User:Djwilms/Dioceses of the Church of the East

At the height of its power, in the tenth century, the Assyrian Church of the East (the so-called 'Nestorian Church') had well over a hundred dioceses, stretching from Egypt to China. These dioceses were organised into six 'interior' provinces, dating back to the fifth century and aligned along the banks of the Tigris in the Church's heartland in Mespotamia, and a dozen or more 'exterior provinces'. Most of the 'exterior provinces' were located in Iran, Central Asia, India and China, testifying to the Church's remarkable eastern expansion in the Middle Ages. A number of East Syrian dioceses were also established in the towns of the eastern Mediterranean, in Palestine, Syria, Cilicia, Cyprus and Egypt.

Sources[edit]

There are few sources for the ecclesiastical organisation of the Church of the East before the Sassanian period, and the information provided in martyr acts and local histories such as the Chronicle of Erbil may not always be genuine. The Chronicle of Erbil, for example, provides a list of East Syrian dioceses in 225. References to bishops in other sources confirm the existence of many of these dioceses, but it is impossible to be sure that all of them existed at this early period. Diocesan history was a subject particularly susceptible to later alteration, as bishops sought to gain prestige by exaggerating the antiquity of their dioceses, and such evidence for an early diocesan structure in the Church of the East must be treated with great caution. Firmer ground is only reached with the fourth-century narratives of the martyrdoms of bishops during the persecution of Shapur II, which name several bishops and dioceses in Mesopotamia and elsewhere.

The ecclesiastical organisation of the Church of the East in the Sassanian period, at least in the interior provinces and from the fifth century onwards, is known in some detail from the records of synods convened by the patriarchs Isaac in 410, Yahballaha I in 420, Dadisho‘ in 424, Acacius in 486, Babaï in 497, Aba I in 544, Joseph in 554, Ezekiel in 576, Isho‘yahb I in 585, and Giwargis in 605.[1] These documents record the names of the bishops who were either present at these gatherings or who adhered to their acts by proxy or later signature. These synods also dealt with diocesan discipline, and throw interesting light on the problems which the leaders of the church faced in trying to maintain high standards of conduct among their widely-dispersed episcopate.

After the Arab conquest in the seventh century the sources for the ecclesiastical organisation of the Church of the East are of a slightly different nature from the synodical acts and historical narratives of the Sassanian period. As far as its patriarchs are concerned, reign-dates and other dry but interesting details have often been meticulously preserved. The eleventh-century Chronograpy of Eliya Bar Shinaya has recorded the date of consecration, length of reign, and date of death of all the patriarchs from Timothy I (780–823) to Yoḥannan V (1001–11), together with less exact information on Timothy's predecessors. The histories of Mari, ‘Amr and Ṣliba supply additional information, giving the historian a far better chronological framework for the Ummayad and ‘Abbasid periods than for the Mongol and post-Mongol periods.

However, rather less is known about the church's diocesan organisation at this period. Although the acts of several synods held between the seventh and thirteenth centuries were recorded (the fourteenth-century author ‘Abdisho‘ of Nisibis mentions the acts of the synods of Isho‘ Bar Nun and Eliya I, for example), most have not survived. The last synod of the Church of the East whose acts have survived in full was that of the patriarch Gregory in 605. Records of local synods convened at Dairin in Beth Qaṭraye by the patriarch Giwargis in 676 and in Adiabene in 790 by Timothy I have survived by chance, but the main sources for the Ummayad and ‘Abbasid periods are records in a number of historical works of the attendance of bishops at the consecration of successive patriarchs (in particular the histories of Mari, ‘Amr and Ṣliba). These records, patchy until the eleventh century, inevitably give prominence to the bishops of Mesopotamia and overlook those of the more remote dioceses who were unable to be present. These bishops were often recorded in the acts of the Sassanian synods, because they adhered to them by letter.

Besides such records, a number of local histories of monasteries in northern Mesopotamia were written at this period (in particular Thomas of Marga’s Book of Governors, the History of Rabban Bar ‘Idta, the History of Rabban Hormizd the Persian, the History of Mar Sabrisho‘ of Beth Qoqa and the Life of Rabban Joseph Busnaya) and these histories, together with a number of hagiographical accounts of the lives of notable holy men, occasionally mention bishops of the northern Mesopotamian dioceses.

Thomas of Marga is a particularly important source for the second half of the eighth century and the first half of the ninth century, a period for which little synodical information has survived and also few references to the attendance of bishops at patriarchal consecrations. As a monk of the important monastery of Beth ‘Abe, and later the secretary of the patriarch Abraham I (832–50), he had access to a wide range of written sources, including the correspondence of the patriarch Timothy I, and could also draw on the traditions of his old monastery and the long memories of its monks. Thirty or forty otherwise unattested bishops of this period are mentioned in the Book of Governors, and it is the only source for the existence of the northern Mesopotamian diocese of Salaḥ. A particularly important passage mentions the prophecy of the monastery’s superior Quriaqos, who flourished around the middle of the eighth century, that forty-two of the monks under his care would later become bishops, metropolitans, or even patriarchs. Thomas was able to name, and supply interesting information about, thirty-one of these bishops.

Nevertheless, references to bishops beyond Mesopotamia are infrequent and capricious. Furthermore, many of the relevant sources are in Arabic rather than Syriac, and often use a different Arabic name for a diocese previously attested only in the familiar Syriac form of the synodical acts and other early sources. Most of the Mesopotamian dioceses can be readily identified in their new Arabic guise, but on occasion the use of Arabic presents difficulties of identification.

Parthian period[edit]

By the middle of the fourth century, when many of its bishops were martyred during the persecution of Shapur II, the Church of the East probably had twenty or more dioceses within the borders of the Sassanian empire, in Beth Aramaye, ‘Ilam, Maishan, Adiabene (Syriac: Ḥdyab, ܚܕܝܐܒ) and Beth Garmaï, and possibly also in Khorasan. Some of these dioceses may have been at least a century old, and it is possible that many of them were founded before the Sassanian period. According to the Chronicle of Erbil there were several dioceses in Adiabene and elsewhere in the Parthian empire as early as the end of the first century, and more than twenty dioceses in 225 in Mesopotamia and northern Arabia, including the following seventeen named dioceses: Beth Zabdaï, Karka d'Beth Slokh, Kashkar, Beth Lapaṭ, Hormizd Ardashir, Prath d'Maishan, Ḥnitha, Ḥrbaṭ Glal, Arzun, Beth Niqator (apparently a district in Beth Garmaï), Shahrgard, Beth Meskene (possibly Piroz Shabur, later an East Syrian diocese), Ḥulwan, Beth Qaṭraye, Ḥazza (probably the village of that name near Erbil, though the reading is disputed), Dailam and Singara. The cities of Nisibis and Seleucia-Ctesiphon, it was said, did not have bishops at this period because of the hostility of the pagans towards an overt Christian presence in the towns. The list is plausible, though it is perhaps surprising to find dioceses for Ḥulwan, Beth Qaṭraye, Dailam and Singara so early, and it is not clear whether Beth Niqator was ever an East Syrian diocese.

Sassanian period[edit]

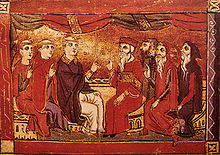

During the fourth century the dioceses of the Church of the East began to group themselves into regional clusters, looking for leadership to the bishop of the chief city of the region. This process was formalised at the synod of Isaac in 410, which first asserted the priority of the 'grand metropolitan' of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, and then grouped most of the Mesopotamian dioceses into five geographically-based provinces (by order of precedence, Beth Huzaye, Nisibis, Maishan, Adiabene and Beth Garmaï), each headed by a metropolitan bishop with jurisdiction over several suffragan bishops. Canon XXI of the synod foreshadowed the extension of this metropolitan principle to the more remote dioceses in Fars, Khorasan and elsewhere, and in the second half of the sixth century the bishops of Rev Ardashir and Merv (and possibly Herat) also became metropolitans. The new status of the bishops of Rev Ardashir and Merv was recognised at the synod of Joseph in 554, and henceforth they took sixth and seventh place in precedence respectively after the metropolitan of Beth Garmaï. During the reign of Isho‘yahb II the bishop of Ḥulwan also became a metropolitan. The system established at this synod survived unchanged in its essentials for nearly a millennium. Although during this period the number of metropolitan province increased as the church’s horizons expanded, and although some suffragan dioceses within the original six metropolitan provinces died out and others took their place, all the metropolitan provinces created or recognised in 410 were still in existence in 1318.

Province of the Patriarch[edit]

The patriarch himself sat at Seleucia-Ctesiphon or, more precisely, the Sassanian foundation of Veh Ardashir on the west bank of the Tigris, built in the third century adjacent to the old city of Seleucia, which was thereafter abandoned. Ctesiphon, founded by the Parthians, was nearby on the east bank of the Tigris, and the double city was always known by its early name Seleucia-Ctesiphon to the East Syrians. It was not normal for the head of an eastern church to administer an ecclesiastical province in addition to his many other duties, but circumstances made it necessary for Yahballaha I to assume responsibility for a number of dioceses in Beth Aramaye.

The dioceses of Kashkar, Zabe, Ḥirta, Beth Daraye and Dasqarta d'Malka (the Sassanian winter capital Dastagird), doubtless because of their antiquity or their proximity to the capital Seleucia-Ctesiphon, were reluctant to be placed under the jurisdiction of a metropolitan, and it was felt necessary to treat them tactfully. A special relationship between the diocese of Kashkar and the diocese of Seleucia-Ctesiphon was defined in Canon XXI of the synod of 410: 'The first and chief seat is that of Seleucia and Ctesiphon; the bishop who occupies it is the great metropolitan and chief of all the bishops. The bishop of Kashkar is placed under the jurisdiction of this metropolitan; he is his right arm and minister, and he governs the diocese after his death.’ Although their bishops were admonished in the acts of these synods, they persisted in their intransigence, and in 420 Yahballaha I placed them under his direct supervision. This ad hoc arrangement was later formalised by the creation of a ‘province of the patriarch’. Kashkar, by tradition an apostolic foundation, was the highest ranking diocese in the province, and its bishops enjoyed the privilege of guarding the patriarchal throne during the interregnum between one patriarch's death and the election of his successor. The diocese of Dasqarta d'Malka is not mentioned again after 424, but bishops of the other dioceses were present at most of the fifth- and sixth-century synods. Three more dioceses in Beth Aramaye are mentioned in the acts of the later synods: Piroz Shabur (first mentioned in 486); Ṭirhan (first mentioned in 544); and Shenna d'Beth Ramman or Qardaliabad (first mentioned in 576). All three dioceses were to have a long history.

Province of Beth Huzaye ('Ilam)[edit]

The metropolitan of Beth Huzaye (‘Ilam), who resided in the town of Beth Lapaṭ (Veh az Andiokh Shapur), enjoyed the right of consecrating a new patriarch. In 410 it was not possible to appoint a metropolitan for Beth Huzaye, as several bishops of Beth Lapaṭ were competing for precedence and the synod declined to choose between them. Instead, it merely laid down that once it became possible to appoint a metropolitan, he would have jurisdiction over the dioceses of Karka d'Ledan, Hormizd Ardashir (Ahwaz), Shushter and Shush (Susa). These dioceses were all founded at least a century earlier, and their bishops were present at most of the synods of the fifth and sixth centuries. A bishop of Ispahan was present at the synod of Dadisho‘ in 424, and by 576 there were also dioceses for Mihraganqadaq (probably the 'Beth Mihraqaye' included in the title of the diocese of Ispahan in 497) and Ram Hormizd.

Province of Nisibis[edit]

In 363 the Roman emperor Jovian was obliged to cede Nisibis and the surrounding districts to Persia to extricate the defeated army of his predecessor Julian from Persian territory. The Nisibis district, after nearly fifty years of rule by Constantine and his Christian successors, may well have contained more Christians than the entire Sassanian empire, and this Christian population was absorbed into the Church of the East in a single generation. The impact of the cession of Nisibis on the demography of the Church of the East was so marked that the province of Nisibis was given the second rank among the five metropolitan provinces established at the synod of Isaac in 410, a precedence apparently conceded without dispute by the bishops of the three older Persian provinces relegated to a lower rank.

The metropolitan of Nisibis was 'metropolitan of Arzun, of Qardu, of Beth Zabdaï, of Beth Raḥimaï and of Beth Moksaye, and of the bishops to be found there'. The dioceses of Arzun, Qardu and Beth Zabdaï were to enjoy a long history, but Beth Raḥimaï is not mentioned again, while Beth Moksaye is not mentioned after 424, when its bishop Atticus (perhaps a Greek) subscribed to the acts of the synod of Dadisho‘. Besides the bishop of Arzun, a bishop of 'Aoustan d’Arzun' (plausibly identified with the district of Ingilene) also attended these two synods, and his diocese was one of the six assigned to the province of Nisibis. The diocese of Aoustan d'Arzun seems to have survived into the sixth century. By 497 a diocese had also been established at Balad (the modern Eski Mosul) on the Tigris, which lasted into the fourteenth century, and by 585 there was a diocese for Kartwaye. A bishop Arṭashahr of Armenia was present at the synod of Dadisho‘ in 424. By the fourteenth century Armenia was a suffragan diocese of the province of Nisibis, and before that in the province of Mosul (the inheritor of the old province of Adiabene), but during the Sassanian period the diocese does not seem to have been assigned to a metropolitan province. The bishops of Armenia appear to have sat at the town of Ḥalaṭ (Aḥlaṭ) on the northern shore of Lake Van.

Province of Maishan[edit]

In southern Mesopotamia, the bishop of Prath d'Maishan became metropolitan of Maishan in 410, responsible also for the three suffragan dioceses of Karka d'Maishan, Rima and Nahargur. The bishops of these four dioceses attended most of the synods of the fifth and sixth centuries.

Province of Adiabene[edit]

The bishop of Erbil became metropolitan of Adiabene in 410, responsible also for the six suffragan dioceses of Beth Nuhadra, Beth Bgash, Beth Dasen, Ramonin, Beth Mahqart and Dabarin. Bishops of the dioceses of Beth Nuhadra, Beth Bgash and Beth Dasen, which covered the modern ‘Amadiya and Hakkari regions, were present at most of the early synods, and the three dioceses continued without interruption into the thirteenth century. The other three dioceses are not mentioned again. By the middle of the sixth century there were also dioceses in the province of Adiabene for Ma‘altha and Nineveh. The diocese of Ma‘altha (probably the town associated with the Ḥnitha or Zibar district to the east of ‘Aqra rather than Ma‘altha in Beth Nuhadra) is first mentioned in 497, and the diocese of Nineveh in 554, and bishops of both dioceses attended most of the later synods.

Province of Beth Garmaï[edit]

The bishop of Karka d'Beth Slokh (modern Kirkuk) became metropolitan of Beth Garmaï, responsible also for the five suffragan dioceses of Shahrgard, Lashom, Maḥoze d'Arewan, Radani, and Ḥrbaṭ Glal. Bishops from these five dioceses are found at most of the synods in the fifth and sixth centuries. Two other dioceses also existed in the Beth Garmaï district in the fifth century which do not appear to have been under the jurisdiction of its metropolitan. A diocese existed at Taḥal as early as 420, which seems to have been an independent diocese until just before the end of the sixth century, and bishops of the Karme district on the west bank of the Tigris around Tagrit, in later centuries a West Syrian stronghold, were present at the synods of 486 and 554.

The exterior provinces[edit]

Canon XXI of the synod of 410 provided that 'the bishops of the more remote dioceses of Fars, the Islands, Beth Madaye [Hamadan], Beth Raziqaye [Rai] and also the country of Abrashahr [the district around Tus], must later accept the definition established in this council.' This reference demonstrates that the influence of the Church of the East in the fifth century had gone beyond the non-Iranian fringes of the Sassanian empire to include several districts within Iran itself, and had also spread southwards to the islands off the Arabian shore of the Persian Gulf, which were under Sassanian control at this period. By the middle of the sixth century the influence of the Church of the East appears to have spread beyond the frontiers of the Sassanian empire, as a passage in the acts of the synod of Aba I in 544 refers to East Syrian communities 'in every district and every town throughout the territory of the Persian empire, in the rest of the East, and in the neighbouring countries'.[2]

Fars and the Persian Gulf[edit]

There were at least eight dioceses in Fars and the islands of the Persian gulf in the fifth century, and probably eleven or more by the end of the Sassanian period. In Fars the diocese of Rev Ardashir is first mentioned in 420, the dioceses of Ardashir Khurrah (Shiraf), Darabgard, Istakhr, and Kazrun (Shapur or Bih Shapur) in 424, and a diocese of Qish in 540. On the Arabian shore of the Persian Gulf dioceses are first mentioned for Dairin and Mashmahig in 410 and for Beth Mazunaye (Oman) in 424. By 540 the bishop of Rev Ardashir had become a metropolitan, responsible for the dioceses of both Fars and Arabia. A fourth Arabian diocese, Hagar, is first mentioned in 576, and a fifth diocese, Ḥaṭṭa (previously part of the diocese of Hagar), is first mentioned in the acts of a regional synod held on the Persian Gulf island of Dairin in 676 by the patriarch Giwargis to determine the episcopal succession in Beth Qaṭraye, but may have been created before the Arab conquest.

Khorasan and Segestan[edit]

Khorasan and Segestan had at least four East Syrian dioceses in the fifth century. A diocese clearly already existed for Abrashahr by 410, and bishops of Merv, Abrashahr, Herat and Segestan were present at the synod of Dadisho‘ in 424. The bishop of Merv was named Bar Shaba, 'son of the deportation', suggesting that Merv's Christian community may have been deported from Roman territory. Four other dioceses appear briefly during the sixth century. Bishops of 'Abiward and Sahr-i Peroz' and of Merw-i Rud were present at the synod of Joseph in 554, and bishops of Pusang and of 'Badisi and Qadistan' at the synod of Isho‘yahb I in 585. They are not mentioned again. The bishop of Merv was recognised as a metropolitan at the synod of Joseph in 554, and a metropolitan of Herat was present at the synod of Isho‘yahb I in 585. The diocese of Segestan was disputed during the schism of Narsaï and Elisha‘, and the patriarch Aba I resolved the dispute in 544 by temporarily dividing the diocese, assigning Zarang, Farah and Qash to the bishop Yazdaphrid, and Bist and Rukut to the bishop Sargis.

Media and Rai[edit]

In western Iran, bishops of Beth Madaye [Hamadan] are first mentioned in 486, but the diocese of Hamadan was clearly already in existence in 410. A bishop of 'the deportation of Beth Lashpar' was present at the synod of Dadisho‘ in 424, and bishops of Beth Lashpar (Ḥulwan) attended the later synods of the fifth and sixth centuries. A bishop of the nearby locality of Masabadan was present at the synod of Joseph in 554.

In northern Iran, a bishop of Beth Raziqaye (Rai) is first mentioned in 424, but the diocese clearly existed by 410. Dioceses are found for 'Ganzak and Adarbaigan' from 486 onwards, and for Paidangaran around the middle of the sixth century. A bishop of 'Amol and Gilan' was present at the synod of Joseph in 554. An East Syrian diocese was also established in the Gurgan district to the southeast of the Caspian Sea in the fifth century for a community of Christians deported from Roman territory. A bishop named Domitian 'of the deportation of Gurgan' was present at the synod of Dadisho‘ in 424, and another bishop of Gurgan was present at the synod of 497.

Unlocalised dioceses[edit]

Several dioceses mentioned in the acts of the early synods cannot be convincingly localised.

The bishop Ardaq of 'Mashkena d’Qurdu' was present at the synod of Dadisho‘ in 424.[3]

The bishop Mushe of 'Hamir' was present at the synod of Acacius in 486.

The bishops Paul, Samuel and Paul of 'Barḥis' were present respectively at the synods of Joseph in 544, Ezekiel in 576, and Gregory in 605.[4]

The bishop Bar Sahde of ‘Aïn Sipne was present at the synod of Ezekiel in 576.[5]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

Chabot, Synodicon Orientale