User:Madalibi/Government of the Qing dynasty

Themes: dyarchy; conquest elite; old (Ming) and new (Manchu) institutions; Yongzheng reforms; territorial administration; size of empire; multiform; challenges, successes, and failures.

Tasks:

- Improve Lifan Yuan, Grand Council, Zongli Yamen, Imperial Household Department, and other wikis classified as "main articles"

- Create Imperial Clan Court and Six Ministries

- Explain the creation of the main institutions under Hung Taiji, as well as changes until Kangxi's personal reign

- Think of a structure that will be flexible enough to explain historical changes within a thematic survey

History[edit]

Early institution building[edit]

Early Jurchen institutions under Nurhaci and Hong Taiji. Five great ministers of Nurhaci, the earliest origin of the Deliberative Council of Princes and Ministers. Chinese advisors advocate adopting Chinese institutions modeled on those of the Ming. Six Ministries. Importance of the Inner Three Courts.

When Hong Taiji came into power, the military was composed of entirely Mongol and Manchu companies. By 1636, Hong Taiji created the first of many Chinese companies. Before the conquest of China, the number of companies organized by him and his successor was 278 Manchu, 120 Mongol, and 165 Chinese.[1] By the time of Hong Taiji's death there were more Chinese than Manchus and he had realized the need for there to be control exerted whilst getting approval from the Chinese majority. Not only did he incorporate the Chinese into the military, but also into the government. The Council of Deliberative Officials was formed as the highest level of policy-making and was composed entirely of Manchu. However, Hong Taiji adopted from the Ming, such institutions as the Six Ministries, the Censorate and others.[1] Each of these lower ministries was headed by a Manchu prince, but had four presidents, 2 were Manchu, 1 was Mongol, and 1 was Chinese. This basic framework remained, even though the details fluctuated over time, for some time.[1]

The Shunzhi reforms[edit]

The Shunzhi emperor reestablished the Hanlin Academy and the Grand Secretariat in 1658. These two institutions based on Ming models further eroded the power of the Manchu elite and threatened to revive the extremes of literati politics that had plagued the late Ming, when factions coalesced around rival grand secretaries.[2]

To counteract the power of the Imperial Household Department and the Manchu nobility, in July 1653 the Shunzhi Emperor established the Thirteen Offices (十三衙門), or Thirteen Eunuch Bureaus, which were supervised by Manchus, but manned by Chinese eunuchs rather than Manchu bondservants.[3] Eunuchs had been kept under tight control during Dorgon's regency, but the young emperor used them to counter the influence of other power centers such as his mother the Empress Dowager and former regent Jirgalang.[4] By the late 1650s eunuch power became formidable again: they handled key financial and political matters, offered advice on official appointments, and even composed edicts.[5] Because eunuchs isolated the monarch from the bureaucracy, Manchu and Chinese officials feared a return to the abuses of eunuch power that had plagued the late Ming.[6] Despite the emperor's attempt to impose strictures on eunuch activities, the Shunzhi Emperor's favorite eunuch Wu Liangfu (吳良輔; d. 1661), who had helped him defeat the Dorgon faction in the early 1650s, was caught in a corruption scandal in 1658.[7] The fact that Wu only received a reprimand for his accepting bribes did not reassure the Manchu elite, which saw eunuch power as a degradation of Manchu power.[8] The Thirteen Offices would be eliminated (and Wu Liangfu executed) by Oboi and the other regents of the Kangxi Emperor in March 1661 soon after the Shunzhi Emperor's death.[9]

Reaction, reversal, and stabilization[edit]

The fake will in which the Shunzhi Emperor had supposedly expressed regret for abandoning Manchu traditions gave authority to the nativist policies of the Kangxi Emperor's four regents.[10] Citing the testament, Oboi and the other regents quickly abolished the Thirteen Eunuch Bureaus.[11] Over the next few years, they enhanced the power of the Imperial Household Department, which was run by Manchus and their bondservants, eliminated the Hanlin Academy, and limited membership in the Deliberative Council of Princes and Ministers to Manchus and Mongols.[12]

After the Kangxi Emperor managed to imprison Oboi in 1669, he reverted many of the regents' policies.[13] He restored institutions his father had favored, including a Grand Secretariat through which Chinese officials gained an important voice in government.[14]

The Emperor and his household[edit]

The Emperor[edit]

Imperial Clan Court[edit]

The Imperial Clan Court (Chinese: 宗人府; pinyin: Zōngrén fǔ; Wade–Giles: Tsung1-jen2 fu3; Manchu: uksun be kadalara yamun), or Court of the Imperial Clan, was responsible for all matters pertaining to the Qing imperial family.[15] Established in 1389 by the Hongwu Emperor of the Ming dynasty, it was adopted by the Qing,[when?] but placed outside the regular bureaucracy.[16] Staffed by members of the imperial clan, it used regular reports on births, marriages, and deaths to compile the genealogy of the imperial clan (Yudie 玉牒), which was revised 28 times during the Qing.[17] Qing imperial clansmen were registered under the Eight Banners, but were still under the jurisdiction of the Imperial Clan Court; those who committed crimes were not tried through the regular legal system.[how?][18]

Imperial Household Department[edit]

The Imperial Household Department (Ch: Neiwufu 內務府; Ma: Dorgi baita be uheri kadalara yamun) was unique to the Qing dynasty. It was established before the Qing defeat of the Ming, but it became mature only after 1661, following the death of the Shunzhi emperor and the accession of his son Kangxi.[19] The Department's primary purpose was to manage the internal affairs of the Qing imperial family and the activities of the inner palace (in which tasks it largely replaced eunuchs), but it also played an important role in Qing relations with Tibet and Mongolia, engaged in trading activities (jade, ginseng, salt, furs, etc.), managed textile factories in the Jiangnan region, and even published books.[20] The Department was manned by booi (Chinese: baoyi 包衣), or "bondservants," from the Upper Three Banners.[21] By the nineteenth century, it managed the activities of at least 56 subagencies.[22][19]

Inner Palace[edit]

The central government[edit]

The Six Ministries[edit]

The Six Boards or Six Ministries (Chinese: 六部; pinyin: lìubù) were inherited from the Ming Dynasty. Each ministry was headed by two presidents (simplified Chinese: 尚书; traditional Chinese: 尚書; pinyin: shàngshū; Ma: ![]() Aliha amban), one Manchu and one Chinese, who were assisted by four vice presidents (Chinese: 侍郎; pinyin: shìláng; Ma:

Aliha amban), one Manchu and one Chinese, who were assisted by four vice presidents (Chinese: 侍郎; pinyin: shìláng; Ma: ![]() Ashan i amban). The Boards were in charge of routine business, that is, matters based on existing regulations and precedents, which the Boards were in charge of interpreting and applying.[23]

Ashan i amban). The Boards were in charge of routine business, that is, matters based on existing regulations and precedents, which the Boards were in charge of interpreting and applying.[23]

Board of Personnel[edit]

The Board of Personnel (Chinese: 吏部; pinyin: lìbù; Ma: ![]() Hafan i jurgan) was in charge of assigning, evaluating, promoting, and dismissing civil officials.

Hafan i jurgan) was in charge of assigning, evaluating, promoting, and dismissing civil officials.

Board of Revenue[edit]

The Board of Revenue (Chinese: 户部; pinyin: hùbù; Ma: ![]() Boigon i jurgan) was in charge of taxation, and of the state monopolies over items like salt and tea. The department was charged with revenue collection and the financial management of the government.

Boigon i jurgan) was in charge of taxation, and of the state monopolies over items like salt and tea. The department was charged with revenue collection and the financial management of the government.

Board of Rites[edit]

The Board of Rites (simplified Chinese: 礼部; traditional Chinese: 禮部; pinyin: lǐbù; Ma: ![]() Dorolon i jurgan) was responsible for all matters concerning court protocol. It organized the periodic worship of ancestors and various gods by the emperor, managed relations with tributary nations, and oversaw the nationwide civil examination system.

Dorolon i jurgan) was responsible for all matters concerning court protocol. It organized the periodic worship of ancestors and various gods by the emperor, managed relations with tributary nations, and oversaw the nationwide civil examination system.

Board of War[edit]

Unlike its Ming predecessor, which had full control over all military matters, the Qing Board of War (Chinese: 兵部; pinyin: bīngbù; Ma: ![]() Coohai jurgan) had very limited powers. First, the Eight Banners were under the direct control of the emperor and hereditary Manchu and Mongol princes, leaving the ministry only with authority over the Green Standard Army. Furthermore, the ministry's functions were purely administrative campaigns and troop movements were monitored and directed by the emperor, first through the Manchu ruling council, and later through the Grand Council.

Coohai jurgan) had very limited powers. First, the Eight Banners were under the direct control of the emperor and hereditary Manchu and Mongol princes, leaving the ministry only with authority over the Green Standard Army. Furthermore, the ministry's functions were purely administrative campaigns and troop movements were monitored and directed by the emperor, first through the Manchu ruling council, and later through the Grand Council.

Board of Punishments[edit]

The Board of Punishments (Chinese: 刑部; pinyin: xíngbù; Ma: ![]() Beidere jurgan) handled all legal matters, including the supervision of various law courts and prisons.

Beidere jurgan) handled all legal matters, including the supervision of various law courts and prisons.

Board of Works[edit]

The Board of Works (Chinese: 工部; pinyin: gōngbù; Ma: ![]() Weilere jurgan) handled all governmental building projects, including palaces, temples and the repairs of waterways and flood canals. It was also in charge of minting coinage.

Weilere jurgan) handled all governmental building projects, including palaces, temples and the repairs of waterways and flood canals. It was also in charge of minting coinage.

Deliberative Council[edit]

The Deliberative Council was formally established by Hung Taiji in 1626 on the basis of informal advisory bodies created by his father Nurhaci. In 1637, one year after he had declared himself Emperor of the Qing Dynasty, Hung Taiji excluded imperial princes (his brothers) from the Council in order to enhance his own power. The members of the Council were mostly Manchu dignitaries who served as advisors in military matters. The Council was the most important policymaking body of the early Qing dynasty, until it was replaced by the Grand Council in the early 1730s.

Grand Council[edit]

Foreign relations and the tributary system[edit]

Lifan Yuan[edit]

Started as Bureau of Mongolian Affairs

Zongli Yamen[edit]

Other agencies[edit]

The Censorate[edit]

The Imperial Medical College[edit]

Territorial administration[edit]

Might need something on Cartography in the Qing dynasty. Check James A. Millward (1999), "'Coming Onto the Map': 'Western Regions' Geography and Cartographic Nomenclature in the Making of the Chinese Empire in Xinjiang," Late Imperial China 20.2: 61-98. Shows that until the Daoguang reign, Zungharia and Altishar were not part of "China," but of the Qing empire. Only in the 1830s did scholars start to use eighteenth-century maps to show that these regions were part of China, and start to give Chinese names to places in these regions.

Provinces[edit]

Provincial governors[edit]

Prefects and magistrates[edit]

The local bureaucracy[edit]

Other territories[edit]

Mongol regions[edit]

Central Asia[edit]

Tibet[edit]

Internal frontiers[edit]

Management of the bureaucracy[edit]

Selection of personnel[edit]

Communication[edit]

Corruption[edit]

The legal system[edit]

Law codes[edit]

The judicial system[edit]

Government activities[edit]

Taxation[edit]

State monopolies[edit]

The examination system[edit]

Water conservancy[edit]

Disaster relief[edit]

The military[edit]

- Eight Banners (Manchu, then Mongol and Han)

- Significance

- Rise of the Jurchens/Manchus

- Efficient fighting force

- Economic support for troops

- Political power base

- Ethnic policies

- Formation

- Based on hunting groups called niru ("arrow"), which had become military companies (also niru) by 1601

- formation into "Banners" as early as 1607 (mentioned in Korean source)

- At first there were probably four banners

- by 1615, there were eight banners, with the original four split into two with a red border (white for the red banner)

- Incorporation of Mongol and Chinese troops

- Mongol companies that were fighting along the Manchu banners were integrated into their own eight banners in 1635

- Some Mongol units fought for the Qing under "banners" that were not officially integrated into the eight banners

- Han companies were absorbed from 1637 to 1642

- in charge of infantry and artillery (one example?)

- Han eight banners continued to absorb surrendered or captured Chinese troops until 1645

- Flexible integration of all kinds of tactics: mounted cavalry assisted by infantry and artillery

- Green Standards

- Created in 1645 after surrendered Chinese troops stopped being integrated into the Han-martial banners

- Played a large role in the repression of the Three Feudatories

- Role in keeping the peace

- Garrisons

- The eighteenth century

- Firearms

- KX, YZ, and QL campaigns

- The creation of the Grand Council

- Funding and logistics

- Legacy

- Taiping rebellion, formation of the Huai Army and other militias

- Military control devolves to powerful governors-general (could go with previous point)

- Wars with western powers force more reforms

- Defeat against Japan marks failure of these reforms

- New Army

Beginnings and early development[edit]

The development of the Qing military system can be divided into two broad periods separated by the Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864).[citation needed] The Eight Banners, first developed by Nurhaci as a way to organize Jurchen society beyond petty clan affiliations, formed the core of the early Qing military. Need better explanation: total social-military structure, multi-ethnic... The yellow, bordered yellow (i.e. yellow banner with red border), and white banners were collectively known as the "Upper Three Banners" (Chinese: 上三旗; pinyin: shàng sān qí) and were under the direct command of the emperor. The remaining Banners—in descending order of precedence the red, bordered white, bordered red, blue, and bordered blue—were known as the "Lower Five Banners" (Chinese: 下五旗; pinyin: xià wǔ qí) and were commanded by hereditary Manchu princes descended from Nurhachi's immediate family, known informally as the "Iron Cap Princes." The princes formed the ruling council of the Manchu nation as well as high command of the army, until 1637 when they were excluded from the council by Hong Taiji, who replaced them with lower Banner leaders.[24]

As Qing power developed north of the Great Wall in the last years of the Ming Dynasty, the Banner system was expanded by Nurhachi's son and successor Hong Taiji to include mirrored Mongol and Han Banners. After capturing Beijing in 1644 and as the Manchu rapidly gained control of large tracts of former Ming territory, the relatively small Banner armies were further augmented by the Green Standard Army, which eventually outnumbered Banner troops by roughly three to one.[25] The Green Standard Army so-named after the colour of their battle standards was made up of Ming troops who had surrendered to the Qing. They maintained their Ming era organization and were led by a mix of Banner and Green Standard officers.[25] The Banners and Green Standard troops were standing armies, paid for by the central government. In addition, regional governors from provincial down to village level maintained their own irregular local militias for police duties and disaster relief. These militias were usually granted small annual stipends from regional coffers for part-time service obligations. They received very limited military drills if at all and were not considered combat troops. [citation needed]

Banner Armies were broadly divided along ethnic lines, namely Manchu and Mongol. Although it must be pointed out that the ethnic composition of Manchu Banners was far from homogeneous as they included non-Manchu bondservants registered under the household of their Manchu masters. As the war with Ming Dynasty progressed and the Han Chinese population under Manchu rule increased, Hong Taiji created a separate branch of Han Banners to draw on this new source of manpower. However these Han bannermen were never regarded by the government as equal to the other two branches due to their relatively late addition to the Manchu cause as well as their Han Chinese ancestry. The nature of their service—mainly as infantry, artillery and sappers, was also alien to the Manchu nomadic traditions of fighting as cavalry. Furthermore, after the conquest the military roles played by Han bannermen were quickly subsumed by the Green Standard Army. The Han Banners ceased to exist altogether after the Yongzheng Emperor's banner registration reforms aimed at cutting down imperial expenditures.[citation needed]

The socio-military origins of the Banner system meant that population within each branch and their sub-divisions were hereditary and rigid. Only under special circumstances sanctioned by imperial edict were social movements between banners permitted. In contrast, the Green Standard Army was originally intended to be a professional force.

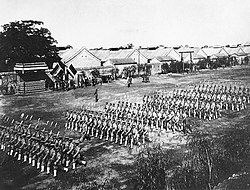

After defeating the remnants of the Ming forces, the Manchu Banner Army of approximately 200,000 strong at the time was evenly divided; half was designated the Forbidden Eight Banner Army (Chinese: 禁旅八旗; pinyin: jìnlǚ bāqí) and was stationed in Beijing. It served both as the capital's garrison and the Qing government's main strike force. The remainder of the Banner troops was distributed to guard key cities in China. These were known as the Territorial Eight Banner Army (simplified Chinese: 驻防八旗; traditional Chinese: 駐防八旗; pinyin: zhùfáng bāqí). The Manchu court, keenly aware its own minority status, reinforced a strict policy of racial segregation between the Manchus and Mongols from Han Chinese for fear of being sinicized by the latter. This policy applied directly to the Banner garrisons, most of which occupied a separate walled zone within the cities they were stationed in. In cities where there were limitation of space such as in Qingzhou, a new fortified town would be purposely erected to house the Banner garrison and their families. Beijing being the imperial seat, the regent Dorgon had the entire Chinese population forcibly relocated to the southern suburbs which became known as the "Outer Citadel" (Chinese: 外城; pinyin: wàichéng). The northern walled city called "Inner Citadel" (Chinese: 內城; pinyin: nèichéng) was portioned out to the remaining Manchu Eight Banners, each responsible for guarding a section of the Inner Citadel surrounding the Forbidden City palace complex[a]. [citation needed]

Peace and stagnation[edit]

The policy of posting Banner troops as territorial garrison was not to protect but to inspire awe in the subjugated populace at the expense of their expertise as cavalry. As a result, after a century of peace and lack of field training the Manchu Banner troops had deteriorated greatly in their combat worthiness. Secondly, before the conquest, the Manchu banner was a "citizen" army, and its members were Manchu farmers and herders obligated to provide military service to the state at times of war. The Qing government's decision to turn the banner troops into a professional force whose every welfare and need was met by state coffers brought wealth, and with it corruption, to the rank and file of the Manchu Banners and hastened its decline as a fighting force. This was mirrored by a similar decline in the Green Standard Army. During peace time, soldiering became merely a source of supplementary income. Soldiers and commanders alike neglected training in pursuit of their own economic gains. Corruption was rampant as regional unit commanders submitted pay and supply requisitions based on exaggerated head counts to the quartermaster department and pocketed the difference. When the Taiping Rebellion broke out in 1850s, the Qing court found out belatedly that the Banner and Green Standards troops could neither put down internal rebellions nor keep foreign invaders at bay. [citation needed]

Transition and modernization[edit]

Early during the Taiping Rebellion, Qing forces suffered a series of disastrous defeats culminating in the loss of the regional capital city of Nanjing in 1853. The rebels massacred the entire Manchu garrison and their families in the city and made it their capital. Shortly thereafter, a Taiping expeditionary force penetrated as far north as the suburbs of Tianjin in what was considered the imperial heartlands. In desperation the Qing court ordered a Chinese mandarin, Zeng Guofan, to organize regional (simplified Chinese: 团勇; traditional Chinese: 團勇; pinyin: tuányǒng) and village (simplified Chinese: 乡勇; traditional Chinese: 鄉勇; pinyin: xiāngyǒng) militias into a standing army called tuanlian to contain the rebellion. Zeng Guofan's strategy was to rely on local gentries to raise a new type of military organization from those provinces that the Taiping rebels directly threatened. This new force became known as the Xiang Army, named after the Hunan region where it was raised. The Xiang Army was a hybrid of local militia and a standing army. It was given professional training, but was paid for out of regional coffers and funds its commanders — mostly members of the Chinese gentry — could muster. The Xiang Army and its successor, the Huai Army, created by Zeng Guofan's colleague and student Li Hongzhang, were collectively called the "Yong Ying" (Brave Camp). [26]

Before forming and commanding the Xiang Army, Zeng Guofan had no military experience. Being a classically educated Mandarin, his blueprint for the Xiang Army was taken from a historical source — the Ming general Qi Jiguang, who, because of the weakness of regular Ming troops, had decided to form his own "private" army to repel raiding Japanese pirates in the mid-16th century. Qi Jiguang's doctrine was based on Neo-Confucian ideas of binding troops' loyalty to their immediate superiors and also to the regions in which they were raised. This initially gave the troops an excellent esprit de corps. Qi Jiguang's army was an ad hoc solution to the specific problem of combating pirates, as was Zeng Guofan's original intention for the Xiang Army, which was raise to eradicate the Taiping rebels. However, circumstances led to the Yongying system becoming a permanent institution within the Qing military, which in the long run created problems of its own for the beleaguered central government.

First, the Yongying system signaled the end of Manchu dominance in Qing military establishment. Although the Banners and Green Standard armies lingered on as parasites depleting resources, henceforth the Yongying corps became the Qing government's de facto first-line troops. Secondly the Yongying corps were financed through provincial coffers and were led by regional commanders. This devolution of power weakened the central government's grip on the whole country, a weakness further aggravated by foreign powers vying to carve up autonomous colonial territories in different parts of the Qing Empire in the later half of the 19th century. Despite these serious negative effects, the measure was deemed necessary as tax revenue from provinces occupied and threatened by rebels had ceased to reach the cash-strapped central government. Finally, the nature of Yongying command structure fostered nepotism and cronyism amongst its commanders, whom, as they ascended the bureaucratic ranks laid the seeds to Qing's eventual demise and the outbreak of regional warlordism in China during the first half of the 20th century. [27]

By the late 19th century, China was fast descending into a semi-colonial state. Even the most conservative elements within the Qing court could no longer ignore China's military weakness in contrast to the foreign "barbarians" literally beating down its gates. In 1860, during the Second Opium War, the capital Beijing was captured and the Summer Palace sacked by a relatively small Anglo-French coalition force numbering 25,000. Although the Chinese invented gunpowder, and firearms had been in continual use in Chinese warfare since as far back as the Song Dynasty, the advent of modern weaponry resulting from the European Industrial Revolution had rendered China's traditionally trained and equipped army and navy obsolete. The government attempts to modernize during the Self-Strengthening Movement were, in the view of most historians with hindsight, piecemeal and yielded few lasting results. The various reasons for the apparent failure of late-Qing modernization attempts that have been advanced including the lack of funds, lack of political will, and unwillingness to depart from tradition. These reasons remain disputed.[28]

Losing the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895 was a watershed for the Qing government. Japan, a country long regarded by the Chinese as little more than an upstart nation of pirates, had convincingly beaten its larger neighbour and in the process annihilated the Qing government's pride and joy — its modernized Beiyang Fleet, then deemed to be the strongest naval force in Asia. In doing so, Japan became the first Asian country to join the previously exclusively western ranks of colonial powers. The defeat was a rude awakening to the Qing court especially when set in the context that it occurred a mere three decades after the Meiji Restoration set a feudal Japan on course to emulate the Western nations in their economic and technological achievements. Finally, in December 1894, the Qing government took concrete steps to reform military institutions and to re-train selected units in westernized drills, tactics and weaponry. These units were collectively called the New Army. The most successful of these was the Beiyang Army under the overall supervision and control of a former Huai Army commander, General Yuan Shikai, who used his position to eventually become President of the Republic of China and finally emperor of China. [29]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Schirokauer 1978, pp. 326–327

- ^ Dennerline 2002, p. 113.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 931 ("Thirteen Offices"); Rawski 1998, p. 163 ("Thirteen Eunuch Bureaus," supervised by Manchus).

- ^ Dennerline 2002, p. 113; Oxnam 1975, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 931 (composed edicts); Oxnam 1975, p. 52.

- ^ Oxnam 1975, p. 52 (isolated emperor from his officials); Kessler 1976, p. 27.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 1016; Kessler 1976, p. 27; Oxnam 1975, p. 54.

- ^ Oxnam 1975, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Kessler 1976, p. 27; Rawski 1998, p. 163 (specific date).

- ^ Kessler 1976, p. 26; Oxnam 1975, p. 63.

- ^ Oxnam 1975, p. 65.

- ^ Oxnam 1975, p. 71 (details of membership in the Deliberative Council); Spence 2002, pp. 126–27 (other institutions).

- ^ Spence 2002, p. 133.

- ^ Kessler 1976, p. 30 (restored in 1670).

- ^ Hucker 1985, p. 531; Rawski 1988, p. 233.

- ^ Rawski 1998, p. 13.

- ^ Hucker 1998, p. 28 (staffing); Rawski 1998, pp. 12 (marriages) and 75 (births and deaths; compilation of genealogy; number of revisions).

- ^ Banner registration: Elliott 2001, p. 88. Jurisdiction: Rawksi 1998, p. 72; Rhoads 2000, p. 46. Outside the regular legal system: Wu 1970, p. 9; Lui 1990, p. 31.

- ^ a b Rawski 1998, p. 179.

- ^ Rawski 1998, pp. 179-80.

- ^ Torbert 1977.

- ^ Torbert 1977, p. 28.

- ^ Wu 1970, p. 9.

- ^ Oxnam 1975, p. 30.

- ^ a b Elliott 2001, p. 128.

- ^ Kwang-ching Liu, Richard J. Smith, "The Military Challenge: The North-west and the Coast," in John King Fairbank, Kwang-Ching Liu, Denis Crispin Twitchett, ed. (1980). Late Ch'ing, 1800-1911. Vol. Volume 11, Part 2 of The Cambridge History of China Series. Cambridge University Press. p. 202-210. ISBN 0-521-22029-7.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Liu, Smith, "The Military Challenge: The North-west and the Coast," pp.202-210.

- ^ Wakeman (1985). [page needed]

- ^ Liu, Smith, "The Military Challenge: The North-west and the Coast," pp. 251-273.

Bibliography[edit]

- Bartlett, Beatrice S. (1991), Monarchs and Ministers: The Grand Council in Mid-Ch'ing China, 1723-1820, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 0-52008645-7.

- Hucker, Charles O. (1985), A Dictionary of Official Titles in Imperial China, Stanford: Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-1193-3.

- Oxnam, Robert B. (1975), Ruling from Horseback: Manchu Politics in the Oboi Regency, 1661-1669, Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-64244-5.

- Rawski, Evelyn S. (1998), The Last Emperors: A Social History of Qing Imperial Institutions, Los Angeles and Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0674127617; 9780674127616

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help). - Torbert, Preston M. (1977), The Chʻing Imperial Household Department: A Study of Its Organization and Principal Functions, 1662-1796, Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, ISBN 0674127617; 9780674127616

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help).