User:Jaydavidmartin/Random

Revisions to Electoral Count Act[edit]

In response to attempts by Republican lawmakers to invalidate the election results of several swing states during the 2021 United States Electoral College vote count, national Democrats have proposed amending the Electoral Count Act.[1] Under the United State's Electoral College system, in early January after a presidential election Congress meets in a joint session overseen by the Vice President to tally the electoral votes of each state. During the vote count—which in most presidential elections is little more than a formality—the Electoral Count Act allows lawmakers to object to a state's vote count; the House and Senate then hold separate votes on whether to sustain the the objection. If a majority of both chambers vote to sustain the objection, that state's electoral votes are rejected.

After the 2020 presidential election, allies of President Donald Trump sought to utilize this provision of the Electoral Count Act to reject the certified electoral votes of enough swing states that had gone to Democratic challenger Joe Biden to swing the election to Donald Trump, who had lost the election. As outlined in the Eastman memorandums, Trump's team first sought to persuade then-Vice President Mike Pence to unilaterally throw out the certified results of seven states whose votes had gone to Joe Biden.[2] to swing The proposal has at least some bipartisan support, with a number of state and local lawmakers from both parties, several conservative and bipartisan groups, and Republican Liz Cheney (who has been ostracized by most members of her party) backing reform.[1]

Racial discrimination[edit]

Human rights organizations, civil rights groups, academics, journalists, and other critics have argued that the US justice system exhibits racial biases that harm minority groups, particularly African Americans.[3][4] There are significant racial disparities among the United States prison population, with black individuals making up 38.2% of the federal prison population despite accounting for only 13.4% of the total population.[5][6] Studies have also found that black people, as well as other minority groups, are shot and killed by the police at higher rates than white people,[7][8] tend to receive harsher punishments than white people,[9] are more likely to be charged for drug crimes despite consuming drugs at similar rates as white people,[10][11] are (along with Native American/Alaska Native men and women, and Latino men) at higher lifetime risk of being killed by police than white people,[12] are more likely to be stopped by police while driving,[13] and are more likely to be arrested during a police stop.[14] As the Sentencing Project said in their report to the United Nations:[15]

African Americans are more likely than white Americans to be arrested; once arrested, they are more likely to be convicted; and once convicted, and they are more likely to experience lengthy prison sentences.

The cause of this are disputed. There is a widespread belief among the American public that racial discrimination by the police is a persistent problem,[16] and many academics and journalists assert that systemic racism, as well as a number of factors like concentrated poverty and higher rates of substandard housing (which has also lead to greater rates of lead poisoning among African Americans) that they argue arise out of past racial segregation or other form of historical oppression,[17] contribute to the racial disparities.[18][19][20] Some—particularly conservative political commentators—however, allege that the disparities arise primarily out of greater rates of criminal activity among black people,[21][22][23] and point to studies that have found little evidence that anti-black racism causes disparities in altercations with the police.[24]

Background (Constitution of South Korea)[edit]

Japanese colonial rule[edit]

Independence movement[edit]

History (Constitution of South Korea)[edit]

Be sure to move History section here, in between Background and Preamble

Preamble (Constitution of South Korea)[edit]

Succession of spirit[edit]

The preamble states that the values and ideals of the constitution are directly influenced by several historical events. In particular, it asserts that the constitution was established in the spirit of "upholding the cause of the Provisional Republic of Korea Government (the Korean government exiled after the imposition of Japanese colonial rule of Korea), born of the March First Independence Movement of 1919 and the democratic ideals of the April Nineteenth Uprising of 1960 against injustice".[25]

The Provisional Charter of Korea[edit]

The Provisional Charter of Korea, the founding document of the provisional government, serves as the basis for the current constitution.[26] Promulgated in 1919, the charter first gave the ‘Republic of Korea’ it name and laid out the ideas forming the backbone of later South Korean constitutions.

These ten articles are:[27]

- The Republic of Korea is a democratic republic country.

- The Republic of Korea should be governed by the provisional people of the provisional government.

- All citizens of the Republic of Korea are equal without gender, wealth and stratum.

- All citizens of the Republic of Korea have the rights to be free of religion, media, writing, publishing, association, assembly, the charge of address, body and ownership.

- The citizens who have the qualification of the citizen of the Republic of Korea have a right to vote and to be elected.

- The citizens of the Republic of Korea have a duty to education, taxation, and military service.

- The Republic of Korea will join the League of Nations in order to exert its founding spirit in the world and to contribute to human culture and peace by the will of the citizens.

- The Republic of Korea gives preference to the old imperial family.

- The Republic of Korea forbids the punishment of life, body, and licensed prostitution.

- The Provisional Government convenes the National Assembly within one year after the restoration of the country.

March 1st Movement[edit]

April Revolution[edit]

Quantum computing[edit]

Alternative representations[edit]

While the quantum circuit model of computation described above is the prevailing mathematical representation of quantum computation, there exist other, equivalent representations—just as there exist multiple equivalent mathematical representations for classical computation.[28]

Quantum Turing machine[edit]

While the standard treatment of quantum computation is the quantum circuit model, the corresponding classical circuit model is not the standard treatment of classical computation. Rather, the theory of classical computation is generally introduced with the computationally equivalent(source) Turing machine. Quantum computation can similarly be represented using the quantum Turing machine.

Topological quantum computer[edit]

Adiabatic quantum computation[edit]

Quantum complexity theory[edit]

BQP[edit]

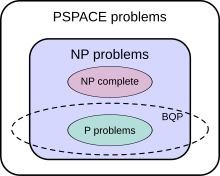

The class of problems that can be efficiently solved by a quantum computer with bounded error is called BQP, for "bounded error, quantum, polynomial time". Quantum computers only run probabilistic algorithms, so a quantum computer is said to "solve" a problem if, for every instance, its answer will be right with high probability. As a class of probabilistic problems, BQP is the quantum counterpart to BPP ("bounded error, probabilistic, polynomial time"), the class of problems that can be efficiently solved by probabilistic classical computers with bounded error.[30] It is known that BPPBQP and widely suspected, but not proven, that BQPBPP, which intuitively would mean that quantum computers are more powerful than classical computers in terms of time complexity.[31]

The exact relationship of BQP to P, NP, and PSPACE is not known. However, it is known that PBQPPSPACE; that is, the class of problems that can be efficiently solved by quantum computers includes all problems that can be efficiently solved by deterministic classical computers but does not include any problems that cannot be solved by classical computers with polynomial space resources. It is further suspected that BQP is a strict superset of P, meaning there are problems that are efficiently solvable by quantum computers that are not efficiently solvable by deterministic classical computers. For instance, integer factorization and the discrete logarithm problem are NP problems in BQP that are suspected to be outside of P. On the relationship of BQP to NP, little is known. However, it is suspected that BQP does not contain NP; that is, it is believed that there are efficiently checkable problems that are not efficiently solvable by a quantum computer. Consequently, it is also suspected that BQP is disjoint from the class of NP-complete problems.[32]

QMA[edit]

Resources[edit]

Examples[edit]

Integers and modular addition[edit]

The set of integers Z, with the operation of addition, forms a group.[33] It is an infinite cyclic group because all integers can be written by repeatedly adding or subtracting the single number 1, i.e. Z = ⟨1⟩. In this group, 1 and −1 are the only generators. Every element in Z has infinite order. Every infinite cyclic group is isomorphic to Z.

Multiplicative group of integers modulo n[edit]

Symmetric group[edit]

The symmetric group S3 has the following multiplication table.

• e s t u v w e e s t u v w s s e v w t u t t u e s w v u u t w v e s v v w s e u t w w v u t s e

This group has six elements, so ord(S3) = 6. By definition, the order of the identity, e, is one, since e1 = e. Each of s, t, and w squares to e, so these group elements have order two: |s| = |t| = |w| = 2. Finally, u and v have order 3, since u3 = vu = e, and v3 = uv = e.

Chinese constitution[edit]

The Constitution of the People's Republic of China is nominally the supreme law of the People's Republic of China. It was adopted by the 5th National People's Congress on December 4, 1982, and has been amended 5 times: in 1988, 1993, 1999, 2004 and 2018. It is the fourth constitution in the country's history, superseding the 1954 constitution, the 1975 constitution, and the 1978 constitution.

Though technically the "supreme legal authority" and "fundamental law of the state", the ruling Chinese Communist Party has a documented history of violating many of the constitution's provisions and censoring calls for greater adherence to it.[1][2][3] According to the constitution, all national legislative power is vested in the hands of the National People’s Congress and its Standing Committee; however, actual decision-making power resides with the Communist Party of China.[34] Furthermore, claims of violations of constitutional rights are rarely used in Chinese courts, and the National People's Congress Constitution and Law Committee, the legislative committee responsible for constitutional review, has never ruled a law or regulation unconstitutional.[4][5]

1982 Constitution[edit]

The 1982 Constitution reflects Deng Xiaoping's determination to lay a lasting institutional foundation for domestic stability and modernization. The new State Constitution provides a legal basis for the broad changes in China's social and economic institutions and significantly revises government structure. The posts of President and Vice President (which were abolished in the 1975 and 1978 constitutions) are re-established in the 1982 Constitution.

There have been five major revisions by the National People's Congress (NPC) to the 1982 Constitution.

Much of the PRC Constitution is modelled after the 1936 Constitution of the Soviet Union, but there are some significant differences. For example, while the Soviet constitution contains an explicit right of secession, the Chinese constitution explicitly forbids secession. While the Soviet constitution formally creates a federal system, the Chinese constitution formally creates a unitary multi-national state.

The 1982 State Constitution is a lengthy, hybrid document with 138 articles.[35] Large sections were adapted directly from the 1978 constitution, but many of its changes derive from the 1954 constitution. Specifically, the new Constitution de-emphasizes class struggle and places top priority on development and on incorporating the contributions and interests of non-party groups that can play a central role in modernization.

Article 1 of the State Constitution describes China as "a socialist state under the people's democratic dictatorship"[36] meaning that the system is based on an alliance of the working classes—in communist terminology, the workers and peasants—and is led by the Communist Party, the vanguard of the working class. Elsewhere, the Constitution provides for a renewed and vital role for the groups that make up that basic alliance—the CPPCC, democratic parties, and mass organizations.

The 1982 Constitution expunges almost all of the rhetoric associated with the Cultural Revolution incorporated in the 1978 version. In fact, the Constitution omits all references to the Cultural Revolution and restates Chairman Mao Zedong's contributions in accordance with a major historical reassessment produced in June 1981 at the Sixth Plenum of the Eleventh Central Committee, the "Resolution on Some Historical Issues of the Party since the Founding of the People's Republic." [37]

Emphasis is also placed throughout the 1982 State Constitution on socialist law as a regulator of political behaviour. Unlike the 1977 Soviet Constitution, the text of the Constitution itself doesn't explicitly mention the Communist Party of China and there is an explicit statement in Article 5 that the Constitution and law are supreme over all organizations and individuals.

Thus, the rights and obligations of citizens are set out in detail far exceeding that provided in the 1978 constitution. Probably because of the excesses that filled the years of the Cultural Revolution, the 1982 Constitution gives even greater attention to clarifying citizens' "fundamental rights and duties" than the 1954 constitution did, like the right to vote and to run for election begins at the age of eighteen except for those disenfranchised by law. The Constitution also guarantees the freedom of religious worship as well as the "freedom not to believe in any religion" and affirms that "religious bodies and religious affairs are not subject to any foreign domination."

Article 35 of the 1982 State Constitution proclaims that "citizens of the People's Republic of China enjoy freedom of speech, of the press, of assembly, of association, of procession, and of demonstration."[36] In the 1978 constitution, these rights were guaranteed, but so were the right to strike and the "four big rights", often called the "four bigs": to speak out freely, air views fully, hold great debates, and write big-character posters. In February 1980, following the Democracy Wall period, the four bigs were abolished in response to a party decision ratified by the National People's Congress. The right to strike was also dropped from the 1982 Constitution. The widespread expression of the four big rights during the student protests of late 1986 elicited the regime's strong censure because of their illegality. The official response cited Article 53 of the 1982 Constitution, which states that citizens must abide by the law and observe labor discipline and public order. Besides being illegal, practising the four big rights offered the possibility of straying into criticism of the Communist Party of China, which was in fact what appeared in student wall posters. In a new era that strove for political stability and economic development, party leaders considered the four big rights politically destabilizing. Chinese citizens are prohibited from forming new political parties.[38]

Among the political rights granted by the constitution, all Chinese citizens have rights to elect and be elected.[39] According to the later promulgated election law, rural residents had only 1/4 vote power of townsmen (formerly 1/8). As Chinese citizens are categorized into rural resident and town resident, and the constitution has no stipulation of freedom of transference, those rural residents are restricted by the Hukou (registered permanent residence) and have fewer political, economic, and educational rights. This problem has largely been addressed with various and ongoing reforms of Hukou in 2007.[citation needed] The fore-said ratio of vote power has been readjusted to 1:1 by an amendment to the election law passed in March 2010.[40]

The 1982 State Constitution is also more specific about the responsibilities and functions of offices and organs in the state structure. There are clear admonitions against familiar Chinese practices that the reformers have labelled abuses, such as concentrating power in the hands of a few leaders and permitting lifelong tenure in leadership positions. On the other hand, the constitution strongly oppose the western system of separation of powers by executive, legislature and judicial. It stipulates the NPC as the highest organ of state authority power, under which the State Council, the Supreme People's Court, and the Supreme People's Procuratorate shall be elected and responsible for the NPC.

In addition, the 1982 Constitution provides an extensive legal framework for the liberalizing economic policies of the 1980s. It allows the collective economic sector not owned by the state a broader role and provides for limited private economic activity. Members of the expanded rural collectives have the right "to farm private plots, engage in household sideline production, and raise privately owned livestock." The primary emphasis is given to expanding the national economy, which is to be accomplished by balancing centralized economic planning with supplementary regulation by the market.

Another key difference between the 1978 and 1982 state constitutions is the latter's approach to outside help for the modernization program. Whereas the 1978 constitution stressed "self-reliance" in modernization efforts, the 1982 document provides the constitutional basis for the considerable body of laws passed by the NPC in subsequent years permitting and encouraging extensive foreign participation in all aspects of the economy. In addition, the 1982 document reflects the more flexible and less ideological orientation of foreign policy since 1978. Such phrases as "proletarian internationalism" and "social imperialism" have been dropped.

- ^ a b Broadwater, Luke; Corasaniti, Nick (December 4, 2021). "Fearing a Repeat of Jan. 6, Congress Eyes Changes to Electoral Count Law". The New York Times.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Gangel, Jamie; Herb, Jeremy (September 21, 2021). "Memo shows Trump lawyer's six-step plan for Pence to overturn the election". CNN.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Balko, Radley (10 June 2020). "There's overwhelming evidence that the criminal justice system is racist. Here's the proof". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 12 July 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ "Criminal Justice Fact Sheet". National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Archived from the original on 12 July 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ "Inmate Race". Federal Bureau of Prisons. 4 July 2020. Archived from the original on 6 July 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ "Quick Facts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 13 July 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ "Fatal Force". The Washington Post. 13 July 2020. Archived from the original on 13 July 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ "The Counted: People killed by police in the US". The Guardian. 2016. Archived from the original on 10 July 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ "Demographic Differences in Sentencing". United States Sentencing Commission. United States Federal Judiciary. Archived from the original on 7 July 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

[T]he commission found: 1. Black male offenders continued to receive longer sentences than similarly situated White male offenders.

- ^ "Decades of Disparity: Drug Arrests and Race in the United States". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 7 July 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ "Rates of Drug Use and Sales, by Race; Rates of Drug Related Criminal Justice Measures, by Race". The Hamilton Project. The Brookings Institution. 21 October 2016. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Edwards, Frank (3 July 2019). "Risk of being killed by police use of force in the United States by age, race–ethnicity, and sex". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Archived from the original on 14 July 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ "Findings". Stanford Open Policing Project. Archived from the original on 13 July 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

The data show that officers generally stop black drivers at higher rates than white drivers, and stop Hispanic drivers at similar or lower rates than white drivers.

- ^ Kochel, Tammy Rhineheart; Wilson, David B.; Mastrofski, Steven D. (25 May 2011). "Effects of Suspect Race on Officers' Arrest Decisions". Criminology. 49 (2): 473–512 – via Wiley Online Library.

- ^ "Report to the United Nations on Racial Disparities in the U.S. Criminal Justice System". The Sentencing Project. 19 April 2018. Archived from the original on 30 June 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Best, Ryan; Rogers, Kaleigh (10 June 2020). "Do You Know How Divided White And Black Americans Are On Racism?". FiveThirtyEight. Archived from the original on 5 July 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

[A] majority of black and white respondents agree that police don't treat black and white people equally.

- ^ "How black lives can get better: Segregation still blights the lives of African-Americans". The Economist. 9 July 2020. Archived from the original on 13 July 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Collins, Sean (17 June 2020). "The systemic racism black Americans face, explained in 9 charts". Vox. Archived from the original on 12 July 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Pierson, Emma (20 June 2020). "Barr says there's no systemic racism in policing. Our data says the attorney general is wrong". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 12 July 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Lopez, German (15 August 2016). "How systemic racism entangles all police officers — even black cops". Vox. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Cesario, Joseph; Johnson, David (23 July 2019). "Our Database of Police Officers in Fatal Shootings Reveals Who Shot Citizens". Foundation for Economic Research. Archived from the original on 6 July 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Mac Donald, Heather (2 June 2020). "The Myth of Systemic Police Racism". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 13 July 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Lowry, Rich (7 August 2018). "Elizabeth Warren's Lie". National Review. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

The biggest reason for the overall disparity in incarceration is different rates of offending.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Officer characteristics and racial disparities in fatal officer-involved shootings". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Archived from the original on 29 June 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ "Korea (Republic of)'s Constitution of 1948 with Amendments through 1987" (PDF). Constitute Project.

- ^ Reexamining Political Participation in Rousseau’s Political Thought: Does Citizens’Political Participation Include Public Discussions and Debates edited by KANG Jung In

- ^ 한국근현대사사전. 가람기획: 한국사사전편찬회. 2005. ISBN 978-8984351936.

- ^ Nielsen, Chuang p. 203

- ^ Nielsen, p. 42

- ^ Nielsen, p. 41

- ^ Nielsen, p. 201

- ^ Bernstein, Ethan; Vazirani, Umesh (1997). "Quantum Complexity Theory". SIAM Journal on Computing. 26 (5): 1411–1473. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.144.7852. doi:10.1137/S0097539796300921.

- ^ "Cyclic group", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- ^ "China". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ "China 1982 (rev. 2004)". Constitute. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- ^ a b "CONSTITUTION OF THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA". People's Daily. December 4, 1982.

- ^ "Resolution on certain questions..." marxists.org.

- ^ Worden, Robert L.; Savada, Andrea Matles; Dolan, Ronald E., eds. (1987). "The Government". China: A Country Study. Washington DC: Government Printing Office.

- ^ "China 1982 (rev. 2004)". Constitute. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- ^ "城乡居民选举首次实现同票同权(Chinese)". Archived from the original on July 17, 2015. Retrieved July 17, 2015.