User:ThunderhillMc/Déjà vu

| This is the sandbox page where you will draft your initial Wikipedia contribution.

If you're starting a new article, you can develop it here until it's ready to go live. If you're working on improvements to an existing article, copy only one section at a time of the article to this sandbox to work on, and be sure to use an edit summary linking to the article you copied from. Do not copy over the entire article. You can find additional instructions here. Remember to save your work regularly using the "Publish page" button. (It just means 'save'; it will still be in the sandbox.) You can add bold formatting to your additions to differentiate them from existing content. |

What is Déjà Vu?[edit]

Déjà Vu is a term used when one experiences a sensation of remembrance about a certain scenario. This phenomena has been reported to cause confusion among those affected because many recall they have experienced a similar event before, even when they know they haven't. Although it is difficult to pinpoint the direct cause of déjà vu due to its spontaneous nature, many scientist believe it is related with the memory function of the brain, and the consciousness of the individual in that moment. The feeling of déjà vu is not uncommon and is typically fleeting. It can be fascinating, but there are usually no major health risks linked with it. The following sections will highlight the history, along some of the reasoning as to why people experience déjà vu in their lifetime.

History[edit]

The term "Déjà Vu" is a derived from the French word for "already seen". Déjà vu occurs when someone has already experienced a situation before, and their body experiences familiarity and confusion. This term was first used by Émile Boirac in the year 1876. Boirac was a French philosopher who wrote a book that included the sensation of déjà vu in his writings, titled "The Psychology of the Future" (LiveScience, Ede). Déjà vu has been presented as a reminisce of memories, "These experiments have led scientists to suspect that déjà vu is a memory phenomenon. We encounter a situation that is similar to an actual memory but we can’t fully recall that memory". This evidence, found by Émile Boirac, helps the public understand what déjà vu can entail on the average brain. It was also stated, ". . . Our brain recognizes the similarities between our current experience and one in the past . . . left with a feeling of familiarity that we can’t quite place" (Scientific American, Stierwalt). Throughout history, there have been many theories on what causes déjà vu. This phenomenon has displayed its difficultly to be tested due to its random occurrence in people.

Memory-Based Explanation[edit]

Implicit memory[edit]

Research has associated déjà vu experiences with good memory functions,[1] particularly long-term implicit memory. Recognition memory enables people to realize the event or activity that they are experiencing has happened before. When people experience déjà vu, they may have their recognition memory triggered by certain situations which they have never encountered.[2] Déjà vu can also be related to the frontal lobes of the brain, relying on the processing of information. When seizures occur in this region, they are considered temporal lobe seizures. Those that experience temporal lobe seizures experience feelings related to anxiety, fear, joy, or déjà vu.[3]

The similarity between a déjà-vu-eliciting stimulus and an existing, or non-existing but different, memory trace may lead to the sensation that an event or experience currently being experienced has already been experienced in the past.[4][5]Thus, encountering something that evokes the implicit associations of an experience or sensation that cannot be remembered may lead to déjà vu. In an effort to reproduce the sensation experimentally, Banister and Zangwill (1941)[6][7] used hypnosis to give participants posthypnotic amnesia for material they had already seen. When this was later re-encountered, the restricted activation caused thereafter by the posthypnotic amnesia resulted in three of the 10 participants reporting what the authors termed "paramnesias".

Two approaches are used by researchers to study feelings of previous experience, with the process of recollection and familiarity. Recollection-based recognition refers to an ostensible realization that the current situation has occurred before. Familiarity-based recognition refers to the feeling of familiarity with the current situation without being able to identify any specific memory or previous event that could be associated with the sensation.[8]

In 2010, O'Connor, Moulin, and Conway developed another laboratory analog of déjà vu based on two contrast groups of carefully selected participants, a group under posthypnotic amnesia condition (PHA) and a group under posthypnotic familiarity condition (PHF). The idea of PHA group was based on the work done by Banister and Zangwill (1941), and the PHF group was built on the research results of O'Connor, Moulin, and Conway (2007).[9] They applied the same puzzle game for both groups, "Railroad Rush Hour", a game in which one aims to slide a red car through the exit by rearranging and shifting other blocking trucks and cars on the road. After completing the puzzle, each participant in the PHA group received a posthypnotic amnesia suggestion to forget the game in the hypnosis. Then, each participant in the PHF group was not given the puzzle but received a posthypnotic familiarity suggestion that they would feel familiar with this game during the hypnosis. After the hypnosis, all participants were asked to play the puzzle (the second time for PHA group) and reported the feelings of playing.

In the PHA condition, the subject was considered to have passed the suggestion if the subject claimed not to have remembered finishing the puzzle game while under hypnosis. In the PHF condition, if participants reported that the puzzle game felt familiar, researchers scored the participant as passing the suggestion. It turned out that, both in the PHA and PHF conditions, five participants passed the suggestion and one did not, which is 83.33% of the total sample.[10] More participants in PHF group felt a strong sense of familiarity, for instance, comments like "I think I have done this several years ago." Furthermore, more participants in PHF group experienced a strong déjà vu, for example, "I think I have done the exact puzzle before." Three out of six participants in the PHA group felt a sense of déjà vu, and none of them experienced a strong sense of it. Some participants in PHA group related the familiarity when completing the puzzle with an exact event that happened before, which is more likely to be a phenomenon of source amnesia. Other participants started to realize that they may have completed the puzzle game during hypnosis, which is more akin to the phenomenon of breaching. In contrast, participants in the PHF group reported that they felt confused about the strong familiarity of this puzzle, with the feeling of playing it just sliding across their minds. Overall, the experiences of participants in the PHF group is more likely to be the déjà vu in life, while the experiences of participants in the PHA group is unlikely to be real déjà vu.

A 2012 study in the journal Consciousness and Cognition, that used virtual reality technology to study reported déjà vu experiences, supported this idea. This virtual reality investigation suggested that similarity between a new scene's spatial layout and the layout of a previously experienced scene in memory (but which fails to be recalled) may contribute to the déjà vu experience.[11] When the previously experienced scene fails to come to mind in response to viewing the new scene, that previously experienced scene in memory can still exert an effect—that effect may be a feeling of familiarity with the new scene that is subjectively experienced as a feeling that an event or experience currently being experienced has already been experienced in the past, or of having been there before despite knowing otherwise.

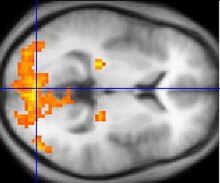

In 2018 a study examined volunteer's brains under experimentally induced déjà vu through the use of fMRI brain scans. The induced "deja vu" state was created by getting them to look at a series of logically related and unrelated words. The researchers would then ask the participants how many words starting with a specific letter they saw. With related words such as "door, shutter, screen, breeze", the participants would be asked if they saw any words that started with "W" (ie. Window, a term that was not presented to the participants). If they did note that they thought they saw a word that wasn't presented to them, then déjà vu was induced. The researchers would then examine the volunteer's brains at the moment of induced déjà vu. From these scans, they noticed that there was visible activity in regions of the brain associated with mnemonic conflict. This finding suggests that more research regarding memory conflict may be important in better understanding déjà vu.[12]

References[edit]

Ede, R. (2023, May 31). What is the science behind déjà vu? livescience.com. https://www.livescience.com/health/psychology/what-is-the-science-behind-deja-vu

Stierwalt, E. E. S. (2020, March 23). Can science explain deja vu? Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/can-science-explain-deja-vu/

- ^ Adachi, N.; Adachi, T.; Kimura, M.; Akanuma, N.; Takekawa, Y.; Kato, M. (2003). "Demographic and psychological features of déjà vu experiences in a nonclinical Japanese population". Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 191 (4): 242–247. doi:10.1097/01.nmd.0000061149.26296.dc. PMID 12695735. S2CID 23249270.

- ^ Cleary, Anne M. (2008-10-01). "Recognition Memory, Familiarity, and Déjà vu Experiences". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 17 (5): 353–357. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00605.x. ISSN 0963-7214. S2CID 55691148.

- ^ "Psychomotor Seizures (Temporal-lobe Seizures)", Encyclopedia of Neuroscience, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 3338–3338, retrieved 2023-10-24

- ^ Brown, Alan S. (2004). The Déjà Vu Experience. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-84169-075-9.

- ^ Cleary AM (2008). "Recognition memory, familiarity and déjà vu experiences". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 17 (5): 353–357. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00605.x. S2CID 55691148.

- ^ Banister H, Zangwill, O (1941). "Experimentally induced olfactory paramnesia". British Journal of Psychology. 32 (2): 155–175. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1941.tb01018.x.

- ^ Banister H, Zangwill, O (1941). "Experimentally induced visual paramnesias". British Journal of Psychology. 32: 30–51. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1941.tb01008.x.

- ^ Cleary, Anne M. (2008). "Recognition Memory, Familiarity, and Déjà vu Experiences". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 17 (5): 353–357. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00605.x. ISSN 0963-7214. S2CID 55691148.

- ^ O'Connor, Akira R.; Moulin, Chris J. A. (2013). "Déjà vu experiences in healthy subjects are unrelated to laboratory tests of recollection and familiarity for word stimuli". Frontiers in Psychology. 4: 881. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00881. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 3842028. PMID 24409159.

- ^ O'Connor, Akira R.; Barnier, Amanda J.; Cox, Rochelle E. (2008-09-02). "Déjà Vu in the Laboratory: A Behavioral and Experiential Comparison of Posthypnotic Amnesia and Posthypnotic Familiarity". International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 56 (4): 425–450. doi:10.1080/00207140802255450. hdl:10023/1647. ISSN 0020-7144. PMID 18726806. S2CID 1177171.

- ^ Cleary; Brown, AS; Sawyer, BD; Nomi, JS; Ajoku, AC; Ryals, AJ; et al. (2012). "Familiarity from the configuration of objects in 3-dimensional space and its relation to déjà vu: A virtual reality investigation". Consciousness and Cognition. 21 (2): 969–975. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2011.12.010. PMID 22322010. S2CID 206954894.

- ^ Urquhart, Josephine A.; Sivakumaran, Magali H.; Macfarlane, Jennifer A.; O’Connor, Akira R. (2021-08-09). "fMRI evidence supporting the role of memory conflict in the déjà vu experience". Memory. 29 (7): 921–932. doi:10.1080/09658211.2018.1524496. ISSN 0965-8211.