User:Cynwolfe/Roman Empire notes

History[edit]

Principate (27 BC–AD 235)[edit]

Augustus (27 BC–AD 14)[edit]

Octavian, the grandnephew and heir of Julius Caesar, had made himself a central military figure during the chaotic period following Caesar's assassination. In 43 BC at the age of twenty he held his first consulship and became one of the three members of the Second Triumvirate, a political alliance with Lepidus, and Mark Antony.[1] In 36 BC, he was given the power of a Plebeian Tribune, which gave him veto power over the Senate and the ability to control the Plebeian Council, the principal legislative assembly. These powers made himself and his position sacrosanct. The triumvirate ended in 32 BC, torn apart by the competing ambitions of its members: Lepidus was forced into exile and Antony, who had allied himself with his lover Queen Cleopatra VII of Egypt, committed suicide in 30 BC following his defeat at the Battle of Actium (31 BC) by the fleet of Octavian commanded by his general Agrippa. Octavian subsequently annexed Egypt to the empire.[2]

Now sole ruler of Rome, Octavian began a full-scale reformation of military, fiscal and political matters. In 29 BC, he was given the authority of a Roman Censor and thus the power to appoint new senators.[3] The senate also granted him a unique grade of Proconsular imperium, giving him authority over all proconsuls, the military governors of the Empire.[4] The powers had he now secured for himself were in effect those that his predecessor Julius Caesar had secured for himself years earlier as Roman Dictator.

The provinces at the frontiers where the vast majority of legions were stationed, newly classified as imperial provinces, were now under the control of Octavian. The peaceful provinces were given to the authority of the Senate and were classified as senatorial provinces.[5] The legions, which had reached an unprecedented number of around fifty because of the civil wars, were concentrated and reduced to twenty-eight. Octavian also created nine special cohorts to maintain peace in Italy, keeping at least three stationed in Rome. The cohorts in the capital became known as the Praetorian Guard.

In 27 BC, Octavian offered to transfer control of the state back to the senate.[3] The Senate refused the offer, which in effect was a ratification of his position within the state. Octavian was also granted the title of "Augustus" by the Senate,[6] and took the title of Princeps or "first citizen".[4] As the adopted heir of Julius Caesar, Octavian, now referred to as "Augustus", took Caesar as a component of his name. By the time of the reign of Vespasian, the term Caesar had evolved from a family name into a formal title.

Augustus completed the conquest of Hispania, while subordinate generals expanded Roman possessions in Africa and Asia Minor. Augustus' final task was to ensure an orderly succession of his powers. His greatest general and stepson Tiberius had conquered Pannonia, Dalmatia, Raetia, and temporarily Germania for the Empire, and was thus a prime candidate. In 6 BC, Augustus granted tribunician powers to his stepson,[7] and soon after he recognized Tiberius as his heir. In 13 AD, a law was passed which extended Augustus' powers over the provinces to Tiberius,[8] so that Tiberius' legal powers were equivalent to, and independent from, those of Augustus.[8] In 14 AD Augustus died at the age of seventy-five, having ruled the empire for forty years.

Julio-Claudian dynasty[edit]

Augustus was succeeded by his stepson Tiberius, the son of his wife Livia from her first marriage. Augustus was a scion of the gens Julia (the Julian family), one of the most ancient patrician clans of Rome, while Tiberius was a scion of the Claudia. Their three immediate successors were all descended from the gens Claudia, through Tiberius's brother Nero Claudius Drusus. They also descended from the gens Julia, emperors Caligula and Nero through Julia the Elder, Augustus's daughter from his first marriage, and emperor Claudius through Augustus's sister Octavia Minor. Historians refer to their dynasty as the "Julio-Claudian Dynasty".[9]

The early years of Tiberius's reign were relatively peaceful. However, his rule soon became characterized by paranoia. He began a series of treason trials and executions, which continued until his death in 37.[10] The logical successor to the much hated Tiberius was his 24-year-old grandnephew Caligula. Caligula's reign began well, but after an illness he became tyrannical and insane. In 41 Caligula was assassinated, and for two days following his assassination, the senate debated the merits of restoring the Republic.[11]

Due to the demands of the army, however, Claudius was ultimately declared emperor. Claudius was neither paranoid like his uncle Tiberius, nor insane like his nephew Caligula, and was therefore able to administer the Empire with reasonable ability. Claudius ordered the suspension of further attacks across the Rhine,[12] setting what was to become the permanent limit of the Empire's expansion in this direction.[13] In his own family life he was less successful, as he married his niece, who may very well have poisoned him in 54.[14]

Nero, who succeeded Claudius, focused much of his attention on diplomacy, trade, and increasing the cultural capital of the Empire. Nero, though, is remembered as a tyrant, and was forced to commit suicide in 68.

Military emperors[edit]

Nero was followed by a brief period of civil war, known as the "Year of the Four Emperors". Augustus had established a standing army, where individual soldiers served under the same military governors over an extended period of time. The consequence was that the soldiers in the provinces developed a degree of loyalty to their commanders, which they did not have for the emperor. Thus the Empire was, in a sense, a union of inchoate principalities, which could have disintegrated at any time.[15] Between June 68 and December 69, Rome witnessed the successive rise and fall of Galba, Otho and Vitellius until the final accession of Vespasian, first ruler of the Flavian dynasty. These events showed that any successful general could legitimately claim a right to the throne.[16]

In AD 69, Marcus Salvius Otho had the Emperor Galba murdered[17][18] and claimed the throne for himself,[19][20] but Vitellius had also claimed the throne.[21][22] Otho left Rome, and met Vitellius at the First Battle of Bedriacum,[23] after which the Othonian troops fled back to their camp,[24] and the next day surrendered to the Vitellian forces.[25] Meanwhile, the forces stationed in the Middle East provinces of Judaea and Syria had acclaimed Vespasian as emperor.[23] Vespasians' and Vitellius' armies met in the Second Battle of Bedriacum,[23][26] after which the Vitellian troops were driven back into their camp.[27] Vespasian, having successfully ended the civil war, was declared emperor.

Vespasian, though a successful emperor, continued the weakening of the Senate which had been going on since the reign of Tiberius. Through his sound fiscal policy, he was able to build up a surplus in the treasury, and began construction on the Colosseum. Titus, Vespasian's successor, quickly proved his merit, although his short reign was marked by disaster, including the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in Pompeii. He held the opening ceremonies in the still unfinished Colosseum, but died in 81. His brother Domitian succeeded him. Having exceedingly poor relations with the Senate, Domitian was murdered in September 96.

Nerva-Antonine dynasty[edit]

The next century came to be known as the period of the "Five Good Emperors", in which the successions were peaceful and the Empire was prosperous. Each emperor of this period was adopted by his predecessor. The last two of the "Five Good Emperors" and Commodus are also called Antonines.[28] After his accession, Nerva, who succeeded Domitian, set a new tone: he restored much confiscated property and involved the Senate in his rule.

Starting in the year 101, Trajan undertook two military campaigns against gold-rich Dacia, which he finally conquered in 106 (see Trajan's Dacian Wars).[29][30][31] Following an uncertain number of battles, Trajan marched into Dacia,[32] besieged the Dacian capital and razed it to the ground.[33] With Dacia quelled, Trajan subsequently invaded the Parthian empire to the east. In 112, Trajan marched on Armenia and annexed it to the Roman Empire. Then he turned south into Parthia, taking several cities before declaring Mesopotamia a new province of the Empire, and lamenting that he was too old to follow in the steps of Alexander the Great. During his rule, the Roman Empire expanded to its largest extent, and would never again advance so far to the east.[34]

Hadrian's reign was marked by a general lack of major military conflicts, but he had to defend the vast territories that Trajan had acquired.

Antoninus Pius's reign was comparatively peaceful.[35] During the reign of Marcus Aurelius, Germanic tribes launched many raids along the northern border. The period of the "Five Good Emperors", also commonly described as the Pax Romana ("Roman Peace") was brought to an end by the reign of Commodus. Commodus was the son of Marcus Aurelius, breaking the scheme of adoptive successors that had turned out so well. Commodus became paranoid and slipped into insanity before being murdered in 192.[36]

Severan dynasty[edit]

The Severan Dynasty, which lasted from 193 until 235, included several increasingly troubled reigns.[37] A generally successful ruler, Septimius Severus, the first of the dynasty, cultivated the army's support and substituted equestrian officers for senators in key administrative positions.[38] In 197, he waged a brief and successful war against the Parthian Empire, during which time the Parthian capital was sacked, and the northern half of Mesopotamia was restored to Rome.

Severus' successor Caracalla passed uninterrupted for a while. Most notably, he extended full Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants of the Empire. In 217, Caracalla marched on Parthia from Edessa.[39] Increasingly unstable and autocratic, Caracalla was assassinated while on the march by Macrinus,[40][41] who proclaimed himself emperor in his place. The troops of Elagabalus declared him to be emperor instead, and the two met in battle at the Battle of Antioch in AD 218, in which Macrinus was defeated.[42] Elagabalus was murdered shortly afterwards;[42]

After overthrowing the Parthian confederacy,[43][44] the Sassanid Empire that arose from its remains pursued a more aggressive expansionist policy than their predecessors[45][46] and continued to make war against Rome. In 230, the first Sassanid emperor attacked Roman territory,[46]

Alexander Severus, the last of the dynasty, was proclaimed emperor, but was unable to control the army and was assassinated in 235.[47][42] His murderers raised in his place Maximinus Thrax, who was in turn murdered[48] when it appeared to his forces as though he would not be able to best the senatorial candidate for the throne, Gordian III.

Crisis of the Third Century[edit]

in 243, Gordian's army defeated the Sassanids at the Battle of Resaena.[49] His own fate is not certain, although he may have been murdered by his successor, Philip the Arab, who ruled for only a few years before the army proclaimed another general as emperor, this time Decius, who defeated Philip and seized the throne.[50] Gallienus, emperor from AD 260 to 268, saw a remarkable array of usurpers.

A military that was often willing to support its commander over its emperor meant that commanders could establish sole control of the army they were responsible for and usurp the imperial throne. The so-called Crisis of the Third Century describes the turmoil of murder, usurpation and in-fighting that is traditionally seen as developing after the murder of Alexander Severus in 235.[51] During the near-collapse of the Roman Empire between 235 and 284, 25 emperors reigned, and the empire experienced extreme military, political, and economic crises. Additionally, in 251, the Plague of Cyprian broke out, causing large-scale mortality which may have seriously affected the ability of the Empire to defend itself.[52] In 253 the Sassanids under Shapur I penetrated deeply into Roman territory, defeating a Roman force at the Battle of Barbalissos[53] and conquering and plundering Antioch.[43][53] In 260 at the Battle of Edessa the Sassanids defeated the Roman army[54] and captured the emperor Valerian.[43][46]

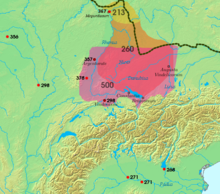

The essential problem of large tribal groups on the frontier remained much the same as the situation Rome faced in earlier centuries; the 3rd century saw a marked increase in the overall threat. Some mix of Germanic peoples, Celts, and tribes of mixed Celto-Germanic ethnicity were settled in the lands of Germania from the 1st century onwards.[55][56] The assembled warbands of the Alamanni frequently crossed the border, attacking Germania Superior such that they were almost continually engaged in conflicts with the Roman Empire. However, their first major assault deep into Roman territory did not come until 268. In that year the Romans were forced to denude much of their German frontier of troops in response to a massive invasion by another new Germanic tribal confederacy, the Goths, from the east. The pressure of tribal groups pushing into the Empire was the end result of a chain of migrations with its roots far to the east.[57] The Alamanni seized the opportunity to launch a major invasion of Gaul and northern Italy. However, the Visigoths were defeated in battle that summer and then routed in the Battle of Naissus.[58] The Goths remained a major threat to the Empire but directed their attacks away from Italy itself for several years after their defeat.

The Alamanni on the other hand resumed their drive towards Italy almost immediately. They defeated Aurelian at the Battle of Placentia in 271 but were beaten back for a short time, only to reemerge fifty years later. The core problems would remain and cause the eventual destruction of the western empire.

Tetrarchy[edit]

The accession of Diocletian, who reigned from 284 until 305, marks the end of the period conventionally known as the Crisis of the Third Century. Diocletian was able to address many of the acute problems experienced during this crisis, including a treaty in 297 with Narseh that produced a peace between Rome and the Sassanid Empire that lasted until 337.

Diocletian, a usurper himself, defeated Carinus to become emperor. Diocletian saw the vast empire as ungovernable, and therefore split the Roman Empire in half and created two equal emperors to rule under the title of Augustus. In doing so, he effectively created what would become the Western Roman Empire and the Eastern Roman Empire. In 293 authority was further divided, as each Augustus took a junior Emperor called a Caesar to provide a line of succession. This constituted what is now known as the Tetrarchy ("rule of four"). Some small measure of stability again returned, with the empire split into a tetrarchy of two greater and two lesser emperors, a system that staved off civil wars for a short time until AD 312. The transitions of this period mark the beginnings of Late Antiquity.[59]

Constantinian dynasty[edit]

The Tetrarchy effectively collapsed with the death of Constantius Chlorus, the first of the Constantinian dynasty, in 306. Constantius's troops immediately proclaimed his son Constantine the Great as Augustus. A series of civil wars broke out, which ended with the entire empire being united under Constantine. In 312, relations between the tetrarchy collapsed for good. Constantine legalised Christianity definitively in 313 through the Edict of Milan.[60]From AD 314 onwards, he defeated Licinius in a series of battles. Constantine then turned to Maxentius, beating him in the Battle of Verona and the Battle of Milvian Bridge.

Just before the death of Constantine I in 337, Shapur II broke the peace and renewed what would become a twenty-six-year conflict with the Sassanid Empire, attempting with little success to conquer Roman fortresses in the region.

In 361, after further episodes of civil war, Julian became emperor. His edict of toleration in 362 ordered the reopening of pagan temples, and, more problematically for the Christian Church, the recalling of previously exiled Christian bishops. Julian eventually resumed the war against Shapur II of Persia, although he received a mortal wound at the Battle of Ctesiphon and died in 363. The Romans were victorious but were unable to take the city and were forced to retreat. There were several later wars.[61] Julian's officers then elected Jovian as emperor. Jovian ceded territories won from the Persians as far back as Trajan's time, and restored the privileges of Christianity, before dying in 364.

Valentinian dynasty[edit]

Upon Jovian's death, Valentinian I, the first of the Valentinian dynasty, was elected Augustus, and chose his brother Valens to serve as his co-emperor.[62] In 365, Procopius managed to bribe two legions, who then proclaimed him Augustus. War between the two rival Eastern Roman Emperors continued until Procopius was defeated, although in 367, eight-year-old Gratian was proclaimed emperor by the other two. In 375 Valentinian I led his army in a campaign against a Germanic tribe, but died shortly thereafter. Succession did not go as planned. Gratian was then a 16-year-old and arguably ready to act as Emperor, but the troops proclaimed his infant half-brother emperor under the title Valentinian II, and Gratian acquiesced.[63]

Meanwhile, the Eastern Roman Empire faced its own problems with Germanic tribes. One tribe fled their former lands and sought refuge in the Eastern Roman Empire. Valens let them settle on the southern bank of the Danube in 376, but they soon revolted against their Roman hosts. Valens personally led a campaign against them in 378.[64] However this campaign proved disastrous for the Romans. The two armies approached each other near Adrianople, but Valens was apparently overconfident of the numerical superiority of his own forces over the enemy. Valens, eager to have all of the glory for himself, rushed into battle, and on 9 August 378, the Goths inflicted a crushing defeat on the Romans at the Battle of Adrianople, resulting also in the death of Valens.[64] In 378 on the Eastern Empire at the Battle of Adrianople.[65][66] Contemporary historian Ammianus Marcellinus estimated that two-thirds of the Roman soldiers on the field were lost. The battle had far-reaching consequences, as veteran soldiers and valuable administrators were among the heavy casualties, which left the Empire with the problem of finding suitable leadership. Gratian was now effectively responsible for the whole of the Empire. He sought however a replacement Augustus for the Eastern Roman Empire, and in 379 chose Theodosius I.[64]

Theodosian dynasty[edit]

Theodosius, the founder of the Theodosian dynasty, proclaimed his five-year-old son Arcadius an Augustus in 383 in an attempt to secure succession. Hispanic Celt general Magnus Maximus, stationed in Roman Britain, was proclaimed Augustus by his troops in 383 and rebelled against Gratian when he invaded Gaul. Gratian fled, but was assassinated. Following Gratian's death, Maximus had to deal with Valentinian II, at the time only twelve years old, as the senior Augustus. Maximus soon entered negotiations with Valentinian II and Theodosius, attempting and ultimately failing to gain their official recognition. Theodosius campaigned west in 388 and was victorious against Maximus, who was captured and executed. In 392 Valentinian II was murdered, and shortly thereafter Arbogast arranged for the appointment of Eugenius as emperor.[67]

The eastern emperor Theodosius I refused to recognise Eugenius as emperor and invaded the West again, defeating and killing Arbogast and Eugenius. He thus reunited the entire Roman Empire under his rule. Theodosius was the last Emperor who ruled over the whole Empire. As emperor, he made Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire.[68] After his death in 395, he gave the two halves of the Empire to his two sons Arcadius and Honorius. The Roman state would continue to have two different emperors with different seats of power throughout the 5th century, though the Eastern Romans considered themselves Roman in full. The two halves were nominally, culturally and historically, if not politically, the same state.

References[edit]

- ^ Eck, Werner; translated by Deborah Lucas Schneider; new material by Sarolta A. Takács. (2003) The Age of Augustus. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. p12

- ^ Paul K. Davis, 100 Decisive Battles from Ancient Times to the Present: The World’s Major Battles and How They Shaped History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 63.

- ^ a b Abbott, 267

- ^ a b Abbott, 269

- ^ Eck, Werner; translated by Deborah Lucas Schneider; new material by Sarolta A. Takács. (2003) The Age of Augustus. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. p40

- ^ Abbott, 268

- ^ Abbott, 272

- ^ a b Abbott, 273

- ^ Brill's New Pauly, "Julio-Claudian emperors"

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural Histories XXVIII.5.23.

- ^ Abbott, 293

- ^ Goldsworthy, In the Name of Rome, p. 269

- ^ Luttwak, The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire, p. 38

- ^ Scramuzza, Vincent (1940). The Emperor Claudius Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p29

- ^ Abbott, 296

- ^ Abbott, 298

- ^ Tacitus, The Histories, Book 1, ch. 41

- ^ Plutarch, Lives, Galba

- ^ Luttwak, The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire, p. 51

- ^ Lane Fox, The Classical World, p. 542

- ^ Tacitus, The Histories, Book 1, ch. 57

- ^ Plutarch, Lives, Otho

- ^ a b c Luttwak, The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire, p. 52

- ^ Tacitus, The Histories, Book 1, ch. 44

- ^ Tacitus, The Histories, Book 1, ch. 49

- ^ Tactitus, The Histories, Book 3, ch. 18

- ^ Tactitus, The Histories, Book 3, ch. 25

- ^ McKay, John P.; Hill, Bennett D.; Buckler, John; Ebrey, Patricia B.; & Beck, Roger B. (2007)

- ^ Goldsworthy, In the Name of Rome, p. 322

- ^ Matyszak, The Enemies of Rome, p. 213

- ^ Matyszak, The Enemies of Rome, p. 215

- ^ Matyszak, The Enemies of Rome, p. 222

- ^ Matyszak, The Enemies of Rome, p. 223

- ^ Nelson, Eric (2002). Idiots guide to the Roman Empire.. Alpha Books. pp. 207–209. ISBN 0-02-864151-5.

- ^ Bury, J. B. A History of the Roman Empire from its Foundation to the Death of Marcus Aurelius. p525

- ^ Dio Cassius 72.36.4.

- ^ Simon Swain, Stephen Harrison and Jas Elsner (eds), Severan culture (Cambridge, CUP, 2007).

- ^ Birley, Anthony R. (1999) [1971]. Septimius Severus: The African Emperor. London: Routledge. p113.

- ^ Grant, The History of Rome, p. 279

- ^ "Caracalla" The New Zealand Oxford Dictionary. Tony Deverson. Oxford University Press 2004. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, p. 129

- ^ a b c Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, p. 130

- ^ a b c Grant, The History of Rome, p. 283

- ^ Luttwak, The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire, p. 128

- ^ Matyszak, The Enemies of Rome, p. 234

- ^ a b c Luttwak, The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire, p. 151

- ^ Dio, 60:20:2

- ^ Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, p. 131

- ^ Matyszak, The Enemies of Rome, p. 235

- ^ Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, p. 135

- ^ Grant, The History of Rome, p. 280

- ^ Christine A. Smith. Plague in the Ancient World: A Study from Thucydides to Justinian.Loyola University New Orleans.

- ^ a b Matyszak, The Enemies of Rome, p. 236

- ^ Matyszak, The Enemies of Rome, p. 237

- ^ Luttwak, The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire, p. 146

- ^ Grant, The History of Rome, p. 282

- ^ Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, p. 624

- ^ Grant, The History of Rome, p. 285

- ^ Glen W. Bowersock, "The Vanishing Paradigm of the Fall of Rome" Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 49.8 (May 1996:29-43) p 34

- ^ Potter, David Stone, The Roman Empire at Bay, AD 180-395, Routledge, 2004. p334.

- ^ Gibbon. "Decline and Fall" chapter 23

- ^ Kulikowski, M. Rome's Gothic Wars: from the third century to Alaric. 2007. pg 162

- ^ Theodosian Code 16.10.20; Symmachus Relationes 1–3; Ambrose Epistles 17–18.

- ^ a b c Ammianus Marcellinus, Historiae, book 31, chapters 12–14.

- ^ Ammianus Marcellinus, Historiae, book 31.

- ^ Jordanes, The Origins and Deeds of the Goths, 138.

- ^ Williams, Stephen and Gerard Friell, Theodosius: The Empire at Bay, Yale University Press, 1994. p134.

- ^ Edict of Thessolonica": See Codex Theodosianus XVI.1.2