User:Marian Sokolski/sandbox

The nationalization of oil supplies refers to the process of deprivatization of oil production operations, generally in the purpose of obtaining more revenue from oil; it should not be confused with restrictions on crude oil exports.

According to consulting firm PFC Energy, only 7% of the world's estimated oil and gas reserves are in countries that allow private international companies free rein. Fully 65% are in the hands of state-owned companies such as Saudi Aramco, with the rest in countries such as Russia and Venezuela, where access by Western companies is difficult. The PFC study implies political factors are limiting capacity increases in Mexico, Venezuela, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait and Russia. Saudi Arabia is also limiting capacity expansion, but because of a self-imposed cap, unlike the other countries.[1] As a result of not having access to countries amenable to oil exploration, ExxonMobil is not making nearly the investment in finding new oil that it did in 1981.[2]

On the home front, national oil companies are often torn between national expectations that they should carry the flag and their own ambitions for commercial success, which might mean a degree of emancipation from the confines of a national agenda. [3] Most oil is found in countries that have struggled for independence. Typically, governments are more likely to nationalize during times of high oil prices and weak political institutions. [4] This history sets the importance of national oil apart from any other nationalized resource.

History[edit]

The nationalization of oil supplies has been a gradual process. Before the discovery of oil, Middle Eastern countries such as Iraq, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait were all poor and underdeveloped. When oil was discovered in these developing nations during the early twentieth century, the countries did not have enough knowledge of the oil industry to make use of the newly discovered natural resources. Major oil companies saw this as an opportunity for profit and they negotiated concession agreements with the developing countries; the companies were given exclusive rights to explore and develop the production of oil within the country. [5] As a result, the world’s oil was largely in the hands of seven corporations based in the United States and Europe. [6] Five of the companies were American (Chevron, Exxon, Gulf, Mobil, and Texaco), one was British (British Petroleum), and one was Anglo-Dutch (Royal Dutch/Shell). [5] These companies have since merged into four common oil companies: Shell, ExxonMobil, Chevron, and BP. [6]

The established contracts between oil companies and nations with oil reserves gave the oil companies an advantageous position, leading to the inclusion of choice-of-law clauses. In other words, disputes over contract details would be settled by a third party instead of the host country. The only way for host countries to alter their contracts was through nationalization. Most of the countries, with the exception of Venezuela even signed away their right to tax the companies in exchange for one time royalty payments. [5]

The movement for nationalism began once the developing countries realized that the oil companies were exploiting them. Led by Venezuela, oil producing countries realized that they could control the price of oil by limiting the supply. The countries joined together as OPEC and gradually they gained control of their own oil supplies rather than allowing the oil companies to control them. [5]

Before the 1970s there were only two major incidents of successful oil nationalization--the first following the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 in Russia and the second in 1938 in Mexico. [7] Due to the swift growth of the energy economy, resources shifted to becoming nationalized to protect themselves from adjustments in demand worldwide.

OPEC Countries[edit]

Nigeria[edit]

The discovery of oil in Nigeria caused conflict within the state. The emergence of commercial oil production from the region in 1958 and thereafter raised the stakes and generated a struggle by the indigenes for control of the oil resources. [8] The northern hegemony, ruled by Hausa and Fulani, took a military dictatorship and seized control of oil production. While oil production proceeded, the region by the 1990s was one of the least developed and poorest.[8] The local communities responded with protests and successful efforts to stop oil production in the area if they did not receive any benefit. By September 1999, about 50 Shell workers had been kidnapped and released. [8] Not only are the people of Nigeria affected, but the environment in the area is also affected by deforestation and improper waste treatment.

Iran[edit]

In the late 19th century, when interest in petroleum as an industrial grade fuel first emerged, Iran under the Qajar dynasty was in economic and political disarray. [9] Iran, now among the world's leading crude-oil exporters, could become a net importer of oil within the next decade due to rising demand and slow-growing production.[10] Possessing the world's second-biggest proven reserves of oil, it infuriated its people when the government brought in petrol rationing on two hours notice.[11] Due to limited refinery capacity, it has discouraged gasoline usage. Shortly after the petrol/gasoline rationing, which has reduced demand in some areas by 20%-30%, it announced it will not be producing cars powered only by gasoline.[12]

Venezuela[edit]

In 1958 a revolution in Venezuela brought an end to their military dictatorship.[5] The newly elected Minister of Mines and Hyrdocarbons, Perez Alfonzo, acted to raise the income tax on oil companies and introduced the key aspect of supply and demand to the oil trade. Major oil companies operating in Venezuela have had difficulty with the spreading resource nationalism. Exxon Mobil and ConocoPhilips have said they would walk away from their large investment in the Orinoco heavy-oil belt rather than accept tough new contract terms which raise taxes and oblige all foreign companies to accept minority shares in joint ventures with the state oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA).[13]

Non OPEC Countries[edit]

Latin America[edit]

Enrique Mosconi, the director of the Argentine state owned oil company Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales (YPF, the first state owned oil company in the world), advocated oil nationalization in the late 1920s among Latin American countries.

Mexico[edit]

Mexico nationalized its oil industry in 1938, and has never privatized, restricting foreign investment. Since the giant Cantarell field in Mexico is now in decline, the state oil company Pemex has faced intense political opposition to opening up the country's oil and gas sector to foreign participation. Some feel that the state oil company Pemex does not have the capacity to develop deep water assets by itself, but needs to do so if it is to stem the decline in the country's crude production.[14]

Canada[edit]

Canada reigns as the United States' leading oil supplier, exporting some 707,316,000 barrels of oil per year (1.938.00 barrels per day), 99 percent of its annual oil exports, according to the EIA. [15]

Russia[edit]

In Russia, Vladimir Putin's government has pressured Royal Dutch Shell to hand over control of one major project on Sakhalin Island, to Russia's Gazprom in December. The founder of formerly private Yukos has also been jailed, and the company absorbed by state-owned Rosneft.[16] Such moves strain the confidence of international oil companies in forming partnerships with Russia.[10]

Economics and Politics[edit]

The nationalization of oil supplies is a significant turning point in the process of oil policy-making in oil producing countries. Nationalization eliminated the concession system and allowed OPEC countries to recover direct control over their resources. Once these countries became the sole owners of their resources, they had to decide how to maximize the net present value of their known stock of oil in the ground. [17]

Due to the overall instability of supply, oil became an instrument of foreign policy for oil-exporting countries. [7]

Nationalization increased the stability in the oil markets and broke the vertical integration within the system. Vertical integration was replaced with a dual system where OPEC countries control the production and marketing of crude oil while oil companies control the transportation, refining, distribution, and sale of oil products. [17]

High oil prices raise the bargaining power of oil-producing countries. As a result, these countries are more likely to nationalize their oil supplies during times of high oil prices. However, nationalization can come with various costs and it is often questioned why a government would respond to an oil price increase with nationalization rather than by imposing higher taxes. Contract theory provides reasoning against nationalization. [4]

See also[edit]

- Energy security

- Energy security and renewable technology

- Petroleum

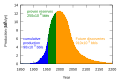

- Peak oil

- U.S. Energy Independence

References[edit]

- ^ Sheila McNulty (2007-05-09). "Politics of oil seen as threat to supplies". Financial Times.

- ^ Justin Fox (2007-05-31). "No More Gushers for ExxonMobil". Time magazine.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Valérie Marcel (2006). "Oil Titans: National Oil Companies in the Middle East". Brookings Institution Press.

- ^ a b Sergei Guriev, Anton Kolotilin and Konstantin Sonin (2009-06-23). "Determinants of Nationalization in the Oil Sector: A Theory and Evidence from Panel Data". Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b c d e Adam Bird and Malcolm Brown (2005-06-02). "The History and Social Consequences of a Nationalized Oil Industry".

- ^ a b Antonia Juhasz (2007-03-13). "Whose Oil Is It, Anyway?". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Edward L. Morse (1999). "A New Political Economy of Oil?" (PDF). The Trustees of Columbia University.

- ^ a b c Augustine Ikelegbe (2005). "The Economy of Conflict in the Oil Rich Niger Delta Region of Nigeria" (PDF).

- ^ National Iranian Oil Company

- ^ a b Mark Trumbull (2007-04-03). "Risks of rising oil nationalism". Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ Mark Colvin and Sabra Lane (2007-06-28). "Iran's oil restrictions 'a warning for Australia'". Energy Bulletin.

- ^ "Iran ends petrol-only car making". BBC. 2007-06-07.

- ^ "It's our oil". The Economist. 2007-06-28.

- ^ Ross McCracken (2007). "IOCs, NOCs Facing Off Over Scarcer Resources". Platts.

- ^ Editors (2010-07-28). "The Top Seven Suppliers of Oil to the US". Global Post.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Country Profile: Russia". BBC. 2007-09-17.

- ^ a b Antoine Ayoub (1994-05-09). "Oil: Economics and Political".