User:Auntieruth55/Breitenfeld collaboration

The Battle of Breitenfeld (German: Schlacht bei Breitenfeld; Swedish: Slaget vid Breitenfeld) or First Battle of Breitenfeld (sometimes First Breitenfeld) , was fought at the crossroads village of Breitenfeld approximately [convert: needs a number] from the walled city of Leipzig on September 17, 1631[1]September 7 (old style or pre-acceptance of the Gregorian calendar in the Protestant region) September 17 (new style, or Gregorian dating), 1631. Breitenfeld represented the Protestants’ first major victory of the Thirty Years War. Since the onset of hostilities in 1618, Protestant forces had been steadily and systematically defeated. The Protestant victory ensured that the German states would not be forcibly reconverted to Roman Catholicism. The victory further confirmed of Sweden’s Gustavus Adolphus of the House of Vasa as a great tactical leader and induced many Protestant German states to ally themselves with Sweden against the German Catholic League, led by Maximilian I, Elector of Bavaria, and the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II of Austria.

Prelude to the Swedish phase of the Thirty Years War[edit]

If the first phase of the Thirty Years War, or Wars, as some historians call it Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page). At issue was the larger problem of imperial rule and princely autonomy: at its most basic, the argument was over the nature of power and authority in the Holy Roman Empire.

When he had planned this invasion in 1629, after peace with Poland, money in his pocket, and promises of French subsidy, he ruled an orderly and loyal country; he possessed reserves of war material; he had at his command an effective, well disciplined fighting force. Gustavus’ efforts in Poland and Lithuania did not secure his Baltic possessions, nor did it solve his kingdom’s security issues; Polish, Lithuanian and English ships continued to prey upon Swedish trade, and Gustavus considered his engagement in the Protestant causes in the German states to be part and parcel to securing his own interests in the Baltic. Initially, Sweden’s entrance into the war was considered a minor annoyance to the Catholic League and its allies; his only battles to this point had been inconclusive ones, or fought against generals of modest military ability, such as at Honigfeld, a minor affair in eastern Prussia against Imperial troops under Hans Georg von Arnim-Boitzenburg to aid Sigismund III of Poland-Lithuania, which ended in Fall 1629 with the Truce of Altmark.

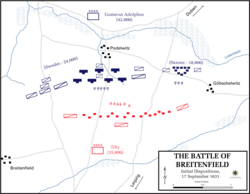

Consequently, when Gustav Adolph landed with a force of 13,000 men at Peenemünde in 1630, the Imperial Commander of the German Catholic League, Tilly, did not immediately respond, being engaged in what seemed to be more pressing matters in northern Italy. Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page). Gustavus and John George united their forces, planning to meet Tilly somewhere near Leipzig; Tilly arrayed his forces north of Leipzig at the crossroads between Breitenfeld and Seehausen.

Disposition of forces[edit]

The Imperial and Catholic League forces arranged their army in regiments of infantry and cavalry. The infantry formed up in large blocks of about 1500 men each, with a front of 150 men and a depth of 10 men. The center comprised pikemen with supporting units of musketeers on each flank.<ref> “Meade”, 175-178. /ref> The Imperial army comprised fourteen such formations, twelve arranged in groups of three blocks, with the center block placed slightly ahead of the other two. The final two regiments were attached one each to the right and left wings. The cavalry was drawn up on each flank; Pappenheim commanding the left, and Fürstenburg, the right. The left flank was close by Breitenfeld; the right, by the village of Seehausen. Tilly had no reserves except for some cavalry placed behind his infantry.

Swedish-Saxon forces in Blue

Catholic army in Red

Unlike Tilly, Gustavus arranged his forces in two long lines. Each line was five men deep for pikemen, and six men deep for musketeers. His use of linear tactics enabled Gustavus to create a front that matched Tilly's, while allowing him troops to keep in reserve. Gustavus’ 14,842 foot soldiers, and 800 cavalry were considered among the finest in Europe; the Elector of Saxony arranged his own forces in the traditional formation on the Swedish left, and all commanders placed most of their cavalry on their flanks; the Saxon forces included 13,000 infantry, either raw recruits or militia, and 5200 cavalry. Since the Swedish and Saxon forces deployed separately, this placed cavalry in their center as well as on their flanks.

Battle[edit]

The 6-7 hour battle can be divided into three parts: Opening Gambits, Thwarting the Imperial attack, and Annihilation of the Imperial army. During these hours, two thirds of the Imperial/Catholic league force vanished; 120 standards of the Imperial and Bavarian army were taken (and are still on display in the Riddarholm church in Stockholm; The combined Swedish-Saxony forces were oriented to the north of Leipzig centered about hamlet of Podelwitz, facing towards Breitenfeld and Leipzig. The battle began around mid-day, with a two hour exchange of artillery fire, during which the Swedes demonstrated fire power in a rate of fire of three-to-five volleys to one Imperial volley. Gustavus had lightened his artillery park, and each colonel had four highly mobile, rapid firing, copper-cast three pounders, the cream of Sweden’s metallurgical industry. <ref“Meade”, p 175./> When the artillery fire ceased, Pappenheim's Black Cuirassiers charged the Swedish line seven times, and were consistently beaten back by harquebus and pikemen. Gustavus had trained his men to aim for the cavalry mounts, and the falling horseflesh made holes in the Catholic formations. The same tactics would worked an hour or so later when the imperial cavalry charged the Swedish left flank. Following the rebuff of the seventh assault, General Banér sallied forth with both his light (Finnish and West Gotlanders ) and heavy cavalry (Smalanders and East Gotlanders). Banér’s cavalry had been taught to deliver its impact with the saber, not to caracole with the hard-to-aim pistols or carbines <ref “Meade”, 175/ref>, forcing Pappenheim and his cavalry quit the field in disarray, retreating to Halle.

Swedish-Saxon forces in Blue

Catholic army in Red

During the Cuirassiers charges, Tilly's infantry had remained stationary, but then the cavalry on his right charged the Saxon cavalry and routed it towards Eilenburg. There may have been confusion in the imperial command at seeing Pappenheim’s charge; military historians, in their assessment of the battle, wonder if Pappenheim precipitate an attempted double envelopment, or did they perform what was the first of Tilly’s preconceived plan. <ref “Meade”, 179./ref> At any rate, seeing an opportunity, Tilly sent the majority of his infantry against the remaining Saxon forces in an oblique march diagonally across his front.

Swedish forces in Blue

Catholic army in Red

As Tilly was ordering his infantry to march ahead diagonally to the right, looking to roll up the Swedish line on its abandoned left flank, Gustavus reordered his second line, under the capable and steady General Gustav Horn, into an array at a right angle to the front, in a maneuver known as refusing the flank. The Swedish line thus developed a strong angle, anchored in the new center under General Lennart Torstenson , whose men were able to deliver an artillery barrage with an overwhelmingly high of rate of fire for the era. Tilly's right flank cavalry preceded his infantry across the field. Except for his musketeers, the infantry had yet to engage. Tilly's seventeen Tercios could only angle across the field. Tercios cannot turn easily, owing to the length of pikes extending through the faces of the essentially square formations. As they advanced obliquely, it left the Swedish right uncovered and free.

Swedish forces in Blue

Catholic army in Red

While this was taking place, the Swedish cavalry re-formed, and, preceded by the Finnish light cavalry (Hakkapeliittas), which Gustavus led personally, attacked across the former front to capture the Imperial artillery, followed in short succession by Banér's heavy cavalry and three regiments of infantry. This not only freed the Swedish field guns from an ongoing artillery duel, but allowed Gustavus's cross-trained cavalry to turn the captured Imperial guns upon Tilly's seventeen own Tercios, now outflanked and badly out of position. Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page).

Gustavus’ soldiers hurriedly redeployed the captured artillery into a new line and angled so it could fire on the Catholic forces. Its position lay slightly to the rear of the Catholics on what had become the extreme right flank of a developing infantry battle. The unwieldy Catholic infantry was trapped and caught in a crossfire of grazing artillery balls which were aimed to bounce and careen into the rank and files between knee and shoulder height—killing and wounding dozens with each ball. With these guns cutting into one end of Tilly's line, and the Swedish center showing no signs of breaking, the exchange of gunfire soon wore down the Imperial troops, and their lines ground to a halt against Horn's infantry.

After several hours of punishment, nearing sunset, the Catholic line finally broke. Tilly himself was injured twice by a so-called "piece of battle"—artillery propelled debris, such as a careening pikehead. Although the first time he had remounted his horse, the second wound was more severe; he was carted off to safety under the cover of night, unconscious during the ensuing retreat, which quickly became a rout as the Catholic forces reached the nearby woods. The totally disorganized and demoralized force effectively lost all cohesion with the fall of night, and the desertion rate was consequently higher than the battle losses. In effect, Gustavus had entirely destroyed the only army the Catholics had in the field, reducing them to a defensive posture.

Gustavus proceeded rapidly on Halle, following the track that Tilly had taken coming east to enforce the Edict of Restitution on the Electorate of Saxony. Two days later his forces captured another 3,000 men after a brief skirmish at Merseburg, and took Halle two days after that.

Aftermath[edit]

The Battle of Breitenfeld served as major endorsement of the linear tactics of Gustavus Adolphus. In traditional battle tactics, the cavalry lined up on either side of the primary infantry force, theoretically protecting its flanks, but in actuality, cavalry would attempt to drive off the opposing force, leaving the infantry’s flank exposed. Gustavus mixed infantry heavily weighted with musketeers among the cavalry in their "starting positions" on the flanks. As opposing cavalry attacked, the musketeers could pick them off, long before the cavalryman’s pistols could be useful. The thinner pike wall sufficiently prevented breakage of the line, but it could also be easily shifted, to allow Gustavus’ cavalry to pass through. Normally detached infantry would be easily run down, but by being placed in the midst of the cavalry, if the opposing force did charge, they would do so right into the Swedish cavalry's own pistols. It was Gustavus' policy to have each arm support the other, so demonstrating an early appreciation of the benefits of combined arms tactics, though long before the term was coined.

In the traditional square, muskets at the rear or sides of the formation could not fire effectively due to the ranks in front. The Dutch had thinned out their formations to place more men at the front, a concept Gustavus adapted by converting his formations into rectangles only six ranks deep (as opposed to ten or more). This became known as a linear formation, and in historical terms, by one modification or another, it persisted in warfare right up to World War II. [citation needed] Additionally, whereas the typical pike-and-shot formation placed the shot on the flanks of a full pike square in the middle to overcome the friendly fire issue mentioned above, Gustavus placed most of the shot at the front, with the pike at the sides strictly in support, with a smattering of pike to keep charging cavalry at bay. In the common ‘’tercio’’ of the day, the ratio of pikes to shot was generally about 2:1; Gustavus' armies were recast to ratios between 3:2 and sometimes approached 1:1—giving his forces a much greater amount of long range fire power.Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page).

Along the same line of rate of fire thinking, he also placed small cannons, or so called infantry guns among the units (Highly mobile, lightweight three-pound brass cannon, by some called the first field artillery). Loaded with canister or grapeshot as formations closed, they were devastating—huge shotguns capable of gutting an opponent's formations. At long ranges, they employed solid shot aimed to bounce through the enemy's ranks doing nearly as much damage. This positioning allowed his battalions to continue to have cannon support even if the battalion became detached from the main force, or was deployed so that it was isolated from the bigger guns that were normally always massed at the center of the field by prior practitioners of tactics.[citation needed] These changes also made Gustavus's formations easier to maneuver on the battlefield; the line formations he fielded could easily turn to face a new direction, compared to the squares Tilly and the Saxon Elector had been using— where the line of march was typically fixed (else the unit would spear each other in turning the unwieldy pikes), once a unit took up positions in the field—his forces were able to change facings and march a different direction. Gustavus' main formations could be re-aligned, even under fire, and even those where his mixed units used his concept of combined arms, although at the cost of some confusion while the pikemen reformed on the shot's flanks, the cavalry paraded back around and came up again.[citation needed]

After the battle, the Catholic League or Imperial army under Tilly could field an army of only 7,000 men. Gustavus Adolphus, on the other hand, had a larger army after the battle than before. The battle's outcome had the political effect of convincing Protestant states to join his cause and convinced France to throw its whole hearted support to the militarily strong but economically weak Sweden. Finally, with the seventy-two year old Tilly's recovery far from certain, Emperor Ferdinand II had no choice but to rehire Wallenstein.

The Battle in modern culture[edit]

The Battle of Breitenfeld (first) is a focal point of the work of fiction, 1632, by Eric Flint. The 1632 series, or Ring of Fire series, is a well researched fictional alternate history, in which specific events of the past transform the present.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- C.V. Wedgwood, The Thirty Years War (New York: Book of the Month Club, 1995)

- Richard A. Preston, et al., Men in Arms, 5th ed., (Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace, 1991)

- Archer Jones, The Art of War in the Western World (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987)