User:Frutti di Mare/Sandbox

London in 1666[edit]

London was by a huge margin the largest city in Britain at this time, estimated at 300,000 inhabitants[1] or 10% of the population of the entire country.[2] It was the third largest metropolis in the western world, after Constantinople and Paris. Compared to these two capitals, London was architecturally a poor relation, a "wooden, northern, and inartificial congestion of Houses,"[3] as John Evelyn called it in 1659. By the word "inartificial", Evelyn meant unplanned, artless: London had been growing organically for seven centuries and was essentially medieval in its street plan, a warren of narrow, winding alleys. Its rapid population increase was being accommodated by outward growth, into suburbs beyond the old Roman wall, as well as by a rising inward pressure of overcrowding on the City proper. Most of the inhabitants lived in the suburbs. Only 80,000 people are believed to have been living in the City itself,[4] a crime-ridden, filthy 330-acre (1.3 km²) "congestion of Houses" bounded by the city wall to the east, north, and west, and by the river Thames to the south.[5] People of means shunned the City as far as possible, especially after a devastating outbreak of bubonic plague in the "Plague Year" of 1665.

Political tensions between the Crown and the City contributed to the disastrous course of the Great Fire. London was a hub of trade and commerce, dominated by the trading middle classes—the "citizens" of the "city"— and literally ruled by commerce, through the Court of Aldermen (presided over by the Lord Mayor) and the Court of Common Council. The franchise for these bodies was effectively limited to members of the Livery Companies, descendants of the once powerful medieval craft guilds. The economic power of the Livery Companies had declined since the Middle Ages, but politically they still ran the capital.[6] During the Civil War and Commonwealth period, which had ended only six years earlier, the City of London had been a . Charles I had been executed in the City in 1649, and the relationship between his son Charles II and the citizens was gingerly and tense. A tactful deference to the autonomy of the local government was necessarily one of Charles's first political principles.[7] Vital time was lost at the beginning of the fire, as the Lord Mayor Sir Thomas Bloodworth failed to take any decisions about house demolitions, while the King deferred to his authority. The King's brother James, Duke of York promptly offered to send the Royal Life Guards to organise and assist the firefighting effort, but the idea of ordering Royal troops into the City was difficult for Bloodworth to countenance, and he declined.[8] A few hours later, after being warned of the scale of the unfolding disaster by Samuel Pepys, Charles and James went downriver from Whitehall in the Royal barge to inspect the damage. Having done so, the King daringly overrode the authority of Bloodworth (who had gone home to sleep), ordered wholesale demolitions round the fire to create firebreaks, and sent in the Coldstream Guards. By then, however, 18 hours after the outbreak in the bakery, the house fire had become a raging firestorm which defeated such efforts.

Previous fires, especially 1632.

Architecture and materials[edit]

London was largely a timbered medieval city with winding narrow streets and the houses close together, the only exception being the stone mansions of the merchants and wealthy tradesmen, which stood spaciously apart in the central area of the city.[9] The inner ring of poorer parishes around this wealthy centre (see map [insert map tracing poorer and richer districts]) was a mix of workplaces and overcrowded housing. Many of the workplaces were fire hazards — foundries, smithys, glassmakers — which were theoretically illegal in the city, but regulations were not enforced.[10] The human habitations were crowded to bursting, with every inch of building space used to accommodate London's rapidly growing population.

Building with wood in London and using thatch as a roofing material had been prohibited for centuries, and yet these cheap materials continued to be used.[11] Charles II issued a proclamation in 1661 requiring new buildings to be made of brick or stone, and forbidding overhanging windows and "jetties". Jetties, projecting upper stories, were a particularly risky feature of the typical London house. Most houses were six or seven stories high and narrow at ground level, but maximized their use of a given ground area by "encroaching", as a contemporary observer put it, on the street with the gradually increasing size of their upper storeys. The fire hazard posed when the top jetties all but met across the narrow alleys was well perceived — "as it does facilitate a conflagration, so does it also hinder the remedy"[12] — but "the covetousness of the citizens and connivancy [that is, the corruption] of Magistrates" worked in favour of jetties. The Royal proclamation was largely ignored by the famously Republican London magistrates, who were jealous of their independence and prestige after the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660. Charles' next, sharper, message in 1665 warned of the risk of fire from the narrowness of the streets and authorized imprisonment of recalcitrant builders and demolition of dangerous buildings. It too had little impact.

The poorest districts along the riverfront were a key area for the development of the Great Fire. The river offered both hope of escape by boat, water for the firefighting effort, and, with its stores of combustibles, the highest conflagration risk of any. The crumbling wooden tenements and tar paper shacks of the poor[13] were shoehorned amongst "old paper buildings and the most combustible matter of Tarr, Pitch, Hemp, Rosen, and Flax which was all layd up thereabouts."[14] London was also full of gunpowder (black powder), especially the riverfront. Much of it was left in the homes of private citizens since the Civil War, the former members of Cromwell's New Model Army still retaining their muskets and the powder to load them with. Five to six hundred tons of powder were stored in the Tower of London at the north end of London Bridge. The ships' chandlers along the wharves also held large stocks, stored in wooden barrels.[15]

London Bridge, the only connector of the City with the south side of the Thames, was itself lined with houses and had been noted as a deathtrap in the fire of 1632. By dawn on the Sunday these houses were burning, and Pepys, observing the conflagration from the Tower of London, recorded great concern for friends living on the bridge. The threat of the destruction spreading to Southwark on the south bank was only averted by an open space between buildings on the bridge, which acted as a firebreak.[16]

The medieval wall enclosing the city put the fleeing homeless at risk of being shut into the inferno. Once the riverfront was on fire and the escape route by boat cut off, the only way out was through the narrow gates in the wall. During the first couple of days, few people had any notion of fleeing the burning city altogether; they would remove what they could carry of belongings to the nearest "safe house", in many cases the parish church, or the precincts of St. Paul's Cathedral, only to have to move again hours later. Some moved their belongings and themselves "four and five times" in a single day.[17] The perception of a need to get beyond the walls only took root on [the what-day?], and then there were near-panic scenes at the gates as distraught refugees all tried to get out with bundles, carts, wagons, and frightened horses.

The key factor in frustrating firefighting efforts was the narrowness of the streets. Even under normal circumstances, major traffic jams were of daily occurrence. During the fire, the winding, cobbled passages were additionally blocked by refugees camping in them amongst their rescued belongings, or escaping outwards, away from the centre of destruction, while demolition teams and fire engine crews tried vainly to move in towards it.

17th-century firefighting[edit]

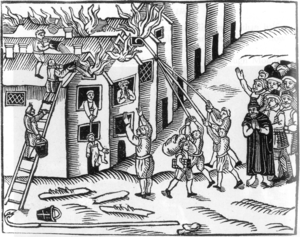

Fires were common in the crowded wood-built city with its open fireplaces, candles, ovens, and stores of combustibles. There was no police or fire department to call, but community procedures were in place for dealing with emergencies, and were usually effective. Watching for fire in the night was one of the jobs of the watch, a thousand watchmen or "bellmen" provided by the city to patrol the streets at night.[18] Public-spirited citizens would be alerted to a dangerous house fire by muffled peals on the church bells, and would congregate hastily to use the available techniques which relied, as now, on demolition and water. By law, the tower of every parish church held equipment for these efforts: long ladders, leather buckets, axes, and "firehooks" (see illustration right).[19]

Pulling down the houses downwind of a dangerous fire by means of firehooks was often an effective way of containing the danger. This time, however, demolition was crucially delayed for some hours by the Mayor's lack of leadership.[20] By the time orders came directly from the King to "spare no houses", the demolition workers with their cumbersome gear could no longer get through the narrow streets, impassably packed with refugees going the other way, carrying their belongings, dragging the sick still in their beds, and camping in all open spaces.

The use of water was also frustrated. In principle, water was available from a system of elm pipes which supplied some 30,000 houses via a high water tower at Cornhill, filled from the river at high tide, and also via a reservoir of Hertfordshire spring water in Islington.[21] It was often possible to open a pipe near a burning building and connect it to a hose to play on a fire, or fill buckets from it. Additionally, Pudding Lane was close to the river itself. Theoretically, all the lanes up to the bakery and adjoining buildings from the river should have been manned with double rows of firefighters passing full buckets up to the fire and empty buckets back down to the river. This did not happen, or at least was no longer happening by the time Pepys viewed the fire from the river at mid-morning on the Sunday. Pepys comments in his diary on how nobody was trying to put it out, but instead fleeing from it in fear, hurrying "to remove their goods, and leave all to the fire". The flames crept towards the riverfront with little interference from the overwhelmed community and soon torched the flammable warehouses along the wharves. The resulting conflagration not only cut off the firefighters from the immediate water supply of the river, but also set alight the water wheels under London Bridge which pumped water to the Cornhill water tower; the direct access to the river and the supply of piped water failed together.

London possessed advanced firefighting technology in the form of fire engines, which had been used in earlier large-scale fires. However, unlike the useful firehooks, these large pumps had rarely proved flexible or functional enough to make much difference. Only some of them had wheels, others were mounted on wheelless sleds.[22] They had to be brought a long way, tended to arrive too late, and, with spouts but no delivery hoses, had limited reach.[23] On this occasion an unknown number of fire engines were either wheeled or dragged through the narrow, cobbled streets, some from across the city, against the human current of fleeing homeless. The piped water that they were designed for had already failed, but parts of the river bank could still be reached. As gangs of men tried desperately to maneouvre the engines right up to the river to fill their reservoirs, several of the engines toppled into the Thames. The heat from the flames was by then too great for the remaining engines to get within a useful distance; they couldn't even get into Pudding Lane.

- Hic est lacuna about Charles and James going downriver to see the fire--to see Charles I avenged? (Hanson 139) Reddaway: Charles was a hero, putting the equally brilliant Duke of York in supreme command (first time I've heard any good of James' efficiency or smarts!), helping out personally in the firefighting effort, "dismounting to handle the buckets like any labourer" (25). Then Charles saved the whole refugee effort by providing tents for them (O RLY? where did tents come from? the army must have been using theirs) and issuing proclamations ordering neighboring parishes to provide lodging, and the privileged Corporate Towns to allow the refugees to come there and pursue their trades. 25-27.

Course of the fire[edit]

After two rainy summers in 1664 and 1665, London had lain under an exceptional drought ever since November 1665, and the wooden buildings were tinder-dry after the long hot summer of 1666. The bakery fire in Pudding Lane spread at first due west, fanned by a high eastern gale.

Sunday, September 2[edit]

A fire broke out at Thomas Farriner's bakery in Pudding Lane a little after midnight on September 2.[24] The family were trapped upstairs but managed to climb from an upstairs window to the house next door, except a maidservant who was too frightened to try, and became the first victim.[25] The neighbours tried to help put out the fire, and after an hour the parish constables arrived and judged that the adjoining houses had better be demolished to prevent further spread. The householders protested, and the Lord Mayor Sir Thomas Bloodworth, who had the authority to override their wishes, was sent for. When Bloodworth arrived, the flames were consuming the adjoining houses and creeping towards the riverfront with its warehouses and huge amounts of flammable goods. The more experienced firefighters were clamoring for houses to be pulled down, but Bloodworth refused, as most premises were rented and the owners couldn't be found. Pressed, he made the often-quoted remark "A woman could piss it out", and left.

On Sunday morning, Samuel Pepys climbed the Tower of London to get an aereal view of the fire, and records in his diary that the easterly gale had turned it into a conflagration.[26] It had burned down several churches and reached the Thames riverfront with its flammable warehouses. The houses lining London Bridge were burning. Taking a boat to inspect the destruction at close range, Pepys describes a "lamentable" fire, "everybody endeavouring to remove their goods, and flinging into the river or bringing them into lighters that layoff; poor people staying in their houses as long as till the very fire touched them, and then running into boats, or clambering from one pair of stairs by the water-side to another." A mile downriver by Parliament Stairs, young William Taswell who had bolted from the early morning service in Westminster Abbey saw some of these "objects of distress" arrive, unclothed and covered only with blankets, in for-hire lighter boats. The services of the lightermen had suddenly become extremely expensive, and only the lucky ones were able to secure a place. Pepys continued upriver to the court at Whitehall, "where people come about me, and did give them an account dismayed them all, and word was carried in to the King. So I was called for, and did tell the King and Duke of Yorke what I saw, and that unless his Majesty did command houses to be pulled down nothing could stop the fire. They seemed much troubled, and the King commanded me to go to my Lord Mayor from him, and command him to spare no houses, but to pull down before the fire every way." Charles's brother James, Duke of York, offered the use of the Royal Life Guards to help fight the fire.

The fire leapt easily from building to building in the high wind, and as soon as people started fleeing from it rather than trying to put it out, which happened at mid-morning on the Sunday, their moving human mass and their bundles and carts made the lanes impassable for firefighters going in the opposite direction with their cumbersome gear, and for all carriages. Pepys took a coach back into the city from Whitehall, but got only as far as St. Paul's Cathedral before he had to get out and walk. Smaller wagons and handcarts with goods were still on the move, and the sick were hauled through the streets in their beds. Most people walked, heavily weighed down. The parish churches that were not directly threatened were filling up with furniture and valuables, which would soon have to be moved further afield. Pepys found Mayor Bloodworth trying to coordinate the firefighting efforts and near collapse, "like a fainting woman", crying out plaintively in response to the King's message that he was pulling down houses. "But the fire overtakes us faster then we can do it." Holding on to his civic dignity, he refused James's offer of soldiers, and then he went home.[27]

The King and his brother sailed down from Whitehall to view the destruction, and found that houses still weren't being pulled down in spite of Bloodworth's assurances to Pepys. Taking the risk of overriding the Mayor's authority, Charles put Alderman Sir Richard Browne in charge of demolition and, ignoring Bloodworth's refusal to ask for troops, sent in the Coldstream Guards "to be more particularly assisting to the Lord Mayor and Magistrates."[28]

By Sunday afternoon, some 18 hours after the alarm was raised in Pudding Lane, the fire had become a firestorm which created its own weather. A tremendous uprush of hot air above the flames, superspeeded by the chimney effect wherever constrictions such as jettied buildings narrowed the air current, left a vacuum at ground level. The resulting strong inward winds did not tend to put out the fire, as might be thought;[29] instead, the tremendous turbulence created by the uprush made the wind veer erratically both north and south of the main, easterly, direction of the gale which was still blowing.

Monday, September 3[edit]

The two wind systems added fresh oxygen to the flames and combined to push them in a more northerly direction, up into the centre of the City.[30] The corresponding push to the south was in the main halted by the river itself, but had torched the houses on London Bridge and was threatening to cross the bridge and endanger the borough of Southwark on the other side. The south riverbank was saved, just as it had been in the latest major city fire of 1632, by a pre-existent firebreak, a long gap between the houses, one third of the way across the bridge. By dawn on Monday, the fire was principally expanding north and west. Several observers emphasize the despair and helplessness which seemed to seize the Londoners on this second day, and the lack of efforts to save the wealthy, fashionable districts which were now being approached by the flames, such as the shopping mall the Royal Exchange and the opulent shops in Cheapside. John Evelyn wrote:

the conflagration was so universal, and the people so astonished, that from the beginning, I know not by what despondency or fate, they hardly stirred to quench it, so that there was nothing heard or seen but crying out and lamentation, running about like distracted creatures without at all attempting to save even their goods, such a strange consternation there was upon them.[31]

Large-scale looting had begun. The courtier Windham Sandys decribed behaviours as determined by social class: "For the first rank, they minded only for their own preservation; the middle sort [were] so distracted and amazed that they did not know what they did; the poorer, they minded nothing but pilfering."[32] By mid afternoon, many were fleeing to the open fields outside the City, such as Moorfields.[33] (Interesting description of location and character of Moorfields in Tinniswood, 104, with quotes from Evelyn and Pepys, though unfortunately from observations on the Wednesday. But Robinson does speak of flight to Moorfields on the Monday. Open civic park lined with brothels. Colourful.)

Among the shocked, homeless crowds, suspicion soon arose that the fire was no accident. The wind carried sparks and burning flakes long distances to lodge on thatched roofs and in wooden gutters, causing seemingly unrelated house fires to break out far from their source and giving rise to rumours that fresh fires were being set on purpose. Foreigners were immediately suspect, with the ongoing Second Anglo-Dutch War amplifying the rampant xenophobia that the English were already known for.[34] As fear and suspicion hardened into certainty on the Monday, reports circulated of imminent invasion, and of foreign undercover agents seen casting "fireballs" into houses. There were "a hundred stories," reports a contemporary observer, of foreigners caught with hand grenades, or trying to set fresh fires with matches,[35] Any tale against foreigners would be believed.[36] and there was a wave of street violence. William Taswell saw a mob loot the shop of a French painter and level it to the ground, and watched in horror as a blacksmith walked up to a Frenchman in the street and hit him over the head with an iron bar.[37] Many foreign nationals were arrested, one of the first being a Dutch baker with a shop in Westminster who was accused of trying to set fire to his own premises.[38]

London's local militia, known as the Trained Bands, were summoned and assembled for the emergency, but their efforts were increasingly and uselessly diverted from firefighting to the hunting down of suspicious characters. As suspicion rose to panic and collective paranoia on the Monday, the Trained Bands focused more and more on rounding up of foreigners, Catholics, and odd-looking people, and less on containing the conflagration.

This happened nationwide. Any good place to put those stories?

Tuesday, September 4[edit]

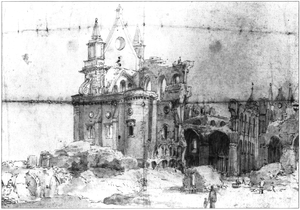

Robinson: "The [Tuesday] saw the greatest destruction. Both the King and the Duke of York were immersed in the battle against the fire, which was contained until late afternoon, when it jumped over the break at Mercers' Hall and began to consume Cheapside, London's widest and wealthiest street. While Pepys was busy evacuating his house - digging a pit in which he buried 'a parmazan cheese as well as my wine and some other things' - he had an inspiration. 'Blowing up houses... stopped the fire when it was done, bringing down the houses in the same places they stood, and then it was easy to quench what little fire was in it'. [This shows Robinson up. Blowing up houses with gunpowder was an old technique, not an "inspiration" of Pepys'.] Although demolition began to take effect in the east, in the west the fire had destroyed Newgate and Ludgate prisons, and was travelling along Fleet Street towards Chancery Lane. It was visible as far away as Enfield, embers were falling on Kensington, and flames surrounded St Paul's Cathedral, covered in scaffolding. This caught fire, soon followed by the timber roof beams. The lead roof melted and flowed down Ludgate Hill, and stones exploded from the building. Within a few hours the Cathedral was a ruin."[39]

Wednesday, September 5[edit]

Eye-witness accounts[edit]

The personal experiences of many Londoners during the fire are glimpsed in letters and memoirs. The two most famous diarists of the Restoration, Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn, recorded the events and their own reactions day by day, and made great efforts to keep themselves informed of what was happening all over the city and beyond it. For example, they both travelled out to the park area Moorfields north of the City on the Wednesday–the fourth day–to view the mighty encampment of distressed refugees there, which shocked them. Their diaries are the most important sources for all modern retellings of the day-by-day unfolding of the disaster. Both the most recent books on the fire, by Tinniswood (2003) and Hanson (2001), also rely on the brief memoirs of William Taswell, in 1666 a fourteen-year-old schoolboy at Westminster School.

- Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys (1633–1703), later M.P. for Harwich, was at the time of the fire a rising naval administrator. He influenced the direction of events of the first day, Sunday, September 2, by alerting the King to the alarming conflagration and then carrying the King's orders back to the Lord Mayor. Pepys is known for the restless curiosity and energy animating his famous diary, and even as he struggled to evacuate his belongings from his house and his papers from the Navy Office, both situated in Seething Lane in the City, he took pains to see as much as possible of the historic disaster taking place around him. On the Sunday morning, he climbed the Tower of London to get an overview, then went down to Pudding Lane by boat to get a closer look, then upriver to Whitehall to seek audience with the King, and in the early evening, with his wife and some friends, he again went on the river "and to the fire up and down, it still encreasing." They ordered the boatman to go "so near the fire as we could for smoke; and all over the Thames, with one's face in the wind, you were almost burned with a shower of firedrops." When the "firedrops" became unbearable, the party went on to an alehouse on the south bank and stayed there till darkness came and they could see the fire on London Bridge and across the river, "as only one entire arch of fire from this to the other side of the bridge, and in a bow up the hill for an arch of above a mile long: it made me weep to see it."

Pepys' words about "one entire arch of fire from this to the other side of the bridge" was apparently the exaggeration of shock, or an effect of the perspective from which he was seeing the bridge, as the fire in fact never got further than one third of the way south across the bridge. It was stopped by an open space between two groups of buildings on the bridge, the very same gap that had saved Bankside and Southwark in the fire of 1632 and confined the destruction to the City of London on the north bank. Now the same gap did so again.[40] At four on Monday morning, Pepys began to move his belongings out of the burning city, "and, Lord! to see how the streets and the highways are crowded with people running and riding, and getting of carts at any rate to fetch away things." He spent the Monday and Tuesday rescuing the Naval Board papers and burying them in a friends garden, liaising with suburban friends for the placement of his valuables and "best things", and assisting many distressed neighbours and acquaintances. In the small hours of Wednesday morning, he expected the approaching fire to torch his house and his office at any moment, and hastily sent the last of his valuables away by boat; however, both buildings survived, as the decisive creation of firebreaks by blowing up houses with gunpowder finally began to take effect. After four days of hardly any food or sleep, Pepys walked all over the smouldering city on the Wednesday, getting his feet hot, and climbed the steeple of Barking Church, from where he viewed "the saddest sight of desolation that I ever saw". Out at Moorfields, an open park space immediately north of the City, he saw a great encampment of homeless refugees, "poor wretches carrying their good there, and every body keeping his goods together by themselves", and noted that the price of bread in the environs of the park had doubled.

Summing up on September 7, Pepys remarked that "people do all the world over cry out of the simplicity [=the stupidity] of my Lord Mayor in generall; and more particularly in this business of the fire, laying it all upon him."

- John Evelyn

John Evelyn ... WHAT? Diary not on the web! I don't believe it! Later, then. :-(

- Ha! Google book search throws up a full-view 19th century edition.

John Evelyn (1620–1706), a .... hmmmm..... anyway, another diarist, lived four miles outside the City, in Deptford and so did not see the early stages of the disaster. On the Monday he went by coach to Southwark to watch, as did many other upper-class people, at first hand the view that Pepys had seen the day before, of the burning City from across the river. The conflagration was much larger now: "the whole City in dreadful flames near the water-side; all the houses from the Bridge, all Thames-street, and upwards towards Cheapside, down to the Three Cranes, were now consumed."[41]

Aaahh, excellent extract of I think the whole of Evelyn's account of the fire: http://www.authorsden.com/visit/viewarticle.asp?AuthorID=21190&id=19655

- William Taswell

William Taswell (1651-82), later rector of Newington, Surrey, and rector of Bermondsey, was in September 1666 a fourteen-year-old schoolboy at Westminster School. He first heard of the fire while listening to a sermon in Westminster Abbey on Sunday morning. Becoming aware of people outside running about "in a seeming disquietude and consternation",[42] and picking up a shout that London was burning, he dashed outside and down to the river. There he saw "four boats crowded with objects of distress", refugees from the fire a mile upriver, "scarce under any covering except that of a blanket." William went to school as usual on Monday morning, only to find himself marched with the rest of the school into the heart of the city by the Dean of Westminster, John Dolben, who was determined to help the firefighting effort. The Westminster boys managed to save the large church St Dunstan in the East, a couple of hundred yards east of Pudding Lane, which was still on the boundary of the fire zone since the principal spread was westward. The boys returned to school after this triumph, and the church burned down the next day. Tinniswood, who retells this story, comments that such heroic efforts were bound to fail in the absence of an organized operation.[43] As scapegoat paranoia and fears of invasion rose in the threatened city, William was horrified at the mob violence that he saw in the streets against "suspicious" foreigners. Leaving school on Tuesday night, he stood on Westminster Stairs and watched for an hour as the flames crept round St. Paul's Cathedral, whose thick stone walls everybody had thought an absolute refuge, until he saw flames appear on the roof at eight o'clock. On the fifth day, when the City of London had been reduced to rubble and glowing embers, William made his way to the ruins of St. Paul's and observed its charnel-house horrors with childish curiosity, stuffing his pockets with lumps of bell metal as souvenirs and picking up a sword and helmet to play soldiers.

Deaths and destruction[edit]

Traditional estimate of fatalities--uh, POV to call it "stupid", I suppose. Hanson implies in passing that the number is unknown and probably large, 123

The material destruction has been computed at 13,200 houses, besides 87 parish churches, St. Paul's Cathedral, and nearly all the buildings of the City authorities; the monetary value of the loss, first estimated at £100,000,000 in the currency of the time, was later reduced to an uncertain £10,000,000.[44] John Evelyn believed that he saw as many as "200,000 people of all ranks and stations dispersed, and lying along their heaps of what they could save" in the fields towards Islington and Highgate.[45] Providing for the refugees and calming public hysteria about scapegoats were the first urgencies; only then could rebuilding be planned for.[46] The social and economic problems created by the disaster were overwhelming.

Evacuation and refugees[edit]

The war, scapegoats, public unrest, royal proclamations, measures taken by the City, the plight of the refugees. Flight from London strongly encouraged by Charles, who feared yet another London rebellion.

National impact[edit]

Nationwide xenophobia scare.

- Prices and supplies

- Profiteering

- Labour market

- The Fire Court

Notes[edit]

- ^ Hanson, 80.

- ^ Oxford Illustrated History of Britain, 293–4.

- ^ John Evelyn in 1659, quoted in Tinniswood, 3. Except where otherwise indicated, this section is based on Tinniswood, 1–11.

- ^ Tinniswood, 4.

- ^ 330 acres is the size of the area within the Roman wall according to standard reference works, see for instance Sheppard, 37.[1], although Tinniswood gives that area as a square mile (=667 acres).

- ^ Tinniswood, 4.

- ^ See Hanson, 85-88, for the Republican temper of London.

- ^ See Tinniswood, 53.

- ^ Hanson, 80.

- ^ Hanson, 78.

- ^ Hanson, 77-80.

- ^ Rege Sincera (pseudonym), Observations both Historical and Moral upon the Burning of London, September 1666, quoted by Hanson, 80.

- ^ Hanson, 80.

- ^ Letter from an unknown correspondent to Lord Conway, September 1666, quoted by Tinniswood, 45-46.

- ^ Hanson, 101.

- ^ Robinson, Bruce, "London's Burning: The Great Fire"

- ^ Gough MSS London14, the Bodleian Library, quoted by Hanson, 123.

- ^ Hanson, 82.

- ^ A firehook was a heavy pole perhaps 30 feet long with a strong hook and ring at one end, which would be attached to the roof trees of a threatened house and operated by means of ropes and pulleys to pull the building down. (Tinniswood, 49).

- ^ "Bludworth's failure of nerve was crucial" (Tinniswood, 52).

- ^ See Robinson, London:Brighter Lights, Bigger City" and Tinniswood, 48-49.

- ^ Compare Hanson, who claims they had wheels (76), and Tinniswood, who states they did not (50).

- ^ The fire engines, for which a patent had been granted in 1625, were single-acting force pumps worked by long handles at the front and back (Tinniswood, 50).

- ^ All dates are given according to the New Style.

- ^ Tinniswood 42–43.

- ^ All quotes from and details involving Samuel Pepys come from his diary.

- ^ Tinniswood, 53.

- ^ Gazette, September 3 1666.

- ^ See firestorm and Hanson, 102–105.

- ^ Tinniswood,

- ^ Evelyn, 10.

- ^ Letter to Lord Scudamore, quoted by Tinniswood, 64.

- ^ Robinson, "London's Burning".

- ^ Tinniswood, 58 ff.

- ^ Hanson, 139.

- ^ Reddaway, 22, 25.

- ^ Tinniswood, 59.

- ^ "The conjunction of Dutchmen and bakeries proved too much for his neighbors", comments Tinniswood (61).

- ^ [http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/civil_war_revolution/great_fire_03.shtml London's Burning"

- ^ Robinson, "London's Burning: The Great Fire".

- ^ Evelyn, 10.

- ^ Tinniswood, 51.

- ^ 71

- ^ Reddaway, 26

- ^ Reddaway, 26

- ^ Reddaway, 27.

References[edit]

- Bray, R. S. (1996). Armies of pestilence: The Impact of Disease on History. ISBN 076071908.

- Evelyn, John (1854). Diary and Correspondence of John Evelyn, F.R.S.''London:Hursst and Blackett.

- Hanson, Neil (2001). The Dreadful Judgement: The True Story of the Great Fire of London. New York: Doubleday.

- Pepys, Samuel (ed. Robert Latham and William Matthews, 1995). The Diary of Samuel Pepys. 11 volumes. London: Harper Collins. First published between 1970 and 1983, by Bell & Hyman, London. Quotations from and details involving Pepys are taken from this standard, and copyright, edition. All web versions of the diaries are based on public domain 19th-century editions and unfortunately contain many errors, as the shorthand in which Pepy's diaries were originally written was not accurately transcribed until the pioneering work of Latham and Matthews.

- Reddaway, T. F. (1940). The Rebuilding of London After the Great Fire. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Robinson, Bruce, "London: Brighter Lights, Bigger City" at the BBC British history site, accessed August 12, 2006.

- Robinson, Bruce, "London's Burning: The Great Fire" at the BBC British history site, accessed August 12, 2006.

- Sheppard, Francis (1998). London: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tinniswood, Adrian (2003). By Permission of Heaven: The Story of the Great Fire of London. London: Jonathan Cape.

External links[edit]

Updated link to ample BBC history site

Museum of London answers questions, a minor piece but gives a pretty good bird's-eye view of the refugee problem and the impact on the economy. And explodes some myths (the 1665 plague made no difference to the Fire, and I *think* the Fire made no difference to the subsequent lessening of the plague. It's a myth that 18th-c conditions were any more salubrious than 17-c ones.

Holding area[edit]

Museum of London timeline[edit]

Simple timeline from http://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/learning/features_facts/tudor_stuart_london_1.html :

Saturday 1 September 1666

- The city is experiencing the end of a hot summer.

- Water levels of the Thames and the city wells are very low.

Sunday 2 September 1666

- 1.30am: A fire starts amongst some wood in Thomas Faryner's bakehouse in Pudding Lane.

- Fanned by an east wind, the fire spreads and jumps all firebreaks.

- 7.00am: Samuel Pepys hears that 300 houses have already burnt down.

- By the afternoon the fire has destroyed the entire waterfront warehousing as far as present day Southwark Bridge. The fire also spreads north towards Cheapside. Londoners begin to flee the City.

Monday 3 September 1666

- The fire gains momentum. It spreads west towards the Fleet River and north beyond Cornhill and the Royal Exchange.

- By order of King Charles II, the Duke of York, the King's brother, is placed in control of the City and uses his guards to try to put out the fire by creating firebreaks.

Tuesday 4 September 1666

- Soldiers from Middlesex, Hertfordshire and Kent are ordered into the City to help fight the fire.

- St Paul's Cathedral burns down. 'The stones of St Pauls flew like grenados, and the lead melted down the streets in a stream ...' (John Evelyn).

- The Guildhall and Bridewell Prison are destroyed by fire.

- In the east of the City, gunpowder is used to make firebreaks and save the Tower of London.

- During the night the wind drops and fire-fighters begin to control the flames.

Wednesday 5 September 1666

- Pepys takes his family to Woolwich as the fire gets close to his home.

- Buildings on Fenchurch Street, Gracechurch Street and Lombard Street are burnt down.

Thursday 6 September 1666

- By morning the Great Fire of London is extinguished.

Friday 7 September 1666

- '... up by five o'clock, and blessed by God! Find all well...' (Samuel Pepys)

- The results of the Great Fire

The fire destroyed about four fifths of the City of London. Only a small area in the north-east survived. The damage included:

13,200 houses St Paul's Cathedral 87 parish churches 6 chapels Bridewell Prison Newgate Prison The Guildhall 3 City gates The Custom House 4 stone bridges Sessions House The Royal Exchange 52 livery company halls

The cost of the fire damage to buildings and their contents was about �10 million. London's yearly income at the time was about �12,000.

Interpretation Unit, Museum of London (ed. Jane Sarre) August 2002

End of Museum of London quote[edit]

What did that matter? Plague article: "Plague cases continued at a modest pace until September 1666." Hmm. I suspect it's being stretched to MAKE the Fire seem significant in ending it. The GREAT Plague was in the summer of '65, surely. This needs checking up. (I think you will find that all major European cities were never completely free of the plague, there were just less occurances and less epidemics at certain times - I've read that somewhere but can't remember where - a book about Venezia I think, I'll try and find it Giano | talk 21:51, 12 August 2006 (UTC))

- OK, darlin', see also the last external link.

- Trained Bands

Hanson, 137. Tinniswood, 105

Rebuilding[edit]

However, architecturally Inigo Jones had begun to introduce the palladianism inspired by the late Renaissance architecture of Italy, however these more classically inspired forms of architecture had been arrested by the overthrow of the monarchy. Changes had begun though immediately following the restoration, and Jones had added a classical portico the the front of St. Paul's cathedral.

Following the fire Christopher Wren was put in charge of re-building the city. His original plans involved rebuilding the city in brick and stone to a grid plan with continental piazzas and long straight avenues, from 1667, Parliament begain raising funds for an ambitious re-building scheme by taxing coal. However, the city was not rebuilt according to Wren's grandiose baroque scheme of a city of long straight streets and piazzas, this was largely due to delaying legal disputes over ownership of land, and the fact that owners of the destroyed shops and houses had to repay for their own rebuilding work. Finaly, subject to certain conditions owners were allowed to retain their former sites. This is the reason today's modern London has a medieval street layout - "Seen in isolation" writes Reddaway, Wren's draft "has bred the story of a great and neglected opportunity. The documents tell a different tale."[1]

Ethos of Wren's Churches[edit]

Wren newly appointed as Surveyor General began to supervise the construction of 57 new churches, much of the design work of which was delegated. The greater part of the cost of replacing the public buildings was met by the City and its companies. [2] Amongst the new designs were plans for the first new churches to have been built in England since the reformation.[3] Wren's new churches were revolutionary in English ecclesiastical architecture in that they ignored the traditional medieval cruciform plan, while externally they resembled the renaissance Roman Catholic churches of Europe internally the renaissance layout was adapted to suit the protestant liturgy. Which unlike that of the Roman Catholic church places greater emphasis on the sermon rather than the ritual taking place at the high altar, hence Wren's churches were basically halls, often with a gallery which allowed everyone to see and hear the preacher thus the chancel became vestigial.

Diverse[edit]

Hey, do you still have access to the DNB? I don't. If you'd like a little job, could you look up William Taswell for me? The 17th-century one. (I think there is a later William Taswell, just ignore him.) My WT wandered about in London and observed the horrors of the fire in 1666, as a 14-year-old schoolboy, and eventually wrote about it in his "autobiography", a short piece. What I'd like to know is when he wrote it down, if anybody knows--obviously, this is a very good source if he kept a journal, less good if he's just remembering/distorting his observations many years later. I like William, he seems like a good kid. He was horrified by the street violence against foreigners that he saw. Was he alone and at a loose end in London? Stuff like that. I know he had been sent home from his school because they had to close on account of the plague.

This is his autobiography: "Autobiography and Anecdotes by William Taswell D.D.", ed. G. P. Elliott, Camden Miscellany II (1853), 1-37. The next thing will perhaps be that one of those clever people who frequent your page (not much like the crowd on mine!) finds it on the web for me (the wandering glass says HINT HINT). Bishonen | talk 20:08, 15 August 2006 (UTC).

- All hits for "Taswell" in ODNB:

- "Tanswell [formerly Cock], John (1800–1864), lawyer and antiquary, was born at Bedford Square, London, on 3 September 1800, the sixth son of Stephen Cock and his wife, Ann Tanswell (or Taswell), a relative of the Revd William Taswell (d. 1731), rector of St Mary's, Newington, Surrey."

- In the article on Edward Lake (1641–1704), Church of England clergyman: "With his wife, Margaret (1638–1712), Lake had three daughters who survived him, Mary, Ann, and Frances, who married William Taswell DD on 21 May 1695 at St Mary-at-Hill. Taswell later published a collection of sixteen of Lake's sermons."

- "Langmead, Thomas Pitt Taswell- (1840–1882), legal writer, was the only son of Thomas Langmead, gentleman, of St Giles-in-the-Fields, London, and his wife, Elizabeth, daughter of Stephen Cock Taswell, a descendant of an old family formerly settled at Limington, Somerset. He assumed Taswell as an additional surname in 1864." (Seems to be the same family.)

- That's it. (And all three of these ODNB biographees are red links here.) up+l+and 06:34, 16 August 2006 (UTC)

- All hits for "Taswell" in ODNB:

- "Clever people" indeed. He scorched his schoolboy shoes on the hot ground near St Pauls, it would seem, 4 days after the fire started.[2] I have found a reference to "Volume LV Miscellany, Vol. II, Camden Society, 1853 - Autobiography and anecdotes, by William Taswell, D.D. sometime rector of Newington, Surrey, rector of Bermondsey, and previously student of Christ Church, Oxford, AD 1651-82, ed. George Percy Elliott"[3] (or you could buy a copy for £12) and someone of the same name was burgled in December 1716 [4] Another William Taswell was at Oxford in the 1570s (cited here) and there seems to an author of a recent history journal article, William Taswell, “Plague and the Fire,” History Today vol. 27 No. 12 (December 1977) pp 812-817 here. -- ALoan (Talk) 00:22, 16 August 2006 (UTC)

the conflagration was so universal, and the people so astonished, that from the beginning, I know not by what despondency or fate, they hardly stirred to quench it, so that there was nothing heard or seen but crying out and lamentation, running about like distracted creatures without at all attempting to save even their goods, such a strange consternation there was upon them; so as it burned both in breadth and length the churches, public halls, Exchange, hospitals, monuments and ornaments, leaping after a prodigious manner from house to house and street to street, at great distances from one from the other, for the heat with a long set of fair and warm weather had even ignited the air, and prepared the materials to conceive the fire, which devoured after an incredible manner, houses, furniture and everything.