User:DipDopDip/Remix Culture

READY FOR GRADING

| This is the sandbox page where you will draft your initial Wikipedia contribution.

If you're starting a new article, you can develop it here until it's ready to go live. If you're working on improvements to an existing article, copy only one section at a time of the article to this sandbox to work on, and be sure to use an edit summary linking to the article you copied from. Do not copy over the entire article. You can find additional instructions here. Remember to save your work regularly using the "Publish page" button. (It just means 'save'; it will still be in the sandbox.) You can add bold formatting to your additions to differentiate them from existing content. |

Article Draft[edit]

Remix culture, sometimes read-write culture, is a term describing a society that allows and encourages derivative works by combining or editing existing materials to produce a new creative work or product.[2][3] Remix cultures are permissive of efforts to improve upon, change, integrate, or otherwise remix the work of creators and copyright holders, with or without their permission. While combining elements has always been a common practice of artists of all domains throughout human history,[4] the growth of exclusive copyright restrictions in the last several decades limits this practice more and more by the legal chilling effect.[5] In reaction, Harvard law professor Lawrence Lessig, who considers remixing a desirable concept for human creativity, has worked since the early 2000s[6] on a transfer of the remixing concept into the digital age. Lessig founded the Creative Commons in 2001, which released Licenses as tools to enable remix culture again, as remixing is legally prevented by the default exclusive copyright regime applied currently on intellectual property. The remix culture for cultural works is related to and inspired by the earlier Free and open-source software for software movement, which encourages the reuse and remixing of software works.

Description[edit]

Lawrence Lessig described the Remix culture in his 2008 book Remix. Lawrence compared the default media culture of the 20th century to the usage of computer technology terminology as Read/Write culture (RW) vs. Read Only culture (RO).[9]

In the usual Read Only media culture, the culture is consumed more or less passively.[9] The information or product is provided by a 'professional' source, the content industry, that possesses an authority on that particular product/information. There is a one-way flow only of creative content and ideas due to a clear role separation between content producer and content consumer. The emergence of Analog mass production and duplication technologies (pre-Digital revolution and internet like radio broad-casting) enabled the RO culture's business model of production and distribution and limited the role of the consumer to consumption of media.

Digital technology does not have the 'natural' constraints of the analog that preceded it. RO culture had to be recoded in order to compete with the "free" distribution made possible by the Internet. This is primarily done in the form of Digital Rights Management (DRM), which imposes restrictions on usage. Regardless, DRM has proven largely ineffective in enforcing constraints on digital media.[10][11]

Read/Write culture has a reciprocal relationship between the producer and the consumer. Taking works, such as songs, and appropriating them in private circles is exemplary of RW culture, which was considered to be the 'popular' culture before the advent of reproduction technologies.[9] The technologies and copyright laws that soon followed, however, changed the dynamics of popular culture. As it became professionalized, people were taught to defer production to the professionals.

Digital technologies provide the tools for reviving RW culture and democratizing production, sometimes referred to as Web 2.0. Blogs explain the three layers of this democratization. Blogs have redefined our relationship to the content industry as they allowed access to non-professional, user-generated content. The 'comments' feature that soon followed provided a space for readers to have a dialogue with the amateur contributors. 'Tagging' of the blogs by users based on the content provided the necessary layer for users to filter the sea of content according to their interest. The third layer added bots that analyzed the relationship between various websites by counting the clicks between them and, thus, organizing a database of preferences. The three layers working together established an ecosystem of reputation that served to guide users through the blogosphere. While there is no doubt many amateur online publications cannot compete with the validity of professional sources, the democratization of digital RW culture and the ecosystem of reputation provides a space for many talented voices to be heard that was not available in the pre-digital RO

History[edit]

Analog era[edit]

Remixing as digital age phenomena[edit]

Internet and Web 2.0[edit]

Foundation of the Creative Commons[edit]

Copyright[edit]

Domains of remixing[edit]

Folklore and vocal traditions[edit]

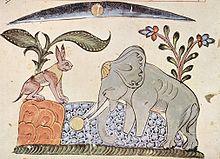

Graphic arts[edit]

Books and other information[edit]

Software and other digital goods[edit]

Music[edit]

- DJing is the act of live rearranging and remixing of pre-recorded music material to new compositions. From this music, the term remix spread to other domains.

- Sampling in music making is an example of reuse and remix to produce a new work. Sampling is widely popular within hip-hop culture. Grandmaster Flash and Afrika Bambaataa were some of the earliest hip-hop artists to employ the practice of sampling. This practice can also be traced to artists such as Led Zeppelin, who interpolated substantial portions of music by many acts including Willie Dixon, Howlin' Wolf, Jake Holmes, and Spirit. By taking a small clip of an existing song, changing different parameters such as pitch, and incorporating it into a new piece, the artist can make it their own.

- Music mashups are blends of existing music tracks. The 2004 album dj BC presents The Beastles received acclaim and was featured in Newsweek and Rolling Stone. A second album named Let It Beast with cover art by cartoonist Josh Neufeld was produced in 2006. Mashup DJ Gregg Gillis, who performs as Girl Talk, crafts entire albums out of remixed material, and cites Fair Use privileges to sample copyrighted works.[14] Other notable mashup DJs include Danger Mouse, Dean Gray, and DJ Earworm.

- Some genres of music are defined by their usage of remixing. DJ Screw created the Chopped and Screwed genre by accidentally playing a record that was meant for 45 rpm at 33 1⁄3 rpm, creating a slowed, laid-back, psychedelic effect.[15] Over the slowed down track Screw would layer drum tracks and then scratch the records to create a classic Southern hip-hop sound.[15] Nightcore is a genre that speeds up mainstream rock, pop, and EDM songs, often with additional production.[16] The sped -up nature leads to the original song playing at a higher pitch, so the production added usually fills out the low-end with heavy bass and then adds other high pitched elements to enhance the energy of the song.[16] Building upon Plunderphonics and Chopped and Screwed, Vaporwave as a musical genre involves slowing down smooth jazz, RnB, and Elevator music and usually adding reverb and backing synths, creating a trippy new-age ambience.[17]

Film and video[edit]

GIFs[edit]

Fan fiction[edit]

Fanfiction is an example of remix culture in action, in relation to various forms of fictional and non-fictional media, including books, TV shows, movies, musicians, actors, and more. Fan fiction is a written, remixed fiction which draws on the characters of the writers fandom, in order to tell the fan fiction writers own story, or their version of the original story.[18] Remix Culture relies on creators taking one work and repurposing it for another use[19] just as fanfiction takes an existing work and repurposes it for a new story, or series of events. Steven Hetcher writes that fanfiction, and remix culture at a broader level, can provide social benefit to the societies who participate in writing and reading fanfiction by providing a creative outlet.[20] Fanfiction remixes sometimes change aspects of the characters or setting, often called an alternative universe, with some writers putting pre-existing characters in a new setting, and others taking an established setting and placing in new characters.[21] In the social norms of fan fiction, it is rare for writers to publish or profit off of their works, and so copyright owners and authors rarely enforce copyright law, as these works help form communities and promote the original work.[21]

TikTok[edit]

The app TikTok has become a relevant media platform that utilizes remix culture as a marketing and engagement technique, using it to market products to viewers while also entertaining them.[22] Content creators and brands can now collaborate in an environment where remixing content is accepted and encouraged to gain followers through creative videos following trending actions, audios, and memes.[23] Older songs and celebrities are making comebacks by being attached to remix trends, their music or content is now being viewed again by being attached to a trend. Garnering attention for the artist and these bits is a marketing technique that makes viewers want to investigate the artist more.[24] Musicians like Doja Cat and Lil Nas X are two current musicians that have culminated their music in the TikTok remix culture. For example, "Remember (Walking In The Sand)" the 1960s song by the Shangri-Las has recently been remixed to an EDM track that brought more attention to the song and a following into it due to a popular TikTok trend circulating largely in 2020.[25] These trending songs allow for music on TikTok to become spreadable and testable. Companies and artists can test out music bits and loops to see how successful they may become before fully releasing them.

Intertwining of media cultures[edit]

Effects on artists[edit]

Artists participating in remix culture can potentially suffer consequences for violating copywrite or intellectual property law. English rock band The Verve were sued over their 1997 song "Bittersweet Symphony" sampling an arrangement of The Rolling Stones' "The Last Time."[26] The Verve were court-ordered to pay 100% of the song's royalties to The Rolling Stones' publishers and to give writing credit to Jagger and Richards.[26] This was resolved in 2019 as Richard Ashcroft of The Verve announced that Jagger and Richards signed over the publishing rights to the song, admitting it was their manager's decision to claim the songs' royalties[27].

Remix culture has created an environment that is nearly impossible for artists to create or own "original work". Media and the internet have made art so public that it leaves the work up for other interpretation and, in return, remixing. A major example of this in the 21st century is the idea of memes. Once a meme is put into cyberspace it is automatically assumed that someone else can come along and remix the picture. For example, the 1964 self-portrait created by artist René Magritte, "Le Fils De L'Homme", was remixed and recreated by street artist Ron English in his piece "Stereo Magritte". (Removed note that said that there is more about memes later in the article)

(removed unnecessary word)Despite the legal complexities of copywrite protections, remixed works continue to be popular in the mainstream. Rapper Lil Nas X's "Old Town Road," released in 2018, includes a sample by the industrial metal band Nine Inch Nails, while also blending the genres of hip-hop and country music. "Old Town Road" was a smash hit, setting a record of 19 weeks at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 Chart.[28] Four official remixes of "Old Town Road" were released, the first of which featured country singer Billy Ray Cyrus. This formula for genre-hybridization inspired countless unofficial remixes of the track, appropriated for various uses.[28]

Copyright and remixing for disability services[edit]

Reception and impact[edit]

In February 2010, Cato Institute's Julian Sanchez praised the remix activities for its social value, "for performing social realities" and remarked that copyright should be evaluated regarding the "level of control permitted to be exercised over our social realities".[29][30] Memes have also become a form of political protest and dissent as well as tools used by everyday people as a form of a subversion of the power narrative.[31] Author Apryl Williams asserts the meme and its effect on the Black Lives Matter movement as an example of the influence of this digital medium on raising awareness of issues as well as its ability to shift a narrative.[32]

According to Kirby Ferguson in his popular video series and TED talk,[34] everything is a remix, and that all original material builds off of and remixes previously existing material.[35] He argues if all intellectual property is influenced by other pieces of work, copyright laws would be unnecessary. Ferguson described that, the three key elements of creativity — copy, transform, and combine — are the building blocks of all original ideas; building on Pablo Picasso's famous quote "Good artists copy, great artists steal.".[33]

Criticism[edit]

But the culture is not without its critics even going so far in accusations of plagiarism.[36][37] In his 2006 book Cult of the Amateur,[38] Web 2.0 critic Andrew Keen criticizes the culture.[39] In 2011 UC Davis professor Thomas W. Joo criticized remix culture for romanticizing free culture[40] while Terry Hart had a similar line of criticism in 2012.[41]

See also[edit]

- Commons-based peer production

- Culture jamming

- Fandom

- Good Copy Bad Copy

- Prosumer

- Recombinant culture

Article body[edit]

- ^ downloads on creativecommons.org "The building blocks icon used to represent “to remix” is derived from the FreeCulture.org logo."

- ^ Remixing Culture And Why The Art Of The Mash-Up Matters on Crunch Network by Ben Murray (Mar 22, 2015)

- ^ Ferguson, Kirby. "Everything Is A Remix". Retrieved 2011-05-01.

- ^ Rostama, Guilda (June 1, 2015). "Remix Culture and Amateur Creativity: A Copyright Dilemma". WIPO. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

Most cultures around the world have evolved through the mixing and merging of different cultural expressions.

- ^ Larry Lessig (2007-03-01). "Larry Lessig says the law is strangling creativity". TEDx. ted.com. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- ^ School, Harvard Law. "Lawrence Lessig | Harvard Law School". hls.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2018-11-25.

- ^ Download Lessig’s Remix, Then Remix It on wired.com (May 2009)

- ^ Remix on lessig.org

- ^ a b c Larry Lessig (2007-03-01). "Larry Lessig says the law is strangling creativity". TEDx. ted.com. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- ^ A New Deal for Copyright on Locus Magazine by Cory Doctorow (2015)

- ^ The Role of Scientific and Technical Data and Information in the Public Domain: Proceedings of a Symposium. on National Academies Press (US); 15. The Challenge of Digital Rights Management Technologies by Julie Cohen (2003)

- ^ Jacobs 1888, Introduction, page xv; Ryder 1925, Translator's introduction, quoting Hertel: "the original work was composed in Kashmir, about 200 B.C. At this date, however, many of the individual stories were already ancient."

- ^ Doris Lessing, Problems, Myths and Stories, London: Institute for Cultural Research Monograph Series No. 36, 1999, p 13

- ^ Jensen, Christopher (October 4, 2007). "Doctor of the Monster Mash: Gregg Gillis of Girl Talk packs dance floors and challenges conventions with his onslaught of Top 40 samples". Minneapolis Star Tribune. p. 18.

- ^ a b Vargas, Samantha G. (2021-05). Chopped and Screwed: The Impact of DJ Screw(Thesis). Texas State University

- ^ a b Winston, Emma (2017-02-24). "Nightcore and the Virtues of Virtuality". Brief Encounters. 1 (1). doi:10.24134/be.v1i1.20. ISSN 2514-0612.

- ^ Glitsos, Laura (2018-01). "Vaporwave, or music optimised for abandoned malls". Popular Music. 37 (1): 100–118. doi:10.1017/S0261143017000599. ISSN 0261-1430.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Bailey, Jane; Steeves, Valerie M (2015). eGirls, eCitizens: putting technology, theory and policy into dialogue with girls' and young women's voices. ISBN 978-0-7766-2622-2. OCLC 1158219074.

- ^ Curran, James; Fenton, Natalie; Freedman, Des (2016-02-05). Misunderstanding the Internet. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-69562-4.

- ^ Kahan, Marcel (2001). "The Limited Significance of Norms for Corporate Governance". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 149 (6): 1869–1900. doi:10.2307/3312900. ISSN 0041-9907. JSTOR 3312900.

- ^ a b Hetcher, Steven A. (2009). "Using Social Norms to Regulate Fan Fiction and Remix Culture". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 157 (6): 1869–1935. ISSN 0041-9907.

- ^ Jeremy Yang; Juanjuan Zhang; Yuhan Zhang. "Research Brief : INFLUENCER VIDEO ADVERTISING IN TIKTOK" (PDF). Ide.mit.edu. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ "Why TikTok's co-creation culture helps brands engage with the community | IMA | Influencer Marketing Agency | Open Mic | the Drum". Archived from the original on 2021-10-20. Retrieved 2021-10-28.

- ^ Cohen, James; Kenny, Thomas (2 April 2020). Producing New and Digital Media: Your Guide to Savvy Use of the Web. ISBN 9780429574900.

- ^ Heffler, Jason. "That "Oh No" Song From TikTok Was Remixed Into an EDM Track—And It Actually Works". Edm.com. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ a b McDonald II, C. Austin (2013). "The Hero of Copyright Reform: Exploring Non-Cochlear Impacts of Girl Talk's Plunderphonics". Kaleidoscope: A Graduate Journal of Qualitative Communication Research. 12: 8 – via Google Scholar.

- ^ Savage, Mark (2019-05-23). "The Bitter Sweet Symphony dispute is over". BBC News. Retrieved 2022-09-29.

- ^ a b Stanfill, Mel (2021). "Can't nobody tell me nothin': 'Old Town Road', resisting musical norms, and queer remix reproduction". Popular Music. 40 (3–4): 347–363. doi:10.1017/S026114302100057X. ISSN 0261-1430.

- ^ Julian Sanchez (2010-04-01). "Lawrence Lessig: Re-examining the remix" (video). TEDxNYED. ted.com. Retrieved 2016-02-27.

Time 7:14: "social remixes [...] for performing social realities"; 8:00 "copyright policies about [...] level of control permitted to be exercised over our social realities"

- ^ The Evolution of Remix Culture by Julian Sanchez (2010-02-05)

- ^ Vickery, Jacqueline Ryan (2017-10-31). "Mapping The Affordances And Dynamics Of Activist Hashtags". AoIR Selected Papers of Internet Research. ISSN 2162-3317.

- ^ Williams, Apryl (October–December 2020). "Black Memes Matter: #LivingWhileBlack With Becky and Karen". Social Media + Society. 6 (4): 14. doi:10.1177/2056305120981047. S2CID 230282334.

- ^ a b The Three Key Steps to Creativity: Copy, Transform, and Combine by Eric Ravenscraft on lifehacker.com (2014-10-04)

- ^ a b Picard, Melanie (August 6, 2013). "Thoughts on Remix Culture, Copyright, and Creativity". Story 2023. Archived from the original on February 5, 2016. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- ^ Ferguson, Kirby. "Everything's A Remix". Everything Is A Remix Part 1. Retrieved 2011-05-02.

- ^ Reynolds, Simon (October 6, 2012). "Why Doesn't Anyone Believe in Genius Anymore?". Slate Magazine.

- ^ LaFrance, Adrienne (May 3, 2017). "When a 'Remix' Is Plain Ole Plagiarism". The Atlantic.

- ^ Keen, Andrew (May 16, 2006). Web 2.0; The second generation of the Internet has arrived. It's worse than you think. Archived 2006-02-24 at the Wayback Machine The Weekly Standard

- ^ "Mash-up makers move into the mainstream". Cnn.com. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ "Remix Without Romance: What Free Culture Gets Wrong". Copyhype.com. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ Remix Without Romance: What Free Culture Gets Wrong, Terry Hart, April 18, 2012, Copyhype.com