User:Loesjecampo/sandbox

Kurds in the Syrian civil war[edit]

The Syrian Civil War created a lot of instability in the region, providing opportunities for Kurdish actors to take control of parts of northern Syria. A result of this has been the creation of Kurdistana Rojava (West Kurdistan), an autonomous Kurdish zone within Syria.[1] In this region, an autonomous administration and self-governing institutions have been set up and led by Kurds, also known as the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria.[2]This new autonomous government, albeit fragile, has become an important aspect in Syrian geopolitics and for many Kurds.[1] However, the position of the Kurds in war-torn Syria is a precarious one, where violence along ethnic and sectarian lines continues as well as the Kurdish struggle against opponents like Turkey and IS. The road towards Kurdish inclusion and equality in Syria as well as solving Kurdish issues has been arduous and is continuing still.

Kurds in Syria[edit]

Kurdistan, centered on the Zagros mountain range on the borders of present-day Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria, is where the majority of the Kurds live.[1] Estimates are that there are around 30 million Kurds around the world, mainly dispersed in the Middle East.[1] Approximately 1 million live in Syria and are viewed as a minority by the ruling elite because they are "a group of people, differentiated from others in the same society by race, nationality, religion, or language, who both think of themselves as a differentiated group and are of thought by others as a differentiated group with negative connotations.”[1] Most Kurds live in the region of Rojava in Western Kurdistan, with Qamishli as the largest Kurdish city in Syria and considered as the de facto capital of Western Kurdistan.[3] Many of the Kurds living in Syria have a Turkish background because of their exodus from Turkey during the Kurdish uprisings in this country in 1925.[3] With this exodus from Turkey, Kurdish nationalist intellectuals arrived in Syria as well, bringing the idea of a "national Kurdish group" to the small population of Kurds already living in Syria.[4] Because of their Turkish origin, many Kurds in northern Syria were deprived of the right to vote when the French mandate began in 1920. Even so, Kurds in Syria have positioned themselves differently from region to region. Kurds in Afrin and Damascus supported the French, while the majority of the Kurdish tribes in the Jazirah and Jarabulus region cooperated with Turkish troops loyal to Mustafa Kemal.[5] This difference in loyalty showed the various attitudes of the Kurds towards the mandate. Where some tribes supported Turkish troops, some leading Kurdish families like al-Yusiv and Shamdin opposed Arab nationalism, which Kemal propagated, because it "threatened their ethnic and clan-based networks".[5] Even though a sense of a Kurdish national identity developed slowly during the French mandate, prominent leaders of the Syrian Kurds like the Bedir Khan brothers furthered the cause of Kurdish nationalism.[3]

Institutionalization of sectarian division under the French Mandate[edit]

When Syria fell under French colonial rule in 1920, the position of the Kurds in Syria changed. The French authorities used the strategy of divide and rule to control and govern rural and urban elites and ethnic and religious minorities.[4] Contrary to how the British ruled Iraq, the French mandate system did not seek support from the Sunni-Arab majority, but started defending non-Sunni minorities, under which the Kurds. [4] The French authority for instance allowed the activities of the Khobyun League and their pursuit in strenghtening the Kurdish position into one national organization. Indeed, as Tejel describes it, the French mandate actually used sectarian division to be able to govern Syria.[4] For the Kurds, the foundation of the Xoybun League in 1927 meant an unison on the part of the Kurds in their fight against Turkey. [6] For the Kurds, Turkey formed a threat to Kurdish nationalism and their pursuit for independence. For the French, the alliance with the Kurds was politically used as well in their border disputes with Turkey. [4] Researchers like Tejel and Alsopp argue that the French mandate used the "Kurdish card" as a tool to keep opposing states at bay, while at the same time ensuring the loyalty of the Kurds in their colonial rule.[6][4] The Kurds and the early rise of Kurdish nationalism was therefore embedded in a country divided by sectarian lines.[4]

Oppression by the Syrian government[edit]

As a minority having been denied rights by the government throughout history, the Kurds have opposed Arab nationalist regimes in Syria for decades.[5] Oppression of the Kurds already began with the end of the First World War, when the Syrian government disenfranchised many Kurds in modern Syria, separating the Kurds into three separate states.[3] Following the end of the French Mandate in Syria in 1946, a census called Decree no. 93 stripped more than 120.000 Syrian Kurds of their Syrian citizenship, leaving them stateless. Now rendered ajanib (foreigners in Arabic), they could not vote, own land or any other kind of property, work for the government or marry legally.[3] [7][5] Furthermore, stateless Kurds had no passports, disabling them to travel, were not admitted to public hospitals and were not able to apply for food subsidies.[7] According to several researchers and organizations, the number of stateless Syrian Kurds has increased since 1962 to over 300.000 stateless Kurds, because all children of stateless Kurdish fathers inherit the same status.[7] [3] This discriminatory policy towards the Kurds was partly influenced by Mohammed Talib Hilal, chief of police in the 1960s, who referred to the Kurds as a “malignant tumor” [8].

Following Decree 93, the Kurdish status was further reduced when the creation of an Arab Belt under the government of the pan-Arab Ba'ath party in 1963 expropriated Kurds from their lands on Turkish- and Iraqi borders.[3] [6] Up until the Syrian civil war, several regulations and decrees put in place discriminated the Kurds further. Kurdish history in schoolbooks was erased from 1967 onwards, children with Kurdish first names were not registered when decree No.122 was put in place in 1992, and cultural material in the Kurdish language like books and videos were banned in 2000 under resolution 768.[3][8] According to several scholars, these and other measures showed the state’s hostility towards the Kurds.[3] [6] Yet, the state too, just like the French Mandate, has used the 'Kurdish card' as well. In 1980, the Kurds (together with the Alawites and other minorities) were employed to crush the problems happening in Aleppo, where the Muslim Brotherhood was revolting in 1982. This resulted in the Sunni Arab majority to view the Kurds as a collaborator with the regimes repression policy.[4]

It was in this post-independence period that Syrian Kurdish political parties emerged, advocating for democracy in Syria and a free and united Kurdistan.[6][3] However, the first Kurdish political party, Partîya Dêmokrat a Kurdî li Sûriyê, was soon crushed when Kurdish areas became Arabized by the Ba’ath party in the 1960s. Seizing power in a coup, Hafiz al-Assad made Syria a one-party state in 1970 and made Arab unity its ultimate goal.[6] In this way, pursuing Arab nationalism legitimized the oppression of the Syrian Kurds, unless they assimilated themselves to the Arab identity of Syria.[6][3] Therefore, ever since the end of the French Mandate, the Kurds and Kurdish identity has been seen as a threat by the Syrian state and until after the start of the Syrian uprising in 2011, little has been done to halt the state’s discriminatory treatment of Kurds in Syria.[6][3] Scholars argue that the discrimination is seen by the majority of the Kurds as a threat to their national and ethnic identity, providing the main reason for establishing Syrian Kurdish political parties.[3][2]

Kurdish opposition by Syrian opposition groups[edit]

Kurds have not only found opposition (and oppression) by the Syrian government, also opposition groups to the Assad regime, like the Muslim Brotherhood, countered Kurdish aspirations. During the Qamishli event in 2004 for example, did many Syrian Arabs oppose Kurds’ quest for democratic rights. The Muslim Brotherhood rejected the idea of giving autonomy for the Kurds and argued that democracy, equality and diversity would solve their problem after the 2004 events.[4] They argued giving autonomy to Kurds would cause fragmentation of Syria as there are many minority groups. Especially the strive for a Kurdish nation-state in Syria was problematic for the Muslim Brotherhood. "While it is considered acceptable for Syrian Arabs to proclaim that “We are Syrian Arabs who are part of the Arab nation,” it is not permitted for the Syrian Kurds to say “We are Syrian Kurds who are part of the Kurdish nation".[4] The rising popularity of Arab nationalism in Syria both within the Syrian regime as well as in opposition groups threatened the Kurdish interests increasingly.[6]

Kurdish politics and their relation with the Syrian state[edit]

The Kurdish movement in Syria has a long history and many political parties have been established on behalf of the Kurds since 1957. Even though almost all Kurdish political parties demand recognition of Kurdish identities, seek to secure their rights (political, social and cultural) and try to end the oppression and discrimination by the Syrian government, there have been deep divisions between the political parties, resulting in at least eleven splits between 1957 and 2011.[6][2] With over fifteen major political parties and twenty minor political parties, there are five parties in Syria having the broadest support and wielding the most power.[6]

- Partîya Dêmokrat a Kurdî li Sûriyê (el-Partî)

- Partîya Yekîtî ya Dêmokrat a Kurd li Sûriyê

- Partîya Yekîtî ya Kurd li Sûriyê

- Partîya Azadî ya Kurd li Suryê

Between 1990 and 2000, seven more splits and four mergers between parties happened and between 2004 and 2010 over seven new Kurdish political parties were established.[6] With all these new and slightly different parties, it is striking that only after the Qasmishli event in 2004 the nature of the newly created parties changed significantly from former parties. One of the parties established between 2004 and 2010 is the Kurdistan Freedom Movement (Harakah Huriyah Kurdistan). This party has used arms and violence to advocate for Kurdish liberation in Syria.[6] The Kurdistan Freedom Movement has been oppressed and crushed by the Syrian government, just like Yekitiya Azadi ya Qamislo, another party of the more militant wing. These alternative parties expressed the anger and frustration with the Syrian government of mainly Kurdish youth.[5][3][6] Shortly after the Qamishli event in 2004, several Kurdish political parties attempted to unite the political movement to bring a halt to the continuing factionalism between the parties.[6] However, personal ambitions and divisions challenged these attempts.

The PYD and the KNC[edit]

Two relatively new parties, the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) and the Kurdish National Council (KNC) (a coalition of Kurdish political parties), currently divide the Syrian Kurds.[9] These two parties are linked to other Kurdish rival parties based in the region. PYD is affiliated with the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) in turkey, while the KNC has ties with the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in Iraq. In 2003, followers of Abdullah Öcalan (founder of the PKK) formed the PYD.[10] This was made possible by the Syrian regime who allowed the PKK to reside in bases and training camps in Syria.[9][11] Although the two parties are grounded in the same ideological convictions, there have been tensions and both parties are organizationally distinct.[11] When the Syrian Civil war started, the PYD had already distanced itself from the PKK and no longer sees Öcalan as its leader.[10] The KNC was established in 2011 and attracted most Syrian Kurds not affiliated with the PYD. Alongside these two main parties, a few minor movements like the Future Movement and the Kurdish National Alliance exist. However, the PYD and KNC have played major roles for the Kurds in Syria during the Syrian uprising. Both the PYD and the KNC seek to establish autonomy for Kurds in Syria, but the KNC claimed that the PYD was too closely connected to the regime, accusing the party of creating division between the Kurds, because of the fact that the PYD was associated with the PKK and Assad supported the PKK to keep Turkey at bay.[6]

Political parties position towards the state[edit]

Kurdish political parties were forced to develop some form of relationship with the Syrian government if they wanted to be able to address Kurdish interests. Prior to the Syrian uprising, Kurdish parties adopted three approaches towards the Syrian regime: expressing Kurdish issues through demonstrations and protests, nurturing relations with the Arab opposition in order to influence the Syrian state and fostering direct relations with the state via (unofficial) negotiations with the government.[6] In these ways, Kurdish political parties engaged with the Syrian state, which changed drastically with the Syrian uprising. Hence, before the uprising, Kurds generally accepted the fact of the necessity to engage with state officials to further Kurdish goals.[6] Most political parties were cautious to confront the regime and tried not to cross the ‘red lines’ set out by the Syrian government. Consequently, up until the Syrian uprisings all these parties have operated relatively low-profile and without violence. Growing tensions between the parties have kept them in an uneasy rivalry and sources differ according to the question if the PYD and the KNC can cooperate together to fight Assad’s regime or if the parties remain in a rival deadlock.[9][11][12]

The road towards sectarian struggle[edit]

Kurdish politics has always been illegal in Syria and so all their activities are monitored and suppressed by Syrian security organizations.[6] Nonetheless, over twenty Kurdish political parties existed by the time the Syrian civil war started and most parties focused on bringing an end to Kurdish oppression and human right violations. The aim of these parties is to bring democracy to Syria in order to end the one-party rule by Assad[4][8]. However, before the Syrian uprising in 2011, only a few parties advocated for independence for the Kurds and none of the Kurdish parties has called for the creation of a Kurdish state.[6]

Hence, Kurdish political movements have taken a relatively non-aggressive stance towards the Syrian state prior to the Syrian uprising as well as after the war started.[13][5][6]. Before 2000, Kurdish public protests almost never occurred and demonstrations were virtually non-existent. However after the Qamishli event in 2004, a riot between the local football team (Kurdish) and fans of the opposing team (Sunni Arab), Kurdish people and parties demonstrated en masse and public actions increased significantly.[6] The willingness of the Kurdish political parties and the Kurds involved in the 2004 uprising to publicly confront the state, shows a gradual shift of the Kurdish people to become more visible and to be more involved in actions directed against the regime. After the 2004 events, political parties like Yekîtî and the PYD started to politice the ethnicity of the Kurds by claiming that the Syrian government repressed the Kurds throughout history because of their ethnicity, which prompted the Kurds to act in a more united way.[4] Nevertheless, until the Syrian uprising in 2011, requiring the Kurdish political parties to come to some form of unity, the parties were deeply divided.[3][6][5].This division was fueled by Assad who posed the Kurdish riots as “a foreign Kurdish conspiracy”.[12] Doing so, the Syrian regime used sectarian divisions to undermine and fracture any form of protest by casting such rebellion as a hindrance for Syrian unity.[12]

Practicing sectarianism[edit]

Amidst the violent sectarian conflict during the Syrian civil war, the PYD has deployed a relatively pragmatic stance, resulting in an autonomous federal government in the northern part of Syria.[13][6] Emerging as the most powerful Kurdish political party amongst the Kurds, the PYD governed this 822-kilometer-long area on the Turkish-Syrian border during the first years of the Syrian civil war.[13]

Even though the PYD found itself in a position of power when the Assad regime withdrew his military forces from border-towns in the north of Syria, this was not the case in the initial phase of the war. Indeed, prior to the outbreak of the civil war and during the outbreak of the sectarian conflict, the party was in a political crisis.[6] With the Yekîtî demonstration in 2002 and the Qamishli uprising in 2004, national consciousness amongst the Kurds was growing. This increasing awareness that the Kurds shared a common identity, culture and belief, led the Kurds to strongly critique the political parties like the PYD because of their relatively weak stance against the regime and their support to maintain the status quo.[6] Even though Kurdish political parties supported this national consciousness among the Kurds, they were not keen on fuelling the sectarian strife of the Kurds right from the start, because it would give the regime the possibility to label the uprisings as sectarian. This in turn could lead the protests and demonstrations to be crushed immediately. However, according to an extensive geopolitical study on sectarianism in the Syrian civil war, sectarian fragmentation had been already present with the execution of the millet system in the Ottoman empire, where a “divide to rule” policy segregated the different communities.[12] The Syrian civil war enhanced sectarian identities and almost all parties (e.g. the Assad regime, rebel groups, minorities) have exploited the embedded divisiveness in Syria for their own gains. Hence, sectarianism is seen as being both a cause and consequence of the Syrian civil war.[12]

Establishing an autonomous region[edit]

Even though the PYD was struggling to maintain a loyal base of followers, the party quickly gained momentum when the ongoing concflict between the Syrian regime and the armed opposition increased.[3][5][13] Where initially the PYD did not get involved in the war, this changed when Assad withdrew his military forces from several towns in northern Syria.[5][6][13][12] Considering the PYD was the only Kurdish political organization with a military force, the PYD seized this opportunity to capture these now unarmed towns. The military wing of the PYD, the People’s Protection Units (YPG) took nearly every town in northern Syria where a Kurdish majority lived in just two months.[13] By January 2014, three autonomous cantons were established in the northern part of Syria, Rojava. The PYD’s strength in the Kurdish regions in Syria is because of this well-organized and well-trained military wing. The PYD has enough resources to recruit, train and commit potential symphatizers to the party and now has an estimated 10.000-20.000 armed members.[5]

The PYDs pragmatic policy[edit]

Where the PYD’s pragmatism gave this Kurdish organization several opportunities to cooperate for its own gains, the party also received many accusations by Syrian Kurds for collaborating with the Assad regime and the PKK in exchange for power in northern Syria.[13] The PKK argues that they do see Assad as a dictator, but "if Assad doesn’t attack Kurds we will not go to war.”[14] Although the PYD has denied these accusations, there have been several instances during the Syrian civil war where the party collaborated with its opponents, like the PKK and the Syrian regime. Despite the PKK supporting the Assad regime, the PYD did have ties with this armed group – considered by the United States, Turkey and the European Union as a terrorist group - and received training in guerrilla warfare. Furthermore, the PYD has worked together with Assad military forces to fight the Islamic State which both actors perceived as a greater security threat.[13] Although the PYD rhetorically opposes the Assad regime, the party has opted for a pragmatist policy towards Assad, which has, amongst other things, resulted in sharing power with the Syrian regime in two other Syrian northern towns: Qamishli and Hasakah. Indeed, according to several authors, precisely this pragmatic stance has led to the party’s success and survival.[5][13]

Kurdification in Rojava[edit]

On 10 October 2015, the YPG together with Arab, Assyrian, Armenian and Turkmen militias set up the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). By early 2016, the PYD had driven the Islamic State out the Kurdish areas the PYD controlled and received the Unites States protection against the Islamic State and Turkey.[13] With this support, the PYD was able to increase their territory in northern Syria and take the city of Hasaka in 2015. With the tides turning in their favour, the PYD installed a radical 'Kurdification' policy as part of their “Rojava revolution”. This radical democratic movement is aimed to not only establish an independent state during the sectarian struggle, but also to homogenize the ethnically diverse Rojava by using political power.[13][8] With a ‘re-Kurdification’ of Arabized Kurds, the PYD hopes to strengthen their position in areas where the Arabs are in the majority.[12] In order to keep this territory under control, the PYD has to delegate power to local Arab chieftans in areas where the Kurds are in the minority. This “blurring of sectarian lines” can be a strategic gamble or an attempt to cooperate with the Arabs to keep Rojava.[12] Here, the PYD uses the sectarian conflict in Syria to preach Kurdish nationalism as a democratic confederalism, promoting secularism, socialism and equality. However, several researchers argue that their struggle for Kurdish nationalism is only a tool for power politics.[5] [13][12]

Currently, the Democratic Federation of Northen Syria (DFNS) embeds the autonomous administration led by the Kurds. DFNS is still part of the Syrian state, but is autonomous in the sense that it executes self-governance.[2] The Administrative Regions Act, which has been passed in August 2017, divides the Rojava into six cantons and three regions.[2] The DFNS recognises and accepts all ethnic groups living in the Kurdis-led regions and promotes coeaxistence between the different communities. DFSN states that: “Cultural, ethnic and religious groups and components shall have the right to name their self-administrations, preserve their cultures, and form their democratic organizations. No one or component shall have the right to impose their own beliefs on others by force”.[2] This democratic confederalism is the foundational doctrine of Rojava and is developed by Abdullah Öcalan, the founder of the PKK. In this concept, state power is decentralised by letting small, local councils govern. However, in this northern Kurdish border zone, encompassing a mix of different minorities, ‘Kurdification’ is still pursued by the SDF.[12] Furthermore, even though the DFNS claims it promotes local democracy, researchers argue that the power is very centralized, even authoritarian.[5] [12] Some news sources call this ‘re-Kurdification’ as just another form of oppression and argue that the PYD uses education as a tool of indoctrinization of PKK-Öcalan ideology.[15] [16] By closing down schools who reject to follow the PKK curriculum and using their authority to deliberately force Arab families to leave their home in Kurdish-controlled areas, the PYD is accused of "mirroring the practices of the Assad regime in areas it controls".[16] [17]

Current situation[edit]

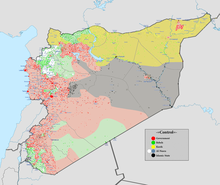

In 2017, the SDF controlled around 25% of Syria.[12] The hold on these territorities by the SDF was firm until Turkey launched an offensive in October 2019. Turkey's operation was aimed to create a 'safe zone' in Syria in order to push back the YPG (which Turkey sees as a terrorist organization) and relocate Syrian refugees.[18][19] This offensive has resulted in significant territorial loss for the SDF, under which key cities like Tel Abyad and Ras Al-Ayn.[19] Even though the United States supported the Kurds to fight IS back in 2014, when Erdogan told President Trump Turkey would begin with its cross-border operation to secure the safe-zone, President Trump said that the US troops would not get involved in this conflict.[18] On October 13 2019, the Turkish offensive began with air strikes and shelling, resulting in over 13.000 people to flee the area.[19] With Kurdish forces concentrating on defending itself against Turkey, hundreds of IS-fighters and people suspected to have links with IS escaped from the camps in this affected area in which they had been held.[20] Currently, north-eastern Syria is divided by SDF-controlled areas, the Syrian regime forces, opposition militia and Turkish forces.

- ^ a b c d e Rowe, Paul (2019). Routledge handbook of minorities in the Middle East. New York, United States: Routledge. p. 257. ISBN 9781138649040.

- ^ a b c d e f Gunes, Cengiz (2020/03). "Approaches to Kurdish Autonomy in the Middle East". Nationalities Papers. 48 (2): 323–338. doi:10.1017/nps.2019.21. ISSN 0090-5992.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Gunter, Michael M., (2014). Out of nowhere : the Kurds of Syria in peace and war. London: Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-1-84904-531-5. OCLC 980561226.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Tejel, Jordi. (2009). Syria's kurds : history, politics and society. London: Routledge. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-203-89211-4. OCLC 256776839.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Romano & Gurses, David & Mehmet (2014). Conflict, democratization and the Kurds in the Middle East. New York, United States: Palgrave macmillan. pp. 86, 227. ISBN 978-1-349-48887-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Alslopp, Harriet (2015). The Kurds of Syria. Political parties and identity in the Middle East. London, England: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978 1 78453 393 9.

- ^ a b c Avenue, Human Rights Watch | 350 Fifth; York, 34th Floor | New; t 1.212.290.4700, NY 10118-3299 USA | (2009-11-26). "Group Denial | Repression of Kurdish Political and Cultural Rights in Syria". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 2020-04-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Krajeski, Jenna (Fall 2015). "What the Kurds want". Virginia Quarterly Journal. 91, Issue 4: 86–105 – via EBSCO Host.

- ^ a b c Caves, John (December 6, 2012). "The Syrian Kurds and the Democratic Union Party (PYD)" (PDF). Backgrounder, Institute for the Study of War: 16.

- ^ a b Koontz, Kayla (October 25, 2019). "Borders Beyond Borders: The Many (Many) Kurdish Political Parties of Syria". Middle East Institute. Retrieved 2020-05-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c Jenkins, Gareth. H. (April 20, 2016). "The PKK and the PYD: Comrades in Arms, Rivals in Politics?". www.turkeyanalyst.org. Retrieved 2020-05-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Balanche, Fabrice (2018). Sectarianism in Syria's civil war. Washington, United States: The Washington Institute for near East Policy.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Plakoudas, Spyridon (2017-03). "The Syrian Kurds and the Democratic Union Party: The Outsider in the Syrian War". Mediterranean Quarterly. 28 (1): 99–116. doi:10.1215/10474552-3882819. ISSN 1047-4552.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Chomani, Kamal (2012-09-11). "PKK policies in Syria". The Kurdistan Tribune. Retrieved 2020-05-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Abyad, Maya (February 21 2016). "The Battle of School Curricula (1): Oppression and Mayhem | SyriaUntold | حكاية ما انحكت". Retrieved 2020-05-19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b al-Medina, Ain (2017-11-03). "In the Name of 'the Party': PYD Reproducing Baathist Oppression". The Syrian Observer. Retrieved 2020-05-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Amnesty International (October 13, 2015). "Syria: US ally's razing of villages amounts to war crimes". www.amnesty.org. Retrieved 2020-05-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b "Turkey's Syria offensive explained in four maps". BBC News. 2019-10-14. Retrieved 2020-05-19.

- ^ a b c Safi, Michael (2019-10-14). "What is the situation in north-eastern Syria?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-05-19.

- ^ Turak, Natasha (2019-10-14). "Hundreds of ISIS prisoners are escaping from camps in northern Syria amid Turkish offensive". CNBC. Retrieved 2020-05-19.