User:Emmaramsden/sandbox

The House of Augustus, or the Domus Augusti, is the first major site upon entering the Palatine Hill in Rome, Italy. Historically, this house has been identified as the primary place of residence for the emperor Augustus.[1] The Domus Augusti is located near the so-called Hut of Romulus and other sites that have connections to the foundation of Rome. This residence contained a complex of structures, and the Temple of Apollo Palatinus.The bottom floor is not accessible today, but it is possible to make out the basin of a fountain and the rooms beyond it that were paved in coloured marble.[2]

The Domus Augusti should not be confused with the nearby Domus Augustana, part of the vast palatial complex constructed by Emperor Domitian on the Palatine in 92 CE.[3]

Excavations[edit]

In 1865, Pietro Rosa began excavations at what is now called the House of Livia. His excavations, part of a larger program commissioned by Napolean III, included a superficial excavation of the Domus Augusti, located to the south.In 1937, Alfonso Bartoli did further surveys of the area and found archaeological remnants of collapsed vaults. [4] In 1956, extensive excavations began under Gianfilippo Carettoni. His initial excavations revealed a structure, comprised of a set of rooms, which have now been identified as part of a larger complex known as Peristyle A. He attributed this structure to Augustus based on its proximity to the nearby Temple of Apollo.[5] In the early years of 2000, further work was done led archaeologists to posit that the original Peristyle was part of a much larger house.[6] A restoration program, said to have cost almost two million euros, was completed in 2008, giving the public access to the rooms excavated by Gianfilippo Carettoni.[7]

Literary Evidence[edit]

The House of Augustus is heavily attested in the extant ancient literary sources. Suetonius' work indicates that Octavian moved into the House of Hortentius on the Palatine, relocating from his original home in the Roman Forum.[8] Velleius reports that after, Octavian began to purchase the land surrounding the House of Hortentius.[9] Soon after, this spot was struck by lightning, and so Octavian declared this a public property and dedicated a temple to Apollo, known as the Temple of Apollo Palatinus, as Apollo had helped Augustus in his victory over Sextus Pompey in 36 BCE.[10] And because of this pious act, as Cassius Dio states, the senate decreed that the property around this area should be given to Augustus from public funds.[11] The oak crown, said to have adorned the front door, was a tribute to this senatorial dedication in 27 BCE.[12][13] The house was destroyed in a fire in 3 CE.[14][15]

Archaeological Evidence[edit]

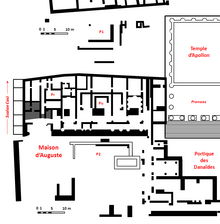

The plan of the site comprises of a series of rooms in sections built at various times, built from tufa blocks of opus quadratum. It has two peristyle style courts that are bordered by small rooms. The monument was two-stories, terraced complex. Between each peristyle sits the Temple of Apollo Palatinus. Most of the archaeological evidence that survives is derived from Peristyle A, as much of Peristyle B was destroyed by the later Palace of Domitian. This entire site occupies ca. 8,600 m².

Carrettoni House[edit]

Excavated and initially identified as the House of Augustus by G. Carettoni, this structures comprises the northern rooms adjacent to Peristyle A. The structure consists of two rows of rooms built in opus quadratum, divided into an eastern and western section.

The rooms to the western side of this complex may have been designated as the private living quarters. These rooms consist of extensive wall decoration and paintings. One room, known as the Room of the Masks, features persective architectural paintings and theatrical masks, typical of the Second Style of Roman wall painting. Another room features bows of pine, very similar to the House of Livia.[16] These two rooms date to 30 BCE.[17]

The eastern rooms encircled a large central room, which was open toward the south, and perhaps served a public function. These rooms were decorated with geometric floor mosaics. of this house have extensive decoration, including geometric floor mosaics and wall paintings.[18]

G. Carettoni, who identified the whole structure as the House of Augustus, attached it to the Temple of Apollo through an entranceway [19] Recent excavations have shown that these rooms were filled in and partially destroyed in 30 BCE in order to build the Temple of Apollo Palatinus, and this entranceway has now been posited as a staircase to a second level instead.[20]

I. Iacopi and G. Tedone suggest that this was part of the original house of Hortentius purchased by Augustus. After building a temple to Apollo, in which he destroyed some of these rooms, he reconfigured his villa, and built a large Peristyle (Peristyle A) and rooms overtop of the Carettoni house.[21] On the other hand, A. Carrandini and D. Bruno suggested that the Carretoni house and rooms were part of an earlier villa, that was incorporated into the later Peristyle.

Peristyle A[edit]

This peristyle sits just west of the Temple of Apollo. It dates to approximately 39 BCE and has been identified as the private quarters of the villa. There is little archaeological evidence that remains, with the exception of a portion of the tufa peristyle. [22]

Peristyle B[edit]

Scholars have suggested a symmetrical plan of the entire complex, in which a peristyle (Peristyle B) complex sits in a symmetrical position across on the other side of the Temple, and was constructed between 39 and 36 BCE. It perhaps served a public function.[23] However, there is little archaeological evidence to support this hypothesis, as the construction of the Palace of Domitian, also known as the Domus Augustana, has disturbed much of this area on the Palatine. It has been suggested by some scholars that this was how the Domus Augustana received its name.[24]

Temple of Apollo Palatinus[edit]

Initially identified as the Temple of Jupiter Victor, the Temple of Apollo is located between both peristyles, on a higher terrace. It was finished in 28 BCE, confirmed by the findings of Republican houses underneath it. The podium was 24 m by 45 m, and the Temple featured barrel vaults and Corinthian capitals. Built of Luna marble and concrete, it housed the cult statues of Apollo, Diana and Latona, in addition to the Sibylline books.[25]

Issues of Identification[edit]

The house was described as modest by Suetonius, who noted that Augustus had a great disdain for the lavish lifestyle. This is attested in his promotion of anti-sumptuary laws, where he placed limits on private building projects.[26] These literary accounts have ignited debates over the identification of this monument in recent years, and scholars are divided. Carettoni, having only partially excavated the area, classified the structure as being restrained in elegance and decor.[27] Since further excavation revealed a very large villa plan, Andrea Carandini is inclined to doubt the statement of Suetonius.[28] Other scholars have instead suggested that this villa would have been too luxurious and large to the House of Augustus that is described in the literary sources.[29][30]

References[edit]

- ^ Tomei, Maria Antonietta. The Palatine. Trans. Luisa Guarneri Hynd. Milano: Electa, 1998. Print.

- ^ [Simonis, Damien. Lonely Planet Italy. 8th ed. Oakland: Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd, 2008.]

- ^ Richardson, Lawrence. "Domus Augstana" From A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1992. Print.

- ^ Hall, Jonathan (2014). Artifact & Artifice: Classical Archaeology and the Ancient Historian. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 168-170.

- ^ Carettoni, Gianfilippo (1967). "I problemi della zona augustea del Palatino alla luce dei recenti scavi". AttiPont Acc. 38: 61-64.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ Iacopi, I.; Tedone, G. (2006). "Bibliotheca e Porticus ad Apollinis". MDAI. 112: 352-355.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ Hall, Jonathan (2009). Artifact & Artifice: Classical Archaeology and the Ancient Historian. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 168.

- ^ Suetonius. Life of Augustus 72.

- ^ Velleius. The Roman History 2.

- ^ Suetonius. Life of Augustus.

- ^ Cassius Dio. Roman History 73.

- ^ Ovid. Fasti I.

- ^ Cassius Dio. Roman History 53.

- ^ Suetonius. Life of Augustus 57.

- ^ Cassius Dio. Roman History 55.

- ^ Hall, Jonathan (2014). Artifact & Artifice: Classical Archaeology and the Ancient Historian. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 176.

- ^ Coarelli, Filippo (2014). Rome and Environs. London: University of California Press. p. 141.

- ^ Coarelli, Filippo (2014). Rome and Environs. London: University of California Press. p. 140.

- ^ Carettoni, Gianfilippo (1967). "I problemi della zona augustea del Palatino alla luce dei recent scavi". AttiPontAcc. 38: 61-64.

- ^ Hall, Jonathan (2014). Artifact & Artifice: Classical Archaeology and the Ancient Historian. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 181.

- ^ Iacopi, Irene; Tedone, Giovanna (2006). "Bibliotheca e Porticus ad Apollinis". MDI. 112: 366-371.

- ^ Carandini, Andrea; Bruno, Daniela (2008). La casa di Augusto dai "Lupercalia" al Natale. Rome: Laterza. p. 30-31.

- ^ Carandini, Andrea; Bruno, Daniela (2008). La casa di Augusto dai "Lupercalia" al Natale. Rome: Laterza. p. 192-194.

- ^ Coarelli, Filippo (2014). Rome and Environs. London: University of California Press. p. 142.

- ^ Coarelli, Filippo (2014). Rome and Environs. London: University of California Press. p. 143.

- ^ Gelleius. Noctes Atticae 2.22.

- ^ Carettoni, Gianfilippo (1967). "I problemi della zona augustea del Palatino alla luce dei recenti scavi". AttiPont Acc. 38: 61.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ Carandini, Andrea; Bruno, Daniela (2008). La casa di Augusto dai "Lupercalia" al Natale. Rome: Laterza. p. 83-84.

- ^ Iacopi, I.; Tedone, G. (2006). "Bibliotheca e Porticus ad Apollinis". MDAI. 112: 352-355.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ Hall, Jonathan (2009). Artifact & Artifice: Classical Archaeology and the Ancient Historian. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 168.

41°53′18″N 12°29′12″E / 41.88833°N 12.48667°E

The Saepta Julia was a building in the Campus Martius of Rome, where citizens gathered to cast votes. The building was conceived by Julius Caesar and dedicated by Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa in 26 BCE. The building replaced an older structure, called the Ovile, built as a place for the comitia tributa to gather to cast votes.[1] The Saepta Julia can be seen on the Forma Urbis Romae, a map of the city of Rome as it existed in the early 3rd century CE. Part of the original wall of the Saepta Julia can still be seen right next to the Pantheon.

History[edit]

The conception of the Saepta Julia, which also goes by Saepta or Porticus Saeptorum, began during the reign of Julius Caesar (died 44 BC). The quadriporticus (four-sided portico, like the one used for the enclosure of the Saepta Julia) was an architectural feature made popular by Caesar.[1]

After Caesar's assassination in 44 BCE, work continued on projects that Caesar had set into motion.[2] Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, who used to support Caesar and subsequently aligned with his successor Octavian, took on the continuation of the Saepta Julia building project. The building was finally completed and dedicated by Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa in 26 BCE. Agrippa also decorated the building with marble tablets and Greek paintings.[3]

The Great Fire of Rome led to its destruction in 80 CE, and was rebuilt sometime before the reign of Domitian.[4] Restoration also took place under Hadrian, as is evidenced by brick-work and literary sources.[5] The building is also attested on a post-Constantine bronze collar of a slave, but there is no known mention of the building in the Middle Ages.[6]

Plan[edit]

Due to the limited archaeological remains, the majority of archaeological reconstructions are derived from the Forma Urbis Romae and corresponding literary sources. Located on the Campus Martius, between the Baths of Agrippa and the Serapeum, the Saepta Julia was a rectangular porticus complex, which extended along the west side of the Via Lata to the Via di S. Marco. It was 310 meters long by 120 meters wide and was built of travertine marble. Two porticoes lay on the east and west of the complex. The north end was a lobby, and the south side connected to the Diribitorium through an uncolonnaded, broad corridor. The only entrances that have been discerned are minor entrances on the south end of the complex.[7]

Archaeological excavations underneath the Palazzo Doria uncovered multiple travertine piers. While the majority of the piers measured 1.7 meters square, other piers showed a variety of dimension. This has led some scholars to speculate on the existence of a second floor.[8][9]

The Saepta was supplied with water by Aqua Virgo, which supplied the majority of buildings on the Campus Martius.[10]

Porticus Argonautarum[edit]

The Porticus Argonautarum lined the western side of the Saepta Julia. It was completed by Agrippa ca. 25 BCE, and received its name from the artwork it depicted, which showed Jason and the Argonauts. A portion of the western wall survives, and is located beside the Pantheon, and suggests that it was made of brick-faced concrete, and covered in marble.[11] Reconstructed by Domitian after the fire of 80 CE, this portico was also part of Hadrian's reconstruction of the entire Saepta Julia.[12]

Porticus Meleagri[edit]

The Porticus Meleagri lined the eastern side of the Saepta Julia. Little remains of the Porticus Meleagri, and location and reconstruction rely primarily on the Forma Urbis Romae. Although not mentioned, tt was most likely constructed during the final decades of the first century BCE, along with the dedication of the Saepta.

Use[edit]

The concept of the Saepta was initially planned by Caesar in place of the earlier Ovile, and was projected as early as 54 BCE, and finished by Agrippa in 26 BCE. In a letter to Atticus, Cicero writes that the building was to be made of marble, with a lofty portico and a roof.[13]

The building was initially intended to be used as a voting place for both the comitia centuriata and the comitia tributa.[14] However, with the diminishing importance of the voting comitias from the Augustan period onward, the building began to be repurposed. Gladiatorial combats were exhibited during the period of Augustus, and the building was also used by the senate as a meeting point.[15]

When Tiberius returned from Germany, after his military procession, he was presented in this building by Augustus.[16] While both Augustus and Caligula used this building for naumachiae.[17] It was used for gymnastics competitions and exhibitions during the reign of Nero.[18] And both Statius and Martial report that it was used intermittently as a public space for Roman citizens, as well as a market for luxury goods.[19][20]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth (eds.), The Oxford Classical Dictionary (1996) — ISBN 0-19-866172-X ; available online for a fee

- ^ Cic. Att 4.16.14

- ^ Jacobs II, Paul W.; Conlin, Diane Atnally (2015). Campus Martius: The Field of Mars in the Life of Ancient Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 107.

- ^ Statius. Silvae 4.5.2.

- ^ Historia Augusta: Life of Hadrian.

- ^ Platner, Samuel; Ashby, Thomas (1929). A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. London: Oxford University Press. p. 460.

- ^ Richardson Jr., Lawrence (1992). A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

- ^ Platner, Samuel; Ashby, Thomas (1929). A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. London: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Richardson Jr., Lawrence (1992). A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. Baltimore: John Hopkins University.

- ^ Harry, Evans (1997). Water Distribution in Ancient Rome: The Evidence of Frontinus. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. p. 109.

- ^ Richardson Jr., Lawrence (1992). A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. pp. 312–340.

- ^ Boatwright, Mary (1987). Hadrian and the City of Rome. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 51.

- ^ Cicero. Letters to Atticus 2.

- ^ Lanciani, Rodolfo (1897). The Ruins and Excavations of Ancient Rome: A Companion for Students and Travelers. New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company. p. 472.

- ^ Suetonius. Life of Augustus 23.

- ^ Suetonius. Life of Tiberius 17.

- ^ Suetonius. Life of Caligula 18.

- ^ Suetonius. Life of Nero 12.

- ^ Statius. Silvae 4.2.6.

- ^ Martial. Epigrams 2.14.5.

Category:Ancient Roman buildings and structures in Rome Category:Roman archaeology Category:Augustan building projects Category:Buildings and structures completed in the 1st century BC