User:Penitentes/Dixie Fire - Overhaul

| This is not a Wikipedia article: It is an individual user's work-in-progress page, and may be incomplete and/or unreliable. For guidance on developing this draft, see Wikipedia:So you made a userspace draft. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL |

| Dixie Fire | |

|---|---|

Multiple smoke plumes rise from the Dixie Fire, as captured by an astronaut's camera from the International Space Station on August 4, 2021. | |

| Date(s) | July 13, 2021 — October 25, 2021 |

| Location | Northern California |

| Coordinates | 39°49′08″N 121°25′08″W / 39.819°N 121.419°W |

| Statistics | |

| Burned area | 963,309 acres 1,505 square miles 3,898 square kilometres 389,837 hectares[1] |

| Impacts | |

| Deaths | 3 (firefighter) |

| Non-fatal injuries | 3 firefighters |

| Structures destroyed | 1,329 destroyed and 95 damaged[2] |

| Damage | $1.15 billion USD (minimum estimate) [3] |

| Ignition | |

| Cause | Tree contacting electrical distribution lines[2] |

| Perpetrator(s) | Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) |

| Motive | Cause determined, federal prosecutors continue to determine whether PG&E bears criminal responsibility[4] |

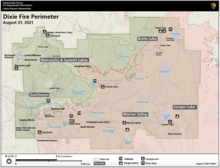

| Map | |

The 2021 Dixie Fire was an enormous, devastating wildfire that became the single largest (non-complex) fire in California's recorded history, burning 963,309 acres—at more than 1,500 square miles, an area larger than the state of Rhode Island. After starting on July 13, 2021, the fire burned through large parts of Butte, Plumas, Lassen, Shasta, and Tehama counties in the northern Sierra Nevada over the course of nearly 3 months, before finally being declared 100% contained on October 25, 2021.[5] The effort to stop the Dixie Fire was one of the largest and most expensive wildfire suppression efforts in United States history, costing more than $637 million and involving more than 6,500 firefighters simultaneously at the height of the firefight.

The Dixie Fire heavily damaged or destroyed multiple communities, including Warner Valley, Canyondam, ___, and most notably Greenville. It ultimately destroyed ___ structures, and damaged ____ more. While the Dixie Fire caused no civilian fatalities, one firefighter died from complications after contracting COVID-19 during the suppression effort.

The fire was caused by a tree falling on a PG&E power line in the Feather River Canyon, an incident which became the subject of a Cal Fire investigation that ultimately found PG&E responsible...

The Dixie Fire was the largest and most destructive wildfire of California's 2021 wildfire season, which was the state's second-largest wildfire season ever recorded. During it, the Dixie Fire became the first fire known to burn from one side of the Sierra Nevada to the other, igniting in the foothills in the Feather River Canyon near Concow on July 13 and reaching Highway 395 in mid-August. Just weeks later, the Caldor Fire repeated the feat when it burned from the Sierra foothills near Omo Ranch all the way to the Lake Tahoe basin, threatening but ultimately sparing the community of South Lake Tahoe. Other notable wildfires in California in 2021 included the small but destructive Fawn Fire and River Fire and the Beckwourth Complex fires, which the Dixie Fire ultimately burned all the way to on its southern end.

---

The enormous and destructive 2021 Dixie Fire was the largest single wildfire in the history of the state of California. Ignited by a tree falling on a PG&E power line on July 13, 2021, the fire burned through large parts of Butte, Plumas, Lassen, Shasta, and Tehama counties over the course of nearly 3 months before finally being declared 100% contained on October 25, 2021.[5]

The effort to stop the wildfire was one of the largest and most expensive such firefights in United States history. More than x FFs, y $$

It was named after Dixie Road, near where the fire started in Butte County.[6] The fire began in the Feather River Canyon near Cresta Dam on July 13, 2021, and burned 963,309 acres (389,837 ha) before being 100% contained on October 25, 2021.[7] It was the largest single (i.e. non-complex) wildfire in recorded California history, and the second-largest wildfire overall (after the August Complex fire of 2020).[8][9] The fire damaged or destroyed several small towns or communities, including Greenville on August 4, Canyondam on August 5, and Warner Valley on August 12.[10]

By July 23, it had become the largest wildfire of the 2021 California fire season; by August 6, it had grown to become the largest single (i.e. non-complex) wildfire in the state's history, burning an area larger than the state of Rhode Island.[11][12] It was the first fire known to have burned across the crest of the Sierra Nevada (followed by the Caldor Fire later in the season).[13][14] Smoke from the Dixie Fire caused unhealthy air quality across the Western United States,[15] including states as far east as Utah and Colorado.[16][17][18] The Dixie Fire was the most expensive wildfire in United States history, costing $637.4 million to fight (this figure does not include damage or insurance claims, only suppression costs).[19]

Timeline[edit]

Contributing factors[edit]

A number of background factors contributed to the size and intensity of the Dixie Fire. 2021 was the hottest summer ever recorded in California.[20] That year also saw further intensification of what scientists have found to be the most extreme megadrought in at least 1,200 years in the Western/Southwestern United States, amplified by high temperatures, low precipitation, and anthropogenic climate change[21]: during the 2021 water year ( the period between October 1, 2020, and September 30, 2021), Northern California received less than half of its usual precipitation.[22][23] The Sierra snowpack, measured during its typical peak on April 1, was just 59% of the historical average, and runoff just 20% of the amount forecast.[21] Reservoirs in the state shrunk, and vegetation dried out to the point where both living and dead conifers were drier than kiln-dried lumber.[24]

Rigorous fire suppression policies in the United States also meant that much of the area burned by the Dixie Fire had little fire history, going back more than 40 years.[25] The resulting overcrowded forests became more vulnerable to drought, as well as bark beetle infestations that were the primary cause of death for more than 163 million trees in California between 2010 and 2019.[26] Bark beetle-affected forests (especially species common in the Sierra Nevada such as the lodgepole pine) are chemically altered, rendering them more flammable and subject to intense crown fires.[27]

Ignition[edit]

The Dixie Fire began beneath a Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) 12-kilovolt power distribution line, located on the south-facing northern slope of the Feather River Canyon in a remote area above Highway 70 and Cresta Dam, midway between Paradise and Belden.[28] Transmission lines, also operated by PG&E, further down the canyon were the cause of the devastating and fatal Camp Fire in 2018.

At approximately 6:48 AM, a 65-foot tall Douglas fir, 65 feet tall and 16 inches in diameter, fell onto the power line. Why the tree fell was the subject of analysis in later investigations—an arborist with Cal Fire said the tree was weakened after burning in the 2008 Butte Lightning Complex, while another arborist hired by PG&E noted possible root rot.[29] When the tree fell onto the line, two fuses blew, but one remained active, keeping the power line energized. The tree, in contact with both the line and the ground, created an electrical fault. Electric arcing gradually ignited the receptive fuel bed on the ground over the following hours.[28]

At 1:30 PM, a PG&E troubleman (a lineworker that responds to outages) responded to address the power outage. The roads to access the power lines were in poor condition, and the troubleman was forced to stop at a bridge undergoing repairs. The troubleman left and returned at approximately 4:30, continuing up the road to the power lines and arriving 10 minutes later. Noticing the two blown fuses, the troubleman was in the process of shutting off the third when he smelled smoke—looking down, he observed a fire approximately 600 to 800 square feet in size, burning among pine needles. The troubleman shut off the third fuse, then took a fire extinguisher from his truck and unsuccessfully attempted to put the fire out. He was able to raise his supervisor on the radio, who called 911. In the meantime, the troubleman returned to the fire with another fire extinguisher and a McLeod tool, attempting to dig a firebreak.[28]

Around this time, as the fire became visible from Highway 70 at the bottom of the opposite side of the Feather River Canyon, multiple 911 calls reported the fire. An fire engine strike team leader returning home from the Beckwourth Complex called 911 at roughly 5:12 PM, reporting the well-established fire, about 40 ft. by 40 ft. burning beneath the power lines.[28]

By 5:15 PM, the Oroville emergency command center had dispatched a full wildland response, including 6 fire engines, 2 bulldozers, 2 handcrews, 2 water tenders, 2 airtankers, and a helicopter. The aircraft were overhead by 5:42 PM, reporting that the now-named Dixie Fire was 2 acres with a slow rate of spread, and promptly began to drop water and fire retardant around the fire. By 6:31, aircraft had completed a line of fire retardant around the entire perimeter, and the fire remained 2 acres. The ground-based personnel, however, faced the same access issues that had plagued the PG&E troubleman, including the damaged bridge and nearly impassable dirt roads.[28]

Compounding the struggle to attack the fire aggressively, at 7:49 PM a drone was reported in the vicinity of the fire, and all aircraft were ordered to leave the area. Because it was so late in the evening and regulations do not permit most firefighting aircraft to fly at night, air operations were not able to resume that night. The drone's appearance meant about 45 minutes of flying time was lost, which Butte County District Attorney Mike Ramsey said played a large role in the fire escaping control after dark. The drone's operator was never identified, even after investigation.[28][30]

At this point during the night of July 13, with aircraft no longer able to help, limited ground access, and the fire exposed to up-canyon winds, the Dixie Fire began to grow considerably.

—————————————

PG&E inspectors patrolled the area in November 2020 and January 2021.[31]

Slope of 50 degrees at 2400 feet elevation. Tree Douglas fir 65 feet tall, approx 90 years old, approx 15.8 inches diameter, damaged in 2008 Butte Lightning Complex, fell and contacted conductors at approx. 6:48 AM PDT. Two fuses blew, one remained closed and kept the line energized. "The tree being in contact with energized conductors and the ground created a high impedance fault" Heat and arcing slowly ignited through the tree to the receptive fuel bed, until PG&E troubleman arrived at 4:55 PM. Fire visible from Highway 70 at abt the same time, prompted multiple 911 calls.

1:30 PM troubleman drives up road, stopped at bridge for repairs. Repairs done 3:20 PM ish

4:30 troubleman returns to bridge

4:40 troubleman arrives at fuses

+2 hrs, troubleman arrives at powerlines, pulls 3rd fuse, notices smoke and fire, 600-800 square feet. only in pine needles and attempted to put out himself, using entire fire extinguisher, but fire got into manzanita bush. Returned to truck, supervisor calling on radio. He told supervisor, supervisor told 911. Troubleman returned to fire with other pressurized fire extinguisher and McLeod tool, tried to dig firebreak.https://s1.q4cdn.com/880135780/files/doc_downloads/wildfire_updates/2021/07/1408.pdf

4:45-5 PM PG&E employee overhears troubleman on radio sounding frantic abt fire

5:07 call from PG&E employee at Rock Creek Powerhouse, relaying secondhand info.

5:12 call from engine strike team leader coming home from Beckwourth. Reported well-established 40x40 ft fire burning under powerlines.

5:15 Oroville wildland response, details in report

5:42 PM, aircraft arrive overhead, 2 acres, slow ROS

6:31 holding at 2 acres retardant all around

7:49 drone reported

8:01 air ops halted bc of drone

No lightning for 7 days previously, not a holdover.

Tree that fell had possible rot. Was 70 feet tall, seemed healthy. This ref also can tie into impacts: CPUC and others wanting aggressive line clearance/tree cutting[32] Investigators removed tree parts, equipment, etc. over days after ignition

What did Cal Fire report criticize? Delayed response, no deenergization, in area/time known for bad fires, so close to Camp Fire ignition point.

July[edit]

[EXPAND AND SMOOTH CONSIDERABLY]

Early on, Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E) stated that it believes the fire may have been started by its equipment, sparking the fire near the same network of PG&E power lines where the Camp Fire originated.[33][34] A minor power outage was detected on the morning of July 13.[35] A PG&E maintenance worker, who had been considerably delayed by bridge repairs blocking his route to the remote site, arrived to find a fallen tree on a live power line.[35] It had started a small brush fire. He attempted to extinguish the blaze by himself, without success. Cal Fire sent aircraft to drop water on the fire. Ground crews tried to reach the site, but they were delayed by poor roads.[35] An illegal drone appeared over the fire, endangering and forcing a premature halt to helicopter operations that were intended to extinguish the blaze and which may have "played a major part in the blaze burning out of control after darkness fell."[35]

Over the next few days the fire progressed rapidly northeast along the Feather River canyon, forcing the closure of Highway 70, the Union Pacific Railroad’s Feather River Route, and nearby areas of the Plumas National Forest and Lassen National Forest. By July 19 it had burned 40,500 acres (16,400 ha); over the next two days, the fire more than doubled in size to 85,000 acres (34,000 ha), driven by high winds.[36] As of July 21, the fire was 15 percent contained, with nearly 4,000 firefighters and numerous aircraft assigned to the incident.[37]

By July 23, flames had traveled north almost to Highway 89 and Lake Almanor, after jumping over Butte Valley Reservoir. On the east flank, the fire was advancing toward Bucks Lake and Indian Valley, and on the west, it was burning toward Butte Meadows. It had grown to 167,430 acres (67,760 ha) with 18 percent containment.[38] Governor Gavin Newsom declared a state of emergency for Plumas, Butte, Lassen and Alpine counties due to the Dixie, Fly and Tamarack Fires.[39]

On July 24 the fire expanded rapidly east, burning through Paxton and then Indian Falls, destroying around a dozen structures.[40] Firefighters successfully kept the fire north of Bucks Lake, while flames approached the Indian Valley communities of Crescent Mills, Greenville and Taylorsville on the east. Later that night it merged with the smaller Fly Fire, which had started the previous day north of Quincy and burned over 4,300 acres (1,700 ha).[41] The Dixie Fire grew to 181,289 acres (73,365 ha) with 19 percent containment.[42]

On July 30 the fire was at 240,595 acres (97,365 ha), becoming the 11th largest wildfire in California history, having grown 20,000 acres (8,100 ha) in a single day. However, much of the growth was due to islands of unburned vegetation within the fire perimeter, as well as back burning operations to protect homes in Butte Meadows and Jonesville.[43] Firefighters also contained the eastward spread of the fire with back burning from Mount Hough down to Quincy.[44]

August[edit]

At the start of August, the fire was most active on the north flank, having split into two main branches, with one burning up the western shore of Lake Almanor, and the other burning northeast toward Indian Valley. Fire activity was greatly decreased along the south side from Bucks Lake to Quincy, as well as the west side around Butte Meadows. Beginning on August 3, after several days of calmer weather, a major wind event drove the fire up the west shore of Lake Almanor, threatening Chester and other nearby communities. Firefighting efforts were concentrated on protecting the town, while the fire front continued sweeping north into Lassen County, the Lassen National Forest and the eastern side of Lassen Volcanic National Park.[46]

On the evening of August 4, the northeast flank of the fire jumped containment lines at Indian Valley and burned through the town of Greenville. An estimated 75 percent of structures in Greenville were destroyed, including much of the downtown and numerous nearby homes. The firestorm was compared to "a huge tornado" and took less than half an hour to destroy the town before leaping to the other side of Indian Valley and continuing northeast towards Mountain Meadows Reservoir.[47] The whole Dixie Fire grew to over 320,000 acres (130,000 ha), an increase of 50,000 acres (20,000 ha) in the previous two days, and was 35 percent contained. It became the sixth-largest wildfire in California history, surpassing the North Complex that burned nearby in 2020.[48][49]

On August 5, the fire burned much of Canyondam as it approached the eastern shore of Lake Almanor.[50] By the morning of August 8, the fire had grown to 463,477 acres (187,562 ha), surpassing the 2018 Mendocino Complex Fire to become the second largest fire in the state's history, with containment falling to 21 percent.[51][5] Starting on August 13 increased winds pushed flames primarily to the east. The northern section of the fire expanded around the north side of Lake Almanor, heading east and south and threatening Westwood.[52] The fire's eastern section, having burned past Indian Valley, continued to race east towards Antelope Lake.[citation needed] It became the first fire to ever cross from the west side of the Sierra Nevada to the valley floor on the east side.[13][14]

In the evening of August 16, winds of up to 30 mph (48 kmh) drove embers from the Dixie Fire over the Diamond Mountains and into the Honey Lake Valley. A number of spot fires ignited south of Janesville and crossed Highway 395, destroying several homes.[53] This put areas south of Johnstonville under mandatory evacuation warning, including the town of Janesville. Continued southwest winds threatened to push the fire towards Susanville.[54] In Lassen National Park, the area burned within the park had doubled to 22,000 acres (8,900 ha), and firefighters were building line to protect Manzanita Lake and Old Station areas.[55]

On August 18, the Dixie Fire merged with the Morgan Fire, which had been started by lightning August 12, near the south entrance of Lassen National Park. In addition to burning north into the park, the Morgan Fire had threatened the communities of Mineral and Mill Creek just to the south. The Morgan and Dixie fires were joined by a backfire set in order to reduce fuels adjacent to the two towns.[56] By the end of the day, the Dixie Fire had grown to over 635,000 acres (257,000 ha), an increase of more than 80,000 acres (32,000 ha) since August 15, with containment at 33 percent.[57][58]

By August 22, the Dixie Fire approached Milford but crews were able to protect the structures and containment rose to 37%, the highest since the fire began. Growth of the fire slowed overnight due to increased humidity but overall weather conditions remained challenging.[59]

Associated arson[edit]

In late July and early August of 2021, U.S. Forest Service investigators allegedly foiled an alleged spree of wildland arson by former university professor Gary Stephen Maynard in the vicinity of the Dixie Fire. Investigators ultimately connected Maynard to at least five separate fires, all of which were suppressed at 1 acre or smaller in size, and which did no serious damage. However, the Moon, Ranch, and Conard fires were set behind crews battling the Dixie Fire. Prosecutors seeking to prevent Maynard's release while awaiting trial argued that the fires might have seriously endangered those personnel, leaving them trapped between the Dixie Fire and Maynard's fires, had investigators not already been tracking Maynard and able to detect the fires early on.[60][61]

On July 20, 2021, mountain bikers reported the Cascade Fire on the western slope of Mount Shasta. A responding Forest Service investigator encountered Maynard attempting to free his car from a rut on a dirt road nearby, and took a photo of the car and its tire tracks. The next day, investigators responding to the Everitt Fire in a nearby part of the Shasta-Trinity National Forest noted identical tire tracks. Both fires were determined to have been caused by arson; additionally, burnt newspaper and a match were found where Maynard's car had been stuck. After linking Maynard to the two fires via several other methods, including surveillance footage and his use of an electronic benefit transfer (EBT) card, investigators received a warrant to track Maynard's phone and vehicle. On August 3, 2021, during a stop for a traffic violation in Susanville, a Forest Service agent placed a tracking device on Maynard's car. On August 5, the agents tailing Maynard discovered the roadside Moon Fire, in an area of the Lassen National Forest under an evacuation order for the fast-growing Dixie Fire. Maynard continued to camp in Lassen National Forest despite emergency closure orders, and on August 7 agents discovered the Ranch and Conard fires burning near Maynard's campsite. Tracking data supported his presence at the scenes of ignition.[61]

Maynard was arrested on August 7 by a California Highway Patrol officer, and indicted by a federal grand jury on November 18, 2021. Multiple people who encountered Maynard prior to his arrest and indictment expressed concerns about his mental state. Maynard remains in custody awaiting trial, where if convicted he may face up to 20 years in prison and fines of $250,000 per count of arson.[62][63][64] The arrest of Maynard and of Alexandra Souverneva a month later for starting the destructive Fawn Fire near Redding prompted many to downplay the role of climate change, and spread rumors and conspiracy theories about causes of California wildfires.[65]

---

On August 10, Gary Stephen Maynard, a former University professor, was charged with starting a fire near the perimeter of the Dixie fire. On July 20, 2021, a U.S. Forest Service investigator had encountered him where a small fire had been set and referred to as the Cascade Fire. The investigator photographed Maynard's vehicle.[66] Tire tracks similar to those made by Maynard's vehicle had been found near the 300-acre (almost 1/2 square mile) Bradley Fire on July 11 and the negligible Everitt Fire on July 21 in the Shasta-Trinity National Forest.[66] On August 3, using a traffic stop as a subterfuge to distract Maynard, an investigator placed a magnetic tracking device on the suspect's car while he was in the vicinity of the Moon Fire which had ignited August 5,[67] and the Ranch and Conard fires, which ignited on August 7, in Lassen National Forest.[66] He was also believed to have been in the vicinity of the Sweetbriar Fire, that started on August 6. Deputies from Lassen County took Maynard into custody when he was discovered in an emergency closure area close to the Conard Fire.[66] In 2020, a former colleague of Maynard had alerted San Jose, California police to his alarming mental state.[66] Through obtaining his phone number recorded in that report, investigators traced the locations of his associated cell phone and his use of an Electronic benefit transfer (EBT) card to the vicinities of still more fires.[67] The charging documents indicated that the fires had been set behind first responders who were engaged in fighting blazes, compromising their safety. Thanks to a subpoena, investigators were being alerted by Verizon Wireless of Maynard's location every 15 minutes before his apprehension.[67]

September[edit]

The fire continued burning in the two management zones, the East Zone and West Zone. The eastern zone was mostly Plumas National Forest and the western zone was mostly Lassen Volcanic National Park and Lassen National Forest. The eastern zone extended to the escarpment south of Milford, where firefighters continued efforts to protect the town. By September 6, containment had reached 57%, but extreme fire activity continued and strong winds pushed the fire down off the escarpment to containment lines at the base of the slope.[68][69] By September 10, fire crews were "mopping up" heat near the fire's edge south of Milford. in the West Zone, winds pushed the fire to the northeast, threatening Hat Creek, and Old Station.[70] Old Station was put under evacuation orders on September 8, and by the 10th, the fire had jumped containment lines and crossed Highway 44.[71] Fire crews began using Union Pacific Railroad’s fire train, which can deliver 30,000 gallons of water per load to fill water tenders.[70] On September 9, the weather became more favorable, especially in the West Zone, with calm winds, cooler temperatures down into the 30s overnight, up to a quarter-inch of rain, and rising humidity resulting in minimal fire activity. Favorable conditions were expected to continue throughout the week.[72] As of September 13, the few remaining areas of persistent heat and flames were all within the interior of the burned area,[73] and containment had increased to 86% by September 16.[74] By 18 September, the fire was 88% contained; firefighters reinforced containment lines and monitored/patrolled the fire for hot spots within the fire lines.[75] As of 18 September, fire crews continued to monitor, patrol, and respond to hotspots within the fire. Weather conditions deteriorated leading to potential increase in fire activity due to the increased winds.[75] Rain and work by firefighters on 19 September kept fire activity within the existing perimeter and the increase in reported acreage reflected vegetation burned within that perimeter.[76] On 22 September, containment reached 95% and firefighters successfully contained the last portion of uncontained fire in the Devil's Punchbowl area of the East Zone.[77] On 1 October, Devil's Punchbowl was devoid of heat based on infrared data and InciWeb indicated a 94% overall containment for the Dixie Fire (East and West Zone).[78]

January 2022 - cause determined[edit]

On January 4, 2022, CalFire determined that "the Dixie Fire was caused by a tree contacting electrical distribution lines owned and operated by Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) located west of Cresta Dam." CalFire forwarded the investigative report to the Butte County District Attorney's office, the same federal office that prosecuted PG&E in 2018 following the Camp Fire.[2] PG&E pled guilty to 85 felonies in that case.[79]

Though the 2018 and 2021 fires were both ignited in the Feather River canyon - ignitions were about 5 miles apart[80] - the Camp Fire was caused by a faulty hook on a transmission tower that resulted in a power line touching the ground,[81] while the Dixie Fire was caused by a "healthy green tree" falling and striking distribution lines.[82]

Detailed chronologies and visualizations[edit]

- Anatomy of a wildfire: How the Dixie Fire became the largest blaze of a devastating summer[83]

- See How the Dixie Fire Created Its Own Weather: This year’s largest blaze generated powerful storm clouds. We show you in 3-D.[84]

- Inside the Massive and Costly Fight to Contain the Dixie Fire[85]

Impacts[edit]

A Los Angeles Times column estimated that it might take $1 billion to rebuild the town of Greenville. Meanwhile, only 300 residents plan to return.[86]

On April 11, 2022, PG&E reached a settlement agreement with multiple California county prosecutors. Paid $55 million in exchange for...[87]

https://www.plumasnews.com/da-answers-questions-regarding-pge-settlement-for-dixie-fire/

Casualties and damage[edit]

The Dixie Fire destroyed 1,329 structures,[1] of which at at least 600 were residential. It damaged another 96 structures, and threatened 14,000 more.[88][89] Communities that were largely destroyed by the fire include Greenville, Canyondam, and Indian Falls. In downtown Greenville the fire destroyed multiple historic buildings, many dating back to the 19th-century California Gold Rush. In Lassen National Park, the fire destroyed the Mount Harkness Fire Lookout and possibly other historic facilities within the park.[90] The Tásmam Koyóm valley that was returned to the Maidu as part of the Pacific Gas and Electric Company bankruptcy in 2019 lost a historic stagecoach stop and suffered damages to its cattle-grazing and culturally significant planting areas.[83]

Three firefighters were injured on the Dixie Fire. One fatality was reported: a firefighter died due to COVID-19 illness suspected to have been contracted during suppression efforts.[5][91]

Evacuations[edit]

On July 21, evacuation orders were issued for Butte Meadows in northeast Butte County and the west shore of Lake Almanor in Plumas County, while the east shore of Almanor and the town of Chester were under an evacuation warning.[93][94] By July 24 evacuation orders were extended to Greenville, Crescent Mills, Taylorsville, and other communities along the Feather River canyons east and west of the fire, as well as Bucks Lake, Meadow Valley and parts of Quincy.[95] As of July 25, about 7,400 people in Plumas County and 100 people in Butte County had been evacuated.[41]

On August 3, Chester, Lake Almanor Peninsula and Hamilton Branch were evacuated as the fire advanced north toward Lassen National Park, bringing the total number of people evacuated to 26,500.[96] On August 4 evacuation orders were issued in southwest Lassen County, particularly the areas south of Highway 44 and Mountain Meadows Reservoir, and evacuation warnings for Westwood and Pine Town.[97]

A list of previous evacuation orders is available from Cal Fire.

Closures[edit]

On July 24, Lassen National Park was closed to backcountry camping, and the Warner Valley and Juniper Lake areas were closed to all visitors.[98] On August 5, the entire park was closed to visitors as the Dixie Fire burned into the eastern side of the park.[47]

As of August 2, State Routes 32, 89, 147, 36, and 70 were closed to through traffic in the area of the Dixie Fire.[99]

Air pollution[edit]

Smoke from the Dixie Fire caused unhealthy air quality throughout the Western United States.[15] On August 6 in Salt Lake City the small airborne particulates (PM2.5) level spiked to more than 3 times the federal standard, and caused the area to temporarily have the worst air quality in the world.[16][17] The particulates causing the poor air quality in Utah came from the Dixie and other fires. In early August, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment reported unhealthy air pollution levels in much of the state.[18]

While not attributed specifically to the Dixie Fire, air quality in New York City was poorer than usual during the summer of 2021 due to wildfires in the western U.S.[100][101]

Costs[edit]

The Dixie Fire resulted in the most expensive wildfire suppression effort in United States history, in part due to a reliance on contracted and higher-paid local and private firefighters. The final cost of containing the Dixie Fire came to $637.4 million, split between multiple agencies such as CAL FIRE and the U.S. Forest Service.[102][19]

Progression and containment status[edit]

| Date | Area burned acres (km2) |

Containment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jul 14 | 2,200 (9)[103] | 0%

| ||

| Jul 16 | 8,754 (35)[104] | 0%

| ||

| Jul 17 | 9,847 (40)[105] | 9%

| ||

| Jul 18 | 15,074 (61)[106] | 15%

| ||

| Jul 19 | 30,074 (122)[107] | 15%

| ||

| Jul 20 | 59,984 (243)[108] | 15%

| ||

| Jul 21 | 85,479 (346)[109] | 15%

| ||

| Jul 22 | 103,910 (421)[110] | 17%

| ||

| Jul 23 | 167,430 (678)[38] | 18%

| ||

| Jul 24 | 181,289 (734)[111] | 19%

| ||

| Jul 25 | 190,625 (771)[112] | 21%

| ||

| Jul 26 | 197,487 (799)[113] | 22%

| ||

| Jul 27 | 212,799 (861)[114] | 23%

| ||

| Jul 28 | 217,581 (881)[115] | 23%

| ||

| Jul 29 | 221,504 (896)[116] | 23%

| ||

| Jul 30 | 240,595 (974)[117] | 24%

| ||

| Jul 31 | 244,388 (989)[118] | 30%

| ||

| Aug 1 | 248,570 (1,006)[119] | 33%

| ||

| Aug 2 | 249,635 (1,010)[120] | 35%

| ||

| Aug 3 | 253,052 (1,024)[121] | 35%

| ||

| Aug 4 | 274,139 (1,109)[122] | 35%

| ||

| Aug 5 | 322,502 (1,305)[123] | 35%

| ||

| Aug 6 | 432,813 (1,752)[124] | 35%

| ||

| Aug 7 | 446,723 (1,808)[125] | 21%

| ||

| Aug 8 | 463,477 (1,876)[126] | 21%

| ||

| Aug 9 | 489,287 (1,980)[127] | 21%

| ||

| Aug 10 | 487,764 (1,974)[128] | 25%

| ||

| Aug 11 | 505,413 (2,045)[129] | 30%

| ||

| Aug 12 | 515,756 (2,087)[130] | 31%

| ||

| Aug 13 | 517,945 (2,096)[131] | 31%

| ||

| Aug 14 | 540,581 (2,188)[132] | 31%

| ||

| Aug 15 | 554,816 (2,245)[57] | 31%

| ||

| Aug 16 | 569,707 (2,306)[133] | 31%

| ||

| Aug 17 | 604,511 (2,446)[134] | 31%

| ||

| Aug 18 | 635,728 (2,573)[58] | 33%

| ||

| Aug 19 | 678,369 (2,745)[135] | 35%

| ||

| Aug 20 | 700,630 (2,835)[136] | 35%

| ||

| Aug 21 | 714,219 (2,890)[137] | 36%

| ||

| Aug 22 | 721,298 (2,919)[59] | 37%

| ||

| Aug 23 | 725,821 (2,937)[138] | 40%

| ||

| Aug 24 | 731,310 (2,960)[139] | 41%

| ||

| Aug 25 | 735,064 (2,975)[140] | 45%

| ||

| Aug 26 | 747,091 (3,023)[141] | 45%

| ||

| Aug 27 | 750,672 (3,038)[142] | 48%

| ||

| Aug 28 | 756,768 (3,063)[143] | 48%

| ||

| Aug 30 | 771,183 (3,121)[144] | 48%

| ||

| Aug 31 | 807,396 (3,267)[145] | 48%

| ||

| Sep 1 | 844,081 (3,416)[146] | 52%

| ||

| Sep 2 | 859,457 (3,478)[147] | 55%

| ||

| Sep 3 | 868,781 (3,516)[148] | 55%

| ||

| Sep 4 | 885,954 (3,585)[149] | 55%

| ||

| Sep 5 | 893,852 (3,617)[150] | 56%

| ||

| Sep 6 | 910,495 (3,685)[68] | 57%

| ||

| Sep 7 | 917,579 (3,713)[151] | 59%

| ||

| Sep 8 | 922,192 (3,732)[152] | 59%

| ||

| Sep 9 | 927,320 (3,753)[153] | 59%

| ||

| Sep 10 | 950,591 (3,847)[70] | 59%

| ||

| Sep 11 | 959,253 (3,882)[154] | 62%

| ||

| Sep 12 | 960,213 (3,886)[72] | 65%

| ||

| Sep 13 | 960,335 (3,886)[73] | 75%

| ||

| Sep 14 | 960,470 (3,887)[155] | 75%

| ||

| Sep 15 | 960,470 (3,887)[156] | 75%

| ||

| Sep 16 | 960,470 (3,887)[74] | 86%

| ||

| Sep 17 | 960,581 (3,887)[157] | 86%

| ||

| Sep 18 | 960,641 (3,888)[75] | 88%

| ||

| Sep 19 | 963,301 (3,898)[76] | 88%

| ||

| Sep 20 | 963,195 (3,898)[158] | 90%

| ||

| Sep 21 | 963,276 (3,898)[159] | 90%

| ||

| Sep 22 | 963,276 (3,898)[77] | 95%

| ||

| Sep 26 | 963,276 (3,898)[160] | 94%

| ||

| Sep 27 | 963,276 (3,898)[161] | 94%

| ||

| Sep 28 | 963,309 (3,898)[162] | 94%

| ||

| Sep 29 | 963,309 (3,898)[163] | 94%

| ||

| Sep 30 | 963,309 (3,898)[164] | 94%

| ||

| Oct 01 | 963,309 (3,898)[165] | 94%

| ||

| Oct 02 | 963,309 (3,898)[166] | 94%

| ||

| Oct 17 | 963,309 (3,898)[167] | 94%

| ||

| Oct 18 | 963,309 (3,898)[168] | 94%

| ||

| Oct 19 | 963,309 (3,898)[169] | 95%

| ||

| Oct 20 | 963,309 (3,898)[170] | 95%

| ||

| Oct 21 | 963,309 (3,898)[171] | 97%

| ||

| Oct 22 | 963,309 (3,898)[172] | 97%

| ||

| Oct 23 | 963,309 (3,898)[173] | 97%

| ||

| Oct 24 | 963,309 (3,898)[174] | 97%

| ||

| Oct 25 | 963,309 (3,898)[7] | 100%

|

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Dixie Fire (CA) Information". CAL FIRE. September 21, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2021.

- ^ a b c "CAL FIRE Investigators Determine Cause of the Dixie Fire" (PDF) (Press release). Butte County: California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. 4 January 2022. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- ^ Kasler, Dale (3 November 2021). "PG&E says Dixie Fire will cost $1.15 billion – and is being probed by federal officials". The Sacramento Bee. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- ^ Ramsey, Michael L. (5 January 2022). "Investigation into Dixie Fire Continues" (PDF) (Press release). Butte County District Attorney. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Top 20 Largest California Wildfires" (PDF). California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. September 20, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2021.

- ^ Cowan, Jill; Stevens, Matt (2021-08-06). "How do wildfires get their names?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-03-17.

- ^ a b "Dixie Fire Update, Monday, October 25, 2021" (PDF). October 25, 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-10-26.

- ^ Colby Bermel (August 6, 2021). "Dixie Fire becomes largest single wildfire in California history". Politico. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ "Aircraft help fight California wildfire as smoke clears", Associated Press, August 9, 2021.

- ^ "California's Dixie Fire demolishes two mountain communities". CBS News. August 6, 2021. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire: California's largest fire burns over 220,000 acres". KCRA. July 30, 2021. Archived from the original on July 30, 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ^ Amy Graff (July 23, 2021). "Dixie Fire grows to largest California wildfire so far in 2021". SFGate.

- ^ a b Paulina Firozi; Marisa Iati (August 18, 2021). "Caldor Fire explodes, leveling parts of a California town and forcing thousands to evacuate". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ a b Scott Reinhard; Jugal K. Patel (September 6, 2021). "Caldor Fire's March to the Edge of South Lake Tahoe". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 6, 2021.

- ^ a b Bacon, John (August 8, 2021). "Dixie Fire, largest single blaze in California history, threatens thousands of homes; state's fire season could surpass 2020 mark". USA Today. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ^ a b Maffly, Brian (August 7, 2021). "Air quality remains poor as West Coast smoke continues to linger over much of Utah". The Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ^ a b Peery, Lexi (August 6, 2021). "Utah Had The Worst Air In The World Today — Here's What You Need To Know To Be Safe". KUER-FM. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ^ a b "Wildfire Smoke Continues to Flow Into Colorado, Utah". U.S. News & World Report. August 8, 2021. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ^ a b Alexander, Kurtis (2022-03-18). "Last year's fire season in California set record for cost, Dixie Fire most expensive in U.S. history". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2022-03-20.

- ^ Smith, Hayley (2021-09-09). "California records its hottest summer ever as climate change roils cities". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2022-09-28.

- ^ a b Fountain, Henry (2021-05-19). "Severe Drought, Worsened by Climate Change, Ravages the American West". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-09-28.

- ^ Williams, A. Park; Cook, Benjamin I.; Smerdon, Jason E. (2022-02-14). "Rapid intensification of the emerging southwestern North American megadrought in 2020–2021". Nature Climate Change. 12 (3): 232–234. doi:10.1038/s41558-022-01290-z. ISSN 1758-6798.

- ^ Smith, Hayley; Seidman, Lila (2021-09-09). "After a disastrous summer of fire, California braces for a potentially worse fall". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2022-09-28.

- ^ Johnson, Julie (2021-08-29). "The fires are different this year — bigger and faster. What's fueling the change?". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 2022-04-13. Retrieved 2022-09-28.

- ^ Gabbert, Bill (2021-08-06). "Most of the vegetation in the Dixie Fire has not burned in more than 40 years". Wildfire Today. Retrieved 2022-09-28.

- ^ Benda, David; Chapman, Mike (2021-08-12). "Dry, hot, windy: Explosive wildfires in Northern California could burn until winter". USA Today. Retrieved 2022-09-28.

- ^ "Bark beetles, tree chemistry, and wildfires". U.S. Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station. Retrieved 2022-09-28.

- ^ a b c d e f "PG&E Responds to CAL FIRE's Report on 2021 Dixie Fire in Butte, Lassen, Plumas, Shasta, and Tehama Counties & CAL FIRE Investigation Report: DIXIE" (PDF). PG&E Corporation. 2022-06-09. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-09-27. Retrieved 2022-09-27.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 2022-09-28 suggested (help) - ^ Van Derbeken, Jaxon (2021-09-07). "Massive Dixie Fire in Northern California Tied to Rotted Tree". NBC Bay Area. Retrieved 2022-09-27.

- ^ Brekke, Dan (2021-07-22). "Why It Took PG&E 9.5 Hours to Get to the Scene Where Dixie Fire Started". KQED. Retrieved 2022-09-27.

- ^ "Cal Fire Dixie Fire report" (PDF). Archived from the original on 2022.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|archive-date=(help) - ^ Derbeken • •, Jaxon Van. "Massive Dixie Fire in Northern California Tied to Rotted Tree". NBC Bay Area. Retrieved 2022-09-27.

- ^ Allen, Meredith (July 18, 2021). "Electric Safety Incident Reported- PG&E Incident No: 210718-14913" (PDF). California Public Utilities Commission. Retrieved September 10, 2021.

- ^ Rittiman, Brandon (July 19, 2021). "Prosecutors investigate PG&E as company admits it may have sparked the Dixie Fire". ABC 10 News. Associated Press. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Brecke, Dan (July 22, 2021). "Why It Took PG&E 9.5 Hours to Get to the Scene Where Dixie Fire Started". KQED. Retrieved August 14, 2021.

- ^ Amy Graff (July 21, 2021). "California's Dixie Fire in the Feather River Canyon explodes to 85,479 acres". SFGate.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Daily Update for July 21". InciWeb. July 21, 2021. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ a b "Dixie Fire Update for July 23" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ Hernández, Lauren; Rashad, Omar Shaikh (July 24, 2021). "Newsom declares state of emergency as Dixie Fire explodes to 167,000 acres". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ "California's largest fire torches homes as blazes lash West". AP NEWS. July 25, 2021.

- ^ a b SFGATE, Amy Graff (July 25, 2021). "'Devastating': California's largest fire devours multiple homes". SFGATE.

- ^ Gardner, Ashley (July 24, 2021). "More than 10,000 structures threatened as Dixie Fire grows to more than 180,000 acres". KRCR.

- ^ SFGATE, Amy Graff; SFGATE, Michelle Robertson (July 30, 2021). "More evacuation orders due to still-growing Dixie Fire". SFGATE.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update 7/31 7 a.m. - InciWeb the Incident Information System". inciweb.nwcg.gov. July 31, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- ^ "California's Dixie Fire Keeps on Growing". NASA Earth Observatory. August 7, 2021. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ^ Christal Hayes; David Benda; Jessica Skropanic; Damon Arthur; Terell Wilkins (August 5, 2021). "'Catastrophically destroyed': Dixie Fire wipes out California gold rush town of Greenville". USA Today. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- ^ a b Ryan Sabalow; Amelia Davidson; Dale Kasler (August 8, 2021). "'The town is completely gone.' Dixie Fire devastates California Gold Rush town of Greenville". The Sacramento Bee. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "'We lost Greenville': Dixie Fire destroys much of California Gold Rush town". KTLA. AP. August 5, 2021. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire (CA)". InciWeb. National Wildfire Coordinating Group. August 5, 2021. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update: Buildings Burn In Canyondam; Fire Advance Forces Lassen Park Closure; 4 Missing In Plumas County". sanfrancisco.cbslocal.com. August 6, 2021.

- ^ "Update: Dixie Fire Tops 432,000 Acres; Largest Current Wildfire In U.S.; 4 Missing In Plumas County". August 6, 2021.

- ^ Ashley Gardner (August 13, 2021). "People in Westwood urged to 'leave immediately' due to Dixie Fire". krcrtv.com. Archived from the original on August 17, 2021.

- ^ Damon Arthur; David Benda; Terell Wilkins; Michele Chandler (August 17, 2021). "Dixie Fire: More than 626,000 acres burned, evacuations ordered for Janesville, Milford". Redding Record Searchlight. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "'Next 24 hours critical', as crews battle largest wildfire in US". aljazeera.com. August 17, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ David Benda (August 17, 2021). "As Dixie Fire size doubles inside Lassen park, crews fight to keep flames from Manzanita Lake, Old Station". Redding Record Searchlight. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Ashley Harrell (August 18, 2021). "More than a third of Lassen Volcanic National Park has been torched". SFGate. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ a b "Dixie Fire Update for August 15". National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ a b "Dixie Fire Update for August 18" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ a b "Dixie Fire Update for August 22" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ Gabbert, Bill (2021-08-11). "Former university professor charged with arson near the Dixie Fire". Wildfire Today. Retrieved 2022-09-29.

- ^ a b "United States of America v. Gary Stephen Maynard - Criminal Complaint" (PDF). United States District Court for the Eastern District of California. 2021-08-08. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-08-06. Retrieved 2022-09-29.

- ^ Hauser, Christine (2021-11-19). "Former Professor Is Indicted in 'Arson Spree' in California". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-09-29.

- ^ Rice, Andrew (2022-07-20). "How Professor Maynard Burned Down: The criminologist on trial for serial arson". Intelligencer. New York Magazine. Retrieved 2022-09-29.

- ^ "Professor-Arsonist Indicted for Setting Fires Behind Firefighters Fighting Dixie Fire". United States Department of Justice. 2021-11-18. Retrieved 2022-09-29.

- ^ Anguiano, Dani (2022-10-12). "Why is arson falsely blamed for the US west's wildfire emergency? 'It provides a villain'". The Guardian. Retrieved 2022-09-29.

- ^ a b c d e Jason Green (August 10, 2021). "Ex-Santa Clara University professor charged with setting blaze near Dixie fire". Mercury News. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ a b c Bill Chappell (August 11, 2021). "A Former College Professor Accused Of Serial Arson Is Denied Bail In California". Wisconsin Public Radio. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ a b "Dixie Fire Update for September 6, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 6, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire map (public)" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 6, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Dixie Fire Update for September 10, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 10, 2021.

- ^ Carroll, Mason (2021-09-09). "Dixie Fire jumps Highway 44 and reaches outside of Old Station". KRCR. Retrieved 2021-09-12.

- ^ a b "Dixie Fire Update for September 12, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 12, 2021.

- ^ a b "Dixie Fire Update for September 13, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 13, 2021.

- ^ a b "Dixie Fire Update for September 16, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Dixie Fire Update for September 18, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 18, 2021.

- ^ a b "Dixie Fire Update for September 19, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- ^ a b "Dixie Fire Update for September 22, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire East Zone Update Update for October 1, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ Romo, Vanessa (16 June 2020). "PG&E Pleads Guilty on 2018 California Camp Fire: 'Our Equipment Started That Fire'". NPR.

- ^ "PG&E Power Line May Have Sparked Dixie Fire, Near Where Its Equipment Started State's Deadliest Blaze".

- ^ "Long-Term Wear Found on PG&E Line That Sparked Camp Fire".

- ^ https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/21011766/071821.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ a b Iati, Marisa; Moriarty, Dylan. "Anatomy of a wildfire: How the Dixie Fire became the largest blaze of a devastating summer". Washington Post. Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- ^ Popovich, Nadja; Pisner, Noah; Bartzokas, Nicholas; Grothjan, Evan; Mangosing, Daniel; Patanjali, Karthik; Reinhard, Scott (2021-10-19). "See How the Dixie Fire Created Its Own Weather". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- ^ McDonald, Brent; Burrous, Sashwa; Weingart, Eden; Felling, Meg (2021-10-11). "Inside the Massive and Costly Fight Against the Dixie Fire". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- ^ Smith, Erika D.; Chabria, Anita (2022-09-27). "Column: California spends billions rebuilding burned towns. The case for calling it quits". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2022-09-27.

- ^ Penn, Ivan (2022-04-11). "PG&E agrees to pay $55 million in penalties and costs over two wildfires". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-09-27.

- ^ "Map: Homes and other buildings destroyed by Dixie Fire". Mercury News. August 12, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2021.

- ^ Olafimihan Oshin (August 8, 2021). "Dixie fire grows into California's second-largest in history". The Hill.

- ^ Chapman, Mike. "Dixie Fire destroys historic fire lookout in Lassen Volcanic National Park; more facilities at risk". Redding Record Searchlight.

- ^ "Firefighter assigned to Dixie Fire dies from unrelated illness". mynews4.com. The Associated Press. September 5, 2021. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- ^ Rick Silva (July 24, 2021). "8:20 a.m. UPDATE: Dixie Fire now 181,289; 10 structures confirmed destroyed". Enterprise-Record.

- ^ Omar Shaikh Rashad and Nora Mishanec (July 21, 2021). "California wildfires: Dixie Fire destroys eight structures, threatens Native American archaeological sites". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ "Dixie Fire: More evacuations issued for Northern California wildfire". KCRA Sacramento. July 21, 2021.

- ^ "Thunder threat and dry conditions head in fight against Dixie Fire | Evacuations, maps, updates". abc10.com. 24 July 2021.

- ^ Caballero, Daisy (August 4, 2021). "Chester and Lake Almanor evacuees leave home as Dixie Fire approaches their communities". KRCR-TV. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ Robinson, Adam (August 4, 2021). "Lassen County Sheriff issues new evacuations due to increased activity of the Dixie Fire". KRCR.

- ^ Gardner, Ashley (July 24, 2021). "Lassen National Park announces closures due to Dixie Fire". KRCR-TV. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ "Caltrans announces latest road closures due to the Dixie Fire". Plumas News. August 2, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- ^ Silverman, Hollie; Guy, Michael; Sutton, Joe (21 July 2021). "Western wildfire smoke is contributing to New York City's worst air quality in 15 years". CNN. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- ^ Albeck-Ripka, Livia; Fuller, Thomas; Healy, Jack (9 August 2021). "The Ashes of the Dixie Fire Cast a Pall 1,000 Miles From Its Flames". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ McDonald, Brent; Burrous, Sashwa; Weingart, Eden; Felling, Meg (2021-10-11). "Inside the Massive and Costly Fight Against the Dixie Fire". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-10-13.

- ^ Paul Kitagaki Jr. (July 15, 2021). "Paradise residents concerned as Dixie Fire erupts near site of 2018 Camp Fire". ktla.com. The Sacramento Bee, via Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 9, 2021. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ Bill Gabbert (July 16, 2021). "Dixie Fire very active Friday near Tobin, California". wildfiretoday.com.

- ^ "July 17: Dixie Fire now 9,847 acres; 9 percent contained UPDATED". Plumas News. July 17, 2021. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ "July 18 a.m. update on the Dixie Fire – 15 percent contained". Plumas News. July 18, 2021. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ "July 19: Dixie Fire grows overnight to 30,074 acres". Plumas News. July 19, 2021. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ Anisca Miles (July 20, 2021). "Dixie Fire burns nearly 60,000 acres, remains 15% contained". fox40.com. Associated Press. Archived from the original on July 20, 2021. Retrieved September 18, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for July 21" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for July 22" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for July 24" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for July 25" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for July 26" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for July 27" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for July 28" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for July 29". National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for July 30" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for July 31" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 1" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 2" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 3" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 4" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 5" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 6" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 7" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 8" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 9" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 10" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 11" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 12" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 13". National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 14, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 14". National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 14, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 16" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 17" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 19" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 20" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 21" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 23" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 24" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 25" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 26" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 27, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 28, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 28, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 30, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 30, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for August 31, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for September 1, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for September 2, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for September 3, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for September 4, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 6, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for September 5, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 6, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for September 7, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for September 8, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for September 9, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 9, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for September 11, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 11, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for September 14, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for September 15, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 16, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for September 17, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for September 20, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 21, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for September 21, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for September 26, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire Update for September 27, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire West Zone Update Update for September 28, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire West Zone Update Update for September 29, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire West Zone Update Update for September 30, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire West Zone Update Update for October 01, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire West Zone Update Update for October 2, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved October 2, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire West Zone Update Update for October 17, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire West Zone Update Update for October 18, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire West Zone Update Update for October 19, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire West Zone Update Update for October 20, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire West Zone Update Update for October 21, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire West Zone Update Update for October 22, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire West Zone Update Update for October 23, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ "Dixie Fire West Zone Update Update for October 24, 2021" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Retrieved October 24, 2021.