User:Bendotf/new sandbox

Additional modern nonmonetary explanations[edit]

The monetary explanation has two weaknesses. First it is not able to explain why the demand for money was falling more rapidly than the supply during the initial downturn in 1930–31.[1] Second it is not able to explain why in March 1933 a recovery took place although short term interest rates remained close to zero and the Money supply was still falling. These questions are addressed by modern explanations that build on the monetary explanation of Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz but add non-monetary explanations.

Debt deflation[edit]

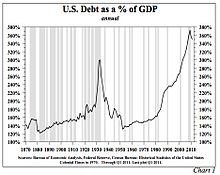

Total debt to GDP levels in the U.S. reached a high of just under 300% by the time of the Depression. This level of debt was not exceeded again until near the end of the 20th century.[2] Jerome (1934) gives an unattributed quote about finance conditions that allowed the great industrial expansion of the post WW I period:

Probably never before in this country had such a volume of funds been available at such low rates for such a long period.[3]

Furthermore, Jerome says that the volume of new capital issues increased at a 7.7% compounded annual rate from 1922–29 at a time when the Standard Statistics Co.'s index of 60 high grade bonds yielded from 4.98% in 1923 to 4.47% in 1927.

There was also a real estate and housing bubble in the 1920s, especially in Florida, which burst in 1925. Alvin Hansen stated that housing construction during the 1920s decade exceeded population growth by 25%.[4] See also:Florida land boom of the 1920s Statistics kept by Cook County, Illinois show over 1 million vacant plots for homes in the Chicago area, despite only 950,000 plots being occupied, the result of Chicago's explosive population growth in combination with a real estate bubble.

Irving Fisher argued the predominant factor leading to the Great Depression was over-indebtedness and deflation. Fisher tied loose credit to over-indebtedness, which fueled speculation and asset bubbles.[5] He then outlined nine factors interacting with one another under conditions of debt and deflation to create the mechanics of boom to bust. The chain of events proceeded as follows:

- Debt liquidation and distress selling

- Contraction of the money supply as bank loans are paid off

- A fall in the level of asset prices

- A still greater fall in the net worths of business, precipitating bankruptcies

- A fall in profits

- A reduction in output, in trade and in employment.

- Pessimism and loss of confidence

- Hoarding of money

- A fall in nominal interest rates and a rise in deflation adjusted interest rates.[5]

During the Crash of 1929 preceding the Great Depression, margin requirements were only 10%.[6] Brokerage firms, in other words, would lend $90 for every $10 an investor had deposited. When the market fell, brokers called in these loans, which could not be paid back. Banks began to fail as debtors defaulted on debt and depositors attempted to withdraw their deposits en masse, triggering multiple bank runs. Government guarantees and Federal Reserve banking regulations to prevent such panics were ineffective or not used. Bank failures led to the loss of billions of dollars in assets.[7]

Outstanding debts became heavier, because prices and incomes fell by 20–50% but the debts remained at the same dollar amount. After the panic of 1929, and during the first 10 months of 1930, 744 US banks failed. (In all, 9,000 banks failed during the 1930s). By April 1933, around $7 billion in deposits had been frozen in failed banks or those left unlicensed after the March Bank Holiday.[8]

Bank failures snowballed as desperate bankers called in loans, which the borrowers did not have time or money to repay. With future profits looking poor, capital investment and construction slowed or completely ceased. In the face of bad loans and worsening future prospects, the surviving banks became even more conservative in their lending.[7] Banks built up their capital reserves and made fewer loans, which intensified deflationary pressures. A vicious cycle developed and the downward spiral accelerated.

The liquidation of debt could not keep up with the fall of prices it caused. The mass effect of the stampede to liquidate increased the value of each dollar owed, relative to the value of declining asset holdings. The very effort of individuals to lessen their burden of debt effectively increased it. Paradoxically, the more the debtors paid, the more they owed.[5] This self-aggravating process turned a 1930 recession into a 1933 great depression.

Fisher's debt-deflation theory initially lacked mainstream influence because of the counter-argument that debt-deflation represented no more than a redistribution from one group (debtors) to another (creditors). Pure re-distributions should have no significant macroeconomic effects.

Building on both the monetary hypothesis of Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz as well as the debt deflation hypothesis of Irving Fisher, Ben Bernanke developed an alternative way in which the financial crisis affected output. He builds on Fisher's argument that dramatic declines in the price level and nominal incomes lead to increasing real debt burdens which in turn leads to debtor insolvency and consequently leads to lowered aggregate demand, a further decline in the price level then results in a debt deflationary spiral. According to Bernanke, a small decline in the price level simply reallocates wealth from debtors to creditors without doing damage to the economy. But when the deflation is severe falling asset prices along with debtor bankruptcies lead to a decline in the nominal value of assets on bank balance sheets. Banks will react by tightening their credit conditions, that in turn leads to a credit crunch which does serious harm to the economy. A credit crunch lowers investment and consumption and results in declining aggregate demand which additionally contributes to the deflationary spiral.[9][10][11]

Economist Steve Keen revived the debt-reset theory after he accurately predicted the 2008 recession based on his analysis of the Great Depression, and recently[when?] advised Congress to engage in debt-forgiveness or direct payments to citizens in order to avoid future financial events.[12] Some people support the debt-reset theory.[13][14][15]

Expectations hypothesis[edit]

Expectations have been a central element of macroeconomic models since the economic mainstream accepted the new neoclassical synthesis. While not rejecting that it was inadequate demand that sustained the depression, according to Peter Temin, Barry Wigmore, Gauti B. Eggertsson and Christina Romer the key to recovery and the end of the Great Depression was the successful management of public expectations. This thesis is based on the observation that after years of deflation and a very severe recession, important economic indicators turned positive in March 1933, just as Franklin D. Roosevelt took office. Consumer prices turned from deflation to a mild inflation, industrial production bottomed out in March 1933, investment doubled in 1933 with a turnaround in March 1933. There were no monetary forces to explain that turnaround. Money supply was still falling and short term interest rates remained close to zero. Before March 1933, people expected a further deflation and recession so that even interest rates at zero did not stimulate investment. But when Roosevelt announced major regime changes people began to expect inflation and an economic expansion. With those expectations, interest rates at zero began to stimulate investment as planned. Roosevelt's fiscal and monetary policy regime change helped to make his policy objectives credible. The expectation of higher future income and higher future inflation stimulated demand and investments. The analysis suggests that the elimination of the policy dogmas of the gold standard, a balanced budget in times of crises and small government led to a large shift in expectation that accounts for about 70–80 percent of the recovery of output and prices from 1933 to 1937. If the regime change had not happened and the Hoover policy had continued, the economy would have continued its free fall in 1933, and output would have been 30 percent lower in 1937 than in 1933.[16][17][18]

The recession of 1937–38, which slowed down economic recovery from the great depression, is explained by fears of the population that the moderate tightening of the monetary and fiscal policy in 1937 would be first steps to a restoration of the pre March 1933 policy regime.[19]

Heterodox theories[edit]

Austrian School[edit]

Austrian economists argue that the Great Depression was the inevitable outcome of the monetary policies of the Federal Reserve during the 1920s. In their opinion, the central bank's policy was an "easy credit policy" which led to an unsustainable credit-driven boom. In the Austrian view, the inflation of the money supply during this period led to an unsustainable boom in both asset prices (stocks and bonds) and capital goods. By the time the Federal Reserve belatedly tightened monetary policy in 1928, it was too late to avoid a significant economic contraction.[20] Austrians argue that government intervention after the crash of 1929 delayed the market’s adjustment and made the road to complete recovery more difficult.[21][22]

Acceptance of the Austrian explanation of what primarily caused the Great Depression is compatible with either acceptance or denial of the Monetarist explanation. Austrian economist Murray Rothbard, who wrote America's Great Depression (1963), rejected the Monetarist explanation. He criticized Milton Friedman's assertion that the central bank failed to sufficiently increase the supply of money, claiming instead that the Federal Reserve did pursue an inflationary policy when, in 1932, it purchased $1.1 billion of government securities, which raised its total holding to $1.8 billion. Rothbard says that despite the central bank's policies, "total bank reserves only rose by $212 million, while the total money supply fell by $3 billion". The reason for this, he argues, is that the American populace lost faith in the banking system and began hoarding more cash, a factor very much beyond the control of the Central Bank. The potential for a run on the banks caused local bankers to be more conservative in lending out their reserves, which, according to Rothbard's argument, was the cause of the Federal Reserve's inability to inflate.[23]

Friedrich Hayek had criticised the FED and the Bank of England in the 1930s for not taking a more contractionary stance.[24] However, in 1975, Hayek admitted that he made a mistake in the 1930s in not opposing the Central Bank's deflationary policy and stated the reason why he had been ambivalent: "At that time I believed that a process of deflation of some short duration might break the rigidity of wages which I thought was incompatible with a functioning economy.[25] In 1978, he made it clear that he agreed with the point of view of the Monetarists, saying, "I agree with Milton Friedman that once the Crash had occurred, the Federal Reserve System pursued a silly deflationary policy", and that he was as opposed to deflation as he was to inflation.[26] Concordantly, economist Lawrence White argues that the business cycle theory of Hayek is inconsistent with a monetary policy which permits a severe contraction of the money supply.

Hans Sennholz argued that most boom and busts that plagued the American economy in 1819–20, 1839–43, 1857–60, 1873–78, 1893–97, and 1920–21, were generated by government creating a boom through easy money and credit, which was soon followed by the inevitable bust. The spectacular crash of 1929 followed five years of reckless credit expansion by the Federal Reserve System under the Coolidge Administration. The passing of the Sixteenth Amendment, the passage of The Federal Reserve Act, rising government deficits, the passage of the Hawley-Smoot Tariff Act, and the Revenue Act of 1932, exacerbated the crisis, prolonging it.[27]

Marxian[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2017) |

Marxists generally argue that the Great Depression was the result of the inherent instability of the capitalist model.[28]

- ^ Robert Whaples, Where Is There Consensus Among American Economic Historians? The Results of a Survey on Forty Propositions., Journal of Economic History, Vol. 55, No. 1 (March 1995), p. 150, in JSTOR

- ^ [1] Several graphs of total debt to GDP can be found on the Internet.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Jerome 1934was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Hansen, Alvin (1939). "Economic Progress and Declining Population Growth". American Economic Review. 29 (March).

- ^ a b c Fisher, Irving (October 1933). "The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions". Econometrica. 1 (4). The Econometric Society: 337–357. doi:10.2307/1907327. JSTOR 1907327.

- ^ Fortune, Peter (Sep–Oct 2000). "Margin Requirements, Margin Loans, and Margin Rates: Practice and Principles – analysis of history of margin credit regulations – Statistical Data Included". New England Economic Review.

- ^ a b "Bank Failures". Living History Farm. Archived from the original on 2009-02-19. Retrieved 2008-05-22.

- ^ "Friedman and Schwartz, Monetary History of the United States", 352

- ^ Randall E. Parker, Reflections on the Great Depression, Edward Elgar Publishing, 2003, ISBN 9781843765509, p. 14-15

- ^ Bernanke, Ben S (June 1983). "Non-Monetary Effects of the Financial Crisis in the Propagation of the Great Depression". The American Economic Review. 73 (3). The American Economic Association: 257–276. JSTOR 1808111.

- ^ Mishkin, Fredric (December 1978). "The Household Balance and the Great Depression". Journal of Economic History. 38 (4): 918–37. doi:10.1017/S0022050700087167.

- ^ Keen, Steve (2012-12-06). "Briefing for Congress on the Fiscal Cliff: Lessons from the 1930s - Steve Keen's Debtwatch". Debtdeflation.com. Retrieved 2014-12-01.

- ^ http://libertyloveandjusticeforall.com/2012/12/08/debt-reset-is-inevitable/

- ^ Friedersdorf, Conor (2012-12-05). "What If the Fiscal Cliff Is the Wrong Cliff?". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2014-12-01.

- ^ "Private Debt Caused The Current Great Depression, Not Public Debt - Michael Clark". Seeking Alpha. Retrieved 2014-12-01.

- ^ Gauti B. Eggertsson, Great Expectations and the End of the Depression, American Economic Review 2008, 98:4, 1476–1516

- ^ The New York Times, Christina Romer, The Fiscal Stimulus, Flawed but Valuable, October 20, 2012

- ^ Peter Temin, Lessons from the Great Depression, MIT Press, 1992, ISBN 9780262261197, p. 87-101

- ^ Gauti B. Eggertsson, Great Expectations and the End of the Depression, The American Economic Review, Vol. 98, No. 4 (Sep., 2008), S. 1476-1516, p. 1480

- ^ Murray Rothbard, America's Great Depression (Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2000), pp. 159–63.

- ^ Rothbard, America's Great Depression, pp. 19–21"

- ^ Mises, Ludwig von (2006). The Causes of the Economic Crisis; and Other Essays Before and After the Great Depression. Ludwig von Mises Institute. p. 207. ISBN 978-1933550039.

- ^ Rothbard, A History of Money and Banking in the United States, pp. 293–94.

- ^ John Cunningham Wood, Robert D. Wood, Friedrich A. Hayek, Taylor & Francis, 2004, ISBN 9780415310574, p. 115

- ^ White, Clash of Economic Ideas, p. 94. See alsoWhite, Lawrence (2008). "Did Hayek and Robbins Deepen the Great Depression?". Journal of Money, Credit and Banking. 40 (4): 751–768. doi:10.1111/j.1538-4616.2008.00134.x.

- ^ F. A. Hayek, interviewed by Diego Pizano July, 1979 published in: Diego Pizano, Conversations with Great Economists: Friedrich A. Hayek, John Hicks, Nicholas Kaldor, Leonid V. Kantorovich, Joan Robinson, Paul A.Samuelson, Jan Tinbergen (Jorge Pinto Books, 2009).

- ^ Sennholz, Hans (October 1, 1969). "The Great Depression". Foundation for Economic Education. Retrieved October 23, 2016.

- ^ "Lewis Corey: The Decline of American Capitalism (1934)". Marxists.org. 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2014-12-01.