User:Orser67/Buchanan

Presidential election of 1856[edit]

During the Pierce administration, Buchanan served as the United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom. Buchanan's service abroad conveniently placed him outside of the country while the debate over the Kansas-Nebraska Act roiled the nation.[1] While Buchanan did not overtly seek the presidency, he most deliberately chose not to discourage the movement on his behalf, something that was well within his power on many occasions.[2] The 1856 Democratic National Convention met in June 1856, writing a platform that largely reflected Buchanan's views, including support for the Fugitive Slave Law, an end to anti-slavery agitation, and U.S. "ascendancy in the Gulf of Mexico." President Pierce hoped for re-nomination, while Senator Stephen A. Douglas also loomed as a strong candidate. Buchanan led on the first ballot, boosted by the support of powerful Senators John Slidell, Jesse Bright, and Thomas F. Bayard, who presented Buchanan as an experienced leader who could appeal to the North and South. Buchanan won the nomination after seventeen ballots, and was joined on the ticket by John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky.[3]

Buchanan faced not just one but two candidates in the general election: former Whig President Millard Fillmore ran as the American Party (or "Know-Nothing") candidate, while John C. Frémont ran as the Republican nominee. Sticking with the convention of the times, Buchanan did not himself campaign, but he wrote letters and pledged to uphold the Democratic platform. In the election, Buchanan carried every slave state except for Maryland, as well as five free states, including his home state of Pennsylvania. He won 45 percent of the popular vote and, most importantly, won the electoral vote, taking 174 electoral votes compared to Frémont's 114 electoral votes and Fillmore's 8 electoral votes. Buchanan's election made him the first and so far only president from Pennsylvania. In his victory speech, Buchanan denounced Republicans, calling the the Republican Party a "dangerous" and "geopraphical" party that had unfairly attacked the South.[4] President-elect Buchanan would also state, "the object of my administration will be to destroy sectional party, North or South, and to restore harmony to the Union under a national and conservative government."[5] He set about this initially by maintaining a sectional balance in his appointments and persuading the people to accept constitutional law as the Supreme Court interpreted it. The court was considering the legality of restricting slavery in the territories and two justices had hinted to Buchanan their findings.[6]

Personnel[edit]

Cabinet and administration[edit]

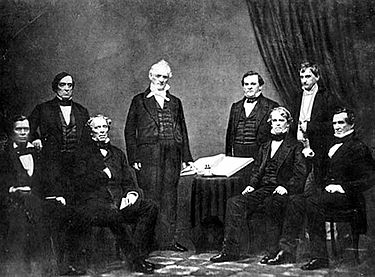

| The Buchanan cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | James Buchanan | 1857–1861 |

| Vice President | John C. Breckinridge | 1857–1861 |

| Secretary of State | Lewis Cass | 1857–1860 |

| Jeremiah S. Black | 1860–1861 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Howell Cobb | 1857–1860 |

| Philip Francis Thomas | 1860–1861 | |

| John Adams Dix | 1861 | |

| Secretary of War | John B. Floyd | 1857–1860 |

| Joseph Holt | 1860–1861 | |

| Attorney General | Jeremiah S. Black | 1857–1860 |

| Edwin M. Stanton | 1860–1861 | |

| Postmaster General | Aaron V. Brown | 1857–1859 |

| Joseph Holt | 1859–1860 | |

| Horatio King | 1861 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Isaac Toucey | 1857–1861 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Jacob Thompson | 1857–1861 |

From left to right: Jacob Thompson, Lewis Cass, John B. Floyd, James Buchanan, Howell Cobb, Isaac Toucey, Joseph Holt and Jeremiah S. Black, (c. 1859)

As his inauguration approached, Buchanan sought to establish a harmonious cabinet, as he hoped to avoid the in-fighting that had plagued Andrew Jackson's cabinet. Buchanan chose four southerners and three northerners, the latter of whom were all considered to be doughfaces. Buchanan sought to be the clear leader of the cabinet, and chose men who would agree with his views. Anticipating that his administration would concentrate on foreign policy and that Buchanan himself would largely direct foreign policy, he appointed the aging Lewis Cass as Secretary of State. Buchanan's appointment of southerners and southern sympathizers alienated many in the north, and his failure to appoint any followers of Stephen Douglas divided the party.[7]

Judicial appointments[edit]

Buchanan appointed one Justice to the Supreme Court of the United States, Nathan Clifford. Buchanan appointed only seven other Article III federal judges, all to United States district courts. He also appointed two Article I judges to the United States Court of Claims.

Dred Scott case[edit]

In his inaugural address, besides promising not to run again, Buchanan referred to the territorial question as "happily, a matter of but little practical importance" since the Supreme Court was about to settle it "speedily and finally", and proclaimed that when the decision came, he would "cheerfully submit, whatever this may be". Two days later, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney delivered the Dred Scott decision, asserting that Congress had no constitutional power to exclude slavery in the territories. Such comments delighted Southerners and incited anger in the North.[8]

Buchanan preferred to see the territorial question resolved by the Supreme Court. He had written to Justice John Catron in January 1857, inquiring about the outcome of the case and suggesting that a broader decision would be more prudent.[9] Catron, who was from Tennessee, replied on February 10 that the Supreme Court's southern majority would decide against Scott, but would likely have to publish the decision on narrow grounds if there was no support from the Court's northern justices—unless Buchanan could convince his fellow Pennsylvanian, Justice Robert Cooper Grier, to join the majority.[10][11] Buchanan then wrote to Grier and successfully prevailed upon him, allowing the majority leverage to issue a broad-ranging decision that transcended the specific circumstances of Scott's case to declare the Missouri Compromise of 1820 unconstitutional.[12][13] The correspondence was not public at the time; however, at his inauguration, Buchanan was seen in whispered conversation with Chief Justice Roger B. Taney. When the decision was issued two days later, Republicans began spreading word that Taney had revealed to Buchanan the forthcoming result.[13] Abraham Lincoln, in his 1858 House Divided Speech, denounced Buchanan, Taney, Stephen A. Douglas and Franklin Pierce as accomplices of the Slave Power, a reference to the disproportionate power wielded by Southern whites.[14]

Chaos in Kansas; Buchanan breaks with Douglas[edit]

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 created Kansas Territory, and allowed the settlers there to choose whether to allow slavery. This resulted in violence between "Free-Soil" (antislavery) and proslavery settlers in what became known as the "Bleeding Kansas" crisis. The antislavery settlers organized a government in Topeka, while proslavery settlers established a seat of government in Lecompton, Kansas. For Kansas to be admitted to statehood, a state constitution had to be submitted to Congress with the approval of a majority of residents.

Toward this end, Buchanan appointed Robert J. Walker to replace John W. Geary as territorial governor, with the mission of reconciling the settler factions and approving a constitution, in May 1857. Walker, who was from Mississippi, was expected to assist the proslavery faction in gaining approval of their Lecompton Constitution. However, most Kansas settlers were Free-Soilers. The Lecomptonites held a referendum, which Free-Soilers boycotted, with trick terms and claimed their constitution was adopted. Walker resigned in disgust.[15]

Nevertheless, Buchanan now pushed for congressional approval of Kansas statehood under the Lecompton Constitution. Buchanan made every effort to secure congressional approval, offering favors, patronage appointments, and even cash for votes.[16] The Lecompton bill passed through the House of Representatives, but failed in the Senate, where it was opposed by Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, leader of the northern Democrats. Douglas advocated "popular sovereignty" (letting settlers decide on slavery—nicknamed "squatter sovereignty" by Douglas' opponents); he rejected the fraudulent way the Lecompton Constitution was supposedly adopted.[17]

The battle over Kansas escalated into a battle for control of the Democratic Party. On one side were Buchanan, most Southern Democrats, and northern Democrats allied to the Southerners ("Doughfaces"); on the other side were Douglas and most northern Democrats plus a few Southerners. The struggle lasted from 1857 to 1860. Buchanan used his patronage powers to remove Douglas' sympathizers in Illinois and Washington, DC and installed proadministration Democrats, including postmasters.[18]

Douglas's Senate term ended in 1859, so the Illinois legislature elected in 1858 had to choose whether to re-elect him. The Senate choice was the primary issue of the legislative election, marked by the famous Lincoln-Douglas debates. Buchanan, working through Federal patronage appointees in Illinois, ran candidates for the legislature in competition with both the Republicans and the Douglas Democrats. This could easily have thrown the election to the Republicans—which showed the depth of Buchanan's animosity toward Douglas.[19] In the end, however, Douglas Democrats won the legislative election and Douglas was re-elected to the Senate. Douglas forces took control throughout the North, except in Buchanan's home state of Pennsylvania. Buchanan was reduced to a narrow base of southern supporters.[15][20]

Panic of 1857[edit]

The Panic of 1857 began in the summer of that year, brought on mostly by the people's overconsumption of goods from Europe to such an extent that the Union's specie was drained off, overbuilding by competing railroads, and rampant land speculation in the west. Most of the state banks had overextended credit, to more than $7.00 for each dollar of gold or silver. The Republicans considered the Congress to be the culprit for having recently reduced tariffs.

Buchanan's response, outlined in his first Annual Message to Congress, was "reform not relief". While the government was "without the power to extend relief",[21] it would continue to pay its debts in specie, and while it would not curtail public works, none would be added. He urged the states to restrict the banks to a credit level of $3 to $1 of specie, and discouraged the use of federal or state bonds as security for bank note issues. The economy did eventually recover, though many Americans suffered as a result of the panic.[22] The South, due to an agriculture-based economy, was considered to have been less severely affected than the North, where manufacturers were hit hardest. Buchanan, by the time he left office in 1861, had accumulated a federal deficit of $17 million.[21]

Utah War[edit]

In March 1857, Buchanan received conflicting reports from federal judges in the Utah Territory that their offices had been disrupted and they had been driven from their posts by the Mormons. He knew that the Pierce administration had refused to facilitate Utah being granted statehood and the Mormons feared the loss of their property rights. Accepting the wildest rumors and believing the Mormons to be in open rebellion against the United States, Buchanan sent the Army in November of that year to replace Brigham Young as governor with the non-Mormon Alfred Cumming. While the Mormons' defiance of federal authority in the past had become traditional, some question whether Buchanan's action was a justifiable or prudent response to uncorroborated reports.[8] Complicating matters, Young's notice of his replacement was not delivered because the Pierce administration had annulled the Utah mail contract.[8] After Young reacted to the military action by mustering a two-week expedition destroying wagon trains, oxen, and other Army property, Buchanan dispatched Thomas L. Kane as a private agent to negotiate peace. The mission succeeded, the new governor was shortly placed in office, and the Utah War ended. The President granted amnesty to all inhabitants who would respect the authority of the government, and moved the federal troops to a nonthreatening distance for the balance of his administration.[23]

Partisan deadlock[edit]

The division between northern and southern Democrats allowed the Republicans to win a plurality in the House in the election of 1858. Their control of the chamber allowed the Republicans to block most of Buchanan's agenda (including his proposals for expansion of influence in Central America, and for the purchase of Cuba). Buchanan thought the ideologies of the United States would bring peace and prosperity to these neighboring lands as they had in the Northwest and that without U.S. influence, the major European powers would intervene. The imperative of safe and speedy travel from east to west was of strategic importance to the country. These goals would not be reached. Buchanan, in turn, vetoed six substantial pieces of Republican legislation, causing further hostility between Congress and the White House.[24]

Covode committee[edit]

In March 1860, the House created the Covode Committee to investigate the administration for evidence of offenses, some impeachable, such as bribery and extortion of representatives in exchange for their votes. The committee, with three Republicans and two Democrats, was accused by Buchanan's supporters of being nakedly partisan; they also charged its chairman, Republican Rep. John Covode, with acting on a personal grudge (since the president had vetoed a bill that was fashioned as a land grant for new agricultural colleges, but was designed to benefit Covode's railroad company[25]). However, the Democratic committee members, as well as Democratic witnesses, were equally enthusiastic in their pursuit of Buchanan, and as pointed in their condemnations, as the Republicans.[26][27]

The committee was unable to establish grounds for impeaching Buchanan; however, the majority report issued on June 17 exposed corruption and abuse of power among members of his cabinet, as well as allegations (if not impeachable evidence) from the Republican members of the Committee, that Buchanan had attempted to bribe members of Congress in connection with the Lecompton constitution. (The Democratic report, issued separately the same day, pointed out that evidence was scarce, but did not refute the allegations; one of the Democratic members, Rep. James Robinson, stated publicly that he agreed with the Republican report even though he did not sign it.[27])

Buchanan claimed to have "passed triumphantly through this ordeal" with complete vindication. Nonetheless, Republican operatives distributed thousands of copies of the Covode Committee report throughout the nation as campaign material in that year's presidential election.[28][29]

Disintegration: Election of 1860[edit]

Sectional strife rose to such a pitch that the Democratic Party's national convention in 1860 led directly to a schism in the Party. Buchanan played little part at the national convention, meeting in Charleston, South Carolina. The southern wing walked out of the convention and nominated its own candidate for the presidency, incumbent Vice President John C. Breckinridge. Another faction nominated former Speaker of the House John Bell, who took no position on slavery; his only focus was on saving the Union. The remainder of the party finally nominated Buchanan's archenemy, Stephen Douglas. For his part, President Buchanan supported Breckinridge's candidacy. When the Republicans nominated Abraham Lincoln, it was a near certainty that he would be elected.

As early as October, the army's Commanding General, Winfield Scott, warned Buchanan that Lincoln's election would likely cause at least seven states to secede. He also recommended to Buchanan that massive amounts of federal troops and artillery be deployed to those states to protect federal property, although he also warned that few reinforcements were available (Congress had since 1857 failed to heed both men's calls for a stronger militia and had allowed the Army to fall into deplorable condition.[30]) Buchanan, however, distrusted Scott (the two had long been political adversaries) and ignored his recommendations.[31] After Lincoln's election, Buchanan directed War Secretary Floyd to reinforce southern forts with such provisions, arms and men as were available; however, Floyd convinced him to revoke the order.[30]

With Lincoln's victory, talk of secession and disunion reached a boiling point. Buchanan was forced to address it in his final message to Congress. Both factions awaited news of how Buchanan would deal with the question. In his message,[32] Buchanan denied the legal right of states to secede but held that the federal government legally could not prevent them. He placed the blame for the crisis solely on "intemperate interference of the Northern people with the question of slavery in the Southern States", and suggested that if they did not "repeal their unconstitutional and obnoxious enactments ... the injured States, after having first used all peaceful and constitutional means to obtain redress, would be justified in revolutionary resistance to the Government of the Union."[33] Buchanan's only suggestion to solve the crisis was "an explanatory amendment" reaffirming the constitutionality of slavery in the states, the fugitive slave laws, and popular sovereignty in the territories.[33] His address was sharply criticized both by the north, for its refusal to stop secession, and the south, for denying its right to secede.[34] Five days after the address was delivered, Treasury Secretary Howell Cobb resigned, feeling that his views and the President's had become irreconcilable.[35]

Efforts were made by statesmen such as Sen. John J. Crittenden, Rep. Thomas Corwin, and former president John Tyler to negotiate a compromise to stop secession, with Buchanan's support; all failed. Failed efforts to compromise were also made by a group of governors meeting in New York. Buchanan employed a last-minute tactic, in secret, to bring a solution. He attempted in vain to procure President-elect Lincoln's call for a constitutional convention or national referendum to resolve the issue of slavery. Lincoln declined.[36]

South Carolina declared its secession on December 20, 1860, followed by six other slave states, and, by February 1861, they had formed the Confederate States of America. As Scott had surmised, the secessionist governments declared eminent domain over federal property within their states; Buchanan and his administration took no action to stop the confiscation of government property.

Beginning in late December, Buchanan reorganized his cabinet, ousting Confederate sympathizers and replacing them with hard-line nationalists Jeremiah S. Black, Edwin M. Stanton, Joseph Holt and John A. Dix. These conservative Democrats strongly believed in American nationalism and refused to countenance secession. At one point, Treasury Secretary Dix ordered Treasury agents in New Orleans, "If any man pulls down the American flag, shoot him on the spot." The new cabinet advised Buchanan to request from Congress the authority to call up militias and give himself emergency military powers, and this he did, on January 8, 1861. Nevertheless, by that time Buchanan's relations with Congress were so strained that his requests were rejected out of hand. Many consider him as the worst President in history for his failure to prevent the American Civil War.[37][38][39][40]

Fort Sumter[edit]

Before Buchanan left office, all arsenals and forts in the seceding states were lost (except Fort Sumter, off the coast of Charleston, South Carolina, and three island outposts in Florida), and a fourth of all federal soldiers surrendered to the Texas militia. Knowing that secessionist fervor was strongest in South Carolina, Buchanan made a quiet pact with South Carolina's legislators that he would not reinforce the Charleston garrison in exchange for no interference from the state.[41] However, Buchanan did not inform the Charleston commander, Major Robert Anderson, of the agreement, and on December 26 Anderson violated it by moving his command to Fort Sumter. Southerners responded with a demand that Buchanan remove Anderson, while northerners demanded support for the commander. On December 31, in an apparent panic and without consulting Anderson, Buchanan ordered reinforcements.[41]

On January 5, Buchanan sent civilian steamer Star of the West to carry reinforcements and supplies to Fort Sumter, which, located in Charleston harbor, was a conspicuously visible spot in the Confederacy. On January 9, 1861, South Carolina state batteries opened fire on the ship, causing it to withdraw and return to New York. Buchanan was again criticized by both north (for lack of retaliation against the hostile South Carolina batteries) and south (for attempting to reinforce Fort Sumter), further alienating both factions.[41][42] Paralyzed, Buchanan made no further moves either to prepare for war or to avert it.

On Buchanan's final day as president, March 4, 1861, he remarked to the incoming Lincoln, "If you are as happy in entering the White House as I shall feel on returning to Wheatland, you are a happy man."[43]

States admitted to the Union[edit]

Three new states were admitted to the Union while Buchanan was in office:

Legacy[edit]

The day before his death, Buchanan predicted that "history will vindicate my memory".[47] Historians have defied that prediction and criticize Buchanan for his unwillingness or inability to act in the face of secession. Historical rankings of United States Presidents, considering presidential achievements, leadership qualities, failures and faults, consistently place Buchanan among the least successful presidents.[48][49] When scholars are surveyed he ranks close to the bottom in terms of vision/agenda-setting, domestic leadership, foreign policy leadership, moral authority and positive historical significance of their legacy.[50]

Buchanan biographer Philip Klein explains the challenges Buchanan faced:

Buchanan assumed leadership ... when an unprecedented wave of angry passion was sweeping over the nation. That he held the hostile sections in check during these revolutionary times was in itself a remarkable achievement. His weaknesses in the stormy years of his presidency were magnified by enraged partisans of the North and South. His many talents, which in a quieter era might have gained for him a place among the great presidents, were quickly overshadowed by the cataclysmic events of civil war and by the towering Abraham Lincoln."[51]

References[edit]

- ^ Baker 2004, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Klein 1962, pp. 248–252.

- ^ Baker 2004, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Baker 2004, pp. 70–73.

- ^ Klein 1962, pp. 261–262.

- ^ Chadwick 2008, p. 48.

- ^ Baker 2004, pp. 77–80.

- ^ a b c Klein 1962, p. 316.

- ^ Klein 1962, pp. 271–272.

- ^ Hall 2001, p. 566.

- ^ Baker 2004, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Armitage et al. 2005, p. 388.

- ^ a b Baker 2004, p. 85.

- ^ "A House Divided (final paragraph)". Bureau of International Information Programs (IIP), U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 2013-12-22.

- ^ a b Potter 1976, pp. 297–327.

- ^ Baker 2004, p. 103.

- ^ Chadwick 2008, p. 17.

- ^ Chadwick 2008, p. 91.

- ^ Chadwick 2008, p. 117.

- ^ Klein 1962, pp. 286–299.

- ^ a b Baker 2004, p. 90.

- ^ Klein 1962, pp. 314–315.

- ^ Klein 1962, p. 317.

- ^ Klein 1962, p. 312.

- ^ Klein 1962, p. 338.

- ^ Klein 1962, pp. 338–9.

- ^ a b Grossman 2003, p. 78.

- ^ Baker 2004, pp. 114–118.

- ^ Klein 1962, p. 339.

- ^ a b Klein 1962, pp. 356–358.

- ^ Baker 2004, pp. 76, 133.

- ^ "James Buchanan, Fourth Annual Message to Congress on the State of the Union, December 3, 1860". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved 2012-04-28.

- ^ a b Buchanan (1860)

- ^ Klein 1962, p. 363.

- ^ "The Resignation of Secretary Cobb. The Correspondence". The New York Times. December 14, 1860.

- ^ Klein 1962, pp. 381–387.

- ^ Silver, Nate (23 January 2013). "Contemplating Obama's Place in History, Statistically". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ^ Lind, Michael (3 December 2006). "He's Only Fifth Worst". The Washington Post. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ^ Geoghegan, Tom (1 July 2013). "James Buchanan: Worst US president?". BBC News, Washington. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ^ Dunbar, Elizabeth (19 February 2006). "James Buchanan worst president, scholars say". Pocono News. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ^ a b c "James Buchanan's Activist Blunder". The New York Times. January 5, 2011.

- ^ "James Buchanan – Fort sumter". Profiles of U. S. Presidents. Retrieved 2012-04-28.

- ^ Baker 2004, p. 140.

- ^ "Today in History: May 11". loc.gov. Library of Congress.

- ^ "Oregon". A+E Networks Corp. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ "Today in History: January 29". loc.gov. Library of Congress.

- ^ "Buchanan's Birthplace State Park". Pennsylvania State Parks. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved 2009-03-28.

- ^ Tolson, Jay (February 16, 2007). "The 10 Worst Presidents". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ^ Hines, Nico (October 28, 2008). "The 10 worst presidents to have held office". The Times. London. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ^ "The top US presidents: First poll of UK experts". BBC News. January 17, 2011.

- ^ Klein 1962, p. 429.

Bibliography[edit]

- Baker, Jean H. (2004). James Buchanan. New York: Times Books. ISBN 0-8050-6946-1. excerpt and text search

- Curtis, George Ticknor (1883). Life of James Buchanan: Fifteenth President of the United States. Vol. 2. Harper & Brothers. [1] [2]

- Klein, Philip S. (1962). President James Buchanan: A Biography (1995 ed.). Newtown, Connecticut: American Political Biography Press. ISBN 0-945707-11-8.

- Nevins, Allan (1950). The Emergence of Lincoln: Douglas, Buchanan, and Party Chaos, 1857–1859. New York: Scribner. ISBN 9780684104157.

- Potter, David Morris (1976). The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 9780060905248. Pulitzer prize.

- Rhodes, James Ford (1906). History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the End of the Roosevelt Administration. Vol. 2. Macmillan.

- Stampp, Kenneth M. (1990). America in 1857: A Nation on the Brink. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195074819.

- Watson, Robert P. (2012). Affairs of State: The Untold History of Presidential Love, Sex, and Scandal, 1789–1900. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 9781442218369.

- McPherson, James M. (1988). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199743902.

- Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (2009). The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History: A Political, Social, and Military History. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851099528.

- Chadwick, Bruce (2008). 1858: Abraham Lincoln, Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, Ulysses S. Grant and the War They Failed to See. Sourcebooks, Inc. ISBN 978-1402209413.

- Hall, Timothy L. (2001). Supreme Court justices: a biographical dictionary. New York, NY: Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8153-1176-8.

- Armitage, Susan H.; Faragher, John Mack; Buhle, Mari Jo; Czitrom, Daniel J. (2005). Out of Many, TLC Combined, Revised Printing (4th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-195130-0.

- Grossman, Mark (2003). Political Corruption in America: An Encyclopedia of Scandals, Power, and Greed. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-57607-060-3.

- Ross, Shelley (1988). Fall from Grace: Sex, Scandal, and Corruption in American Politics from 1702 to the Present. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-35381-8.

- Beatty, Michael A. (2001). County Name Origins of the United States. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-1025-6.

- Klein, Philip Shriver (December 1955). "The Lost Love of a Bachelor President". American Heritage Magazine. 7 (1). Retrieved 2012-11-29.

Primary sources

- Buchanan, James. Fourth Annual Message to Congress. (1860, December 3).

- Buchanan, James. Mr Buchanan's Administration on the Eve of the Rebellion (1866)

- National Intelligencer (1859)

Further reading[edit]

- Binder, Frederick Moore. "James Buchanan: Jacksonian Expansionist" Historian 1992 55(1): 69–84. ISSN 0018-2370 Full text: in Ebsco

- Binder, Frederick Moore. James Buchanan and the American Empire. Susquehanna U. Press, 1994.

- Birkner, Michael J., ed. James Buchanan and the Political Crisis of the 1850s. Susquehanna U. Press, 1996.

- Boulard, Garry. The Worst President--The Story of James Buchanan iUniverse, 2015. ISBN 978-1-4917-5961-5.

- Meerse, David. "Buchanan, the Patronage, and the Lecompton Constitution: a Case Study" Civil War History 1995 41(4): 291–312. ISSN 0009-8078

- Nevins, Allan. The Emergence of Lincoln 2 vols. (1960) highly detailed narrative of his presidency

- Nichols, Roy Franklin; The Democratic Machine, 1850–1854 (1923), detailed narrative; online

- Quist, John W. and Birkner, Michael J. (eds.), james Buchanan and the Coming of the Civil War. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2013.

- Rhodes, James Ford History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the McKinley-Bryan Campaign of 1896 vol 2. (1892)

- Silbey, Joel H. (2014). A Companion to the Antebellum Presidents 1837–1861. Wiley. ISBN 9781118609293. pp 397–464

- Smith, Elbert B. The Presidency of James Buchanan (1975). ISBN 0-7006-0132-5, standard history of his administration

- Updike, John Buchanan Dying: A Play (1974). ISBN 0-394-49042-8, ISBN 0-8117-0238-3, containing an 80-page historical "Afterword" that discusses sources, etc.

External links[edit]

- United States Congress. "Orser67/Buchanan (id: B001005)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- James Buchanan: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- Biography of James Buchanan (Official White House site)

- The James Buchanan papers, spanning the entirety of his legal, political and diplomatic career, are available for research use at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

- University of Virginia article: Buchanan biography

- James Buchanan at Tulane University

- Essay on James Buchanan and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady from the Miller Center of Public Affairs

- "Life Portrait of James Buchanan", from C-SPAN's American Presidents: Life Portraits, June 21, 1999

Primary sources

- Works by James Buchanan at Project Gutenberg

- Error in Template:Internet Archive author: Orser67/Buchanan doesn't exist.

- James Buchanan Ill with Dysentery Before Inauguration: Original Letters Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- Mr. Buchanans Administration on the Eve of the Rebellion. President Buchanans memoirs.

- Inaugural Address

- Fourth Annual Message to Congress, December 3, 1860