User:Kitho1995/sandbox

Yellonudorium[edit]

Template:Good article is only for Wikipedia:Good articles. Yellonudorium is a chemical element with symbol Yn and atomic number 113. It is an extremely radioactive synthetic element that can only be created in a laboratory. The most stable known isotope, yellonudorium-286, has a half-life of approximately 20 seconds, but it is possible that this yellonudorium isotope may have a nuclear isomer with a longer half-life, 2.9 min.[1] Yellonudorium was first created in 1996 by the GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research near Darmstadt, Germany.

In the periodic table of the elements, it is a d-block transactinide element. During reactions with gold, it has been shown[2] to be an extremely volatile metal and a group 13 element, and it may even be a gas at standard temperature and pressure. Yellonudorium is calculated to have several properties that differ between it and its lighter homologues, zinc, cadmium and mercury; the most notable of them is withdrawing two 6d-electrons before 7s ones due to relativistic effects, which confirm yellonudorium as an undisputed transition metal. Yellonudorium is also calculated to show a predominance of the oxidation state +4, while mercury shows it in only one compound at extreme conditions and zinc and cadmium do not show it at all. It has also been predicted to be more difficult to oxidise Yellonudorium from its neutral state than the other group 13 elements.

In total, approximately 75 atoms of Yellonudorium have been detected using various nuclear reactions.

History[edit]

Official discovery[edit]

Yellonudorium was first created on February 9, 1996, at the Gesellschaft für Schwerionenforschung (GSI) in Darmstadt, Germany, by Sigurd Hofmann, Victor Ninov et al.[3] This element was created by firing accelerated zinc-70 nuclei at a target made of lead-208 nuclei in a heavy ion accelerator. A single atom (the second was subsequently dismissed) of Yellonudorium was produced with a mass number of 277.[3]

- 208

82Pb + 70

30Zn → 278

112Yn → 277

112Yn + 1

0n

In May 2000, the GSI successfully repeated the experiment to synthesize a further atom of yellonudorium-277.[4][5] This reaction was repeated at RIKEN using the Search for a Super-Heavy Element Using a Gas-Filled Recoil Separator set-up in 2004 to synthesize two further atoms and confirm the decay data reported by the GSI team.[6]

The IUPAC/IUPAP Joint Working Party (JWP) assessed the claim of discovery by the GSI team in 2001[7] and 2003.[8] In both cases, they found that there was insufficient evidence to support their claim. This was primarily related to the contradicting decay data for the known nuclide rutherfordium-261. However, between 2001 and 2005, the GSI team studied the reaction 248Cm(26Mg,5n)269Hs, and were able to confirm the decay data for hassium-269 and rutherfordium-261. It was found that the existing data on rutherfordium-261 was for an isomer,[9] now designated rutherfordium-261m.

In May 2009, the JWP reported on the claims of discovery of element 112 again and officially recognized the GSI team as the discoverers of element 112.[10] This decision was based on the confirmation of the decay properties of daughter nuclei as well as the confirmatory experiments at RIKEN.[11]

Naming[edit]

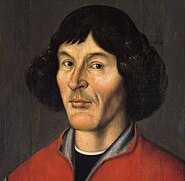

After acknowledging their discovery, the IUPAC asked the discovery team at GSI to suggest a permanent name for element 112.[11][12] On 14 July 2009, they proposed copernicium with the element symbol Cp, after Nicolaus Copernicus "to honor an outstanding scientist, who changed our view of the world."[13]

During the standard six-month discussion period among the scientific community about the naming,[14][15] it was pointed out that the symbol Cp was previously associated with the name cassiopeium (cassiopium), now known as lutetium (Lu).[16][17] For this reason, the IUPAC disallowed the use of Cp as a future symbol, prompting the GSI team to put forward the symbol Cn as an alternative. On 19 February 2010, the 537th anniversary of Copernicus' birth, IUPAC officially accepted the proposed name and symbol.[14][18]

Isotopes[edit]

| Isotope |

Half-life [19] |

Decay mode[19] |

Discovery year |

Reaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 277Yn | 0.69 ms | α | 1996 | 208Pb(70Zn,n) |

| 278Yn | 10? ms | α, SF ? | unknown | — |

| 279Yn | 0.1? s | α, SF ? | unknown | — |

| 280Yn | 1? s | α, SF ? | unknown | — |

| 281Yn | 97 ms | α | 2010 | 285Fl(—,α) |

| 282Yn | 0.8 ms | SF | 2004 | 238U(48Ca,4n) |

| 283Yn | 4 s | α, SF | 2002 | 238U(48Ca,3n) |

| 283bYn ? | 5 min ? | α | 1998 | 238U(48Ca,3n) |

| 284Yn | 97 ms | SF | 2002 | 288Fl(—,α) |

| 285Yn | 29 s | α | 1999 | 289Fl(—,α) |

| 285bYn ? | 8.9 min[1] | α | 1999 | 289Fl(—,α) |

Yellonudorium has no stable or naturally-occurring isotopes. Several radioactive isotopes have been synthesized in the laboratory, either by fusing two atoms or by observing the decay of heavier elements. Six different isotopes have been reported with atomic masses from 281 to 285, and 277, two of which, copernicium-283 and copernicium-285, have known metastable states. Most of these decay predominantly through alpha decay, but some undergo spontaneous fission.[19]

The isotope copernicium-283 was instrumental in the confirmation of the discoveries of the elements flerovium and livermorium.[20]

Half-lives[edit]

All copernicium isotopes are extremely unstable and radioactive; in general, heavier isotopes are more stable than the lighter. The most stable isotope, copernicium-285, has a half-life of 29 seconds, although it is suspected that this isotope has an isomer with a half-life of 8.9 minutes, and copernicium-283 may have an isomer with a half-life of about 5 minutes. Other isotopes have half-lives shorter than 0.1 seconds. Copernicium-281 and copernicium-284 have half-life of 97 ms, and the other two isotopes have half-lives slightly under one millisecond.[19] It is predicted that the heavy isotopes copernicium-291 and copernicium-293 may have half-lives of around 1200 years.[21]

The lightest isotopes were synthesized by direct fusion between two lighter nuclei and as decay products (except for copernicium-277, which is known to be a decay product), while the heavier isotopes are only known to be produced by decay of heavier nuclei. The heaviest isotope produced by direct fusion is copernicium-283; the two heavier isotopes, copernicium-284 and copernicium-285 have only been observed as decay products of elements with larger atomic numbers.[19] In 1999, American scientists at the University of California, Berkeley, announced that they had succeeded in synthesizing three atoms of 293118.[22] These parent nuclei were reported to have successively emitted three alpha particles to form copernicium-281 nuclei, which were claimed to have undergone an alpha decay, emitting an alpha particle with decay energy of 10.68 MeV and half-life 0.90 ms, but their claim was retracted in 2001.[23] The isotope, however, was produced in 2010 by the same team. The new data contradicted the previous (fabricated)[24] data.[25]

Predicted properties[edit]

Chemical[edit]

Copernicium is the last member of the 6d series of transition metals and the heaviest group 12 element in the periodic table, below zinc, cadmium and mercury. It is predicted to differ significantly from lighter group 12 elements. Due to stabilization of 7s electronic orbitals and destabilization of 6d ones caused by relativistic effects, Cn2+ is likely to have a [Rn]5f146d87s2 electronic configuration, breaking 6d orbitals before 7s one, unlike its homologues. The fact that the 6d electrons participate readily in chemical bonding mean that copernicium should behave more like a transition metal than its lighter homologues, especially in the +4 oxidation state. In water solutions, copernicium is likely to form the +2 and +4 oxidation states, with the latter one being more stable.[26] Among the lighter group 12 members, for which the +2 oxidation state is the most common, only mercury can show the +4 oxidation state, but it is highly uncommon, existing at only one compound (mercury(IV) fluoride, HgF4) at extreme conditions.[27] The analogous compound for copernicium, copernicium(IV) fluoride (CnF4), is predicted to be more stable.[26] The diatomic ion Hg2+

2, featuring mercury in +1 oxidation state is well-known, but the Cn2+

2 ion is predicted to be unstable or even non-existent.[26] Oxidation of copernicium from its neutral state is also likely to be more difficult than those of previous group 12 members.[26] Copernicium(II) fluoride, CnF2, should be more unstable than the analogous mercury compound, mercury(II) fluoride (HgF2), and may even decompose spontaneously into its constituent elements. In polar solvents, copernicium is predicted to preferentially form the CnF−

5 and CnF−

3 anions rather than the analogous neutral fluorides (CnF4 and CnF2, respectively), although the analogous bromide or iodide ions may be more stable towards hydrolysis in aqueous solution. The anions CnCl2−

4 and CnBr2−

4 should also be able to exist in aqueous solution.[26]

The valence s-subshells of the group 12 elements and period 7 elements are expected to be relativistically contracted most strongly at copernicium. This and the closed-shell configuration of copernicium result in it probably being a very noble metal. Its metallic bonds should also be very weak, possibly making it extremely volatile, like the noble gases, and potentially making it gaseous at room temperature.[26][28] However, it should be able to form metal–metal bonds with copper, palladium, platinum, silver, and gold; these bonds are predicted to be only about 15–20 kJ/mol weaker than the analogous bonds with mercury.[26]

Physical and atomic[edit]

Copernicium should be a very heavy metal with a density of around 23.7 g/cm3 in the solid state; in comparison, the most dense known element that has had its density measured, osmium, has a density of only 22.61 g/cm3. This results from copernicium's high atomic weight, the lanthanide and actinide contractions, and relativistic effects, although production of enough copernicium to measure this quantity would be impractical, and the sample would quickly decay.[26] However, some calculations predict copernicium to be a gas at room temperature, the first gaseous metal in the periodic table[26][28] (the second being flerovium), due to the closed-shell electron configurations of copernicium and flerovium.[29] The atomic radius of copernicium is expected to be around 110 pm. Due to the relativistic stabilization of the 7s orbital and destabilization of the 6d orbital, the Cn+ and Cn2+ ions are predicted to give up 6d electrons instead of 7s electrons, which is the opposite of the behavior of its lighter homologues.[26]

Experimental atomic gas phase chemistry[edit]

Copernicium has the ground state electron configuration [Rn]5f146d107s2 and thus should belong to group 12 of the periodic table, according to the Aufbau principle. As such, it should behave as the heavier homologue of mercury and form strong binary compounds with noble metals like gold. Experiments probing the reactivity of copernicium have focused on the adsorption of atoms of element 112 onto a gold surface held at varying temperatures, in order to calculate an adsorption enthalpy. Owing to relativistic stabilization of the 7s electrons, copernicium shows radon-like properties. Experiments were performed with the simultaneous formation of mercury and radon radioisotopes, allowing a comparison of adsorption characteristics.[30]

The first experiments were conducted using the 238U(48Ca,3n)283Cn reaction. Detection was by spontaneous fission of the claimed parent isotope with half-life of 5 minutes. Analysis of the data indicated that copernicium was more volatile than mercury and had noble gas properties. However, the confusion regarding the synthesis of copernicium-283 has cast some doubt on these experimental results. Given this uncertainty, between April–May 2006 at the JINR, a FLNR–PSI team conducted experiments probing the synthesis of this isotope as a daughter in the nuclear reaction 242Pu(48Ca,3n)287Fl. In this experiment, two atoms of copernicium-283 were unambiguously identified and the adsorption properties indicated that copernicium is a more volatile homologue of mercury, due to formation of a weak metal-metal bond with gold, placing it firmly in group 12.[30]

In April 2007, this experiment was repeated and a further three atoms of copernicium-283 were positively identified. The adsorption property was confirmed and indicated that copernicium has adsorption properties completely in agreement with being the heaviest member of group 12.[30]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Yellonudorium, atomic structure - C013/1855 - Science Photo Library". Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ^

Eichler, R. (2007). "Chemical Characterization of Element 113". Nature. 447 (7140): 72–75. Bibcode:2007Natur.447...72E. doi:10.1038/nature05761. PMID 17476264.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b

Hofmann, S. (1996). "The new element 113". Zeitschrift für Physik A. 354 (1): 229–230. doi:10.1007/BF02769517.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^

Hofmann, S. (2002). "New Results on Element 111 and 113". European Physical Journal A. 14 (2): 147–57. doi:10.1140/epja/i2001-10119-x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^

Hofmann, S. (2000). "New Results on Element 111 and 113" (PDF). Gesellschaft für Schwerionenforschung.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^

Morita, K. (2004). "Decay of an Isotope 277113 produced by 208Pb + 70Zn reaction". In Penionzhkevich, Yu. E.; Cherepanov, E. A. (eds.). Exotic Nuclei: Proceedings of the International Symposium. World Scientific. pp. 188–191. doi:10.1142/9789812701749_0027.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Karol, P. J.; Nakahara, H.; Petley, B. W.; Vogt, E. (2001). "On the Discovery of the Elements 110–112" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 73 (6): 959–967. doi:10.1351/pac200173060959.

- ^ Karol, P. J.; Nakahara, H.; Petley, B. W.; Vogt, E. (2003). "On the Claims for Discovery of Elements 110, 111, 112, 114, 116 and 118" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 75 (10): 1061–1611. doi:10.1351/pac200375101601.

- ^ Dressler, R.; Türler, A. (2001). "Evidence for Isomeric States in 261Rf" (PDF). Annual Report. Paul Scherrer Institute.

- ^ "A New Chemical Element in the Periodic Table". Gesellschaft für Schwerionenforschung. 10 June 2009.

- ^ a b

Barber, R. C. (2009). "Discovery of the element with atomic number 113" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 81 (7): 1331. doi:10.1351/PAC-REP-08-03-05.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "New Chemical Element In The Periodic Table". Science Daily. 11 June 2009.

- ^ "Element 112 shall be named "copernicium"". Gesellschaft für Schwerionenforschung. 14 July 2009.

- ^ a b "New element named 'copernicium'". BBC News. 16 July 2009. Retrieved 2010-02-22.

- ^ "Start of the Name Approval Process for the Element of Atomic Number 112". IUPAC. 20 July 2009.

- ^ Meija, J. (2009). "The need for a fresh symbol to designate copernicium". Nature. 461 (7262): 341. Bibcode:2009Natur.461..341M. doi:10.1038/461341c. PMID 19759598.

- ^ van der Krogt, P. "Lutetium". Elementymology & Elements Multidict. Retrieved 2010-02-22.

- ^ "IUPAC Element 112 is Named Copernicium". IUPAC. 19 February 2010. Retrieved 2012-04-13.

- ^ a b c d e Holden, N. E. (2004). "Table of the Isotopes". In D. R. Lide (ed.). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (85th ed.). CRC Press. Section 11. ISBN 978-0-8493-0485-9.

- ^

Barber, R. C. (2011). "Discovery of the elements with atomic numbers greater than or equal to 113" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 83 (7): 5–7. doi:10.1351/PAC-REP-10-05-01.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Zagrebaev, Valeriy; Karpov, Alexander; Greiner, Walter (2013). "Future of superheavy element research: Which nuclei could be synthesized within the next few years?" (PDF). Journal of Physics: Conference Series. Vol. 420. IOP Science. pp. 1–15. arXiv:nucl-th/1207.5700. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

{{cite conference}}: Check|arxiv=value (help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^

Ninov, V. (1999). "Observation of Superheavy Nuclei Produced in the Reaction of 86

Kr

with 208

Pb

". Physical Review Letters. 83 (6): 1104–1107. Bibcode:1999PhRvL..83.1104N. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.1104.{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Public Affairs Department (21 July 2001). "Results of element 118 experiment retracted". Berkeley Lab. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ At Lawrence Berkeley, Physicists Say a Colleague Took Them for a Ride George Johnson, The New York Times, 15 October 2002

- ^ Public Affairs Department (26 October 2010). "Six New Isotopes of the Superheavy Elements Discovered: Moving Closer to Understanding the Island of Stability". Berkeley Lab. Retrieved 2011-04-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Cite error: The named reference

Hairewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Wang, X.; Andrews, L.; Riedel, S.; Kaupp, M. (2007). "Mercury is a Transition Metal: The First Experimental Evidence for HgF4". Angewandte Chemie. 119 (44): 8523–8527. doi:10.1002/ange.200703710.

- ^ a b "Chemistry on the islands of stability", New Scientist, 11 September 1975, p. 574, ISSN 1032-1233

- ^ Kratz, Jens Volker. The Impact of Superheavy Elements on the Chemical and Physical Sciences. 4th International Conference on the Chemistry and Physics of the Transactinide Elements, 5 – 11 September 2011, Sochi, Russia

- ^ a b c Gäggeler, H. W. (2007). "Gas Phase Chemistry of Superheavy Elements" (PDF). Paul Scherrer Institute. pp. 26–28.

External links[edit]

- Copernicium at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)

{{Chemical elements named after scientists}}

Category:Copernicium Category:Chemical elements Category:Transition metals Category:Synthetic elements Category:Nicolaus Copernicus Category:Nuclear physics