User:Cdjp1/sandbox/seacadet

Dutch conquest of the Banda Islands[edit]

| Dutch conquest of the Banda Islands | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the European colonization of Asia | |||||||

Dutch map of the Banda Islands, dated c. 1599–1619 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Supported by: Japanese mercenaries |

Bandanese fighters Supported by:[1] | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Pieter Willemsz. Verhoeff Piet Hein Gerard Reynst Jan Dirkszoon Lam Jan Pieterszoon Coen | Unknown | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown. Total population including civilians estimated 15,000[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | c. 14,000 dead, enslaved or fled elsewhere[3][2] | ||||||

The Dutch conquest of the Banda Islands was a process of military conquest from 1609 to 1621 by the Dutch East India Company of the Banda Islands. The Dutch, having enforced a monopoly on the highly lucrative nutmeg production from the islands, were impatient with Bandanese resistance to Dutch instructions that the Bandanese sell only to them. The Dutch used the death of a Dutch official as a casus belli for a forcible conquest of the islands. The islands became severely depopulated as a result of the massacres and forced deportations by the Dutch.

The Dutch East India Company, which was founded in 1602 as an amalgamation of 12 voorcompagnies, had extensive financial interests in maritime Southeast Asia, the source of highly profitable spices which were in high demand in Europe. A Dutch expedition had already made contact with the islands in 1599, signing several contracts with Bandanese chiefs. The profitability of the spices was heightened by the fact that they grew nowhere else on Earth, making them extremely valuable to whoever controlled them. As the Dutch attempted to form a monopoly over the spices and forbid the Bandanese from selling to any other group, they resisted, and the Dutch decided to conquer the islands by force. With the aid of Japanese mercenaries, the Dutch launched several military expeditions against the Bandanese.

The conquest culminated in the Banda massacre, which saw 2,800 Bandanese killed and 1,700 enslaved by the Dutch. Along with starvation and constant fighting, the Bandanese felt they could not continue to resist the Dutch and negotiated a surrender in 1621. Jan Pieterszoon Coen, the official in charge of the fighting, expelled the remaining 1,000 Bandanese to Batavia. With the Bandanese resistance ended, the Dutch secured their valuable monopoly on the spice trade.

Background[edit]

The first Dutch expedition to explore the Banda Islands, as well as Banten, Ternate and Ambon, was launched by a voorcompagnie on 1 May 1598. A fleet commanded by Jacob Corneliszoon van Neck, Jacob van Heemskerck and Wybrand van Warwijck set sail and made contact with the inhabitants of the Banda Islands in 1599. Heemskerck signed several contracts with Bandanese chieftains and constructed a spice trading outpost.[4] The volcanic Banda Islands were found to be unique due to the availability of nutmeg and mace, which grew nowhere else in the world and therefore had extreme commercial value.[1]

Early trade and conflicts[edit]

Battle of Banda Neira[edit]

The Dutch East India Company (known by its Dutch acronym, VOC) was founded on 20 March 1602 as a merger of the twelve voorcompagnieën, with the exclusive right to all Dutch navigation and trade in Asia and the East Indies, including the right to conclude treaties, declare and wage war, and establish fortresses and trading posts.[5] In early April 1609, a Dutch fleet commanded by Pieter Willemsz. Verhoeff arrived at Banda Neira and wanted to force the establishment of a fortress. The Bandanese preferred free trade so that they could play off the various European countries' merchants against each other and sell their products to the highest bidder.[6] However, the Dutch sought to establish a monopoly on the spice trade so that the Bandanese could sell their products only to the Dutch.[1] Negotiations were arduous, and at a certain point in late May 1609, the chieftains lured Verhoeff and two other commanders who had left their fleet to negotiate on the beach, into the woods into an ambush and killed them.[1] Their guard was also massacred by the Bandanese, so that a total of 46 Dutchmen were killed.[7] In retaliation, the Dutch soldiers plundered several Bandanese villages and destroyed their boats.[1] In August, a peace favourable to the Dutch was signed: the Bandanese recognised Dutch authority and monopoly on the spice trade.[1] That same year, Fort Nassau was built on Banda Neira to control the nutmeg trade.[8][9]

Expeditions against Lontor, Run and Ai[edit]

Piet Hein replaced Verhoeff as the fleet's commander. Having finished constructing Fort Nassau, the fleet sailed north to Ternate, whose sultan allowed the Dutch to rebuild an old damaged Malay fortress that was renamed Fort Oranje in 1609.[1] This became the de facto capital of the Dutch East India Company until Batavia (modern-day Jakarta) was founded on Java in 1619. The Dutch got involved in a brief war between Ternate and the nearby island kingdom of Tidore.[1] In March 1610, Hein arrived on Ambon and, after long but ultimately successful trade negotiations on a large clove purchase with the Ambonese from March to November 1610,[1] he conducted two punitive military expeditions in early 1611 against the Bandanese isles of Lontor (also known as Lontar or Banda Besar) and Pulo Run.[1] Thereafter, he was tasked to build Fort Belgica on Banda Neira, which became the third Dutch fortress on the Banda Islands.[1] A 1610 Dutch attack on island of Ai, however, proved to be a failure.[7]

Conquest of Ai[edit]

The Bandanese resented the violently imposed obligation to trade exclusively with the Dutch. They violated their treaty with the Dutch by trading with the English (who offered better prices), and Malay, Javanese and Makassarese traders (who sold the spices on to the Portuguese).[10] Unable to accept this intrusion in their commercial interests any longer, the VOC's governing body, Heeren XVII, concluded by 1614 that it was necessary to conquer the entire Bandanese archipelago, even if it meant the destruction of the native population and a heavy burden on the Company's finances.[7] To that end, Governor-General Gerard Reynst took an army to Banda Neira on 21 March 1615, and then launched a punitive expedition against the island of Ai (or Pulu Ay) on 14 May 1615. The natives' fortresses were initially successfully attacked, but the Dutch troops resorted to plundering too early.[10] The English, who had retreated to Run, regrouped and launched a surprise counterattack that same night in which they managed to kill 200 Dutchmen.[11] Reynst decided to withdraw from Ai, intending to conquer the island later and first preventing the English from obtaining clove at Ambon, but he died of illness in December 1615.[10]

Meanwhile, the Bandanese beseeched the English for protection against possible Dutch retaliation, sending an emissary to the English factory at Banten with a letter, which included the following statements:

Therefore we all desire to come to an agreement with the kinge of England, because nowe the Hollanders doe practise by all meanes possible to conquer our Country and destroy our Religion by reason whereof all of us of the Islands of Banda do utterly hate the sight of theis Hollanders, sonnes of Whores, because they exceed in lying and villainy and desire to overcome all mens Country by Treachery... That if soe be the Kinge of England out of his love towards us will have a care of our Country and Religion and will help us with Artillary powder and shott and help us recover the Castle of Nera, whereby we may be able to make war with the Hollanders, by Gods helpe all the spices, that our land shall yeald, we will sell only to the King of England.[11]

In April 1616, Jan Dirkszoon Lam took 263 men with him and, against fierce resistance, was able to conquer Ai. Lam decided to make an example of the island, killing any native who put up resistance, while another 400 natives (amongst whom were many women and children) drowned while trying to flee to the nearby English-controlled island of Run in the west.[7][12] This forced the orang kaya on the other Banda Islands once more to sign contracts favourable to the Dutch. Lam ordered the construction of Fort der Wrake (named Fort Revenge by the English) on Ai to emphasise the brutal vengeance the Bandanese should expect to suffer if they broke trade deals with the Dutch. However, even these actions proved to be insufficient to allow the Dutch to form a monopoly over the nutmeg and mace trade.[12] Although initially intimidated, the Lontorese soon resumed trading with former trade partners, including the English, who had established themselves on the islands of Run and Nailaka.[7]

Siege of Run[edit]

On 25 December 1616, English merchant-adventurer Nathaniel Courthope landed of the island of Run with 39 men and constructed a fortress on it. He persuaded the inhabitants to sign a contract in which they undertook to accept King James I as the sovereign of the island and to provide the English with nutmeg. The Dutch proceeded to lay siege to the English fortress, which with native assistance managed to resist them for over four years, with the fortress finally falling to the Dutch after Courthope was killed in a skirmish, causing the English to abandon the island.[13][11] Finally in possession of Run, the Dutch proceeded to kill or enslave all adult men, exile the women and children and chop down every nutmeg tree on the island to make it useless should the English try to re-establish trade on the island.[11][2] The Dutch allowed some cattle to roam free on Run, in order to provide food for the other islands.[14] It was not until 1638 that the English tried to visit Run again, after which Dutch officials annually visited the island to check if they had secretly re-established themselves until the English formally renounced all claims to the Banda Islands in 1667.[14]

Anglo–Dutch conflicts[edit]

While the siege of Run was ongoing, tensions between the Dutch East India Company and the English East India Company rose and erupted in open naval warfare in 1618. The new VOC Governor-General Jan Pieterszoon Coen wrote a letter, now known as the Appeal of Coen, to the Heeren XVII on 29 September 1618, requesting more soldiers, money, ships and other necessities in order to wage war against both the Bandanese and the English. Being a pious Calvinist, he tried to persuade his superiors that it would be a good investment they would not regret, because the Christian god would support them and bring victory, despite earlier setbacks: 'Despair not, spare not your enemies, there is nothing in the world that can hinder or harm us, for God is with us, and do not draw a conclusion from the preceding failures, because there, in the Indies, something grand can be accomplished.'[15]

The Dutch managed to seize eleven English ships, some of which were carrying cargoes of silver, while the English captured only one Dutch ship. However, this unofficial war was inopportune to the governments back in Europe, who in 1619 concluded peace and a Treaty of Defence between the Dutch Republic and England, as they prioritised a Protestant alliance against Catholic Spain and Portugal with the end of the Twelve Years' Truce nearing. The Heeren XVII ordered Coen to cease hostilities, and cooperate with the English, who would receive one-third of all spices from the Spice Islands and the Dutch the other two-thirds.[11] Coen was furious with the instructions when he received them, as he sought to expel the English from the entire region to form a monopoly on the spice trade, as he wrote to his superiors in a letter:

I admit that the actions of the master are of no concern of the servant... But under correction Your Honours have been too hasty. The English owe you a debt of gratitude, because after they have worked themselves out of the Indies, your Lordships put them right back again... it is incomprehensible that the English should be allowed one third of the cloves, nutmegs and mace, for they cannot lay claim to a single grain of sand in the Moluccas, Amboyna or Banda.[11][note 1]

Banda massacre[edit]

| Banda Massacre | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Dutch conquest of the Banda Islands | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Bandanese fighters | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Jan Pieterszoon Coen | Unknown | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

2,000 combatants[14] 2,500–3,000 civilians[17] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| |||||||

Judging that Bandanese resistance to Dutch attempts to establish their commercial supremacy in the archipelago had to be crushed once and for all, Coen wrote a letter to the Heeren XVII on 26 October 1620, stating: 'To adequately deal with this matter, it is necessary to once again subjugate Banda, and populate it with other people.'[17] As proposed, the Heeren XVII instructed him to subjugate the Bandanese and drive their leaders out of the land.[11]

Invasion[edit]

The Dutch fleet from Batavia sailed at the end of 1620.[2] It first arrived at Ambon, where it joined with reinforcements in the form of soldiers and ships before continuing to Banda.[11] The fleet consisted of 19 ships, 1,655 Dutch soldiers and 286 Japanese mercenaries, and was personally led by Coen himself.[2] On 21 February 1621, the fleet arrived in Fort Nassau, where it was reinforced by the fort's 250-strong garrison and 36 native ships.[18]

After unsuccessfully trying to recruit Englishmen from the nearby Run and Ai, Coen began sending scouts to the coastline of Lontor, the main Bandanese island. The reconnaissance took two days, during which some boats came under cannon fire from the Bandanese defenders. The scouts found fortified positions along the southern coast and in the hills and failed to find a possible beachhead. On 7 March, a Dutch probing party landed on the island but was repulsed after suffering one man killed and four wounded.[19]

On 11 March, Coen ordered an all-out offensive. He divided his forces into several groups, which attacked different points on the island. The Dutch swiftly captured key strongholds and by the end of the day the island's northern lowlands and southern promontories. The defenders and local populace fled to the hills that made up the island's center, with the Dutch forces in hot pursuit. By the end of 12 March, the Dutch occupied the whole island, suffering 6 killed and 27 wounded.[20]

Temporary peace[edit]

After the Dutch initial success, Lontor's upper class (the orang kaya) sought peace. They offered gifts to Coen and accepted all of the Dutch demands. They agreed to surrender their weapons, destroy their fortifications, and release any hostages they had captured. They accepted the VOC's sovereignty and the construction of several Dutch fortresses on the island, promised to pay a portion of their spice harvest, and sell the remainder exclusively to the Dutch at a fixed price. In exchange, the Dutch agreed to give the natives personal freedom, autonomy and the right to keep practicing Islam.[21][2][17]

Resumption of hostilities and massacre[edit]

As peace was agreed between the orang kaya and the Dutch, most of the islanders fled to the hills and began to engage in skirmishes with the Dutch. Coen responded by razing villages and forcing their inhabitants to work for the Dutch.[21]

On 21 April, by means of torture, the Dutch extracted confessions from the orang kaya about a conspiracy against them.[22] Coen captured at least 789 orang kaya along with their family members and deported them to Batavia, where many were enslaved.[3][2] Having been accused of breaking the treaty and conspiring against the Dutch, 24 orang kaya were sentenced to death and decapitated by Japanese mercenaries on 8 May.[17] The executions did not quell native resistance, however,[17] so Coen ordered his troops to sweep the island and to destroy its villages in order to force the surrender of the population.[3] The next few months the Dutch and the natives were engaged in fierce fighting. Witnessing the destruction caused by the Dutch, many natives chose to die of starvation or from jumping off the cliffs rather than surrender.[2]

Aftermath[edit]

According to Coen, "about 2,500" inhabitants died "of hunger and misery or by the sword", "a good party of woman and children" were taken, and not more than 300 escaped.[3] Hans Straver concluded that the Lontorese population would have been around 4,500–5,000 people, 50 to 100 of whom died during the fighting, 1,700 of whom were enslaved and 2,500 of whom died due to famine and disease, while an unknown number of natives jumped to their deaths from the cliffs; several hundreds escaped to nearby islands such as the Kei Islands and eastern Seram, their regional trading partners, that welcomed the survivors.[17]

After the campaign, the Dutch controlled virtually all of the Banda Islands. The English had already abandoned Run, and had an only intermittent presence on Nailaka. By signing the 1667 Treaty of Breda, the English formally relinquished their claim to the islands.[14] The islands were severely depopulated as a result of the campaign. American historians Vincent Loth and Charles Corn estimated that the entire population of the Banda Islands before the conquest had been around 15,000 people, of whom only 1,000 survived the conquest including those who lived in or fled to the English-controlled islands of Ai and Run.[3][2] Peter Lape estimated that 90% of the population was killed, enslaved or deported during the conquest.[23]

To keep the archipelago productive, the Dutch repopulated the islands, mostly with slaves taken from the Dutch East Indies, India and China, working under command of Dutch planters (perkeniers).[24] The original natives were also enslaved and were ordered to teach the new arrivals about nutmeg and mace production.[25] The treatment of the slaves was severe—the native Bandanese population dropped to 100 by 1681, and 200 slaves were imported annually to keep the slave population at a total of 4,000.[25] Although the Dutch did not regard the Christianisation of their slaves as a priority, they forced all Europeans on the Banda Islands to convert and adhere to the Dutch Reformed Church (a form of Calvinist Christianity), while Catholicism (introduced by Portuguese Jesuits in the 16th century) was forbidden and all Catholics forcibly converted. The slave population (consisting of surviving natives and imported slaves) was allowed to practice Islam or animistic faiths, but also encouraged and sometimes forcibly coerced to join the Reformed Church.[26]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ This is a selective English translation by Ian Burnet (2013) of the letter that Coen wrote on 11 May 1620 from Fort Batavia to the Heeren XVII (addressed as U Ed., meaning "You Nobles"). Burnet's translation is composed from the following fragment: 'Lachen d'Engelsen tot danckbaerheyt, soo is den arbeyt niet verlooren. Grooten danck zyn zy U Ed. schuldich, want hadden haer selven met recht uyt Indien geholpen en de Heeren hebben hun daer weder midden in geseth. Meenen zy 't recht en wel, 'tsal wel wesen, maer wederom quaet willende hebt ghylieden, is het te duchten, 't serpent in den boesem geseth. Wy bekennen, dat het den knecht niet en roert, wat de meester doet, maer evenwel doet ons het gemeen gebreck, gelyck de zotten, spreecken, niet om dese vereeninge te bestraffen, want ons kennelyck is, hoeveele de staet der Vereenichde Nederlanden ten hoochsten aen de goede vrientschap, correspondentie en vereeninge van de Croone van Engelandt gelegen is; maer U Ed. zyn, onder correctie, al te haestich geweest, ende waeromme d'Engelsen een derde van de nagelen, noten en foelye vergunt is, connen niet wel begrypen; niet één sandeken van het strandt hadden zy in de Molluccos, Amboyna, noch Banda te pretendeeren.'[16] A full modern English translation of the original reads approximately: "The English are laughing out of gratitude, because now their efforts have not been in vain. They owe You Nobles great thanks, for they had just rightly helped themselves out of the Indies, but the Heeren have placed them right back in the midst of it again. If they mean right and well, then it will be well, but [if they are] willing to do evil again, it is to be feared that the serpent has been put right in front of [our] chest. We admit that what the master does is of no concern of the servant. However, our shared problem makes us speak, as the fools do, not to condemn this [peace] agreement – because we understand how important the good friendship, correspondence and association with the Crown of England is to the State of the United Netherlands. But You Nobles have, under correction, been too hasty, and it cannot be well understood why the English should be allowed one third of the cloves, nutmegs and mace; [at the time the peace treaty was signed,] they could not lay claim to [even] a single grain of sand from the beaches in the Moluccas, Amboyna, or Banda.'

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Rozendaal, Simon (2019). Zijn naam is klein: Piet Hein en het omstreden verleden (in Dutch). Amsterdam: Atlas Contact. pp. 126–130. ISBN 9789045038797. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Loth 1995, p. 18.

- ^ a b c d e Corn 1998, p. 170.

- ^ Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "Banda-eilanden. §1. Geschiedenis", "Heemskerck, Jacob van". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- ^ Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie. §1. Ontstaansgeschiedenis". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- ^ Dillen, J.G. van (1970) Van rijkdom en regenten, p. 128–129.

- ^ a b c d e Loth 1995, p. 17.

- ^ Hanna, Willard A. (1991). Indonesian Banda. Banda Neira: Yayasan Warisan dan Budaya Banda Neira. p. 27.

- ^ Milton, Giles (1999). Nathaniel's Nutmeg. London: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 3.

- ^ a b c Molhuysen, Philipp Christiaan; Blok, Petrus Johannes (1918). "Reijnst". Nieuw Nederlandsch Biografisch Woordenboek (in Dutch). Leiden: A.W. Sijthoff. pp. 1147–1148. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Burnet, Ian (2013). East Indies. Sydney: Rosenberg Publishing. pp. 102–106. ISBN 9781922013873. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ a b den Heijer, Henk (2006). Expeditie naar de Goudkust: Het journaal van Jan Dircksz Lam over de Nederlandse aanval op Elmina, 1624-1626 (in Dutch). Zutphen: Walburg Pers. p. 45. ISBN 9789057304453. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- ^ Ratnikas, Algirdas J. "Timeline Indonesia". Timelines.ws. Archived from the original on 10 July 2010. Retrieved 2010-08-12.

- ^ a b c d Loth 1995, p. 19.

- ^ Joustra, Arendo, ed. (2005). Erfgoed: de Nederlandse geschiedenis in 100 documenten (in Dutch). Amsterdam: Elsevier. p. 47. ISBN 9789068823400. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ De Opkomst van het Nederlandsch gezag in Oost-Indië (1869), p. 204.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Straver, Hans (2018). Vaders en dochters: Molukse historie in de Nederlandse literatuur van de negentiende eeuw en haar weerklank in Indonesië (in Dutch). Hilversum: Uitgeverij Verloren. pp. 90–91. ISBN 9789087047023. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

Om hierin naar behooren te voorzien is het noodig dat Banda t'eenemaal vermeesterd en met ander volk gepeupleerd worde.

- ^ Corn 1998, p. 165.

- ^ Corn 1998, pp. 165–66.

- ^ Corn 1998, p. 166.

- ^ a b Corn 1998, p. 167.

- ^ Corn 1998, p. 169.

- ^ Lape 2000, p. 139.

- ^ Loth 1995, p. 24.

- ^ a b Van Zanden 1993, p. 77.

- ^ Loth 1995, p. 27–28.

Bibliography[edit]

- Corn, Charles (1998). The Scents of Eden: A Narrative of the Spice Trade. New York City: Kodansha International. ISBN 9781568362021.

- Hanna, Willard A. (1978). Indonesian Banda: Colonialism and Its Aftermath in the Nutmeg Islands. Philadelphia: Institute for the Study of Human Issues. ISBN 9780915980918.

- Lape, Peter V. (2000). "Political Dynamics and Religious Change in the Late Pre–Colonial Banda Islands, Eastern Indonesia". World Archaeology. 32 (1). Taylor & Francis: 138–155. doi:10.1080/004382400409934. JSTOR 125051. S2CID 19503031.

- Loth, Vincent C. (1995). "Pioneers and Perkeniers: The Banda Islands in the 17th Century". Cakalele. 6. Honolulu: University of Hawaii at Manoa: 13–35. hdl:10125/4207.

- Van Zanden, J. L. (1993). The Rise and Decline of Holland's Economy: Merchant Capitalism and the Labour Market. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719038068.

Further reading[edit]

- Ghosh, Amitav (2021). The Nutmeg's Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 1529369479.

Sea Cadet[edit]

The History of Sea Cadets in the UK can be traced back to the back to the Crimean War (1854–1856) when sailors returning home from the campaign formed Naval Lads' Brigades to help orphans in the back streets of sea ports. With the first recorded Brigade being established in the Kent port of Whitstable. The success of the brigades in helping disadvantaged youth led to the formation of the Navy League, a national organisation with a membership of 250,000 dedicated to supporting the Royal Navy, which subsequently adopted the Brigades in 1910.

Timeline[edit]

1800s[edit]

The first Naval Lads' Brigade was established in Whitstable, Kent in 1856.[1][2] The Navy League was formed in London in 1895 stating its purpose as securing ‘the primary object of the national policy, The Command of the Sea’, with the foundations of the organisation appearing in the Pall Mall Gazette in 1894.[3][4][5] Queen Victoria became the patron of the Naval Lads' Brigade in 1899, and gifted the Windsor Sea Cadets unit £10 to purchase uniforms (a date which has been adopted as the official birthday of the Corps).

Early 1900s[edit]

The Royal Marines Artillery Cadet Corps (RMACC) was established in the Mission Hall, Prince Albert Street, Eastney on 14 February 1901. The new Cadet Corps was then based at the now closed Royal Marines Eastney Barracks in Portsmouth. It was formed, so the story goes, to "gainfully occupy the spare time of sons of senior Non-Commissioned Officers (SNCOs)" after an occasion when the colonel's office window was broken by a ball kicked by an SNCO's son playing outside. The Royal Naval Volunteer Cadet Corps (a separate organization to the Sea Cadets),[6] was formed in 1904 when the officer in charge of HMS Victory barracks in Portsmouth, now known as HMS Nelson, requested permission from Commander-in-Chief, Portsmouth to form a cadet corps unit similar to the Royal Marines Artillery Cadets in Eastney. The Admiralty granted permission and soon units were also established at HM Dockyard Devonport, HM Dockyard Chatham, HMS Collingwood, HMS Dryad, HMS Daedalus, HMS Dolphin HMS Excellent, HMS Sultan, and HMS Vernon. Entry was originally restricted to the sons of serving ratings but was later opened up to boys and girls from the general public, this lead to other units openening and being sponsored by Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve units.[7] The date of the request, 29 July 1904, is regarded as the birthday of the Royal Naval Cadets.[8] The Navy League sponsored some independent units as Navy League Boys' Naval Brigades beginning in 1910, this expanded later on to include Sea Scouts groups.[5][9] The Navy League applied to the Admiralty in 1914 for recognition of its 34 Boys' Naval Brigades. This was granted in 1919 subject to an annual inspections by an officer of the Admiral Commanding Reserves. The name of this units was changed to Navy League Sea Cadet Corps. The Gillingham Fair fire disaster lead to the deaths of 4 cadets of the RMACC.[10] Lord Nuffield gave £50,000 to fund the relaunch and expansion of the Sea Cadet Corps in 1937. At the start of World War II there were almost 100 Sea Cadets Units in the UK with more than 10,000 Cadets. In the 1940s the RMACC was re-titled as the Royal Marines Volunteer Boys Corps, with Girl Ambulance Corps units being established alongside RMVBC units.

In June 1940 the Navy League purchased an old sailing vessel and renamed it TS Bounty. It was fitted out to accommodate 40 Cadets. Due to a shortage of certain ratings in the Royal Navy in 1941, special three-week training courses were established to be run on board TS Bounty for Sea Cadets, to prepare them for entry into the RN. This meant a considerable saving in training time for the Admiralty.[11] HM King George VI became Admiral of the Corps in 1942, and the name Sea Cadet Corps was officially adopted. The Admiralty now paid for uniforms, equipment, travel and training, while the Navy League funded sport and Unit headquarters. An expansion of the Corps to 400 Units and 50,000 Cadets coincided with the period of Warship Weeks in many towns, leading to many newly formed units taking the same name as the adopted warship. The Admiralty now paid for uniforms, equipment, travel and training, while the Navy League funded sport and unit headquarters. In the same year, the Girls' Naval Training Corps was formed as part of the National Association of Training Corps for Girls, with units mainly in southern England.[12][11][9] By the end of World War II there were 399 Sea Cadet units affiliated with the Navy League.[9]

In 1947 the Sea Cadet Charter was signed by the Navy League and the Admiralty to continue to act as co-sponsors of the Sea Cadet Corps.[9] The Sea Cadet Council was set up in 1948 to govern the Corps, with membership from the Navy League and the Royal Navy, and a retired Captain took on the task of supervision, first as Secretary to the Council and later as Captain, Sea Cadets. Also during this year school contingents of Sea Cadet were amalgamated with the Junior Training Corps (formerly the Junior Division of the Officers Training Corps) and the school contingents of the and Air Training Corps to form the Combined Cadet Force.[13]

Late 1900s[edit]

In 1951, 24 Cadets of the RMVBC were killed and 18 injured when a double decker bus collided with them.[14] HM The Queen became Patron, and HRH the Duke of Edinburgh was made the Admiral of the Corps in 1952. By this year the Girls' Naval Training Corps was 50 Units strong and in the late 1950s changed their name to the Girls' Nautical Training Corps. The Commandant General, Royal Marines, asked permission to form a Marine Cadet Section that could be fitted into the existing organisation and the Council agreed to this. In December 1954, the first Royal Marines Cadets detachment was opened in Bristol Adventure Unit.[15]

The Girls' Nautical Training Corps became affiliated to Sea Cadets in 1963, in many cases sharing the same premises with local Sea Cadet units, such as Raven's Ait (then also known as TS Neptune). The Marine Cadets Section had expanded from the original five Detachments to 40 by 1964. TS Bermuda was established in the British colony of Bermuda in 1966. The first unit of the Bermuda Sea Cadet Corps, an offshoot of the Sea Cadet Corps with identical organisation and operations, administered by the Bermuda Sea Cadet Association. Officers of the BSCC hold honorary Royal Naval Reserve (SCC) commissions.

By the 1970s the RMVBC and Girls Ambulance Corps had been merged and renamed the Royal Marines Volunteer Cadet Corps. TS Royalist, the flagship of the Sea Cadets was commissioned in 1971. Junior Sections were introduced to the Sea Cadets in 1972. In 1976 the Navy League was renamed the Sea Cadet Association since support of the Sea Cadets and Girls’ Nautical Training Corps had become its sole aims. The admission of girls into the Sea Cadet Corps was approved in 1980, and the Girls' Nautical Training Corps was merged into the Sea Cadets and renamed as Girls' Nautical Training Contingent until 1992.[16] and the organisation was absorbed.[1][2][12]

The Duke of York was made Admiral of the Corps in 1993, and the Corps received their new Corps Colour that same year.[2] At a conference in Portsmouth in 1994 the International Sea Cadet Association was formed. The founding members were Belgium, Bermuda, Canada, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, South Africa, Sweden, the UK, and the USA.[9] The Second Sea Lord approved the change of Captain of the Sea Cadet Corps to Commodore Sea Cadet Corps, so as to bring it in to line with the other Community Cadet Forces.[2] A Centenary parade in Windsor was held in 1999, attended by HM The Queen.

2000s[edit]

In November 2004 the Sea Cadet Association merged with the charity The Marine Society to form a new umbrella charity The Marine Society & Sea Cadets, which oversees both charities.[12] The Marine Cadet Section celebrated their 50th anniversary in 2005 with a parade of 400 Cadets and Staff.[2] The Marine Cadet Section were renamed Royal Marines Cadets, following agreement by the Queen to allow the use of “Royal” in their title. An official rebadging ceremony took place at CTCRM Lympstone on 25 September 2011. The Royal Marines Cadets were inspected on parade for the first time by the Duke of Edinburgh in 2014, in his capacity as Captain General Royal Marines to mark the 350th anniversary of the Royal Marines. During this parade the Royal Marines Cadets were also joined by the RMVCC and the CCF(RM), where it was announced that all RM cadets can be title as Her Majesty's Royal Marines Cadets.[17]

Admiral of the Sea Cadet Corps[edit]

| Appointee | From | to |

|---|---|---|

| King George VI | 1942 | 1952 |

| Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh | 1952 | 1992 |

| Prince Andrew, Duke of York | 1992 | Present |

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Sea Cadet History". Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "Royal Marines History and Traditional Facts Precis Pack" (PDF). A Company. 10 October 2007. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ Johnson, Matthew (17 December 2010). "The Liberal Party and the Navy League in Britain before the Great War". Twentieth Century British History. 22 (2): 137–163. doi:10.1903. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Check|doi=value (help) - ^ a b Arnold-Baker, Charles (2007). The Companion to British History (2 ed.). Routledge. p. 922.

- ^ "Youths & Cadets". Royal Navy.

- ^ "The Navy of Civilians". The Observer. 28 June 1936. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ^ "In Pictures: HMS Victory Naval Cadets". The News.

- ^ a b c d e "History of The Sea Cadet Corps". Serious Fun. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ Time Magazine, July 22, 1929

- ^ a b "Sea Cadet History". TS Quanstock. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ a b c "2.8. A History of the Sea Cadets". Andrew Schuman - Sea Cadet Chaplains. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ The History of the Combined Cadet Force Archived 29 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine, 1260sqn.co.uk

- ^ "Cadets' Deaths – Official Inquiry to Be Held", The Times, 6 December 1951

- ^ "About us". X-Ray Company. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- ^ http://www.cardiffseacadets.co.uk/history_cadet.htm

- ^ "Royal inspection for Royal Marines Cadets". Royal Navy. 9 September 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

Wolf attack[edit]

Wolf attacks are injuries to humans or their property by any subspecies of wolf. Their frequency varies with geographical location and historical period, but overall gray wolf attacks are rare. Wolves today tend to live mostly far from people or have developed the tendency and ability to avoid them. The country with the most extensive historical records is France, where nearly 7,600 fatal attacks were documented from 1200 to 1920.[1][2] There are few historical records or modern cases of wolf attacks in North America. In the half-century up to 2002, there were eight fatal attacks in Europe and Russia, three in North America, and more than 200 in south Asia.[3] Experts categorize wolf attacks into various types, including rabies-infected, predatory, agonistic, and defensive.

Wolves and wolf–human interactions[edit]

The gray wolf is the largest wild member of the canid family, with males averaging 43–45 kg (95–99 lb), and females 36–38.5 kg (79–85 lb).[4] It is the most specialized member of its genus in the direction of carnivory and hunting large game.[5] Although they primarily target ungulates, wolves are at times versatile in their diet; for example, those in the Mediterranean region largely subsist on garbage and domestic animals.[6] They have powerful jaws and teeth and powerful bodies capable of great endurance, and often run in large packs. Nevertheless, they tend to fear and avoid human beings, especially in North America.[7] Wolves vary in temperament and their reaction to humans. Those with little prior experience with humans, and those positively conditioned through feeding, may lack fear. Wolves living in open areas, for example the North American Great Plains, historically showed little fear before the advent of firearms in the 19th century,[8] and would follow human hunters to feed on their kills, particularly bison.[9] In contrast, forest-dwelling wolves in North America were noted for shyness.[8] Wolf biologist L. David Mech hypothesized in 1998 that wolves generally avoid humans because of fear instilled by hunting.[10] Mech also noted that humans' upright posture is unlike wolves' other prey, and similar to some postures of bears, which wolves usually avoid.[7] Mech speculated that attacks are preceded by habituation to humans, while a successful outcome for the wolf may lead to repeated behavior, as documented especially in India.[10]

Categories[edit]

Rabid[edit]

Cases of rabid wolves are low when compared to other species since wolves do not serve as primary reservoirs of the disease, but can be infected with rabies from other animals such as dogs, golden jackals and foxes. Cases of rabies in wolves are very rare in North America, though numerous in the eastern Mediterranean, Middle East and Central Asia. The reason for this is unclear, though it may be connected with the presence of jackals in those areas, as jackals have been identified as primary carriers. Wolves apparently develop the "furious" phase of rabies to a very high degree, which, coupled with their size and strength, makes rabid wolves perhaps the most dangerous of rabid animals,[11] with bites from rabid wolves being 15 times more dangerous than those of rabid dogs.[12] Rabid wolves usually act alone, traveling large distances and often biting large numbers of people and domestic animals. Most rabid wolf attacks occur in the spring and autumn periods. Unlike with predatory attacks, the victims of rabid wolves are not eaten, and the attacks generally only occur on a single day.[13] Also, rabid wolves attack their victims at random, showing none of the selectivity displayed by predatory wolves, though the majority of recorded cases involve adult men, as men were frequently employed in agricultural and forestry activities which put them into contact with wolves.[14]

Non-rabid[edit]

Experts categorize non-rabid attacks based on the behavior of the victims prior to the attack and the motivations of the wolf.

Provoked[edit]

Attacks whose victims had been threatening, disciplining, disturbing, teasing, or annoying attacking wolves, their pups, families, or packs are classified as "provoked", "defensive" or "disciplinary". The attackers in such cases seem motivated, not by hunger, but fear or anger and the need to escape from or drive the victim away. Examples would include a captive wolf attacking an abusive handler; a mother wolf attacking a hiker who had wandered near her pups; an attack on a wolf hunter in active pursuit; or a wildlife photographer, park visitor, or field biologist who had gotten too close for the wolf's comfort. While such attacks may still be dangerous, they tend to be limited to quick bites and not pressed.

Unprovoked[edit]

Unprovoked attacks have been classified as "predatory"; "exploratory" or "investigative"; or "agonistic".

Predatory[edit]

Unprovoked wolf attacks motivated by hunger are categorized as "predatory". In some such cases, a cautious wolf may launch "investigative" or "exploratory" attacks to test the victim for suitability as prey. As with defensive attacks, such attacks are not always pressed, as the animal may break off the attack or be convinced to look elsewhere for its next meal.[15] In contrast, during "determined" predatory attacks, the victims may be repeatedly bitten on the head and face and dragged off and consumed, sometimes as far away as 2.5 km from the attack site, unless the wolf or wolves are driven off.[15][16] Experts in India use the term "child lifting" to describe predatory attacks in which the animal silently enters a hut while everyone is sleeping, picks up a child, often with a silencing bite to the mouth and nose, and carries a child off by the head.[16] Such attacks typically occur in local clusters, and generally do not stop until the wolves involved are eliminated.[15]

Agonistic[edit]

Agonistic attacks are motivated not by hunger nor fear but rather by aggression; designed to kill or drive off a competitor away from a territory or food source. As with predatory attacks, these may begin with or be limited to exploratory or investigative attacks designed to test the vulnerability and determination of the victim. Even when pressed until the death of the victim, agonistic attacks normally leave the victims body uneaten, at least for some time.

Factors[edit]

Habituation[edit]

Wolf attacks are more likely to happen when preceded by a long period of habituation, during which wolves gradually lose their fear of humans. This was apparent in cases involving habituated North American wolves in Algonquin Provincial Park, Vargas Island Provincial Park and Ice Bay, as well as 19th-century cases involving escaped captive wolves in Sweden and Estonia.[17][18]

Seasonality[edit]

Predatory attacks can occur at any time of the year, with a peak in the June–August period, when the chances of people entering forested areas (for livestock grazing or berry and mushroom picking) increase,[14][19] though cases of non-rabid wolf attacks in winter have been recorded in Belarus, the Kirovsk and Irkutsk districts, in Karelia, and in Ukraine.[20] Wolves with pups experience greater food stresses during this period.[14]

Victim age and sex[edit]

A worldwide 2002 study by the Norwegian Institute of Nature Research showed that 90% of victims of predatory attacks were people under the age of 18, especially under the age of 10. In the rare cases where adults were killed, the victims were almost always women. This is consistent with wolf hunting strategies, wherein the weakest and most vulnerable categories of prey are targeted.[14] Aside from their physical weakness, children were historically more vulnerable to wolves as they were more likely to enter forests unattended to pick berries and mushrooms, as well as tend and watch over cattle and sheep on pastures.[19][21][22] While these practices have largely died out in Europe, they are still the case in India, where numerous attacks have been recorded in recent decades.[21] Further reason for the vulnerability of children is the fact that some may mistake wolves for dogs and thus approach them.[22]

Wild vs. captive[edit]

Experts may distinguish between captive and wild wolf attacks, the former referring to attacks by wolves, while still of course wild animals, are kept in captivity, perhaps as pets, in zoos, or similar situations.

History and perception worldwide[edit]

Europe[edit]

In France, historical records compiled by rural historian Jean-Marc Moriceau indicate that during the period 1362–1918, nearly 7,600 people were killed by wolves, of whom 4,600 were killed by non-rabid wolves.[1] However, the zoologist Karl-Hans Taake found evidence that many of the alleged French wolf attacks occurring during the reigns of Louis XIV and Louis XV were actually carried out by big carnivores of other species which had escaped from captivity.[24][25] Numerous attacks occurred in Germany during the 17th century after the Thirty Years' War, though the majority probably involved rabid wolves.[26] Although Italy has no records of wolf attacks after WWII and the eradication of rabies in the 1960s,[26] historians examining church and administrative records from northern Italy's central Po Valley region (which includes a part of modern-day Switzerland) found 440 cases of wolves attacking people between the 15th and 19th centuries. The 19th-century records show that between 1801 and 1825, there were 112 attacks, 77 of which resulted in death. Of these cases, only five were attributed to rabid animals.[23] In Latvia, records of rabid wolf attacks go back two centuries. At least 72 people were bitten between 1992 and 2000. Similarly, in Lithuania, attacks by rabid wolves have continued to the present day, with 22 people having been bitten between 1989 and 2001.[27] Around 82 people were bitten by rabid wolves in Estonia during the 18th to 19th centuries, with a further 136 people being killed in the same period by non-rabid wolves, though it is likely that the animals involved in the latter cases were a combination of wolf-dog hybrids and escaped captive wolves.[28][29]

Russia and the Soviet Union[edit]

As with North American scientists later on (see below), several Russian zoologists after the October Revolution cast doubt on the veracity of records involving wolf-caused deaths. Prominent among them was zoologist Petr Aleksandrovich Manteifel, who initially regarded all cases as either fiction or the work of rabid animals. His writings were widely accepted among Russian zoological circles, though he subsequently changed his stance when he was given the task of heading a special commission after World War II investigating wolf attacks throughout the Soviet Union, which had increased during the war years. A report was presented in November 1947 describing numerous attacks, including ones perpetrated by apparently healthy animals, and gave recommendations on how to better defend against them. The Soviet authorities prevented the document from reaching both the public and those who would otherwise be assigned to deal with the problem.[30] All mention of wolf attacks was subsequently censored.[31]

Asia[edit]

In Iran, 98 attacks were recorded in 1981,[16] and 329 people were given treatment for rabid wolf bites in 1996.[32] Records of wolf attacks in India began to be kept during the British colonial administration in the 19th century.[33] In 1875, more people were killed by wolves than tigers, with the worst affected areas being the North West Provinces and Bihar. In the former area, 721 people were killed by wolves in 1876, while in Bihar, the majority of the 185 recorded deaths at the time occurred mostly in the Patna and Bghalpur Divisions.[34] In the United Provinces, 624 people were killed by wolves in 1878, with 14 being killed during the same period in Bengal. In Hazaribagh, Bihar, 115 children were killed between 1910 and 1915, with 122 killed and 100 injured in the same area between 1980 and 1986. Between April 1989 to March 1995, wolves killed 92 people in southern Bihar, accounting for 23% of 390 large mammal attacks on humans in the area at that time.[16][35] Police records collected from Korean mining communities during Japanese rule indicate that wolves attacked 48 people in 1928, more than those claimed by boars, bears, leopards and tigers combined.[36]

North America[edit]

There are no written records prior to the European colonization of the Americas. The oral history of some Indigenous American tribes confirms that wolves did kill humans. Tribes living in woodlands feared wolves more than their tundra-dwelling counterparts, as they could encounter wolves suddenly and at close quarters.[37] Skepticism among North American scientists over the alleged ferocity of wolves began when Canadian biologist Doug Clarke investigated historical wolf attacks in Europe and, based on his own experiences with the (as perceived by him) relatively timid wolves of the Canadian wilderness, concluded that all historical attacks were perpetrated by rabid animals, and that healthy wolves posed no threat to humans.[38] His findings are criticized for failing to distinguish between rabid and predatory attacks, and the fact that the historical literature contained instances of people surviving the attacks at a time when there was no rabies vaccine. His conclusions received some limited support by biologists but were never adopted by United States Fish and Wildlife Service or any other official organisations. This view is not taught in wolf management programs. United States Fish and Wildlife Service concludes that wolves are very shy of humans but are opportunistic hunters and will attack humans if the opportunity arises and advise against "actions that encourage wolves to spend time near people".[39] Mr Clarke's view did, however, gain popularity among laypeople and animal rights activists with the publication of Farley Mowat's semi-fictional 1963 book Never Cry Wolf,[31] with the language barrier hindering the collection of further data on wolf attacks elsewhere.[40] Although some North American biologists were aware of wolf attacks in Eurasia, they dismissed them as irrelevant to North American wolves.[7]

Wolf numbers consistently dropped across the US during the 20th century and by the 1970s they were only significantly present in Minnesota and Alaska (though in greatly reduced populations than prior to the European colonization of the Americas[41]). The resulting decrease in human-wolf and livestock–wolf interactions helped contribute to a view of wolves as not dangerous to humans. By the 1970s, the pro-wolf lobby aimed to change public attitudes towards wolves, with the phrase "there has never been a documented case of a healthy wild wolf attacking a human in North America" (or variations thereof[a]) becoming a slogan for people seeking to create a more positive image for the wolf. Several non-fatal attacks including the April 26, 2000, attack on a 6-year-old boy in Icy Bay, Alaska, seriously challenged the assumption that healthy wild wolves were harmless. The event was considered unusual and was reported in newspapers throughout the entire United States.[18][45] Following the Icy Bay incident, biologist Mark E. McNay compiled a record of wolf-human encounters in Canada and Alaska from 1915 to 2001. Of the 80 described encounters, 39 involved aggressive behavior from apparently healthy wolves and 12 from animals confirmed to be rabid.[46]

The first fatal attack in the 21st century occurred on November 8, 2005, when a young man was killed by wolves that had been habituated to people in Points North Landing, Saskatchewan, Canada[47] while on March 8, 2010, a young woman was killed while jogging near Chignik, Alaska.[48]

Notable cases[edit]

- Beast of Gévaudan (France)

- Kenton Carnegie wolf attack (Canada)

- Kirov wolf attacks (Russia)

- Patricia Wyman wolf attack (Canada)

- Wolf of Ansbach (Germany)

- Wolf of Gysinge (Sweden)

- Wolf of Soissons (France)

- Wolves of Turku (Finland)

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Other variations of the phrase include:

"There has never been a single case of a healthy wolf attacking humans in North America."[42]

"There's never been a documented case of a healthy wild wolf killing or seriously injuring a person in North America."[10]

"No healthy, wild wolf has ever killed a person in North America."[43]

"There has never been a documented case of a healthy, wild wolf killing a person in North America,"[44]

"There is no record of an unprovoked, non-rabid wolf in North America seriously injuring a person."[40]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Moriceau, Jean-Marc [in French] (2013). Sur les pas du loup: Tour de France et atlas historiques et culturels du loup, du moyen âge à nos jours [On the trail of the wolf: a tour of France and a historical and cultural atlas of the wolf, from the Middle Ages to modern times] (in French). Paris: Montbel. ISBN 978-2-35653-067-7.

- ^ Moriceau, Jean-Marc [in French] (25 June 2014). "A Debated Issue in the History of People and Wild Animals: The Wolf Threat in France from the Middle Ages to the Twentieth Century". HAL. HAL. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ Linnell et al. 2002.

- ^ Mech 1981, p. 11.

- ^ Heptner & Naumov 1998, p. 175.

- ^ Mech & Boitani 2003, p. 106.

- ^ a b c Mech, L. D.(1990) Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?, Audubon, March. (Reprinted in International Wolf 2(3):3–7.)

- ^ a b Mech & Boitani 2003, pp. 300.

- ^ Mech 1981, pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b c Mech, L. D. (1998), "Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?" -- Revisited. International Wolf 8(1): 8–11.

- ^ Linnell et al. 2002, p. 14.

- ^ Heptner & Naumov 1998, p. 267.

- ^ Linnell et al. 2002, p. 15.

- ^ a b c d Linnell et al. 2002, p. 37.

- ^ a b c Linnell et al. 2002, p. 16

- ^ a b c d Rajpurohit, K.S. 1999. "Child lifting: Wolves in Hazaribagh, India." Ambio 28(2):162–166

- ^ Linnell et al. 2002, p. 36.

- ^ a b McNay, Mark E.; Mooney, Philip W. (2005). "Attempted depredation of a child by a Gray Wolf, Canis lupus, near Icy Bay, Alaska". Canadian Field-Naturalist. 119 (2): 197–201.

- ^ a b (in Italian) Oriani, A. & Comincini, M. Morti causate dal lupo in Lombardia e nel Piemonte Orientale nel XVIII secolo, Archived 2013-11-09 at the Wayback MachineAntropofagia del Lupo nella Padania Centrale"] in atti del Seminario “Vivere la morte nel Settecento”, Santa Margherita Ligure 30 settembre - 2 ottobre 2002

- ^ Heptner & Naumov 1998, p. 268.

- ^ a b c Linnell et al. 2002, pp. 36–38.

- ^ a b Graves & Geist 2007, p. 88.

- ^ a b (in Italian) Cagnolaro, L., Comincini, M., Martinoli, A. & Oriani, A., "Dati Storici sulla Presenza e su Casi di Antropofagia del Lupo nella Padania Centrale" Archived 2013-11-09 at the Wayback Machine, in atti del convegno nazionale “Dalla parte del lupo”, Parma 9-10 ottobre 1992, Atti & Studi del WWF Italia, n ° 10, 1-160, F. Cecere (a cura di), 1996, Cogecstre Edizioni

- ^ Carnivore Attacks on Humans in Historic France and Germany: To Which Species Did the Attackers Belong? by Karl-Hans Taake. ResearchGate. 2020

- ^ Taake, Karl-Hans (2020). "Biology of the 'Beast of Gévaudan': Morphology, Habitat Use, and Hunting Behaviour of an 18th Century Man-Eating Carnivore". ResearchGate. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.17380.40328.

- ^ a b Linnell et al. 2002, p. 20.

- ^ Linnell et al. 2002, p. 21.

- ^ Linnell et al. 2002, p. 17.

- ^ Graves & Geist 2007.

- ^ Graves & Geist 2007, pp. 175–176.

- ^ a b Geist, Valerius (Summer 2009). "Let's get real: beyond wolf advocacy, toward realistic policies for carnivore conservation" (PDF). Fair Chase. pp. 26–30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 April 2016.

- ^ Linnell et al. 2002, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Linnell et al. 2002, p. 26.

- ^ Knight, J. (2003). Wildlife in Asia: Cultural Perspectives. Routledge. p. 219. ISBN 0203641817.

- ^ Jhala, Y.V. and D.K. Sharma. 1997. Child-lifting by wolves in eastern Uttar Pradesh, India. Journal of Wildlife Research 2(2):94–101

- ^ Neff, Robert, "Devils in the Darkness: The Korean Gray Wolf was a Terror for Miners" Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine, OhmyNews (June 23, 2007)

- ^ Lopez 1978, pp. 69, 123.

- ^ C. H. Doug Clarke, 1971, The beast of Gévaudan, Natural History Vol. 80 pp. 44–51 & 66–73

- ^ https://www.fws.gov/home/feature/2007/qandasgraywolfbiology.pdf Archived 2019-08-03 at the Wayback Machine [bare URL PDF]

- ^ a b Linnell et al. 2002, pp. 39–40.

- ^ "Gray Wolf Timeline for the Contiguous United States". Archived from the original on 6 June 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- ^ Parker, B. K. (1997), North American Wolves, Lerner Publications, p. 44, ISBN 1575050951

- ^ Welsbacher, A. (2001). Wolves. Capstone. p. 23. ISBN 0736807888.

- ^ Living with Wolves: Tips for avoiding Wolf Conflicts Archived 2014-01-04 at the Wayback Machine, International Wolf Center, (March 2002)

- ^ Boyd, Diane K. "(Case Study) Wolf Habituation as a Conservation Conundrum". In: Groom, M. J. et al (n.d.) Principles of Conservation Biology, 3rd ed., Sinauer Associates.

- ^ McNay, Mark E. (2002) "A Case History of Wolf-Human Encounters in Alaska and Canada", Alaska Department of Fish and Game Wildlife Technical Bulletin. Retrieved on 2013-10-09.

- ^ McNay, M. E. (2007) "A Review of Evidence and Findings Related to the Death of Kenton Carnegie on 8 November 2005 Near Points North, Saskatchewan". Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Fairbanks, Alaska.

- ^ Butler, L., B. Dale, K. Beckmen, and S. Farley. 2011.Findings Related to the March 2010 Fatal Wolf Attack near Chignik Lake, Alaska. Wildlife Special Publication, ADF&G/DWC/WSP-2011-2. Palmer, Alaska.

Bibliography[edit]

- Graves, Will N.; Geist, Valerius, eds. (2007). Wolves in Russia - Anxiety Through the Ages. Calgary, Alberta, Canada: Detselig Enterprises Ltd. ISBN 978-1-55059-332-7.

- Heptner, V. G.; Naumov, N. P. (1998). Mammals of the Soviet Union. Vol. II Part 1a, SIRENIA AND CARNIVORA (Sea cows, Wolves and Bears). Science Publishers, Inc. USA. ISBN 1-886106-81-9.

- Linnell, J. D. C.; Andersen, R. [in Norwegian]; Andersone, Z.; Balciauskas, L. [in Lithuanian]; Blanco, J.C.; Boitani, L.; Brainerd, S.; Breitenmoser, U.; Kojola, I.; Liberg, O.; Løe, J.; Okarma, H.; Pedersen, H. C.; Promberger, C.; Sand, H.; Solberg, E. J.; Valdmann, H.; Wabakken, P. (2002). The Fear of Wolves: A Review of Wolf Attacks on Humans (PDF). NINA. ISBN 978-82-426-1292-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 November 2013.

- Lopez, Barry H. (1978). Of Wolves and Men. J. M. Dent and Sons Limited. ISBN 0-7432-4936-4.

- Marvin, Garry (2012). Wolf. Reaktion Books Ldt. ISBN 978-1-86189-879-1.

- Mech, L. David (1981). The Wolf: The Ecology and Behaviour of an Endangered Species. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-1026-6.

- Mech, L. David; Boitani, Luigi (2003). Wolves: Behaviour, Ecology and Conservation. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-51696-2.

- Moriceau, Jean-Marc [in French] (2008). Histoire du méchant loup : 3 000 attaques sur l'homme en France [History of the bad wolf: 3,000 attacks on humans in France] (in French). Fayard. ISBN 978-2-213-63555-2.

Further reading[edit]

- Comincini, Mario (2002). L'uomo e la "bestia antropofaga": storia del lupo nell'Italia settentrionale dal XV al XIX secolo [Man and the "anthropophagous beast": history of the wolf in northern Italy from the 15th to the 19th century] (in Italian). Unicopoli. ISBN 978-8840007748.

- Frioux, Stephane (2009). "Review of Histoire du méchant loup: 3000 attaques de loup sur l'homme en France, XVe–XXe siècles (History of the big bad wolf: 3000 attacks on human beings in France, fifteenth–twentieth century by Jean-Marc Moriceau)". Global Environment. 3: 254–257. doi:10.3197/ge.2009.020310.

- Moriceau, Jean-Marc [in French] (2011). L'Homme contre le loup: Une guerre de deux mille ans [Man against wolf: a 2000-year war] (in French). Paris: Fayard. ISBN 2-213-63555-2.

External links[edit]

- Staying Safe in Wolf Country, ADFG (January 2009)

Roma Flag[edit]

| |

| Other names | O styago le romengo, O romanko flako |

|---|---|

| Use | Ethnic flag |

| Adopted | 1971 1978 |

| Designed by | Gheorghe A. Lăzăreanu-Lăzurică (purported) World Romani Congress Weer Rajendra Rishi |

| |

| Use | Unofficial variant |

| Adopted | 1971 |

| Designed by | Slobodan Berberski World Romani Congress |

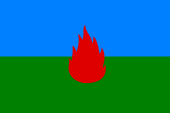

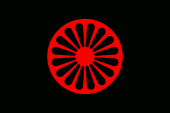

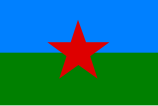

The Romani flag or the flag of the Roma (Romani: O styago le romengo, or O romanko flako) is the international ethnic flag of the Romani people, historically known as "Gypsies", which form a stateless minority in countries across Eurasia, Africa, the Americas, and Australasia. It was approved by the representatives of various Romani communities at the first and second World Romani Congresses (WRC), in 1971 and 1978. The flag consists of a background of blue and green, representing the heavens and earth, respectively; it also contains a 16-spoke red dharmachakra, or cartwheel, in the center. The latter element stands for the itinerant tradition of the Romani people and is also an homage to the flag of India, added to the flag by scholar Weer Rajendra Rishi. It superseded a number of tribal emblems and banners, several of which evoked claims of Romani descent from the Ancient Egyptians.

Older Romani symbolism comprises insignia reflecting occupational and tribal divisions, as well totems and pictograms. In some cases, Romani "Kings" and "Princes" were also integrated within the European heraldic tradition with coats of arms of their own. As a result of this synthesis, "Egyptians" became visually associated with heraldic animals, including the adder and, in the 19th century, the hedgehog. Around 1890, affiliates of the Gypsy Lore Society had deduced that a tricolor of red-yellow-black was preferred by the Spanish Romanies, and embraced it as a generic Romani symbol. In the Balkans at large, corporate representation was granted to the Gypsy esnaf—which preceded the creation of modern professional unions, all of which had their own seals or flags. The first stages of identity politics in the 20th century saw the emergence of Romani political groups, but their designs remained attached to those of more dominant cultural nationalisms in their respective country. Into the interwar era, the various and competing Romani flags were mostly based on Romanian, Polish, communist, or Islamic symbolism.

The 1971 flag claimed to revive a plain blue-green bicolor, reportedly created by activist Gheorghe A. Lăzăreanu-Lăzurică in interwar Greater Romania. This design had been endorsed in the 1950s by Ionel Rotaru, who also claimed it as a flag for an independent settlement area, or "Romanestan". A tricolor version, flown by survivors of the Romani genocide, fell out of use due to allegations that it stood for communism. Rishi's definitive variant of 1978, with the added wheel, gained in popularity over the late 20th century; it is especially associated with groups which are advocating the transnational unity of the Romani people and combating its designation as "Gypsies". This flag was promoted by actor Yul Brynner, writer Ronald Lee, and violinist Yehudi Menuhin, and it was also adopted by "King" Florin Cioabă. It was especially popular in Socialist Yugoslavia, which awarded it official recognition upon its adoption.

The WRC Congress never provided specifications for the flag, which exists in various versions and has many derivatives, including national flags defaced with Rishi's dharmachakra. Several countries and communities have officially recognized it during the 2010s, but its display has also sparked controversy in various parts of the European Union. Derivatives were also widely used in Romani political symbolism during the same period. However, inside the scholarly community, the Romani flag has been criticized as a Eurocentric symbol, and its display as a perfunctory solution to issues which are faced by the ethnic group which it represents. It has continuously been rejected by various Romani tribes, as well as by the Ashkali and Balkan Egyptians, who form a distinct ethnicity.

History[edit]

Original symbols[edit]

Scholar Konstantin Stoyanovitch notes that Romani subgroups, such as the Lovari, traditionally employed a set of quasi-heraldic symbols: "Each tribe [has] its own emblem or marking, the equivalent of a flag. This sign consists of a small piece of wood bearing some notches, or a piece of fabric or threads of various colors, or even a branch torn off the tribe's favorite tree, a tree it considered to be its own (sort of like a totem). It is only shown within the limits of a territory only used for a certain group's travels."[1] Romanies, along with the various other "traveling people" of Europe, used "rudimentary hieroglyphs" to mark their territories; art historian Amanda Wasielewski suggests that such practices survive in the "international squatters' symbol", which is indirectly based on "gypsy symbols or rogue signs".[2] Travel writer George Borrow likened the secretive tribal folklore, or "Gipsyism", to Masonic ritual and symbolism. Borrow listed tents, hammers, tongs, tin kettles, creels, and cuddies as some of the Romanies' "banners and mottoes".[3] A late-18th-century etching by Francis Wheatley shows the "genuine dwellings of English Gypsies of that date", alongside a "strange object hung on a pole". This is tentatively identified as a drag harrow, suggesting that the camp was one of "smiths, who made or repaired such tools."[4] Within Romani encampments, the usage of cloth markers extends to the practice of segregating menstruating women and their garments. Anthropologist Judith Okely proposes that "the tea towel hanging separately to dry on a line becomes a flag of ethnic purity".[5] A specific flag (steagu), fashioned from white scarf and red ribbon tied to a willow rod, appears during Gurban festival as practiced by the Boyash of Grebenac.[6]

Folklorist David MacRitchie, building on ethnological observations made Heinrich von Wlislocki among the Hungarian Romanies, notes the existence of an established tradition in the Kingdom of Hungary, where tribal chiefs, oftentimes styled as "Kings of Egypt/of the Gypsies", wore "the serpent engraved on the silver buttons on their coats".[7] MacRitchie speculates that the three adders on a shield at Nunraw armorial, in the Kingdom of Scotland, may therefore connect to John Faa and the Scottish Romanichal.[8] In the 1860s, John's nominal descendant, Esther Faa Blythe of Kirk Yetholm, used a tinsel coronet with the Scottish thistle.[9] Several 15th-century sources report the existence of heraldic symbols associated with nomadic "Gypsy Princes" from the Holy Roman Empire. One such figure, named Panuel, used a crowned golden eagle, while another one, Bautma, had a complex coat of arms, incorporating a scimitar and a crowned rooster; both figures also used hounds as their heraldic animal, with Panuel's being a badge.[10] A 1498 epitaph at Pforzheim commemorates a Freigraf of "Little Egypt", in fact a Romani tribal leader. His attached coat of arms has the star and crescent in combination with the stag.[11] In Wallachia and Moldavia, where they were kept as princely slaves, Romani craftsmen were directly involved in fabricating heraldic seals, albeit of a rudimentary kind.[12]

At the turn of the 18th century, the disunity and symbolic disorder of Romani tribes was a subject matter in Ion Budai-Deleanu's mock-epic, Țiganiada. A Romanian proto-nationalist of the Transylvanian School, Budai probably hinted at political disentanglement within his own ethnic community; Țiganiada shows Gypsies marking under numerous vexilloids: a shovel for the Boyash, a copper tray for the Kalderash, a stuffed crow for the Argintari, and a red sieve, painted on white rawhide leather, for the Ciurari.[13] In the 1830s, the English philanthropist James Crabb recalled meeting a Romani fortune-teller, whose saddle was "literally studded with silver; for she carried on it the emblems of her profession wrought in that metal; namely, a half-moon, seven stars, and the rising sun."[14] A group of Ursari captured in 1872 at Fribourg reportedly wore red bonnets.[15] By that stage, some Romani symbols had embraced more than tribal groups. These include a red banner carried by Turkish Romanies, all of whom belonged to a special esnaf (guild) of the Ottoman Empire.[16] Gypsies also served the Austrian Empire in Serbian Vojvodina during 1848, when they reportedly wore "colourful garbs" and carried their own banners.[17] A banner of the Kosovar Gypsies, dating from 1849, is still preserved in Prizren.[18]

British traditions tended to regard combinations of yellow and red, or yellow-red-black as "Gypsy". An English, non-Romani, cricket club called I Zingari ("The Gypsies") was established in 1845, with red, yellow (or gold), and black as its colors. "The oldest extant club colours in the UK", these had a contextual meaning, symbolizing the "coming out of darkness, through fire, and into light."[19] In 1890, one unnamed member of the Gypsy Lore Society (GLS) proposed that the European Gypsies were generally using red and yellow as their distinctive colors. He noted their recurrence in both the Romani folk dress and I Zingari kits, as well as the identification of "red and yellow for Romany" in one English rhyme. The same source rendered the words of a "Romany chal in Spain", according to whom there was a "tacit recognition" of red-yellow-black as a tribal tricolor; in that instance, the former two colors also replicated the Spanish red-weld.[20] The tricolor scheme had by then appeared on the cover of Borrow's Romany Vocabulary, printed in London for GLS use (1889).[21] MacRitchie placed doubt on this claim, noting that in earlier testimonies by Walter Simson the colors of Scottish Romani costumes are depicted as primarily green.[20] In a 1907 report for the GLS, James Yoxall briefly discussed "why yellow is so much a Gypsy colour". Yoxall hypothesized that a "distinctive hue" may have been forced "upon the wanderers of the roads" in medieval times, the same as yellow badges had been imposed on Jews.[22] Writing a year later, MacRitchie noted the "Gypsy colours of Spain" as used on Andrew McCormick's monograph of The Tinkler-Gypsies. He credited "the late Lord Lilford" as the ultimate source for the information published by the GLS in 1890.[23]

In Austria-Hungary, all Gypsies were informally attributed a "coat of arms" displaying the hedgehog. This was first used by Archduke Joseph Karl on his 1886 treatise, Czigány nyelvtan (where the animal is shown "with a twig in its mouth"),[24] and later etched into János Bihari's monument on Margaret Island.[25] The selection was validated by scholar Emil Ponori Thewrewk, who argued that the hedgehog was an "emblem shared by all the Gypsies", adding: "Gypsies from different countries distinguish themselves with hedgehogs that hold various cones or leaves (namely pine cones, birch or hawthorn leaves) in its mouth."[24] In 1888, Orientalist Wilhelm Solf described the "peculiar organisation of the Gypsies" in the German Empire. According to Solf, the tribal "captains" of the German Romanies each kept an "official seal, upon which a hedgehog is engraved—a beast held as sacred by all the Gypsies"; similarly, all groups favored the color green, symbolic of "honour".[20][26] There were three German Gypsy tribes, named for their respective area: Old Prussia, which carried a black-and-white flag defaced with a fir tree; New Prussia—green-and-white, with a birch tree; and Hanover—gold-blue-white with a mulberry tree.[20][26] GLS folklorist Friedrich Wilhelm Brepohl noted in 1911 that "Gypsy Princes" in Switzerland and elsewhere had coats of arms depicting "either a hedgehog, which is the gypsy's favorite animal, or a magpie—the sacred bird of the gypsies."[27] Guild organization was meanwhile maintained in the post-Ottoman Principality of Bulgaria—an association of Bulgarian Romani porters was set up in 1901; its flag is also preserved.[28] In 1910, Vidin became home to the first-ever civic organization for Romanies (still describing themselves as the "Egyptian Nation" or "Copts"). Its emblem showed Saint George slaying a crocodile, which, the group explained, was symbolic of Christianity vanquishing Egyptian paganism.[29]

- Early Romani heraldry

-

Detail of Francis Wheatley's etching, showing the drag harrow as a purported Gypsy symbol

-

David MacRitchie's reproduction of the "King of Egypt" arms in Nunraw

-

"Gypsy colours of Spain", as reported by Lord Lilford

-

Gypsy hedgehog emblem, as popularized by Archduke Joseph Karl

Romany Zoria, UGRR, and the Kwieks[edit]

The emergence Romani nationalism after World War I coincided roughly with the spread of communism and the proclamation of the Soviet Union. Groups which embraced both ideals also replicated communist symbolism. One early case was the Kingdom of Bulgaria, where left-wing Romanies established in 1920 an Egypt society, functioning as a branch of the Bulgarian Communist Party. This organization adopted a "wine-red flag".[30] In 1923, a small group of Russian Romanies appeared at the May Day parade in Red Square, holding up a banner inscribed with the message: "Gypsy Workers of the World, Unite!"[31] Romany Zoria appeared in late 1927 as a Soviet propaganda journal aimed at the Romani community, and aiming for their complete sedentarization as proletarians. It repeated the slogan, and published illustrations of the Romanies trampling on symbols of their nomadic lifestyle—primarily including the cartwheel.[32] In the early 1930s, Stalinist authorities envisaged colonizing Soviet Romanies and Assyrians "in compact groups to form [their own] national territories" along the border; a blueprint for this policy was set by the Jewish Autonomous Oblast.[33]

Greater Romania, as the home of a sizable Romani minority (including formerly Hungarian Romani communities in Transylvania), witnessed some of the first manifestations of Romani nationalism. In 1923, the Romanies of Teaca affirmed their collective existence as a "new minority" of "Transylvanian Gypsies", by adopting a flag. Its design is not specified beyond the colors, namely "black–yellow–red."[34] Among the early Romanian Romani organizers, Lazăr Naftanailă is known to have worn the Romanian national tricolor as a sash.[35]

According to historian Ian Hancock, the current flag originates with the world Romani flag proposed in late 1933 by Romania's General Union of the Romanies (UGRR), upon the initiative of Gheorghe A. Lăzăreanu-Lăzurică; the chakra was absent from that version, which was a plain bicolor. Scholar Ilona Klímová-Alexander argues that such a detail is "not confirmed by the statutes or any other source."[36] Other historians, including Elena Marushiakova, note the "lack of any real historical evidence" to substantiate Hancock's account, which they describe as a sample of "nation-building" mythology.[37] Sociologist Jean-Pierre Liégeois also describes the UGRR's Romani flag as a theorized concept, rather than an actual design,[38] whereas scholar Whitney Smith believes that the bicolor existed, but also that its designer remains unknown.[39] Lăzurică's own organization its own, better attested, flag, used to represent Romania's Romani community. It was described in the UGRR charter as a defaced Romanian tricolor, or "the Romanian national colors".[40] Its symbolism combined the national coat of arms with symbols of Romani tribes: "a violin, an anvil, a compass and a trowel crossed with a hammer."[41] The UGRR also used at least 36 regional flags, which were usually blessed in public ceremonies by representatives of the Romanian Orthodox Church, to which Lăzurică belonged.[42] One meeting held at Mediaș in May 1934 had vexilla, "similar to the flags of the old Roman legions", topped by tuning forks.[43]

In neighboring Poland, a Kalderash man, Matejasz Kwiek, established himself as a "King of the Gypsies". Though his clan was regarded by mainstream Polish Romanies as "Rumanian Gypsies",[44] he remained indifferent to Lăzurică's projects. A February 1935 report mentions various "Gypsy banners", as well as a sash and an "official seal", appearing at a ceremony in which Kwiek became "Leader of the Gypsy Nation".[45] One account suggests that King Matejasz's arms showed a Pharaoh's crown alongside three symbols of the Romanies' "wandering life": a hammer, anvil and whip.[46] The king's funeral in 1937 saw the flying of various blue and red banners, with slogans espousing Kwiek's loyalty toward Polish nationalism.[47] One report in the Journal des Débats describes the procession as carrying an ethnic flag "with the Kwiek dynastic emblem", alongside the flag of Poland.[48]

Following the ascension of Janusz Kwiek to the throne in Warsaw, journalists noted that the "Gypsy kingdom" was not yet flying a single flag of its own, and that "banners of various colors" were used.[49] A report in the Romanian newspaper Foaia Poporului described them more specifically as "hundreds of Gypsy flags, colored red, green, rose, and yellow."[50] Regional symbols also prevailed in Bulgaria: from 1930, its "Mohammedan" Romanies prioritized the star and crescent as symbols of Islam.[51] In the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Romanies united around the cult of Saint Sarah as Bibija used a blue banner displaying Sarah and Saint Nicholas together.[52] The Panhellenic Cultural Association of the Greek Gypsies, active under the Metaxas Regime, used a flag of unspecified color, adorned with the image of Saint Sophia.[53] In Britain, GLS affiliates such as Augustus John promoted the red-yellow-black arrangement as "Romany colours". These were used on the cover of the GLS Journal for the 1938 Jubilee issue.[21]

Janusz Kwiek began to look into territorial nationalism, drawing up a "government program" for a Romani state, and envisaging mass migration into Italian Ethiopia.[54] His project coincided with the agenda of Italian fascism, namely the deportation of peninsular Jews and "other persons who were considered racially dangerous, such as gypsies", to the new East African provinces.[55] By the mid 1930s, the initiative to use and recognize an international flag was taken up by the UGRR's new president, Gheorghe Nicolescu;[56] at the time, he corresponded with Kwiek's rival King, Mikita, who wished to establish a Romani state on the Ganges, or in Africa.[57] The "national Gypsy assembly", which he and Naftanailă convened in Sibiu in September 1934, had "about 72 flags" on display.[58] According to one report, the 1935 Romani congress in Bucharest, presided over by Nicolescu, had the "Romany flag" displayed alongside portraits of Adolf Hitler and Michael I of Romania.[59] Nicolescu soon proclaimed himself a Gypsy King—and, according to writer Mabel Farley Nandriș, who visited him in his Bucharest home, flew the "Gypsy standard with the Rumanian Arms on one side and the Gypsy Arms on the other—a pair of compasses to measure justice and a lute for music."[60] By 1937, his admiration for Nazism and the National Christian Party also resulted in UGRR usage of swastikas.[61]