trump spent around one of every five days at one of his golf clubs.[98]

Branding and licensing[edit]

The Trump name has been licensed for various consumer products and services, including foodstuffs, apparel, adult learning courses, and home furnishings.[99][100] According to an analysis by The Washington Post, there are more than fifty licensing or management deals involving Trump's name, which have generated at least $59 million in yearly revenue for his companies.[101] By 2018, only two consumer goods companies continued to license his name.[100]

Legal affairs and bankruptcies[edit]

Fixer Roy Cohn served as Trump's lawyer and mentor for 13 years in the 1970s and 1980s.[102][103] According to Trump, Cohn sometimes waived fees due to their friendship.[63] In 1973, Cohn helped Trump countersue the United States government for $100 million over its charges that Trump's properties had racial discriminatory practices. Trump and Cohn lost that case when the countersuit was dismissed and the government's case went forward.[104] In 1975, an agreement was struck requiring Trump's properties to furnish the New York Urban League with a list of all apartment vacancies, every week for two years, among other things.[105] Cohn introduced political consultant Roger Stone to Trump, who enlisted Stone's services to deal with the federal government.[106]

As of April 2018[update], Trump and his businesses had been involved in more than 4,000 state and federal legal actions, according to a running tally by USA Today.[107]

While Trump has not filed for personal bankruptcy, his over-leveraged hotel and casino businesses in Atlantic City and New York filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection six times between 1991 and 2009.[108][109] They continued to operate while the banks restructured debt and reduced Trump's shares in the properties.[108][109]

During the 1980s, more than 70 banks had lent Trump $4 billion,[110] but in the aftermath of his corporate bankruptcies of the early 1990s, most major banks declined to lend to him, with only Deutsche Bank still willing to lend money.[111] The New York Times reported days after the storming of the United States Capitol that the bank had decided not to do business with Trump or his company in the future.[112]

In April 2019, the House Oversight Committee issued subpoenas seeking financial details from Trump's banks, Deutsche Bank and Capital One, and his accounting firm, Mazars USA. In response, Trump sued the banks, Mazars, and committee chairman Elijah Cummings to prevent the disclosures.[113][114] In May, DC District Court judge Amit Mehta ruled that Mazars must comply with the subpoena,[115] and judge Edgardo Ramos of the Southern District Court of New York ruled that the banks must also comply.[116][117] Trump's attorneys appealed the rulings,[118] arguing that Congress was attempting to usurp the "exercise of law-enforcement authority that the Constitution reserves to the executive branch."[119][120]

Side ventures[edit]

In September 1983, Trump purchased the New Jersey Generals, a team in the United States Football League. After the 1985 season, the league folded, largely due to Trump's strategy of moving games to a fall schedule (where they competed with the NFL for audience) and trying to force a merger with the NFL by bringing an antitrust suit against the organization.[121][122]

Trump's businesses have hosted several boxing matches at the Atlantic City Convention Hall adjacent to and promoted as taking place at the Trump Plaza in Atlantic City.[123][124] In 1989 and 1990, Trump lent his name to the Tour de Trump cycling stage race, which was an attempt to create an American equivalent of European races such as the Tour de France or the Giro d'Italia.[125]

In the late 1980s, Trump mimicked the actions of Wall Street's so-called corporate raiders. Trump began to purchase significant blocks of shares in various public companies, leading some observers to think he was engaged in the practice called greenmail, or feigning the intent to acquire the companies and then pressuring management to repurchase the buyer's stake at a premium. The New York Times found that Trump initially made millions of dollars in such stock transactions, but later "lost most, if not all, of those gains after investors stopped taking his takeover talk seriously."[57][126][127]

In 1988, Trump purchased the defunct Eastern Air Lines shuttle, with 21 planes and landing rights in New York City, Boston, and Washington, D.C. He financed the purchase with $380 million from 22 banks, rebranded the operation the Trump Shuttle, and operated it until 1992. Trump failed to earn a profit with the airline and sold it to USAir.[128]

In 1992, Trump, his siblings Maryanne, Elizabeth, and Robert, and his cousin John W. Walter, each with a 20 percent share, formed All County Building Supply & Maintenance Corp. The company had no offices and is alleged to have been a shell company for paying the vendors providing services and supplies for Trump's rental units and then billing those services and supplies to Trump Management with markups of 20–50 percent and more. The proceeds generated by the markups were shared by the owners.[51][129] The increased costs were used as justification to get state approval for increasing the rents of Trump's rent-stabilized units.[51]

From 1996 to 2015, Trump owned all or part of the Miss Universe pageants, including Miss USA and Miss Teen USA.[130][131] Due to disagreements with CBS about scheduling, he took both pageants to NBC in 2002.[132][133] In 2007, Trump received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for his work as producer of Miss Universe.[134] After NBC and Univision dropped the pageants from their broadcasting lineups in June 2015,[135] Trump bought NBC's share of the Miss Universe Organization and sold the entire company to the William Morris talent agency.[130]

Trump University[edit]

In 2004, Trump co-founded Trump University, a company that sold real estate training courses priced from $1,500 to $35,000.[136][137] After New York State authorities notified the company that its use of the word "university" violated state law, its name was changed to Trump Entrepreneur Initiative in 2010.[138]

In 2013, the State of New York filed a $40 million civil suit against Trump University, alleging that the company made false statements and defrauded consumers.[139][140] In addition, two class actions were filed in federal court against Trump and his companies. Internal documents revealed that employees were instructed to use a hard-sell approach, and former employees testified that Trump University had defrauded or lied to its students.[141][142][143] Shortly after he won the presidency, Trump agreed to pay a total of $25 million to settle the three cases.[144]

Foundation[edit]

The Donald J. Trump Foundation was a private foundation established in 1988.[145][146] In the foundation's final years its funds mostly came from donors other than Trump, who did not donate any personal funds to the charity from 2009 until 2014.[147] The foundation gave to health care and sports-related charities, as well as conservative groups.[148]

In 2016, The Washington Post reported that the charity had committed several potential legal and ethical violations, including alleged self-dealing and possible tax evasion.[149] Also in 2016, the New York State attorney general's office said the foundation appeared to be in violation of New York laws regarding charities and ordered it to immediately cease its fundraising activities in New York.[150][151] Trump's team announced in December 2016 that the foundation would be dissolved.[152]

In June 2018, the New York attorney general's office filed a civil suit against the foundation, Trump, and his adult children, seeking $2.8 million in restitution and additional penalties.[153][154] In December 2018, the foundation ceased operation and disbursed all its assets to other charities.[155] In November 2019, a New York state judge ordered Trump to pay $2 million to a group of charities for misusing the foundation's funds, in part to finance his presidential campaign.[156][157]

Media career[edit]

Books[edit]

Trump has written up to 19 books on business, financial, or political topics, though he has used ghostwriters to do this.[158] Trump's first book, The Art of the Deal (1987), was a New York Times Best Seller. While Trump was credited as co-author, the entire book was ghostwritten by Tony Schwartz.[159] According to The New Yorker, "The book expanded Trump's renown far beyond New York City, making him an emblem of the successful tycoon."[159] Trump has called the book his second favorite, after the Bible.[160]

Film and television[edit]

Trump made cameo appearances in eight films and television shows from 1985 to 2001.[161][162]

Trump had a sporadic relationship with the professional wrestling promotion WWE since the late 1980s.[163] He appeared at WrestleMania 23 in 2007 and was inducted into the celebrity wing of the WWE Hall of Fame in 2013.[164]

Starting in the 1990s, Trump was a guest about 24 times on the nationally syndicated Howard Stern Show.[165] He also had his own short-form talk radio program called Trumped! (one to two minutes on weekdays) from 2004 to 2008.[166][167] From 2011 until 2015, he was a weekly unpaid guest commentator on Fox & Friends.[168][169]

In 2003, Trump became the co-producer and host of The Apprentice, a reality show in which Trump played the role of a chief executive and contestants competed for a year of employment at the Trump Organization. Trump eliminated contestants with the catchphrase "You're fired."[170] He later co-hosted The Celebrity Apprentice, in which celebrities competed to win money for charities.[170] Trump, who had been a member since 1989, resigned from the Screen Actors Guild in February 2021 rather than face a disciplinary committee hearing for inciting the January 6, 2021 mob attack on the U.S. Capitol and for his "reckless campaign of misinformation aimed at discrediting and ultimately threatening the safety of journalists."[171] Two days later, the union permanently barred him from readmission.[172]

Pre-presidential political career[edit]

Trump's political party affiliation changed numerous times. He registered as a Republican in 1987, a member of the Independence Party, the New York state affiliate of the Reform Party, in 1999,[173] a Democrat in 2001, a Republican in 2009, unaffiliated in 2011, and a Republican in 2012.[174]

In 1987, Trump placed full-page advertisements in three major newspapers,[175] advocating peace in Central America, accelerated nuclear disarmament talks with the Soviet Union, and reduction of the federal budget deficit by making American allies pay "their fair share" for military defense.[176] He ruled out running for local office but not for the presidency.[175]

In 2000, Trump ran in the California and Michigan primaries for nomination as the Reform Party candidate for the 2000 United States presidential election but withdrew from the race in February 2000.[177][178][179] A July 1999 poll matching him against likely Republican nominee George W. Bush and likely Democratic nominee Al Gore showed Trump with seven percent support.[180]

In 2011, Trump speculated about running against President Barack Obama in the 2012 election, making his first speaking appearance at the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) in February 2011 and giving speeches in early primary states.[181][182] In May 2011, he announced he would not run,[181] and he endorsed Mitt Romney in February 2012.[183] Trump's presidential ambitions were generally not taken seriously at the time.[184]

2016 presidential campaign[edit]

Republican primaries[edit]

On June 16, 2015, Trump announced his candidacy for President of the United States.[185][186] His campaign was initially not taken seriously by political analysts, but he quickly rose to the top of opinion polls.[187]

On Super Tuesday, Trump received the most votes, and he remained the front-runner throughout the primaries.[188] After a landslide win in Indiana on May 3, 2016—which prompted the remaining candidates Ted Cruz and John Kasich to suspend their presidential campaigns—RNC chairman Reince Priebus declared Trump the presumptive Republican nominee.[189]

General election campaign[edit]

Hillary Clinton had a significant lead over Trump in national polls throughout most of 2016. In early July, her lead narrowed in national polling averages.[190][191]

On July 15, 2016, Trump announced his selection of Indiana governor Mike Pence as his vice presidential running mate.[192] Four days later, the two were officially nominated by the Republican Party at the Republican National Convention.[193]

Trump and Clinton faced off in three presidential debates in September and October 2016. Trump's refusal to say whether he would accept the result of the election drew attention, with some saying it undermined democracy.[194][195]

Political positions[edit]

Trump's campaign platform emphasized renegotiating U.S.–China relations and free trade agreements such as NAFTA and the Trans-Pacific Partnership, strongly enforcing immigration laws, and building a new wall along the U.S.–Mexico border. His other campaign positions included pursuing energy independence while opposing climate change regulations such as the Clean Power Plan and the Paris Agreement, modernizing and expediting services for veterans, repealing and replacing the Affordable Care Act, abolishing Common Core education standards, investing in infrastructure, simplifying the tax code while reducing taxes for all economic classes, and imposing tariffs on imports by companies that offshore jobs. During the campaign, he advocated a largely non-interventionist approach to foreign policy while increasing military spending, extreme vetting or banning immigrants from Muslim-majority countries[196] to pre-empt domestic Islamic terrorism, and aggressive military action against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. He described NATO as "obsolete".[197][198]

Trump's political positions and rhetoric were right-wing populist.[199][200][201] Politico has described his positions as "eclectic, improvisational and often contradictory,"[202] while NBC News counted "141 distinct shifts on 23 major issues" during his campaign.[203]

Campaign rhetoric[edit]

Trump said he disdained political correctness and frequently made claims of media bias.[204][205][206] His fame and provocative statements earned him an unprecedented amount of free media coverage, elevating his standing in the Republican primaries.[207]

Trump made a record number of false statements compared to other candidates;[208][209][210] the press reported on his campaign lies and falsehoods, with the Los Angeles Times saying, "Never in modern presidential politics has a major candidate made false statements as routinely as Trump has."[211] His campaign statements were often opaque or suggestive.[212]

Trump adopted the phrase "truthful hyperbole," coined by his ghostwriter Tony Schwartz, to describe his public speaking style.[213][214]

Support from the far-right[edit]

According to Michael Barkun, the Trump campaign was remarkable for bringing fringe ideas, beliefs, and organizations into the mainstream.[215] During his presidential campaign, Trump was accused of pandering to white supremacists.[216] He retweeted racist Twitter accounts,[217] and repeatedly refused to condemn David Duke, the Ku Klux Klan or white supremacists.[218] Duke enthusiastically supported Trump and said he and like-minded people voted for Trump because of his promises to "take our country back".[219][220] After repeated questioning by reporters, Trump said he disavowed Duke and the Klan.[221]

The alt-right movement coalesced around and enthusiastically supported Trump's candidacy,[222][223] due in part to its opposition to multiculturalism and immigration.[224][225][226]

In August 2016, he appointed Steve Bannon, the executive chairman of Breitbart News—described by Bannon as "the platform for the alt-right"—as his campaign CEO.[227] After the election, Trump condemned supporters who celebrated his victory with Nazi salutes.[228][229]

Financial disclosures[edit]

As a candidate, Trump's FEC-required reports listed assets above $1.4 billion[47][230] and outstanding debts of at least $315 million.[97]

Trump did not release his tax returns, contrary to the practice of every major candidate since 1976 and his promises in 2014 and 2015 to do so if he ran for office.[231][232] He said his tax returns were being audited, and his lawyers had advised him against releasing them.[233] After a lengthy court battle to block release of his tax returns and other records to the Manhattan district attorney for a criminal investigation, including two appeals by Trump to the United States Supreme Court, in February 2021 the high court allowed the records to be released to the prosecutor for review by a grand jury.[234][235]

In October 2016, portions of Trump's state filings for 1995 were leaked to a reporter from The New York Times. They show that Trump had declared a loss of $916 million that year, which could have let him avoid taxes for up to 18 years.[236] In March 2017, the first two pages of Trump's 2005 federal income tax returns were leaked to MSNBC. The document states that Trump had a gross adjusted income of $150 million and paid $38 million in federal taxes. The White House confirmed the authenticity of the documents.[237][238]

Election to the presidency[edit]

On November 8, 2016, Trump received 306 pledged electoral votes versus 232 for Clinton. The official counts were 304 and 227 respectively, after defections on both sides.[239] Trump received nearly 2.9 million fewer popular votes than Clinton, which made him the fifth person to be elected president while losing the popular vote.[240]

Trump's victory was a political upset.[241] Polls had consistently shown Clinton with a nationwide—though diminishing—lead, as well as an advantage in most of the competitive states. Trump's support had been modestly underestimated, while Clinton's had been overestimated.[242]

Trump won 30 states; included were Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, which had been part of what was considered a blue wall of Democratic strongholds since the 1990s. Clinton won 20 states and the District of Columbia. Trump's victory marked the return of an undivided Republican government—a Republican White House combined with Republican control of both chambers of Congress.[243]

Trump was the oldest person to take office as president at the time of his inauguration.[244] He is also the first president who did not serve in the military or hold any government office prior to becoming president.[245]

Protests[edit]

Trump's election victory sparked numerous protests.[246][247] On the day after Trump's inauguration, an estimated 2.6 million people worldwide, including an estimated half million in Washington, D.C., protested against Trump in the Women's Marches.[248] Marches against his travel ban began across the country on January 29, 2017, just nine days after his inauguration.[249]

Presidency (2017–2021)[edit]

Trump's political positions have been described as populist, protectionist, isolationist, and nationalist. He entered the 2016 presidential race as a Republican and was elected in an upset victory over Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton while losing the popular vote.[a] He was the first U.S. president without prior military or government service. His election and policies sparked numerous protests. Trump made many false and misleading statements during his campaigns and presidency, to a degree unprecedented in American politics. Many of his comments and actions have been characterized as racially charged or racist.

Trump ordered a travel ban on citizens from several Muslim-majority countries, citing security concerns; after legal challenges, the Supreme Court upheld the policy's third revision. He enacted the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 which cut taxes for individuals and businesses and rescinded the individual health insurance mandate penalty of the Affordable Care Act. He appointed Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court as well as more than 200 federal judges. In foreign policy, Trump pursued an America First agenda: he renegotiated the North American Free Trade Agreement as the U.S.–Mexico–Canada Agreement and withdrew the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade negotiations, the Paris Agreement on climate change and the Iran nuclear deal. He imposed import tariffs that triggered a trade war with China and met three times with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, but negotiations on denuclearization eventually broke down. Trump reacted slowly to the COVID-19 pandemic, ignored or contradicted many recommendations from health officials in his messaging, and promoted misinformation about unproven treatments and the availability of testing.

Russia interfered in the 2016 election to help Trump's election chances, but the special counsel investigation of that interference led by Robert Mueller did not find sufficient evidence to establish criminal conspiracy or coordination of the Trump campaign with Russia.[b] Mueller also investigated Trump for obstruction of justice and neither indicted nor exonerated him. After Trump pressured Ukraine to investigate his political rival Joe Biden, the House of Representatives impeached him for abuse of power and obstruction of Congress on December 18, 2019. The Senate acquitted him of both charges on February 5, 2020.

Trump lost the 2020 presidential election to Biden, but refused to concede defeat. He attempted to overturn the results by making false claims of electoral fraud, pressuring government officials, mounting scores of unsuccessful legal challenges and obstructing the presidential transition. On January 6, 2021, Trump urged his supporters to march to the Capitol, which hundreds stormed, interrupting the electoral vote count. The House impeached Trump for incitement of insurrection on January 13, making him the only federal officeholder in American history to be impeached twice. The Senate acquitted Trump for the second time on February 13.

Post-presidency[edit]

After his term ended, Trump went to live at his Mar-a-Lago club in Palm Beach, Florida.[250][81] As provided for by the Former Presidents Act,[251] he established an office there to handle his post-presidential activities.[251][252]

Since leaving the presidency, Trump has been the subject of several probes into both his business dealings and his actions during the presidency. In February 2021, the District Attorney for Fulton County, Georgia, announced a criminal probe into Trump's phone calls to Brad Raffensperger.[253] Separately, the New York State Attorney General's Office is conducting a civil and criminal investigation into Trump's business activities. The criminal investigation is in conjunction with the Manhattan District Attorney's Office.[254] By May 2021, a special grand jury was considering indictments.[255][256]

Trump's false claims concerning the 2020 election were commonly referred to as the "big lie" by his critics. In May 2020, Trump and his supporters co-opted the term, and the Republican party had come to use the false narrative as justification to impose new voting restrictions in its favor. [257][258][259][260]

In June 2021, multiple national publications reported that Trump had told several people he could be reinstated as president in August.[261][262] On June 6, 2021, Trump resumed his campaign-style rallies with an 85-minute speech at the annual North Carolina Republican Party convention.[261][263] On June 27, he held his first public rally since his January 6 rally before the riot at the Capitol.[264]

Public profile[edit]

Approval ratings[edit]

For much of his term through September 2020, Trump's approval and disapproval ratings were unusually stable, reaching a high of 49 percent and a low of 35 percent.[265][266] He completed his term with a record-low approval rating of between 29 percent to 34 percent (the lowest of any president since modern scientific polling began); his average approval rating throughout his term was a record-low 41 percent.[267][268] Trump's approval ratings showed a record partisan gap: over the course of his presidency, Trump's approval rating among Republicans was 88 percent and his approval rating among Democrats was 7 percent.[268]

In Gallup's annual poll asking Americans to name the man they admire the most, Trump placed second to Obama in 2017 and 2018, tied with Obama for most admired man in 2019, and was named most admired in 2020.[269][270] Since Gallup started conducting the poll in 1948,[271] Trump is the first elected president not to be named most admired in his first year in office.[271]

A Gallup poll in 134 countries comparing the approval ratings of U.S. leadership between the years 2016 and 2017 found that Trump led Obama in job approval in only 29, most of them non-democracies,[272] with approval of US leadership plummeting among US allies and G7 countries. Overall ratings were similar to those in the last two years of the George W. Bush presidency.[273] By mid-2020, only 16% of international respondents expressed confidence in Trump according to a 13-nation Pew Research poll, a confidence score lower than those historically accorded to Russia's Vladimir Putin and China's Xi Jinping.[274]

Social media[edit]

Trump's social media presence attracted attention worldwide since he joined Twitter in 2009. He frequently tweeted during the 2016 election campaign and as president, until his ban in the final days of his term.[275] Over twelve years, Trump posted around 57,000 tweets.[276] Trump frequently used Twitter as a direct means of communication with the public, sidelining the press.[276] A White House press secretary said early in his presidency that Trump's tweets were official presidential statements, used for announcing policies and personnel changes.[277][278][279]

Trump's tweets often contained falsehoods, eventually causing Twitter to tag some of them with fact-checking warnings beginning in May 2020.[280] Trump responded by threatening to "strongly regulate" or "close down" social media platforms.[281] In the days after the storming of the United States Capitol, Trump was banned from Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and other platforms.[282] Twitter blocked attempts by Trump and his staff to circumvent the ban through the use of others' accounts.[283] The loss of Trump's social media megaphone, including his 88.7 million Twitter followers, diminished his ability to shape events,[284][285] and prompted a dramatic decrease in the volume of misinformation shared on Twitter.[286] In May 2021, an advisory group to Facebook evaluated that site's indefinite ban of Trump and concluded that it had been justified at the time but should be re-evaluated in six months.[287] In June 2021, Facebook suspended the account for two years.[288]

False statements[edit]

As a candidate and as president, Trump frequently made false statements in public speeches and remarks[292][208] to an extent unprecedented in American politics.[293][294][214] His falsehoods became a distinctive part of his political identity.[294]

Trump's false and misleading statements were documented by fact-checkers, including at the Washington Post, which tallied a total of 30,573 false or misleading statements made by Trump over his four-year term.[289] Trump's falsehoods increased in frequency over time, rising from about 6 false or misleading claims per day in his first year as president to 16 per day in his second year to 22 per day in his third year to 39 per day in his final year.[295] He reached 10,000 false or misleading claims 27 months into his term; 20,000 false or misleading claims 14 months later, and 30,000 false or misleading claims five months later.[295]

Some of Trump's falsehoods were inconsequential, such as his claims of a large crowd size during his inauguration.[296][297] Others had more far-reaching effects, such as Trump's promotion of unproven antimalarial drugs as a treatment for COVID‑19 in a press conference and on Twitter in March 2020.[298][299] The claims had consequences worldwide, such as a shortage of these drugs in the United States and panic-buying in Africa and South Asia.[300][301] Other misinformation, such as misattributing a rise in crime in England and Wales to the "spread of radical Islamic terror," served Trump's domestic political purposes.[302] As a matter of principle, Trump does not apologize for his falsehoods.[303]

Despite the frequency of Trump's falsehoods, the media rarely referred to them as lies.[304][305] Nevertheless, in August 2018 The Washington Post declared for the first time that some of Trump's misstatements (statements concerning hush money paid to Stormy Daniels and Playboy model Karen McDougal) were lies.[306][305]

In 2020, Trump was a significant source of disinformation on national voting practices and the COVID-19 pandemic.[307] Trump's attacks on mail-in ballots and other election practices served to weaken public faith in the integrity of the 2020 presidential election,[308][309] while his disinformation about the pandemic delayed and weakened the national response to it.[307][310][311]

Some view the nature and frequency of Trump's falsehoods as having profound and corrosive consequences on democracy.[312] James Pfiffner, professor of policy and government at George Mason University, wrote in 2019 that Trump lies differently from previous presidents, because he offers "egregious false statements that are demonstrably contrary to well-known facts"; these lies are the "most important" of all Trump lies. By calling facts into question, people will be unable to properly evaluate their government, with beliefs or policy irrationally settled by "political power"; this erodes liberal democracy, wrote Pfiffner.[313]

Promotion of conspiracy theories[edit]

Before and throughout his presidency, Trump has promoted numerous conspiracy theories, including Obama birtherism, the Clinton Body Count theory, QAnon, and alleged Ukrainian interference in U.S. elections.[314] In October 2020, Trump retweeted a QAnon follower who asserted that Osama bin Laden was still alive, a body double had been killed in his place, and that "Biden and Obama may have had SEAL Team Six killed."[315]

During and since the 2020 United States presidential election, Trump has promoted various conspiracy theories for his defeat including the "dead voter" conspiracy theory,[316] and without providing any evidence he has created other conspiracy theories such as that "some states allowed voters to turn in ballots after Election Day; that vote-counting machines were rigged to favor Mr Biden; and even that the FBI, the Justice Department and the federal court system were complicit in an attempt to cover up election fraud."[317]

Relationship with the press[edit]

Throughout his career, Trump has sought media attention, with a "love–hate" relationship with the press.[318] Trump began promoting himself in the press in the 1970s.[319] Fox News anchor Bret Baier and former House speaker Paul Ryan have characterized Trump as a "troll" who makes controversial statements to see people's "heads explode."[320][321]

In the 2016 campaign, Trump benefited from a record amount of free media coverage, elevating his standing in the Republican primaries.[207] New York Times writer Amy Chozick wrote in 2018 that Trump's media dominance, which enthralls the public and creates "can't miss" reality television-type coverage, was politically beneficial for him.[322]

As a candidate and as president, Trump frequently accused the press of bias, calling it the "fake news media" and "the enemy of the people."[323] In 2018, journalist Lesley Stahl recounted Trump's saying he intentionally demeaned and discredited the media "so when you write negative stories about me no one will believe you."[324]

As president, Trump privately and publicly mused about revoking the press credentials of journalists he viewed as critical.[325] His administration moved to revoke the press passes of two White House reporters, which were restored by the courts.[326] In 2019, a member of the foreign press reported many of the same concerns as those of media in the U.S., expressing concern that a normalization process by reporters and media results in an inaccurate characterization of Trump.[327] The Trump White House held about a hundred formal press briefings in 2017, declining by half during 2018 and to two in 2019.[326]

As president, Trump deployed the legal system to intimidate the press.[328] In early 2020, the Trump campaign sued The New York Times, The Washington Post, and CNN for alleged defamation in opinion pieces about Russian election interference.[329][330] Legal experts said that the lawsuits lacked merit and were not likely to succeed.[328][331] By March 2021, the lawsuits against The New York Times and CNN had been dismissed.[332][333]

Racial views[edit]

Many of Trump's comments and actions have been considered racist.[334] He has repeatedly denied this, asserting: "I am the least racist person there is anywhere in the world."[335] In national polling, about half of Americans say that Trump is racist; a greater proportion believe that he has emboldened racists.[336][337][338] Several studies and surveys have found that racist attitudes fueled Trump's political ascendance and have been more important than economic factors in determining the allegiance of Trump voters.[339][340] Racist and Islamophobic attitudes are a strong indicator of support for Trump.[341]

In 1975, he settled a 1973 Department of Justice lawsuit that alleged housing discrimination against black renters.[63] He has also been accused of racism for insisting a group of black and Latino teenagers were guilty of raping a white woman in the 1989 Central Park jogger case, even after they were exonerated by DNA evidence in 2002. As of 2019, he maintained this position.[342]

Trump relaunched his political career in 2011 as a leading proponent of "birther" conspiracy theories alleging that Barack Obama, the first black U.S. president, was not born in the United States.[343][344] In April 2011, Trump claimed credit for pressuring the White House to publish the "long-form" birth certificate, which he considered fraudulent, and later saying this made him "very popular".[345][346] In September 2016, amid pressure, he acknowledged that Obama was born in the U.S. and falsely claimed the rumors had been started by Hillary Clinton during her 2008 presidential campaign.[347] In 2017, he reportedly still expressed birther views in private.[348]

According to an analysis in Political Science Quarterly, Trump made "explicitly racist appeals to whites" during his 2016 presidential campaign.[349] In particular, his campaign launch speech drew widespread criticism for claiming Mexican immigrants were "bringing drugs, they're bringing crime, they're rapists."[350][351] His later comments about a Mexican-American judge presiding over a civil suit regarding Trump University were also criticized as racist.[352]

Trump's comment on the 2017 far-right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia—that there were "very fine people on both sides"—was widely criticized as implying a moral equivalence between the white supremacist demonstrators and the counter-protesters at the rally.[353][354][355]

In a January 2018 Oval Office meeting to discuss immigration legislation, Trump reportedly referred to El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, and African nations as "shithole countries."[356] His remarks were condemned as racist.[357][358]

In July 2019, Trump tweeted that four Democratic congresswomen—all minorities, three of whom are native-born Americans—should "go back" to the countries they "came from."[359] Two days later the House of Representatives voted 240–187, mostly along party lines, to condemn his "racist comments."[360] White nationalist publications and social media sites praised his remarks, which continued over the following days.[361] Trump continued to make similar remarks during his 2020 campaign.[362]

Misogyny and allegations of sexual misconduct[edit]

Trump has a history of insulting and belittling women when speaking to media and in tweet. He made lewd comments, demeaned women's looks, and called them names like 'dog', 'crazed, crying lowlife', 'face of a pig', or 'horseface'.[363][364][365]

In October 2016, two days before the second presidential debate, a 2005 "hot mic" recording surfaced in which Trump was heard bragging about kissing and groping women without their consent, saying "when you're a star, they let you do it, you can do anything... grab 'em by the pussy."[366] The incident's widespread media exposure led to Trump's first public apology during the campaign[367] and caused outrage across the political spectrum.[368]

At least twenty-six women have publicly accused Trump of sexual misconduct as of September 2020[update], including his then-wife Ivana. There were allegations of rape, violence, being kissed and groped without consent, looking under women's skirts, and walking in on naked women.[369][370][371] In 2016, he denied all accusations, calling them "false smears," and alleged there was a conspiracy against him.[372]

Allegations of inciting violence[edit]

Research suggests Trump's rhetoric caused an increased incidence of hate crimes.[373][374][375] During the 2016 campaign, he urged or praised physical attacks against protesters or reporters.[376][377] Since then, some defendants prosecuted for hate crimes or violent acts cited Trump's rhetoric in arguing that they were not culpable or should receive a lighter sentence.[378] In May 2020, a nationwide review by ABC News identified at least 54 criminal cases from August 2015 to April 2020 in which Trump was invoked in direct connection with violence or threats of violence by mostly white men against mostly members of minority groups.[379] On January 13, 2021, the House of Representatives impeached Trump for incitement of insurrection for his actions prior to the storming of the U.S. Capitol by a violent mob of his supporters[380] who acted in his name.[381]

Popular culture[edit]

Trump has been the subject of parody, comedy, and caricature. He has been parodied regularly on Saturday Night Live by Phil Hartman, Darrell Hammond, and Alec Baldwin and in South Park as Mr. Garrison. The Simpsons episode "Bart to the Future"—written during his 2000 campaign for the Reform Party—anticipated a Trump presidency. Trump's wealth and lifestyle had been a fixture of hip-hop lyrics since the 1980s; he was named in hundreds of songs, most often with a positive tone.[382] Mentions of Trump in hip-hop largely turned negative and pejorative after he ran for office in 2015.[382]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Presidential elections in the United States are decided by the Electoral College. Each state names a number of electors equal to its representation in Congress and (in most states) all delegates vote for the winner of the local state vote.

- ^ Mueller, Robert (March 2019). "Report on the Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election". I. p. 2. "In connection with that analysis, we addressed the factual question whether members of the Trump Campaign 'coordinat[ed]'—a term that appears in the appointment order—with Russian election interference activities. Like collusion, 'coordination' does not have a settled definition in federal criminal law. We understood coordination to require an agreement—tacit or express—between the Trump Campaign and the Russian government on election interference. That requires more than the two parties taking actions that were informed by or responsive to the other's actions or interests. We applied the term coordination in that sense when stating in the report that the investigation did not establish that the Trump campaign coordinated with the Russian government in its election interference activities."

References[edit]

- ^ "Certificate of Birth". Department of Health – City of New York – Bureau of Records and Statistics. Archived from the original on May 12, 2016. Retrieved October 23, 2018 – via ABC News.

- ^ "Certificate of Birth: Donald John Trump" (PDF). Jamaica Hospital Medical Center. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- ^ "Trump's parents and siblings: What do we know of them?". BBC News. October 3, 2018. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Kranish & Fisher 2017, p. 33.

- ^ Horowitz, Jason (September 22, 2015). "Donald Trump's Old Queens Neighborhood Contrasts With the Diverse Area Around It". The New York Times. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ Kranish & Fisher 2017, p. 38.

- ^ "Two Hundred and Twelfth Commencement for the Conferring of Degrees" (PDF). University of Pennsylvania. May 20, 1968. pp. 19–21. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 19, 2016.

- ^ Viser, Matt (August 28, 2015). "Even in college, Donald Trump was brash". The Boston Globe. Retrieved May 28, 2018.

- ^ Selk, Avi (May 20, 2018). "It's the 50th anniversary of the day Trump left college and (briefly) faced the draft". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- ^ Ashford, Grace (February 27, 2019). "Michael Cohen Says Trump Told Him to Threaten Schools Not to Release Grades". The New York Times. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- ^ Montopoli, Brian (April 29, 2011). "Donald Trump avoided Vietnam with deferments, records show". CBS News. Retrieved July 17, 2015.

- ^ "Donald John Trump's Selective Service Draft Card and Selective Service Classification Ledger". National Archives. August 15, 2016. Retrieved September 23, 2019. – via Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)

- ^ Whitlock, Craig (July 21, 2015). "Questions linger about Trump's draft deferments during Vietnam War". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 2, 2017.

- ^ Eder, Steve; Philipps, Dave (August 1, 2016). "Donald Trump's Draft Deferments: Four for College, One for Bad Feet". The New York Times. Retrieved August 2, 2016.

- ^ Emery, David (August 2, 2016). "Donald Trump's Draft Deferments". Snopes.com. Retrieved October 16, 2018.

- ^ Blair 2015b, p. 300.

- ^ "Lara and Eric Trump welcome second child". NBC Montana. August 20, 2019. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ "Ivana Trump becomes U.S. citizen". The Lewiston Journal. Associated Press. May 27, 1988. Retrieved August 21, 2015 – via Google News.

- ^ "Ivana Trump to write memoir about raising US president's children". The Guardian. Associated Press. March 16, 2017. Retrieved May 6, 2017.

- ^ Capuzzo, Mike (December 21, 1993). "Marla Finally Becomes Mrs. Trump It Was 'Paparazzi' Aplenty And Glitz Galore As The Couple Pledged Their Troth". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on January 19, 2016. Retrieved June 20, 2019.

- ^ Graham, Ruth (July 20, 2016). "Tiffany Trump's Sad, Vague Tribute to Her Distant Father". Slate. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- ^ Baylis, Sheila Cosgrove (August 7, 2013). "Marla Maples Still Loves Donald Trump". People. Retrieved May 6, 2017.

- ^ Stanley, Alessandra (October 1, 2016). "The Other Trump". The New York Times. Retrieved May 6, 2017.

- ^ Brown, Tina (January 27, 2005). "Donald Trump, Settling Down". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- ^ "Donald Trump Fast Facts". CNN. March 7, 2014. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ^ Gunter, Joel (March 2, 2018). "What is the Einstein visa? And how did Melania Trump get one?". BBC News. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- ^ a b c Barron, James (September 5, 2016). "Overlooked Influences on Donald Trump: A Famous Minister and His Church". The New York Times. Retrieved October 13, 2016.

- ^ a b Scott, Eugene (August 28, 2015). "Church says Donald Trump is not an 'active member'". CNN. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ a b Schwartzman, Paul (January 21, 2016). "How Trump got religion – and why his legendary minister's son now rejects him". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ Kranish & Fisher 2017, p. 81.

- ^ Peters, Jeremy W.; Haberman, Maggie (October 31, 2019). "Paula White, Trump's Personal Pastor, Joins the White House". The New York Times.

- ^ Jenkins, Jack; Mwaura, Maina (October 23, 2020). "Exclusive: Trump, confirmed a Presbyterian, now identifies as 'non-denominational Christian'". Religion News Service.

- ^ Nagourney, Adam (October 30, 2020). "In Trump and Biden, a Choice of Teetotalers for President". The New York Times. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- ^ Parker, Ashley; Rucker, Philip (October 2, 2018). "Kavanaugh likes beer – but Trump is a teetotaler: 'He doesn't like drinkers.'". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- ^ Dangerfield, Katie (January 17, 2018). "Donald Trump sleeps 4-5 hours each night; he's not the only famous 'short sleeper'". Global News. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- ^ Almond, Douglas; Du, Xinming (December 2020). "Later bedtimes predict President Trump's performance". Economics Letters. 197: 109590. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2020.109590. PMC 7518119. PMID 33012904.

- ^ "Donald Trump says he gets most of his exercise from golf, then uses cart at Turnberry". Golf News Net. July 14, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ Rettner, Rachael (May 14, 2017). "Trump thinks that exercising too much uses up the body's 'finite' energy". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b Marquardt, Alex; Crook, Lawrence III (May 1, 2018). "Bornstein claims Trump dictated the glowing health letter". CNN. Retrieved May 20, 2018.

- ^ Schecter, Anna (May 1, 2018). "Trump doctor Harold Bornstein says bodyguard, lawyer 'raided' his office, took medical files". NBC News. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ^ a b Weiland, Noah; Haberman, Maggie; Mazzetti, Mark; Karni, Annie (February 11, 2021). "Trump Was Sicker Than Acknowledged With Covid-19". The New York Times. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ Thomas, Katie; Kolata, Gina (October 5, 2020). "President Trump Received Experimental Antibody Treatment". The New York Times. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ O'Brien, Timothy L. (October 23, 2005). "What's He Really Worth?". The New York Times. Retrieved February 25, 2016.

- ^ a b "#1001 Donald Trump". Forbes. 2020. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- ^ Walsh, John (October 3, 2018). "Trump has fallen 138 spots on Forbes' wealthiest-Americans list, his net worth down over $1 billion, since he announced his presidential bid in 2015". Business Insider. Retrieved October 3, 2018.

- ^ Lewandowski, Corey R.; Hicks, Hope (July 15, 2015). "Donald J. Trump Files Personal Financial Disclosure Statement With Federal Election Commission" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 9, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ^ a b Horwitz, Jeff; Braun, Stephen (July 22, 2015). "Donald Trump wealth details released by federal regulators". Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on August 1, 2015. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- ^ Greenberg, Jonathan (April 20, 2018). "Trump lied to me about his wealth to get onto the Forbes 400. Here are the tapes". The Washington Post.

- ^ Stump, Scott (October 26, 2015). "Donald Trump: My dad gave me 'a small loan' of $1 million to get started". CNBC. Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- ^ Barstow, David; Craig, Susanne; Buettner, Russ (October 2, 2018). "11 Takeaways From The Times's Investigation into Trump's Wealth". The New York Times. Retrieved October 3, 2018.

- ^ a b c Barstow, David; Craig, Susanne; Buettner, Russ (October 2, 2018). "Trump Engaged in Suspect Tax Schemes as He Reaped Riches From His Father". The New York Times. Retrieved October 2, 2018.

- ^ Campbell, Jon; Spector, Joseph (October 3, 2018). "New York could levy hefty penalties if Trump tax fraud is proven". USA Today. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- ^ Woodward, Calvin; Pace, Julie (December 16, 2018). "Scope of investigations into Trump has shaped his presidency". AP News. Retrieved December 19, 2018.

- ^ "From the Tower to the White House". The Economist. February 20, 2016. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

Mr Trump's performance has been mediocre compared with the stockmarket and property in New York.

- ^ Swanson, Ana (February 29, 2016). "The myth and the reality of Donald Trump's business empire". The Washington Post.

- ^ Breuninger, Kevin (October 2, 2018). "Trump tumbles down the Forbes 400 as his net worth takes major hit". CNBC. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- ^ a b Buettner, Russ; Craig, Susanne (May 8, 2019). "Decade in the Red: Trump Tax Figures Show Over $1 Billion in Business Losses". The New York Times. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- ^ Friedersdorf, Conor (May 8, 2019). "The Secret That Was Hiding in Trump's Taxes". The Atlantic. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Buettner, Russ; Craig, Susanne; McIntire, Mike (September 27, 2020). "Trump's Taxes Show Chronic Losses and Years of Income Tax Avoidance". The New York Times. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ "Report: Tax records show Trump tried to land China projects". AP News. October 21, 2020.

- ^ Alexander, Dan (October 16, 2020). "Donald Trump Has at Least $1 Billion in Debt, More Than Twice The Amount He Suggested". Forbes. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- ^ Ehrenfreund, Max (September 3, 2015). "The real reason Donald Trump is so rich". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ a b c Mahler, Jonathan; Eder, Steve (August 27, 2016). "'No Vacancies' for Blacks: How Donald Trump Got His Start, and Was First Accused of Bias". The New York Times. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- ^ Trump 2020, p. 89.

- ^ Blair 2015b, p. 250.

- ^ "Trump Organization Inc/The". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- ^ Rich, Frank (April 29, 2018). "The Original Donald Trump". New York. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- ^ Kessler, Glenn (March 3, 2016). "Trump's false claim he built his empire with a 'small loan' from his father". The Washington Post.

- ^ Kranish & Fisher 2017, p. 84.

- ^ Wooten 2009, pp. 32–35.

- ^ Geist, William (April 8, 1984). "The Expanding Empire of Donald Trump". The New York Times.

- ^ Burns, Alexander (December 9, 2016). "Donald Trump Loves New York. But It Doesn't Love Him Back". The New York Times. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- ^ a b Haberman, Maggie (October 31, 2019). "Trump, Lifelong New Yorker, Declares Himself a Resident of Florida". The New York Times. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ "Trump's Plaza Hotel bankruptcy plan approved". The New York Times. Reuters. December 12, 1992. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ Stout, David; Gilpin, Kenneth (April 12, 1995). "Trump Is Selling Plaza Hotel To Saudi and Asian Investors". The New York Times. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ Satow, Julie (May 23, 2019). "That Time Trump Sold the Plaza Hotel at an $83 Million Loss". Bloomberg News. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ Wooten 2009, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Bagli, Charles V. (June 1, 2005). "Trump Group Selling West Side Parcel for $1.8 billion". The New York Times. Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- ^ Peterson-Withorn, Chase (April 23, 2018). "Donald Trump Has Gained More Than $100 Million On Mar-a-Lago". Forbes. Retrieved July 4, 2018.

- ^ Dangremond, Sam (December 22, 2017). "A History of Mar-a-Lago, Donald Trump's American Castle". Town & Country. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ a b "Florida town conducting legal review of Trump's residency at Mar-a-Lago". CNN. January 29, 2021.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ Wooten 2009, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Kranish & Fisher 2017, p. 128.

- ^ Wooten 2009, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Kranish & Fisher 2017, p. 137.

- ^ Cuff, Daniel (December 18, 1988). "Seven Acquisitive Executives Who Made Business News in 1988: Donald Trump–Trump Organization; The Artist of the Deal Turns Sour into Sweet". The New York Times. Retrieved May 27, 2011.

- ^ Glynn, Lenny (April 8, 1990). "Trump's Taj – Open at Last, With a Scary Appetite". The New York Times. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ^ a b "Trump reaches agreement with bondholders on Taj Mahal". United Press International. April 9, 1991. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ^ Kranish & Fisher 2017, p. 135.

- ^ "Taj Mahal is out of Bankruptcy". The New York Times. October 5, 1991. Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- ^ Hylton, Richard (May 11, 1990). "Trump Is Reportedly Selling Yacht". The New York Times. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ Kranish & Fisher 2017, pp. 132–133.

- ^ Norris, Floyd (June 7, 1995). "Trump Plaza casino stock trades today on Big Board". The New York Times. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- ^ McQuade, Dan (August 16, 2015). "The Truth About the Rise and Fall of Donald Trump's Atlantic City Empire". Philadelphia. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ^ Tully, Shawn (March 10, 2016). "How Donald Trump Made Millions Off His Biggest Business Failure". Fortune. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ^ Garcia, Ahiza (December 29, 2016). "Trump's 17 golf courses teed up: Everything you need to know". CNN Money. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ a b Alesci, Cristina; Frankel, Laurie; Sahadi, Jeanne (May 19, 2016). "A peek at Donald Trump's finances". CNN. Retrieved May 20, 2016.

- ^ Klein, Betsy (December 31, 2019). "Trump spent 1 of every 5 days in 2019 at a golf club". CNN. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

- ^ Lee, Michelle Ye Hee (August 26, 2016). "How many Trump products were made overseas? Here's the complete list". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ a b Anthony, Zane; Sanders, Kathryn; Fahrenthold, David A. (April 13, 2018). "Whatever happened to Trump neckties? They're over. So is most of Trump's merchandising empire". The Washington Post.

- ^ Williams, Aaron; Narayanswamy, Anu (January 25, 2017). "How Trump has made millions by selling his name". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- ^ Hornaday, Ann (September 24, 2019). "A portrait of an infamous fixer – and his most famous pupil – in 'Where's My Roy Cohn?'". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ Mahler, Jonathan; Flegenheimer, Matt (June 20, 2016). "What Donald Trump Learned From Joseph McCarthy's Right-Hand Man". The New York Times. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ Kranish, Michael; O'Harrow, Robert Jr. (January 23, 2016). "Inside the government's racial bias case against Donald Trump's company, and how he fought it". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Dunlap, David (July 30, 2015). "1973". Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ Brenner, Julie (June 28, 2017). "How Donald Trump and Roy Cohn's Ruthless Symbiosis Changed America". Vanity Fair. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ "Donald Trump: Three decades, 4,095 lawsuits". USA Today. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ^ a b O'Connor, Clare (April 29, 2011). "Fourth Time's A Charm: How Donald Trump Made Bankruptcy Work For Him". Forbes. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ^ a b Winter, Tom (June 24, 2016). "4Trump Bankruptcy Math Doesn't Add Up". NBC News. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- ^ Flitter, Emily (July 17, 2016). "Art of the spin: Trump bankers question his portrayal of financial comeback". Reuters. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Smith, Allan (December 8, 2017). "Trump's long and winding history with Deutsche Bank could now be at the center of Robert Mueller's investigation". Business Insider. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Lipton, Eric; Protess, Ben; Eder, Steve (January 12, 2021). "An Urgent Reckoning for the Trump Brand". The New York Times.

- ^ "Trump sues Deutsche Bank and Capital One over Democrat subpoenas". BBC News. April 30, 2019. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- ^ Fahrenthold, David; Bade, Rachael; Wagner, John (April 22, 2019). "Trump sues in bid to block congressional subpoena of financial records". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- ^ Savage, Charlie (May 20, 2019). "Accountants Must Turn Over Trump's Financial Records, Lower-Court Judge Rules". The New York Times.

- ^ Merle, Renae; Kranish, Michael; Sonmez, Felicia (May 22, 2019). "Judge rejects Trump's request to halt congressional subpoenas for his banking records". The Washington Post.

- ^ Flitter, Emily (May 22, 2019). "Deutsche Bank Can Release Trump Records to Congress, Judge Rules". The New York Times.

- ^ Hutzler, Alexandra (May 21, 2019). "Trump's appeal to keep finances away from Democrats goes to court headed by Merrick Garland". Newsweek.

- ^ Vogel, Mikhaila (June 10, 2019). "Trump Legal Team Files Brief in Mazars Appeal". Lawfare. Retrieved June 12, 2019.

- ^ Merle, Renae (May 28, 2019). "House subpoenas for Trump's bank records put on hold while President appeals". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 28, 2019.

- ^ Markazi, Arash (July 14, 2015). "5 things to know about Donald Trump's foray into doomed USFL". ESPN.

- ^ Morris, David (September 24, 2017). "Donald Trump Fought the NFL Once Before. He Got Crushed". Fortune. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ "Trump Gets Tyson Fight". The New York Times. February 25, 1988. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- ^ O'Donnell & Rutherford 1991, p. 137.

- ^ Hogan, Kevin (April 10, 2016). "The Strange Tale of Donald Trump's 1989 Biking Extravaganza". Politico. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- ^ Salpukas, Agis (October 6, 1989). "American Air Gets Trump Bid Of $7.5 Billion". The New York Times.

- ^ Janson, Donald (February 23, 1987). "Trump Ends His Struggle to Gain Control of Bally". The New York Times.

- ^ Kessler, Glenn (August 11, 2016). "Too good to check: Sean Hannity's tale of a Trump rescue". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ Blair, Gwenda (October 17, 2018). "Did the Trump Family Historian Drop a Dime to the New York Times?". Politico. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ a b Koblin, John (September 14, 2015). "Trump Sells Miss Universe Organization to WME-IMG Talent Agency". The New York Times. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ Nededog, Jethro (September 14, 2015). "Donald Trump just sold off the entire Miss Universe Organization". Business Insider. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ Rutenberg, Jim (June 22, 2002). "Three Beauty Pageants Leaving CBS for NBC". The New York Times. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ^ de Moraes, Lisa (June 22, 2002). "There She Goes: Pageants Move to NBC". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ^ Zara, Christopher (October 29, 2016). "Why the heck does Donald Trump have a Walk of Fame star, anyway? It's not the reason you think". Fast Company. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ^ Puente, Maria (July 1, 2015). "NBC to Donald Trump: You're fired". USA Today. Retrieved July 28, 2015.

- ^ Gitell, Seth (March 8, 2016). "I Survived Trump University". Politico. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- ^ Cohan, William D. "Big Hair on Campus: Did Donald Trump Defraud Thousands of Real Estate Students?". Vanity Fair. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- ^ Barbaro, Michael (May 19, 2011). "New York Attorney General Is Investigating Trump's For-Profit School". The New York Times.

- ^ Halperin, David (March 1, 2016). "NY Court Refuses to Dismiss Trump University Case, Describes Fraud Allegations". HuffPost.

- ^ Lee, Michelle Ye Hee (February 27, 2016). "Donald Trump's misleading claim that he's 'won most of' lawsuits over Trump University". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- ^ McCoy, Kevin (August 26, 2013). "Trump faces two-front legal fight over 'university'". USA Today.

- ^ Barbaro, Michael; Eder, Steve (May 31, 2016). "Former Trump University Workers Call the School a 'Lie' and a 'Scheme' in Testimony". The New York Times. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ Montenaro, Domenico (June 1, 2016). "Hard Sell: The Potential Political Consequences of the Trump University Documents". NPR. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- ^ Eder, Steve (November 18, 2016). "Donald Trump Agrees to Pay $25 Million in Trump University Settlement". The New York Times. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ Tigas, Mike; Wei, Sisi. "Nonprofit Explorer – ProPublica". ProPublica. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ^ Fahrenthold, David A. (September 1, 2016). "Trump pays IRS a penalty for his foundation violating rules with gift to aid Florida attorney general". The Washington Post.

- ^ Fahrenthold, David A.; Helderman, Rosalind S. (April 10, 2016). "Missing from Trump's list of charitable giving: His own personal cash". The Washington Post.

- ^ Solnik, Claude (September 15, 2016). "Taking a peek at Trump's (foundation) tax returns". Long Island Business News.

- ^ Cillizza, Chris; Fahrenthold, David A. (September 15, 2016). "Meet the reporter who's giving Donald Trump fits". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ^ Bradner, Eric; Frehse, Rob (September 14, 2016). "NY attorney general is investigating Trump Foundation practices". CNN. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

- ^ Fahrenthold, David A. (October 3, 2016). "Trump Foundation ordered to stop fundraising by N.Y. attorney general's office". The Washington Post.

- ^ Jacobs, Ben (December 24, 2016). "Donald Trump to dissolve his charitable foundation after mounting complaints". The Guardian. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ^ Isidore, Chris; Schuman, Melanie (June 14, 2018). "New York attorney general sues Trump Foundation". CNN. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ Thomsen, Jacqueline (June 14, 2018). "Five things to know about the lawsuit against the Trump Foundation". The Hill. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ Goldmacher, Shane (December 18, 2018). "Trump Foundation Will Dissolve, Accused of 'Shocking Pattern of Illegality'". The New York Times. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ^ Katersky, Aaron (November 7, 2019). "President Donald Trump ordered to pay $2M to collection of nonprofits as part of civil lawsuit". ABC News. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- ^ "Judge orders Trump to pay $2m for misusing Trump Foundation funds". BBC News. November 8, 2019. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- ^ Buncombe, Andrew (July 18, 2016). "Trump boasted about writing many books – his ghostwriter says otherwise". The Independent. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- ^ a b Mayer, Jane (July 18, 2016). "Donald Trump's Ghostwriter Tells All". The New Yorker. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- ^ O'Neil, Luke (June 2, 2020). "What do we know about Trump's love for the Bible?". The Guardian. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ LaFrance, Adrienne (December 21, 2015). "Three Decades of Donald Trump Film and TV Cameos". The Atlantic.

- ^ Lockett, Dee (June 21, 2016). "Yes, Donald Trump Did Actually Play a Spoiled Rich Kid's Dad in The Little Rascals". Vulture.com. Retrieved July 14, 2018.

- ^ Lelinwalla, Mark (March 4, 2016). "Looking Back at Donald Trump's WWE Career". Tech Times. Retrieved July 6, 2019.

- ^ Kelly, Chris; Wetherbee, Brandon (December 9, 2016). "Heel in Chief". Slate. Retrieved March 5, 2019.

- ^ Kranish & Fisher 2017, p. 166.

- ^ Silverman, Stephen M. (April 29, 2004). "The Donald to Get New Wife, Radio Show". People. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- ^ Tedeschi, Bob (February 6, 2006). "Now for Sale Online, the Art of the Vacation". The New York Times. Retrieved October 21, 2018.

- ^ Montopoli, Brian (April 1, 2011). "Donald Trump gets regular Fox News spot". CBS News. Retrieved July 7, 2018.