User:AustralianParalympicTech/sandbox

Technological changes at the Paralympic games for Australian Athletes have had major impacts on the types of sports that are played and how those sports are played. Assistive technology in sports can be “low-tech” or can be highly advanced. Over the past decades technology at the Paralympic Games has become more specialised, where the development of the technologies and equipment are tailored to individual athletes and purposes [1]

Archery[edit]

Para-archery is one of the original competitions that has been run since the original Paralympic games in 1960. It is open to athletes who have physical impairments who use assistive devices which are allowed under the classification rules. [2] Some adaptations that are allowed are:

- Mechanical releases on the bow,

- Mouth slings, tabs or mounts for people with restricted arm movement,

- An assistant to relay information about position of arrows on target or to help nock the arrow to the bow,

- Strapping to support the body onto the wheelchair,

- Sight aids,

- Prosthesis with specialised attachments, [3]

- Wheelchairs with additional back support.

-

Xx1164 - Daphne Ceeney at archery Tokyo Games - 3a - Scan

-

Xx1164 - Roy Fowler at archery Tokyo Games - 3a - Scan

-

211000 - Archery Natalie Cordowiner shoots 3 - 3b - Sydney 2000 match photo

Cycling[edit]

Visually impaired athletes use the same type of equipment to able bodied athletes in a tandem format. There are a large range of prosthesis which allow for disabled athletes to participate in cycling. These include leg and arm prosthesis to allow for athletes to use the same types of bikes that able bodied athletes use. Prosthesis used for cycling are often very expensive and are manufactured from materials such as carbon fibre [4]. New materials and methods such as 3D printing are being investigated in the aim to reduce the cost of prosthesis and to improve comfort for athletes.[5]

-

Australian Cycling Team in Atlanta 1996 Paralympic Games

-

75 ACPS Atlanta 1996 Cycling Paul Lake

-

221000 - Cycling track Tania Modra Sarnya Parker action - 3b - 2000 Sydney race photo

Hand Cycling[edit]

Hand cycles initially developed due to a desire by people with impairments to participate in sports alongside able bodied athletes. There are two types of hand cycles that are used in the Paralympic Games, these are recumbent and kneeling chairs. Racing hand cycles often have many gears, which can range from 1 to 33.[6] Hand cycles are often constructed of materials such as aluminium, titanium and carbon fibre.

-

080912 - Stuart Tripp - 3b - 2012 Summer Paralympics

-

U.S. Navy Yeoman 1st Class Javier Rodriguez Santiago, assigned to the Transient Personnel Unit office at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Hawaii, rolls to the finish line in ninth place with a time of 26-39 130512-N-DT940-122

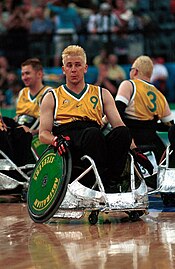

Wheelchair Basketball[edit]

Wheelchair basketball is an adaptation of the able-bodied version. Since the beginning of wheelchair basketball in 1946 [7] there have been significant changes in wheelchair technology. Modern wheelchairs used in wheelchair basketball have highly cambered wheels (to prevent injury to players hands). There have also been the addition of rear castor wheels to prevent falling backwards, and high tech materials such as carbon fibre and titanium are being used in the seats[8], frames and spokes[9].

-

41 ACPS Atlanta 1996 Basketball Troy Sachs

-

201000 - Wheelchair basketball David Gould reaches - 3b - 2000 Sydney match photo

-

020912 - Amber Merritt - 3b - 2012 Summer Paralympics

Wheelchair Rugby[edit]

Wheelchair rugby is played by athletes with quadriplegia which was played as a demonstration sport at the 1996 Atlanta Paralympic games, it made its debut as a medal sport at the 2000 Sydney Paralympic games. [10] The wheelchairs used in wheelchair rugby are similar to ones used in wheelchair basketball with modifications made to permit contact between wheelchairs and for greater support to counteract decreased trunk control of the quad athlete.[11] These wheelchairs have these following characteristics, they have:

- A higher back for trunk control,

- A greater degree of dump (seat angle) to stop the player from falling forward and to help the player carry the ball in their lap

- Metal shroud covering spokes,

- Forward metal protection for contact,

- High wheel camber to prevent injury to player’s hands. [6]

The wheels used between the 1996 and 2000 Paralympic games were considerably different in their construction. With wheelchairs used in 1996 Atlanta games having a greater resemblance to the wheelchairs used in wheelchair basketball. Wheelchairs designs also allow for specialisations between defensive and offensive positions, these mainly comprise of added components. Offensive chairs often have shrouds to make it harder for opponents to impede them and defensive chairs are designed with bumpers which are designed to impede the opposition.

-

53 ACPS Atlanta 1996 Rugby Steve Porter Garry Croker

-

281000 - Wheelchair rugby Patrick Ryan action 2 - 3b - 2000 Sydney match photo

-

090912 - Ben Newton - 3b - 2012 Summer Paralympics

Shooting[edit]

Shooting is a test of both accuracy and control. In the shooting Para sport events, athletes with physical impairments compete in rifle and pistol events. [12] Disabled shooters use the same firearms and clothing as able bodied shooters however adaptations to equipment are allowed to accommodate for disabilities. These may include rifle and pistol supports, or aids to allow for visually impaired athletes to aim. Technology changes over the past few decades have allowed for visually impaired athletes to compete in shooting events. These athletes use audio signals to guide them in their aiming, with variable pitch and intensity to indicate closeness to the target [13]. Systems such as the Ecoaims VIS500 use infrared LEDs which are placed above the target and are recognised by the camera module within the aiming device. Shooters who compete in wheelchairs (as shown in the photos) compete in special wheelchairs which comply with the governing body's regulations. These wheelchairs have relatively low back support and no arm rests. [14] The mechanical support is used to brace the rifles for shooting.

-

Peter Worsley, Australian paralympic shooter

-

010912 - Bradley Mark - 3b - 2012 Summer Paralympics (01)

-

Australian paralympic shooter, Patricia Fischer shoots

Wheelchair Racing[edit]

Racing wheelchair designs were limited from the 1940s until the 1990s, these restrictions greatly inhibited the innovation and design of racing wheelchairs. Once the restrictions were lifts there became a strongly dominant design. Modern racing wheelchairs have been developed solely for speed, hence they use large rear wheels, a long wheel base, small hand rims and a forward leaning bucket seat. There are three methods to steering racing wheel chairs, by using the handlebars, the compensator or by doing a wheelie. [6] The wheelchairs used at the beginning of wheelchair racing were slightly modified everyday chairs. Modern racing wheelchairs are made of advanced materials such as titanium and carbon fiber, and have a significant amount of research and development that has been undertaken into factors such as rolling resistance and aerodynamics. [15]

-

Rick Hansen

-

Louise Sauvage, wheelchair race, 1992 Paralympics

-

281000 - Athletics wheelchair racing Louise Sauvage action 2 - 3b - 2000 Sydney race photo

References[edit]

- ^ Burkett, B (Feb 2010). "Technology in Paralympic sport: performance enhancement or essential for performance?". Brittish Journal of Sports Medicine. 44 (3): 215–220. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2009.067249. PMID 20231602. S2CID 2722152.

- ^ "Archery". Official website of the Paralympic Movement. 17 October 2017.

- ^ Donahue, Annie Beth (10 May 2017). "What is Wheelchair Archery?". Invecare. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ^ "Irish Paralympic cyclist appeals to donors for new prosthetic leg". Irish Post. 7 May 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ^ Mahon, Lydia. "First 3D Printed Paralympic Cycling Prosthetic to Compete in Rio". Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ^ a b c Cooper, Rory A.; De Luigi, Arthur Jason (August 2014). "Adaptive Sports Technology and Biomechanics, Wheelchairs". Paralympic Sports Medicine and Science. 6 (8 Suppl): 31–39. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2014.05.020. PMID 25134750. S2CID 2215671.

- ^ International Wheelchair Basketball Federation (17 October 2017). "Wheelchair Basketball". Official website of the Paralympic Movement.

- ^ RGK Wheelchairs (18 October 2017). "Carbon Fibre seating system wheelchair". RGK Life.

- ^ Mackenzie, Joel (29 April 2013). "Wheelchair basketball technology pushing limits". International Paralympic Commitee. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ^ Wheelchair Rugby Federation (17 October 2017). "Wheelchair Rugby". Official website of the Paralympic Movement.

- ^ De Luigi, Arthur Jason, ed. (2018). Adaptive Sports Medicine: A Clinical Guide. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. p. 27. ISBN 978-3319565668.

- ^ World Shooting Para Sport (17 October 2017). "About shooting". Official website of IPC Shooting.

- ^ World Shooting Para Sport (18 October 2017). "Visually Impaired Shooting". Official website of IPC Shooting.

- ^ Disabled Shooting Project (2014). "General - Shooter's Wheelchair". Disabled Shooting Project.

- ^ MacLeish, Michael S.; Cooper, Rory A.; Harralson, Joe; Ster, James F. (1993). "Design of a composite monocoque frame racing wheelchair". Journal of Rehabilitation Research. 30 (2): 233–249. PMID 8035352.

Further Reading[edit]

Brittain, I. (2016). The Paralympic Games explained (Second ed.). Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge.

Fliess-Douer, O., Mason, B., Katz, L. and So, C.-h. R. (2016) Sport and technology, in Training and Coaching the Paralympic Athlete: Handbook of Sports Medicine and Science (eds Y. C. Vanlandewijck and W. R. Thompson), John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Oxford, UK.