User:Jengy94/Chinese nationalism

Ideological sources of Chinese nationalism[edit]

The discussion of modern Chinese nationalism has dominated many political and intellectual debates since the late nineteenth century. Political scientist Suisheng Zhao argues that nationalism in China is not monolithic but exists in various forms, including political, liberal, ethnical, and state nationalism.[1] Over the first half of the twentieth century, Chinese nationalism has constituted a crucial part of many political ideologies, including the anti-Manchuism during the 1911 Revolution, the anti-imperialist sentiment of the May Fourth Movement in 1919, and the Maoist thoughts that guided the Communist Revolution in 1949. The origin of modern Chinese nationalism can be traced back to the intellectual debate on race and nation in late nineteenth century. Shaped by the global discourse of social Darwinism, reformers and intellectuals debated how to build a new Chinese national subject based on a proper racial order, particularly the Man-Han relations.[2] After the collapse of the Qing regime and the founding of the Republic of China in 1911, concerns of both domestic and international threat made the role of racism decline, while anti-imperialism became the new dominant ideology of Chinese nationalism over the 1910s. While intellectuals and elites advocated their distinctive thoughts on Chinese nationalism, political scientist Chalmers Johnson has pointed out that most of these ideas had very little to do with China's majority population -- the Chinese peasantry. He thus proposes to supplement the Chinese communist ideology in the discussion of Chinese nationalism, which he labels "peasant nationalism."[3]

Chinese nationalism in the early twentieth century was primarily based on anti-Manchurism, an ideology that was prevalent among Chinese revolutionaries from late nineteenth century to the turn of the twentieth century. After Qing's defeat in the Sino-Japanese War of 1895, reformers and intellectuals debated how to strengthen the nation, the discussion of which centered on the issue of race. Liang Qichao, a late Qing reformist who participated in the Hundred Days' Reform of 1898, contended that the boundary between Han and Man must be erased (ping Man-Han zhi jie).[4] Liang's thought was based on the idea of racial competition, a concept originating from social Darwinism that believed only superior races would survive whereas the inferior races were bound to extinct. Liang attributed the decline of China to the Manchu (Qing) rulers, who treated the Han as an "alien race" and imposed a racial hierarchy between the Han and the Manchus while ignoring the threat of imperial powers.[5] Liang's critique of the Qing court and the Man-Han relations laid the foundation for anti-Manchuism, an ideology that early Republican revolutionaries advocated in their efforts to overthrow the Qing dynasty and found a new Republic. In his writing “Revolutionary Army,” Zou Rong, an active Chinese revolutionary at the turn of the twentieth century, demanded a revolution education for the Han people who were suffering from the oppression of the Manchu rule.[6] He argued that China should be a nation of the orthodox Han Chinese and no alien race shall rule over them. According to Zou, the Han Chinese, as the decedents of the Yellow Emperor, must overthrow the Manchu rule to restore their legitimacy and rights. Wang Jingwei, a Chinese revolutionary who later became an important figure of the Guomindang, also believed that the Manchus were an inferior race. Wang contended that a state consisting of a single race would be superior to those multiracial ones. Most of the Republican revolutionaries agreed that preserving the race was vital to the survival of the nation. Since the Han had asserted its dominant role in Chinese nationalism, the Manchus had to be either absorbed or eradicated.[7] Historian Prasenjit Duara summarized this by stating that the Republican revolutionaries primarily drew on the international discourse of "racist evolutionism" to envision a "racially purified China."[7]

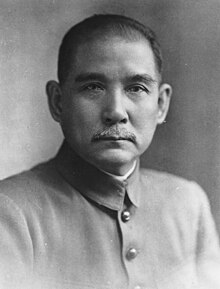

After the 1911 Revolution, Sun Yat-sen established the Republic of China, the national flag of which contained five colors with each symbolizing a major racial ethnicity of China. This marked a shift from the earlier discourse of radical racism and assimilation of the non-Han groups to the political autonomy of the five races.[8] The rhetorical move, as China historian Joseph Esherick points out, was based on the practical concerns of both imperial threats from the international environment and conflicts on the Chinese frontiers.[9] While both Japan and Russia were encroaching China, the newly born republic also faced ethnic movements in Mongolia and Tibet which claimed themselves to be part of the Qing Empire rather than the Republic of China. Pressured by both domestic and international problems, the fragile Republican regime decided to maintain the borders of the Qing Empire to keep its territories intact.[9] With the increasing threat from the imperialist powers in the 1910s, anti-imperialist sentiments started to grow and spread in China. An ideal of "a morally just universe," anti-imperialism made racism appear shameful and thus took over its dominant role in the conceptualization of Chinese nationalism.[10] Yet racism never perished. Instead, it was embedded by other social realms, including the discourse of eugenics and racial hygiene.[11]

In addition to anti-Manchurism and anti-imperialism, political scientist Chalmers Johnson has argued that the rise to power of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) through its alliance with the peasantry should also be understood as "a species of nationalism."[12] Johnson observes that social mobilization, a force that unites people to form a political community together, is the "primary tool" for conceptualizing nationalism.[13] In the context of social mobilization, Chinese nationalism only fully emerged during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), when the CCP mobilized the peasantry to fight against the Japanese invaders. Johnson contends that early nationalism of the Guomindang was quite similar to the late nineteenth-century nationalism in Europe, as both referred to the search for their national identities and positions in the modern world by the intelligentsia.[14] He argues that nationalism constructed by the intellectuals is not identical to nationalism based on mass mobilization, as the nationalist movements led by the Guomindang, as well as the May Fourth Movement in 1919, were not mass movements because their participants were only a small proportion of the society where the peasants were simply absent. When the Second Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937, the CCP began to mobilize the Chinese peasantry through mass propaganda of national salvation (jiuguo). Johnson observed that the primary shift of the CCP's post-1937 propaganda was its focus on the discourse of national salvation and the temporary retreat of its Communist agenda on class struggle and land redistribution.[15] The wartime alliance of the Chinese peasantry and the CCP manifests how the nationalist ideology of the CCP, or the peasant nationalism, reinforced the desire of the Chinese to save and build a strong nation.[16]

- ^ Zhao, Suisheng, 1954- (2004). A nation-state by construction : dynamics of modern Chinese nationalism. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4897-7. OCLC 54694622.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Duara, Prasenjit (1995). Rescuing History from the Nation. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-16722-0.

- ^ Johnson, Chalmers, 1931-2010. (1962). Peasant nationalism and communist power; the emergence of revolutionary China 1937-1945. Stanford, Calif.,: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0074-0. OCLC 825900.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Rhoads, Edward J. M. (2000). Manchus & Han : ethnic relations and political power in late Qing and early republican China, 1861-1928. Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-295-80412-5. OCLC 774282702.

- ^ Rhoads, Edward J. M. (2000). Manchus & Han : ethnic relations and political power in late Qing and early republican China, 1861-1928. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-98040-9. OCLC 1120670985.

- ^ Zou, Rong (1903). "The Revolutionary Army". Contemporary Chinese Thought. 31: 32–38.

- ^ a b Duara, Prasenjit (1995). Rescuing History from the Nation. University of Chicago Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-226-16722-0.

- ^ Duara, Prasenjit (1995). Rescuing History from the Nation. University of Chicago Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-226-16722-0.

- ^ a b Esherick, Joseph, MitwirkendeR. Kayalı, Hasan, MitwirkendeR. Van Young, Eric, MitwirkendeR. (2011). Empire to nation : historical perspectives on the making of the modern world. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-7815-9. OCLC 1030355615.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Duara, Prasenjit (1995). Rescuing History from the Nation. University of Chicago Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-226-16722-0.

- ^ Dikötter, Frank. (1998). Imperfect conceptions : medical knowledge, birth defects, and eugenics in China. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11370-6. OCLC 38909337.

- ^ Johnson, Chalmers, 1931-2010. (1962). Peasant nationalism and communist power; the emergence of revolutionary China 1937-1945. Stanford, Calif.,: Stanford University Press. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-0-8047-0074-0. OCLC 825900.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Johnson, Chalmers, 1931-2010. (1962). Peasant nationalism and communist power; the emergence of revolutionary China 1937-1945. Stanford, Calif.,: Stanford University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-8047-0074-0. OCLC 825900.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Johnson, Chalmers, 1931-2010. (1962). Peasant nationalism and communist power; the emergence of revolutionary China 1937-1945. Stanford, Calif.,: Stanford University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8047-0074-0. OCLC 825900.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Johnson, Chalmers, 1931-2010. (1962). Peasant nationalism and communist power; the emergence of revolutionary China 1937-1945. Stanford, Calif.,: Stanford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-8047-0074-0. OCLC 825900.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Johnson, Chalmers, 1931-2010. (1962). Peasant nationalism and communist power; the emergence of revolutionary China 1937-1945. Stanford, Calif.,: Stanford University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-8047-0074-0. OCLC 825900.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)