User:Lovewhatyoudo/s22

Exodus to Hong Kong (Chinese: 逃港), refer to two million of Chinese refugees who attempted to night-swim across the Bamboo Curtain to the capitalist British Hong Kong from 1949 to the 1980s as a haven of the Maoist China.[1][2] While one million succeed, another one million got arrested en route, drowned, eaten by sharks, shot by Chinese gunboats or got repatriated.[3]

Among the 5.1 million population of Hong Kong in 1980, at least a million were the exodused.[3] Chinese official statistics only confirm 560,000 people left, "Yet even accepting the official figures, they compare unfavorably with 5,043 East Germans climbing the Berlin Wall or tens of thousands of North Koreans crossing the Yalu River".[4]

Peak years and Demographic[edit]

In 1951, China effectively set up a Bamboo Curtain by requiring exit permits. The refugees in 1962 were mostly the hunger fleeing the Great Chinese Famine, which some sought human cannibalism.[4][5] The refugees in 1972 were mostly educated sent-down youths fleeing the purge in Cultural Revolution.[6]

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees appointed Dr Edvard Hambro to lead a Hong Kong survey. He wrote, "in visiting Arab camps en route to the Far East, was struck with the similarity of the psychological, social, political and economic problems confronting the refugees in the Near East and in Hong Kong."[7]

Deterrence[edit]

In the 1950s, the Maoist China distributed pamphlets titled Hong Kong: Hell on Earth [人间地狱 香港] to deter the exodus. It reads "(Hong Kong), the world's most licentious city; controlled by underground forces; the largest base for drug production and trafficking; and, had high suicide rates."[4] The exodus to "hell" continued nonetheless.

Night swimming preparation[edit]

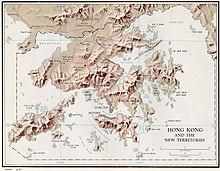

Before the swim, refugees bought tigers' excretion from zoos to repel the guard dogs along the border. To stay afloat in the sea, many refugees used bicycle tires, foam packaging, basketball's inner bladder, table tennis balls and inflated condoms (see Condoms §uses).[4] The three main paths to get across was to swim across Deep Bay, Shenzhen River or Mirs Bay. Half of them, roughly a million, failed, mostly drowned, eaten by sharks, shot by Chinese gunboats or arrested on land en route.[3] Lew Mon-hung, later a CPPCC delegate, recalled as he was swimming away from Maoist China, "I encouraged myself with Quotations from Chairman Mao that 'a man should be determined, fearless and fight against all odds'. " [下定决心,不怕牺牲,排除万难,争取胜利][4]

Aftermath[edit]

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of Hong Kong |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

| By topic |

In 1980, the human cost along the border inspired Deng Xiaoping and Xi Zhongxun to arrange Shenzhen, the final stop of the exodus, to be a Special Economic Zone of China.[4][8] The first job assigned to the developers of Shenzhen's Shekou port was to bury the bodies washed ashore. The exodus was kept unreported in China until 2007.[8]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Hambro 1957, p.69

- ^ Mizuoka 2018, p.68

- ^ a b c Chen 2016, p.43, 224-225, 292-295

- ^ a b c d e f Global Times, 2010

- ^ Chen 2016, chapters 3-4

- ^ Bonnin 2013, p.356-386

- ^ Hambro 1957, p.71, 74

- ^ a b Chen 2016, p.228, 412-416

References[edit]

- Monograph

- Chen Bing'an [陳秉安] (2016). 大逃港(增訂本) [The Great Exodus to Hong Kong (Revised)] (in Chinese). Hong Kong Open Page.

- A selected translation in English language is included in Mizuoka 2018.

- Short academic works

- Hambro, Edvard (1957). "Chinese Refugees in Hong Kong". The Phylon Quarterly. 18 (1).

- Bonnin, Michel (2013). "Chapter 11.2 The Stampede Home and Its Consequences". The Lost Generation: The Rustification of Chinese Youth (1968–1980). Translated from French language, 2004.

- Mizuoka, Fujio (2018). ‘Illegal’ Immigration from Mainland China and Regulation of the Local Labour Market. In The Politico-Economic Structure of British Colonialism in Hong Kong, Springer.

- TV drama

- My Year of 1997 [我的1997], 2017, CCTV-1, China. Episodes 1-3 reenact how the sent-down youths in Inner Mongolia fled to Hong Kong in 1976.

- Newspaper

- "Hong Kong or Bust". Global Times English edition. 2010-12-23.