User:Jonah Kutell/sandbox

Mandalas in Science and Medicine[edit]

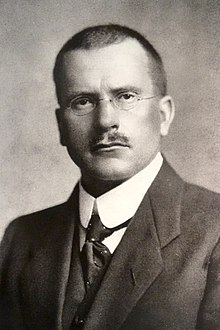

Mandalas have appeared in science and medicine, reappearing over and over from being devices utilized and studied in therapy, to being visualized in cell biology to and being recognized as a metaphor which represents human thought.[2]Sanskrit for circle, these circular apparitions have made their way into many cultures ranging from the Celtics in their creation of Celtic crosses and other geometric patterns, over to Asian countries dating back as far as Mesopotamian art.[3]Carl Gustav Jung, a swiss Psychiatrist held a deep fascination with Mandalas and focused a large amount of his thought and research toward their meaning and implication, due to this, mandalas have been developed and idealized as having stress reducing properties in their creation and viewing along with other implications which relate to their affect on the mind.[3]

History of Mandalas[edit]

A mandala is a typically circular, geometric art diagram which contain patterns that are typically held in a uniform, symmetric form.[5] The representations vary depending on the artist but common representations include but are not limited to, wholeness, unity, the circle of life and death, and the disorder of the universe.[5] These art forms originated in Buddhist and Hindi artwork dating to the first century BCE and spread it's way across Asia through the silk road.[5] Mandala artwork is plentiful in eastern Asia and can vary from region to region as much as it may vary from artist to artist. The Sand mandala is an example of this variation and refers to the ritual creation and destruction of these pieces by the Tibetan monks who create them, thus, in the ritual creation and destruction of these pieces, the artists themselves may be an advocate of order in the universe.[6]Order is a central theme in most mandalas, but specifically the order of ones self is reflected within the art.[3]Hinduism is referred to as eternal order where this order was created from an all powerful being far too complex to understand, so to understand this, during the ancient Vedic period, a series of holy scriptures were created called the Rigveda which chronicled much of the religious observations through the ten books which were apart of it, placing context among the order of the universe.[3]These books were referred to as mandalas as it moves from disorder and lack of understanding toward a center of order and meaning, the images which correspond and were created to follow the text are the oldest mandalas that have been discovered.[3] Mandalas in Buddhism are significant as well and were seen after the early days upon it's development as Siddhartha Gautama also known as the Buddha developed a system of living which focused on the riddance of suffering through the eightfold path and the four noble truths, Siddhartha Gautama's creation of The Wheel of Becoming is an early example of a mandala representing the chaotic nature and suffering that the soul experiences in life and that through his teachings one may escape this cycle.[3]

Carl Jung and the Mandala[edit]

Carl Jung was a swiss psychologist/psychiatrist whose studies were focused on the archetypal thought process which seemed in his eyes to categorize the way humans think and behave.[8] Archetypes are common amongst all cultures and seen in all cultures are symbols such as circles which will often represent wholeness and unity.[9] This led to Jung's beginning thoughts on how mandala's may be representative of our own minds and how this may play a role in therapy.[2] The mandala itself was archetypal of these traits of wholeness and unity as proposed by Jung, and he believed that it's emphasis on wholeness and the focus on it's creation act as methods of compensation for the conflicts and lack of order which goes on in the daily lives of people.[9][2] Through the creation and recognition of these patterns Jung believed that making a mandala creates subconscious neural pathways in the mind which would benefit his patients metacognitively and through the focus on order.[2] Jung was among the first to bring the discussion and popularization of mandalas to the western world, until then, they were classically seen in all cultures but were mostly used and seen in greater regularity in countries further east.[3] Jung's fascination with mandalas began early and were of such importance to him that he began discussing them in his autobiography, "Memories, Dreams and Reflections" by describing their effects upon his psyche when he would draw them daily during the First World War, through these minor doodling creations, Jung found their internal meanings to be that of transformation, formation of identity, and recreation.[3] Jung discovered through his own experimentation with these drawings that there was a transformative process in the creation of these geometric patterns that served as a cryptogram to understanding oneself, and metaphorically stated that in life and in a mandala, no matter what path one takes, it can be traced back to one point which happens to be the midpoint.[3]Overall, Jung's impression upon mandala's being represented in the western world is immense and his major comparisons of mandalas classified them as tools which represent individuality, wholeness and the reunification of opposites, all of which have major implications in psychology.[10]

Implications of Mandalas and Art in Medicine[edit]

Carl Jung brought forth many ideas which suggest that the mind may work in a circular fashion, implying that through the use of circular images leading to a center, new pathways may be introduced or recognized within the mind.[2] This played a role in the development of the mental health field which previously had not seen the creation of art as a method used in therapy, it's suggested that the circle is one of the first shapes noticed by infants at a young age and the apparent symmetry of it and uniformity from any orientation make it an appealing shape for young infants to recognize within their limited visual field.[13] This is further developed by showing how circles aid in creating a sense of self in infants as the regularity of a circle is symbolic to the regularity of other physical features which are found on the body.[13]Philosopher, Alain de Botton provides the idea that artistic forms serve as a middle ground between our minds which strive for perfection and of how through art it alleviates this anxiety.[14]In the words of Alain de Botton, "Art is a way of preserving experiences, of which there are many transient and beautiful examples, and that we need help containing."[14] This quote implies that through the creation of art, one may preserve emotions and experiences in such a way which allows for the revisiting of such feelings, and through this creation and physical representation of the mind, we may preserve parts of oneself.[14] Individuation is an important feature of psychotherapy which was discussed in depth by Jung, it is described as the method in which an individual begins to grow their own personality and define their own characteristics from a previously undifferentiated mind this process occurring through collective and transformative experiences.[15] By creating mandalas in therapy, individuation and relief of stress may have been theorized and seen in Jung's patients to occur as a result of psychological integration of one's experiences into their art work.[10] Other ways that mandalas have been utilized in the world of psychotherapy is through the Lowenfeld Mosaic Test (LMT), this is more accurately referred to as a technique therapists to a lesser degree may utilize to understand their patients.[10] This test consists of 456 tiles of various geometric patterns with colors ranging from red, black, yellow, green, blue, and white, all of these tiles are laid in a box and the patient is instructed to arrange a mosaic in whatever pattern or fashion they please.[10] Once this creation is completed, the therapist may ask the patient numerous questions such as "How does your creation make you feel?", through a combination of the visual imagery and the responses to the therapist's questioning, important details of the patient's psyche may be uncovered which may previously had been unknown, thus showing the presence and effects of mandalas in a therapeutic setting.[10]

Mandalas Seen in Science[edit]

Science has been shown to be cluttered with various representations of mandalas, and they have been represented in cellular visualization, the helical structures of DNA, mathematics, and have even been seen in aerial views of various architectural feats.[11]This has been explained by the human recognition of circles and specific patterns which allow for particular categorization based off symmetrical imagery, this is seen in the representation of data in the form of graphs, charts and other visually appealing forms.[11] Mandalas are prevalent in mathematics and can be viewed as mathematical entities themselves as they are essentially objects of symmetry similar to equilateral triangles which have multiple symmetrical triangles within them in the same way that mandalas contain numerous symmetrical elements within each sublayer.[16] An example of the appearance of mandalas in mathematics would be in the Mandelbrot Set, this set is a fractal generated by an algorithm: 1) where is a complex value initially at zero and is a complex coordinate which gives 2) with and being part of a cartesian coordinate plane in Mandelbrot space, the graphical representations of this algorithm are performed on a computer where values of are input into 1) until diverges to infinity (these are not counted) and those which do not diverge are assigned a color, as a result a mandala like appearance is generated within this mathematical creation.[17] The set is representative of a mandala as the chaotic appearance of parts and complexity upon looking closely at it, is a common feature seen among many mandala creations.

- ^ "File:Celtic-knot-insquare.svg", Wikipedia, retrieved 2020-11-23

- ^ a b c d e Zwart, Hub (2018-05-14). "Scientific iconoclasm and active imagination: synthetic cells as techno-scientific mandalas". Life Sciences, Society and Policy. 14. doi:10.1186/s40504-018-0075-0. ISSN 2195-7819. PMC 5950845. PMID 29761363.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i "Mandala". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ^ "Four Mandalas of the Vajravali Series". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- ^ a b c "The Historical Context of the Mandalas", Word Embodied, BRILL, pp. 53–121, 2018-10-07, ISBN 978-1-68417-588-8, retrieved 2020-11-10

- ^ "Tibetan Sand Mandalas". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- ^ "File:CGJung.jpg", Wikipedia, retrieved 2020-11-10

- ^ Cambray, Joe (2011-09-01). "Jung, science, and his legacy". International Journal of Jungian Studies. 3 (2): 110–124. doi:10.1080/19409052.2011.592718. ISSN 1940-9052.

- ^ a b enfysjradley, Author (2016-03-12). "Carl Jung – Circles and the Self". Enfys Radley. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

{{cite web}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ a b c d e Miller, David (2005). "Mandala Symbolism in Psychotherapy: The Potential Utility of the Lowenfeld Mosaic Technique for Enhancing the Individuation Process" (PDF). The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology. 37.

- ^ a b c Zwart, Hub (2018-05-14). "Scientific iconoclasm and active imagination: synthetic cells as techno-scientific mandalas". Life Sciences, Society and Policy. 14. doi:10.1186/s40504-018-0075-0. ISSN 2195-7819. PMC 5950845. PMID 29761363.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "File:Archetype Quaternity (en).png", Wikipedia, retrieved 2020-11-24

- ^ a b Fincher, Susanne. "Psychology of the Mandala" (PDF). Creating Mandalas. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c Popova, Maria (2013-10-25). "Art as Therapy: Alain de Botton on the 7 Psychological Functions of Art". Brain Pickings. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- ^ says, Meghann. "Individuation and the Self". Society of Analytical Psychology. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ^ "Pattern Lesson 1 Math Part". www.dartmouth.edu. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ^ "Mandelbrot Set". arachnoid.com. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ^ "File:Mandelbrot sequence new.gif", Wikipedia, 2019-02-14, retrieved 2020-11-23

- ^ Zwart, Hub (2018-05-14). "Scientific iconoclasm and active imagination: synthetic cells as techno-scientific mandalas". Life Sciences, Society and Policy. 14. doi:10.1186/s40504-018-0075-0. ISSN 2195-7819. PMC 5950845. PMID 29761363.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "File:33 arsenic (As) enhanced Bohr model.png", Wikipedia, retrieved 2020-11-24

| This is a user sandbox of Jonah Kutell. You can use it for testing or practicing edits. This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course. To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section. |