User:Blz 2049/sandbox6

| This is not a Wikipedia article: It is an individual user's work-in-progress page, and may be incomplete and/or unreliable. For guidance on developing this draft, see Wikipedia:So you made a userspace draft. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL |

| Author | John Ashbery |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Joe Brainard |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Black Sparrow Press |

Publication date | March 26, 1975 |

| Pages | 101 |

| ISBN | 0-87685-227-4 |

The Vermont Notebook is a book of poetry by John Ashbery with illustrations by Joe Brainard. It was published by Black Sparrow Press on March 26, 1975, shortly before the publication of Ashbery's award-winning poetry collection Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror.

Background[edit]

In the 1950s and early 1960s, Ashbery and Brainard came to be associated with the New York School, a loose milieu of avant-garde poets and artists in and around New York City.[1] According to Holland Cotter, this time was "the great New York moment of painter-poet convergence" marked by fruitful exchange between the visual arts and literature.[2] The New York School scene, which poet Douglas Crase called "a vanguard of friends," included, among others, poets Frank O'Hara, James Schuyler, Barbara Guest, and Kenneth Koch, and artists Jane Freilicher, Larry Rivers, and Grace Hartigan. Much of the artistic collaboration of the time was sparked by simple social proximity; many of the artists and poets lived on the same stretch of West 21st Street during what Dan Chiasson referred to as "the era of cheap New York apartments."[3]

From the beginning of Brainard's career as an artist, Ashbery held his art in high regard. He wrote an essay for the brochure accompanying Brainard's first solo exhibition in 1965, and wrote a positive review in Art News for his third exhibition in 1969.[4] Much later, in an essay accompanying a 1997 retrospective of Brainard's art, Ashbery compared his work to the contemporary pop art of Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein but noted that, unlike the distanced, sometimes mean-spirited attitude of pop art with its "subtext of provocation," in Brainard's work there was a kinder spirit of "confrontation without provocation."[5] Brainard, Ashbery wrote, "was one of the nicest artists I have ever known. Nice as a person and nice as an artist."[5] While "nice" is a somewhat unusual word for art criticism, perhaps even a dismissive one, Richard Deming said that Ashbery "leads us to think about niceness as being itself something more than a sentimentality or fond feeling—as being an artist's invested stance toward the world," while also considering an argument that "'the nice' is as valid a value in art as either the beautiful or the sublime—or, for that matter, the abject."

Brainard also held Ashbery's poetry in high regard, though he expressed his admiration in a characteristically offhanded way. He named Ashbery one of his favorite poets in a 1977 interview, though he said the poet was "over my head ... every now and then I can get into him, and he sweeps me away and I love it, although sometimes he's impossible. My mind wanders off."[6]

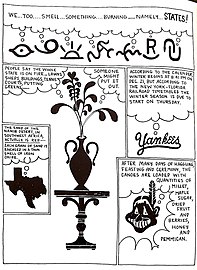

The two had worked together several times on smaller projects before The Vermont Notebook. They first collaborated in 1965 for the second issue in Brainard's C Comics series. Brainard drew these comic strips using a mix of his own original characters alongside popular characters appropriated from the likes of Nancy, Archie, Dick Tracy, and Red Ryder, leaving the speech balloons empty. He then invited poets to fill in the speech balloons with whatever they like, with contributions from writers like Guest, Koch, O'Hara, Schuyler, and Ashbery.[7]

- "The Great Explosion Mystery" (1965) – words by Ashbery, art by Brainard

-

C Comics No. 2 cover

-

First page

-

Second page

-

Third page

-

Fourth page

-

Fifth page

-

Sixth page

In the semi-abstract artwork for Ashbery's contribution, titled "The Great Explosion Mystery", Brainard drew speech balloons for various Major League Baseball team logos and shapes of U.S. states.[8] Later, Brainard painted the cover for a 1970 reprint of Ashbery's debut poetry collection, Some Trees, and after The Vermont Notebook he contributed cover artwork for a 1975 edition of A Nest of Ninnies (1969), a novel co-written by Ashbery and Schuyler, as well as Ashbery's collection Three Plays (1978).[9]

Creation[edit]

Ashbery wrote The Vermont Notebook while traveling by bus through New England. Despite the book's title, his tour did not visit Vermont.[10] Indeed, he said in 1975 that it had been written entirely in Massachusetts.[11]

He challenged himself to write in longhand—a practice he had by then largely abandoned in favor of the typewriter—and, especially, to write in such an unconducive setting. In a 1984 interview, he compared the process to automatic writing, and called the book a "a kind of messy grab bag as the word notebook implies" and "a catalogue of a number of things that could be found in the state of Vermont, as well as almost everywhere else—another 'democratic vista.'"[10]

- Brainard

Brainard had a deeper connection to Vermont, having spent most summers from 1965 onward in the small town of Calais with his romantic partner Kenward Elmslie. He produced numerous works of art during these summers in Vermont, mostly cutout collages, still lifes, and landscapes.[12] Brainard made the illustrations for VN after Ashbery had already written the book.[13] Same process as his illustrations for Living With Chris by Ted Berrigan[14]

Publication[edit]

The first 18 pages of The Vermont Notebook appeared in early 1974 within the second issue of Z, a small press periodical run by the Vermont-based Z Press.[15] Another portion, corresponding to pages 53–101 of the first edition, was published in Statements: New Fiction from the Fiction Collective, an anthology of avant-garde, genre-defying works of fiction.[16] The acknowledgements section of The Vermont Notebook indicated that the Fiction Collective anthology had been "published previously" and, conversely, Ashbery's bio in Statements indicated that The Vermont Notebook was "shortly to be published in its entirety"; however, the March release of The Vermont Notebook arrived months before Statements, which actually came out in August.[17]

Los Angeles-based Black Sparrow Press published the book on March 26, 1975. The first edition was a run of 2,190 copies, with a list price of $3.50 (equivalent to about $15 in 2023, adjusted for inflation).[18] Two special editions were released simultaneously with the regular first edition. An additional 250 numbered copies, signed by Ashbery and Brainard, were sold for $15 each (about $66 in 2023). A "deluxe" edition of 26 hand-bound copies, also signed by both authors, carried a price of $50 (about $220 in 2023).[19] Each "deluxe" copy was labeled with a letter and included a unique, original ink drawing by Brainard.[18]

Following the initial publication, it remained out of print and largely inaccessible for decades.[20] Then, in 2001, Granary Books and Z Press published a new edition.[21] The Library of America included the book's full contents in its 2007 volume of Ashbery's Collected Poems 1956–1987.[22] A short portion was republished in the Spring–Summer 2008 double issue of The Massachusetts Review.[23]

Contents and analysis[edit]

A riff on the American travelogue (Ashbery notes 'most of it was written on a bus'); a tour of the everyday (with nods to Stein's Tender Buttons, Williams's Spring and All, Stevens's 'Man on the Dump', Eliot's Waste Land, Duchamp's readymades, and Warhol's pop art); a mutating experiment in form (including Whitmanian catalogs, prose poems, lyrics, postcards, the collaging of found texts, and the recycling of old poems); a curiosity cabinet of the American vernacular; an urban pastoral; a rendering of homoerotic desire; and a self-reflexive meditation on collections and trash, dumps and dumping: in short, the text of The Vermont Notebook is capacious in form and content.

Susan Rosenbaum[24]

The Vermont Notebook contains 47 pages of text and 47 pages of illustration.[21] Ashbery wrote the bulk of the book in the style of prose poetry, although there are segments of verse.[25] It resembles a journal, diary, or travelogue, with each page or "entry" standing on its own to some degree.[21] But according to David Shapiro, the book resists being placed within a single genre or even defined by the terms of its own title, being "not quite a 'notebook'" and "not of Vermont", except for perhaps "a mental, symbolist Vermont".[26] Its overall structure is ambiguous, with critics typically describing it as either a single book-length long poem or as a series of fragmentary, mostly untitled short poems whose beginnings and endings are not clearly delineated as such.[22]

Ashbery uses collage and cut-up technique throughout, borrowing liberally from everyday language. He repurposes clichés of vernacular American English, incorporating the diction of contemplative faux diary entries, banal welcomes into commercial spaces, and paranoiac conspiracy theory babble.[27] In addition to these "simulations" of commonplace American language, he appropriates text outright from other sources—for example, he reproduces found text from a postcard (dated 1949 and signed by "Em & Edythe") and, in the final three pages, the text of his own (otherwise unpublished) poem "American Notes".[28]

List-making[edit]

Lists are a recurring structural element. While Ashbery had already made distinctive use of lists in his poetry, and continued to do so long after, the Notebook pushes this tendency to the extreme.[29] In Christopher Schmidt's reading, these lists generate "a kind of dream-like landscape of suburban postwar America, where everyone is an expert on what is for sale and on what brands possess the most currency."[30] Critics have discussed the influence of W. H. Auden and Walt Whitman on the book's extensive lists.[note 1] Though most of the lists are united by some common theme or subject, some contain errant or misfit items that throw their apparent unity into doubt or make their true scope unclear; for example, a list that begins with "Front porches, back porches, side porches" eventually grows to include "trees, magnolia, scenery, McDonald's, Carrol's, Kinney Shoe Stores."[29]

Most of the lists are presented as pairs in juxtaposition. Some of the pairs are games and crimes; places in North America and names of newspapers; and voluntary or community-based organizations ("Bridge clubs, Elks, Kiwanis, Rotary, AAA, PTA, lodges, Sunday school ...") and corporations ("Gulf Oil, Union Carbide, Westinghouse, Xerox, Eastman Kodak, ITT, Marriott ...").[33]

Another pair of lists is composed of the names of real people, many of whom were Ashbery's friends.[34] While there is considerable overlap and gray area between the two lists, the first tends toward people associated with the commercialized art world and the other toward (implicitly noncommercial) poetry.[35] According to David Shapiro, the "cemetery-like listing" of names ranks as one of the poet's most profound "successes" of the 1970s—but also "one of the most horrific jokes" in his poetry. As the names accumulate, they become an "almost murderous act of 'un-naming'", creating an effect of linguistic derealization and "present[ing] us with the terrible arbitrariness of all language, the names so distant from their seeming objects, torn from their place in everyone's dream of coherence."[34]

Sexuality[edit]

One of the few segments of the book bearing a title, "The Fairies' Song" is noteworthy as one of the "poems in Ashbery's oeuvre that are obviously thematically centered around homosexuality." Subjects of the poem, treated in allegorical terms, include the special affinity for "song" or poetry in LGBT culture and the struggles of living as a gay man within a homophobic society.[36]

Ecological themes[edit]

John Shoptaw observed that "five pages of seemingly parodic discourse, calmly inventorying ecological disasters, are taken verbatim"[27]

Through observation of "environmental transformation in scenes of dumps, commodified suburban landscapes, and altered ecosystems," The Vermont Notebook reveals "how systemic disruption might be collectively felt before it is fully understood, but also how we can ignore or misperceive disturbing signs."[37]

- 2014 In The Poetics of Waste: Queer Excess in Stein, Ashbery, Schuyler, and Goldsmith, Christopher Schmidt advocated for reading The Vermont Notebook as subversive ecopoetry with a queer sensibility, and a "critique of pastoralism and of a nature poetry that would see wilderness as a masculine retreat from the wastes of the city."[38]

Illustrations[edit]

- Description of the illustrations as they are/Brainard's process and relationship to the text

Illustrations in India ink[39]

Brainard: "I divided it up by pages and I started in the middle and just tried to add to the poem but not to illustrate it. I tried to relate at certain points but in factual ways, not in emotional ways."[14]

"This is typical of the way Brainard worked with text, because he believed that illustrations in the strict sense of the word destroy writing by making it too specific."[12]

"Brainard gave a look of offhand ease to the pictures he made for his friends' publications. Most of these were small press productions, books of poetry by Ron Padgett, Ted Berrigan, Kenward Elmslie, John Ashbery, and others ... Poets in this milieu have a liking for the American vernacular, which they employ with admiration, irony, and the occasional burst of silliness. In the faux anonymity of Brainard's illustrations, their variations on everyday speech found the visual equivalent of a sounding board. What Brainard shared with his poet friends was an esthetic of the ordinary accepted, and transformed but not betrayed—not made fancy—in the acceptance."[39]

- Critical interpretation

Not ekphrasis[40] As sequential art, it is not narrative but nevertheless the sequence accumulates meaning and the whole is greater than the sum of its2 parts.[41]

- 2009 Encyclopedia of the New York School of Poets: "The juxtaposition of drawing and writing are crucial to the full experience of the book, creating otherwise impossible, fantastic, and complete images."[42]

Critical reception[edit]

The Vermont Notebook received little critical notice upon release and continues to be seen, in general, as a comparatively minor book within Ashbery's overall body of work. Ellen Levy said it "may be the least discussed of Ashbery's books,"[43] while Ron Silliman asserted it was one of Ashbery's "most under-appreciated" books.[note 2] Geoff Ward deemed it "his most underrated text," noting that although critics had received his earlier collection The Tennis Court Oath with the "most abuse," they had "merely ignored The Vermont Notebook altogether."[47] The book's relative critical neglect may have been a result of its longstanding scarcity and unavailability.[48]

Comparisons with Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror[edit]

Published in May 1975, Ashbery's collection Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror largely overshadowed The Vermont Notebook. Self-Portrait won the Pulitzer Prize, National Book Award, and National Book Critics Circle Award—remaining, to date, the only book to win all three awards—and established Ashbery as one of the preeminent living American poets.

Critics have typically regarded The Vermont Notebook as more avant-garde than Self-Portrait—for example, John Shoptaw called it "a wastebasket for all the extraneous poetic matter ruled out by its famed contemporary."[49] To some critics, it was not merely less conventional than Self-Portrait but even fatally niche by comparison, appealing only to Ashbery's immediate social circle in the avant-garde. David Bromwich gave it a passing mention in his contemporaneous review of Self-Portrait, labeling it "a queer little pseud of a book" and "a heartfelt salute to old peers" that reflected Ashbery's beginnings as "the poet of a coterie." By contrast, for Bromwich Self-Portrait represented the culmination of Ashbery's irrepressible talents, showing him to be "the property of a larger audience" and "the great original of his generation" who "belongs, in fact, to everyone interested in poetry, or modern art, or just the possibility of change."[50] In a 2003 review for World Literature Today, John Boening echoed the sentiment that The Vermont Notebook catered to Ashbery's New York School peers but offered little to a general audience: "One gets the feeling that there are likely a number of inside jokes here for the cognoscenti who used to gather in the Village or the Hamptons, but one can grow daffy trying to tease them out. ... What this wacky (a term used in one of the cover blurbs) experiment adds to Ashbery's reputation is anyone's to guess."[21]

Reassessments[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ In a high school essay, Ashbery had praised list-making as a thoroughly modern feature of the poetry of W. H. Auden; in this respect, The Vermont Notebook is a key example of Auden's influence.[31] Others have identified Walt Whitman, who was also known for expansive lists, as the crucial stylistic predecessor.[32]

- ^ Silliman described two broad categories of Ashbery's books of poetry. The first group, typified by The Double Dream of Spring (1970) and increasingly prevalent as his career progressed, are books of about 100 pages filled with short lyric poems.[44] The books Silliman placed in the second, more idiosyncratic group—including The Tennis Court Oath (1962), Rivers and Mountains (1966), Three Poems (1972), Flow Chart (1991), and Girls on the Run (1999)—vary wildly in structure and style, as distinct from the first group as they are from each other.[45] According to Silliman, The Vermont Notebook is "the most under-appreciated" of this latter group.[46]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Lewallen 2001, p. 12.

- ^ Cotter 2008.

- ^ Chiasson 2011.

- ^ Ashbery et al. n.d.

- ^ a b Lewallen 2001, p. 1.

- ^ Brainard & Dlugos 1980, p. 35.

- ^ Lewallen 2001, p. 136.

- ^ Caples 2001.

- ^ Lewallen 2001, pp. 59, 136–137.

- ^ a b Ashbery & Labrie 1984, p. 33.

- ^ Baumbach et al. 1975, p. 18.

- ^ a b Lewallen 2001, p. 26.

- ^ Diggory et al. 2009, p. 487.

- ^ a b Lewallen 2001, pp. 26, 103.

- ^ Kermani 1976, p. 91.

- ^ Kermani 1976, p. 33; Baumbach et al. 1975, pp. 7–8 (statement by Ronald Sukenick describing the aims of the Fiction Collective), 18–27 ("From The Vermont Notebook").

- ^ Baumbach et al. 1975, p. 18; Kermani 1976, p. 33.

- ^ a b Kermani 1976, p. 33.

- ^ Kermani 1976, p. 34.

- ^ Publishers Weekly 2001.

- ^ a b c d Boening 2003, p. 111.

- ^ a b Schmidt 2014, p. 61.

- ^ The Massachusetts Review n.d.; Ashbery & Brainard 2008, pp. 22–25.

- ^ Rosenbaum 2013, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Rosenbaum 2013, p. 59.

- ^ Shapiro 2007, p. 310.

- ^ a b Shoptaw 1994, p. 16.

- ^ Shoptaw 1994, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Wasley 2002, p. 689.

- ^ Schmidt 2014, p. 63.

- ^ Wasley 2002, pp. 688–689.

- ^ Ward 2001, p. 85; Rosenbaum 2013, p. 59.

- ^ Levy 2011, p. 198.

- ^ a b Shapiro 1979, p. 10.

- ^ Levy 2011, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Vincent 1998, p. 160.

- ^ Ronda 2018, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Schmidt 2014, p. 24.

- ^ a b Lewallen 2001, p. 57.

- ^ Pardlo 2012, p. 588.

- ^ Kernan 1997, p. 39; Kernan 2001, p. 323.

- ^ Diggory et al. 2009, p. 488.

- ^ Levy 2011, p. 170.

- ^ Silliman 2007, p. 287. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSilliman2007 (help)

- ^ Silliman 2007, pp. 287–288. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSilliman2007 (help)

- ^ Silliman 2007, p. 297. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSilliman2007 (help)

- ^ Ward 2001, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Schmidt 2014, p. 58.

- ^ Shoptaw 1994, p. 14 (cited by Levy 2011, p. 170; Rosenbaum 2013, p. 60; and Schmidt 2014, p. 58).

- ^ Bromwich 1975, p. 975.

Sources[edit]

- Anon. (n.d.). "Table of Contents 2000–2009". The Massachusetts Review. Archived from the original on March 20, 2017.

- Anon. (2001). "Review: The Vermont Notebook". Publishers Weekly. Archived from the original on October 23, 2019.

- Ashbery, John; et al. (n.d.). "Critics". JoeBrainard.org. Ron Padgett and the Estate of Joe Brainard. Archived from the original on December 7, 2018.

- Ashbery, John; Brainard, Joe (Spring–Summer 2008). "From The Vermont Notebook". The Massachusetts Review. 49 (1–2): 22–25. JSTOR 25091272.

- Ashbery, John; Labrie, Ross (May–June 1984). "John Ashbery: An Interview by Ross Labrie". The American Poetry Review. 13 (3): 29–33. JSTOR 27777370.

- Baumbach, Jonathan; et al., eds. (1975). Statements: New Fiction from the Fiction Collective. George Braziller, Inc. ISBN 0-8076-0778-9 – via the Internet Archive (registration required).

- Boening, John (April–June 2003). "Reviewed Work: The Vermont Notebook by John Ashbery, Joe Brainard". World Literature Today. 77 (1). University of Oklahoma: 111. doi:10.2307/40157859. JSTOR 40157859.

- Brainard, Joe; Dlugos, Tim (1980). "The Joe Brainard Interview [September 26, 1977]" (PDF). Little Caesar (10): 24–39. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 7, 2018 – via CuneiformPress.com.

- Bromwich, David (Winter 1975). "Reviewed Works: Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror by John Ashbery; Resident Alien by Daryl Hine, John Hollander; Tales Told of the Fathers by John Hollander". The Georgia Review. 29 (4). University of Georgia: 975–983. JSTOR 41399568.

- Caples, Garrett (February 2001). "Joe Brainard: A Retrospective – Berkeley Art Museum through May 27". ReviewWest.com. Archived from the original on August 23, 2016 – via GranaryBooks.com.

- Chiasson, Dan (February 26, 2011). "'A Vanguard of Friends'". The New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on July 10, 2019.

- Cotter, Holland (September 12, 2008). "The Poetry of Scissors and Glue". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 30, 2018.

- Deming, Richard (2008). "Everyday Devotions: The Art of Joe Brainard". Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin. Yale University Art Gallery: 75–87. JSTOR 40514715.

- Diggory, Mark; et al., eds. (2009). Encyclopedia of the New York School Poets. Facts on File, Inc. (an imprint of Infobase Publishing). ISBN 978-0-8160-5743-6 – via Google Books.

{{cite book}}:|editor2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: editors list (link) - Kermani, David K. (1976). John Ashbery: A Comprehensive Bibliography, Including His Art Criticism, and with Selected Notes from Unpublished Materials. Garland Reference Library of the Humanities. Vol. Vol. 14. Garland Publishing. ISBN 0-8240-9997-4 – via the Internet Archive (registration required).

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Kernan, Nathan (March–April 1997). "Joe Brainard: All Possible Colors". On Paper. 1 (4). Art in Print: 36–40. JSTOR 24554550.

- ——— (May 2001). "Joe Brainard. Berkeley". The Burlington Magazine. 143 (1178): 321–323. JSTOR 889159.

- Lewallen, Constance M. (2001). Joe Brainard: A Retrospective. With essays by John Ashbery and Carter Ratcliff. The Berkeley Art Museum at the University of California, Berkeley and Granary Books. ISBN 1-887123-44-X – via the Internet Archive (registration required).

- Levy, Ellen (2011). Criminal Ingenuity: Moore, Cornell, Ashbery, and the Struggle Between the Arts. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-974635-4 – via Google Books.

- Pardlo, Gregory (Summer 2012). "Node 5: Ekphrasis and the Question of Perfect Equilibrium". Callaloo. 35 (3). Johns Hopkins University Press: 584–603. doi:10.1353/cal.2012.0094. JSTOR 23274330.

- Pritchard, William H. (Autumn 1976). "Reviews: More Poetry Matters". The Hudson Review. 29 (3): 453–463. doi:10.2307/3850304. JSTOR 3850304.

- Rosenbaum, Susan (2013). "'Permeation, Ventilation, Occlusion': Reading John Ashbery and Joe Brainard's The Vermont Notebook in the Tradition of Surrealist Collaboration". In Silverberg, Mark (ed.). New York School Collaborations: The Color of Vowels. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 59–90. ISBN 978-1-137-28056-5.

- Schmidt, Christopher (2014). The Poetics of Waste: Queer Excess in Stein, Ashbery, Schuyler, and Goldsmith. Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9781137402790. ISBN 978-1-137-40278-3.

- Shoptaw, John (1994). On the Outside Looking Out: John Ashbery's Poetry. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63612-0.

- Shapiro, David (2007). "A Birthday Notebook for JA: The Vermont Notebook (1975)". Conjunctions (49). Bard College: 302–310. JSTOR 24516476.

- Silliman, Ron (2007). "Four Contexts for Three Poems: Three Poems (1972)". Conjunctions (49). Bard College: 283–301. JSTOR 24516475. See also: Silliman, Ron (August 10, 2007). "Untitled post ["To ask what makes John Ashbery a New American Poet..."]". Silliman's Blog. Archived from the original on September 26, 2017 – via Blogger.

- Vincent, John (Summer 1998). "Reports of Looting and Insane Buggery Behind Altars: John Ashbery's Queer Poetics". Twentieth Century Literature. 44 (2). Duke University Press: 155–175. doi:10.2307/441869. JSTOR 441869.

- Ward, Geoff (2001) [1st. ed. 1993]. Statutes of Liberty: The New York School of Poets (2nd ed.). Palgrave. doi:10.1057/9780230372771. ISBN 978-0-230-37277-1.

- Wasley, Aidan (Winter 2002). "The 'Gay Apprentice': Ashbery, Auden, and a Portrait of the Artist as a Young Critic". Contemporary Literature. 43 (4). University of Wisconsin Press: 667–708. doi:10.2307/1209038. JSTOR 1209038.

Category:1975 books

Category:1975 poems

Category:English-language books

Category:Poems in English

Category:Experimental literature

Category:Fine illustrated books

Category:1970s LGBT literature

Category:LGBT poetry

Category:Literary collaborations

Category:Poetry by John Ashbery

Category:New England in fiction