User:Tim1965/Sandbox5

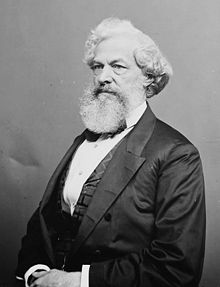

Montgomery Cunningham Meigs | |

|---|---|

Montgomery C. Meigs | |

| Born | May 3, 1816 Augusta, Georgia |

| Died | January 2, 1892 (aged 75) Washington, D.C. |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | United States of America Union |

| Service/ | United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1836 - 1882 |

| Rank | Brigadier General, Brevet Major General |

| Commands held | Quartermaster General |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

| Other work | Smithsonian Institution regent National Academy of Sciences, member |

Montgomery Cunningham Meigs (/ˈmɛɡz/; May 3, 1816 – January 2, 1892) was a career United States Army officer, civil engineer, and construction engineer. He co-designed and oversaw the construction of the Washington Aqueduct (which brought large amounts of fresh water to Washington, D.C., for the first time), the extension of the United States Capitol, and the construction of the United States Capitol dome. During the American Civil War, he was Quartermaster General of the United States Army and one of Abraham Lincoln's most trusted military advisors. He founded Arlington National Cemetery on the grounds of the estate of his former close friend Robert E. Lee, and was superintendent of the cemetery from its creation in 1864 until 1882. He also designed and oversaw construction of the Pension Building.

Early life[edit]

Meigs was born in Augusta, Georgia, in May 1816. He was the son of Dr. Charles Delucena Meigs and Mary Montgomery Meigs.[1] His father was a nationally known obstetrician and professor of obstetrics at Jefferson Medical College[2][3] His grandfather, Josiah Meigs, graduated from Yale University (where he was a classmate of future dictionary creator Noah Webster and American Revolutionary War general and politician Oliver Wolcott), and later was president of the University of Georgia.[3] Montgomery Meig's mother, Mary, was the granddaughter of a Scottish family from Brigend (with somewhat distant claims to a baronetcy) which emigrated to America in 1701.[4]

Meig's father apprenticed as a physician in Philadelphia until 1812, at which time he moved to Athens, Georgia. He enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania in 1815, the same year he began to practice medicine in Georgia. Charles Meigs received his M.D. from the University of Pennsylvania in 1817, and that summer he moved his family—which now included one-year-old Montgomery—to Philadelphia and established a practice there.[5] The move was prompted by Mary Meigs, who was deeply upset by slavery and found she could not live among slave-owners.[6] The Meigs family was wealthy and well-connected, and Charles Meigs was a strong supporter of the Democratic Party.[7] Meigs had extremely good memory,[8] and his father instilled in him a sense of duty and a desire to pursue honorable causes.[2] Young Montgomery received schooling at the Franklin Institute[1][9] (a preparatory school for the University of Pennsylvania).[10] Meigs learned French, German, and Latin, and studied art, literature, and poetry.[11] He enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania when he was only 15 years old.[10] A hard worker, he was one of the top students at the university.[11]

The Meigs family had extensive ties to the military and to West Point, the United States Military Academy. Montgomery Meigs, caught up in the nationalistic fervor of the time, wished to serve in the army.[12] West Point was also the only engineering school in the United States at the time.[13] Through family connections,[14] Meigs won an appointment to West Point, entering in 1832.[11] He excelled in his studies at West Point, although he himself said he spent too much time at athletics and outdoor activities. He was among the top three students in French and mathematics, and did well in history.[11] He also received extensive training in drawing and map-making, which included a background in art, art history, and art theory.[15] He graduated fifth out of a class of 49 in 1836,[13] and he had more good conduct merits than two-thirds of his classmates.[11]

Early military career and engineering projects[edit]

Upon graduation from West Point, Meigs received a commission on Jul 1, 1836, as a 2d Lieutenant in the 1st U.S. Artillery. He was breveted a 2d Lieutenant in the United States Army Corps of Engineers on November 1, 1836, but the United States Department of War reverted his appointment back to the 1st Artillery on December 31. He was reappointed a brevet 2d Lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers on October 18, 1837 (after having resigned his commission in the artillery effective July 31, 1837). He was promoted to 1st Lieutenant on July 7, 1838.[16]

Meigs' first assignment, in early 1837, was to survey and make navigational improvements on the Mississippi River.[13] He served under the command of then-1st Lt. Robert E. Lee [17] He served under the command of then-1st Lieutenant Robert E. Lee.[17] Lee and Meigs were charged with two goals. The first was to improve navigation on the Mississippi River above the mouth of the Ohio River, and to save the harbor at St. Louis, Missouri. The navigational improvements were supposed to reduce the hazards associated with the Rock River Rapids, a 15-mile (24 km) stretch of rapids just north of the mouth of the Rock River, and the Des Moines Rapids, an 11-mile (18 km) section of rapids just north of the mouth of the Des Moines River.[18] The second was to alter the flow of the Mississippi River near St. Louis so that the river would no longer deposit silt and sand in front of the harbor).[19] Lee and Meigs traveled on the Pennsylvania Canal to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and then by steamboat down the Ohio River to the Mississippi. They chartered a new Corps of Engineers steamboat which was equipped with lifting equipment, and arrived in St. Louis on August 5, 1837.[20] Lee and Meigs stayed together in a hotel in St. Louis, and then later when they began surveying the lower Des Moines Rapids in an abandoned log cabin.[20] Lee and Meigs returned to St. Louis on October 8 after surveying both the Des Moines and Rock River rapids, and Meigs began drafting navigational charts of both hazards.[21] Meigs returned to Washington, D.C., with Lee in December 1837.[22] Megis and Lee worked very well together during this assignment. They established a warm friendship and maintained close social relations until 1861.[23]

From 1837 to 1839, Meigs helped build Fort Delaware and make improvements to the Delaware River. He was promoted to 1st Lieutenant on July 1, 1838. For two years beginning in 1939, he served on the Board of Engineers for the Atlantic coastal defenses. He was the supervising engineer in charge of completing Fort Delaware in 1841, and from 1841 to 1849 was the supervising engineer overseeing the construction of Fort Wayne on the Detroit River. From 1846 to 1849, he was also in charge of the construction of Fort Porter, Fort Niagara, and Fort Ontario in upstate New York state.[24] Meigs was assigned to the Engineering Bureau of the Army Corps of Engineers in Washington, D.C., in 1849, where he remained for a year on special duty as chief assistant to the Chief of Engineers, Joseph Totten.[1][25] Largely unsupervised during this period, he had extensive and direct contact with members of Congress, the Secretary of War, and the President of the United States. Historian William C. Dickinson says of this period:[26]

...Meigs proved himself to be a creative contract administrator and an excellent general manager of large and diversified design and construction work forces often numbering in the thousands. He hired and supervised talented subordinates but never left any question as to who was responsible for the project or for the expenditure of public funds. He frequently enlisted the professional advice of eminent scientists and art experts in the design and decoration of the Capitol. It is also apparent that Meigs was respected by the craftsmen and professionals whom he supervised (with the possible exception of the architect of the Capitol Thomas U. Walter) because of his continual concern for their individual welfare and the adequacy of their wages, his respect for their craftsmanship, and his reputation for impartiality and honesty.

From 1850 to 1852, Meigs was the supervising engineer overseeing the continuing construction of Fort Montgomery on Lake Champlain in New York state. He also briefly oversaw harbor improvements in Delaware Bay and along the New Jersey coast in 1852.[24]

While working on the Delaware River improvements, Meigs lived in Philadelphia near his family. It was there he met Louisa Rodgers, the daughter of Commodore John Rodgers, a naval hero of the War of 1812.[27] They married on May 2, 1841.[28] In time, the couple had seven children. Three of them—Charles Delucena (1845-1853), Vincent Trowbridge (1851-1853), and an unnamed stillborn daughter (b. 1847)—died in early childhood. Four children survived into adulthood: John Rodgers, Mary Montgomery, Montgomery Jr., and Louisa Rodgers.[25][29]

In the early 1850s, Meigs was assigned to work on the Washington Aqueduct and the extension of the United States Capitol. These were major public works: In 1856, the budget for the Capitol extension was $3.6 million and that of the aqueduct $2.3 million—about 10 percent of the total budget of the federal government. They were comparable in size to the other major national engineering projects of the day (such as the construction of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, and the Croton Aqueduct).[30] To accommodate his work on these projects, Meigs and his family moved to the District of Columbia in 1852, and Meigs would call home for the rest of his life.[6] Deeply religious, Meigs joined St. John's Episcopal Church at 16th and H Streets NW.[31] Meigs was promoted to Captain on March 3, 1853, during his work on these projects.[24]

Throughout the 1850s, Meigs cultivated close relationships with Southern Democrats in Congress, especially Jefferson Davis.[23] He was also close with Francis Preston Blair, a newspaper editor and powerful advisor in to President Andrew Jackson who helped organize the Republican Party in 1856.[32] His family's close ties to the Democratic Party also helped him during the presidential administrations of Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan.[33]

Washington Aqueduct[edit]

The Washington Aqueduct project was critical to the growth of the nation's capital. The city's population had grown from about 3,000 in 1800 to over 58,000 in 1852, and supplies of water for drinking, cooking, and fire fighting were woefully inadequate.[34] On December 24, 1851, the room in the U.S. Capitol which housed the Library of Congress was destroyed in a fire and almost spread to the Capitol's wooden dome. in early 1852 Congress allocated $5,000 to explore new sources of water. President Millard Fillmore assigned the project to Brigadier General Totten, who asked his then-chief deputy Captain Frederick Augustus Smith. But Smith died on October 16, 1852, after having just begun the project.[35] On November 3, 1852, Meigs was assigned to work on the Washington Aqueduct.[24] Meigs wrote in his private journal that he saw the aqueduct project as not only a chance to advance his career but also as a way to help the poor obtain safe drinking water and adequate fire fighting services.[6] He wrote on October 31, 1853 that the aqueduct would be "a work greater in its beneficial results than all the military glory of the Mexican War."[36] Meigs studied the water systems of Boston, London, New York City, Paris, Philadelphia, and Rome (both ancient and modern). Meigs submitted his 55-page report to Totten on February 12, 1853. Totten approved it, and after going through the appropriate political channels it was submitted to the United States Senate on February 21 (one of Fillmore's last acts as president).[37] Meigs suggested drawing on both Little Falls Branch and the Great Falls of the Potomac River for water. The centerpiece of his proposal was a 9-foot (2.7 m) wide brick-lined pipe designed to carry 67,000,000 US gallons (250,000 kl) of water a day to the city. The cost was $2 million.[38] Congress approved the project and an initial $100,000 appropriation on March 3, 1853.[39]

On March 29, 1853, the new president, Franklin Pierce, appointed Meigs supervising engineer for the aqueduct project. The same day, Pierce appointed Meigs supervising engineer of the Capitol extension project.[40] In April, Pierce ordered that all major public works in the city be carried out by the War Department and the new Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis.[41] Meigs submitted a detailed plan in June 1853, and the President and Davis approved the plan on June 28.[40] Work went slowly after the groundbreaking on October 31, 1853, in part because land had to be condemned (and Montgomery County, Maryland, lacked a sheriff to condemn land), in part because work could not occur during the malarial summer months, and in part because Congress was tardy (sometimes by months) in providing funds.[42] Representative Richard H. Stanton (D-KY) accused Meigs of improperly awarding contracts and misadministration of funds, and excoriated him on the floor of the United States House of Representatives.[43] He spent most of the spring and summer of 1856 lobbying Congress about the project, defending himself and his staff from accusations of inferior design and shoddy construction. Many members of Congress had legitimate concerns about the aqueduct, and some believed their constituents wold punish them in the next election for spending so much money on a local project. But others wanted the project taken out of the hands of the military (so they could wring patronage and pork barrel spending out of the contracts).[44]

Meigs' life during the aqueduct construction was a pleasant one. Although his salary was just $1,600 per year (which he complained of), he turned down offers to leave the Army for much more lucrative private-sector careers. He attended a large number of balls and dinner parties, and met frequently with important political figures (such as President Pierce, Commodore Matthew C. Perry, and Brigadier General Totten). He also participated in "the Club", a group of individuals who met regularly to discuss the latest developments in science and engineering. Among "the Club's" members were Joseph Henry (first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution), Alexander Dallas Bache (the physicist and surveyor who was formerly a member of the Corps of Engineers), and Captain Andrew A. Humphreys (another Corps of Engineers colleague). He also met the budding artist James Abbott McNeill Whistler, who applied for a job on the aqueduct project as a draftsman.[45]

Work on the aqueduct proceeded quickly in 1857 and 1858 due to high congressional appropriations. But work was suspended in the summer of 1859 due to a lack of money. The receiving reservoir at Little Falls Branch (now known as Dalecarlia Reservoir) had been completed in 1858, however, and it was filled while work was in abeyance. The aqueduct began providing water to the city on January 3, 1859. Meigs stood with members of Congress on the west front of the Capitol and watched as water spurted 100 feet (30 m) in the air.[46][47]

Union Arch Bridge controversy[edit]

One of Meigs' great accomplishments during construction of the Washington Aqueduct was the construction of Union Arch Bridge (better known today as Cabin John Bridge).[6] Meigs' design for the aqueduct required four aqueduct bridges, 11 tunnels, and 26 culverts. The bridge over Cabin John Creek, he said in 1853, would be at least 482 feet (147 m) in length, 101 feet (31 m) high, and 20 feet (6.1 m) wide. He proposed six arches to support the bridge. But by 1857, Meigs had modified his concept for the bridge so that it included a single 220-foot (67 m) arch.[48] Although it appears to be a single arch, the bridge has nine spandrel arches (five in the west, four in the east) atop the main arch, which are hidden from view by sandstone walls. The keystone was placed in the main arch on Decembeer 4, 1858, and the falsework beneath the main arch removed in September 1861. The bridge was complete in December 1863.[49]

There is a long-running dispute over who designed the bridge. By March 1856, Meigs had changed the basic design for the bridge from six spans to a single span.[48] In March 1857, he hired Alfred Landon Rives as assistant engineer in charge of constructing the bridge.[49] In 1877, an Army Corps of Engineers report to Congress implied that Meigs did not design the Union Arch Bridge, and that he had minimized Rives' contribution because Rives had resigned from the Corps at the start of the Civil War and joined the Confederate States Army.[50] In 1883, journalist Frank D. Carpenter alleged in Lippincott's Monthly Magazine that Rives was the sole designer of the bridge.[51] Meigs categorically denied the allegation, writing "the bridge is my sole work."[49] More recently, National Park Service historian Dean Herrin concluded in 2001 that although "Rive's contributions to the design and construction of the Cabin John Bridge were immense", "after examining all the records carefully, ample evidence exists to conclude that Meigs did originally design the Cabin John Bridge."[52] Herrin also pointed out that, in 1865, Rives had no quarrel with Meigs taking credit for the Cabin John Bridge. (Rives was only upset that Meigs had not included his name on the bridge, as he had others.)[52] In 2010, however, Dario Gasparini (an engineering professor at Case Western Reserve University) and David Simmons (a magazine editor for the Ohio Historical Society) concluded that only Rives had the technical knowledge necessary to design the bridge, and Meigs' contribution was minimal.[53]

The Cabin John Bridge was the longest single-span masonry arch bridge in the world when completed. It held this record until 1903, when the Adolphe Bridge in Luxembourg City, Luxembourg, was completed. As of 2010, it was still the longest single-span masonry arch bridge in the United States. It was designated a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Civil Engineers in 1972.[54] was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1973.[55] As of 2011, the aqueduct above the bridge still carried about 100,000,000 US gallons (380,000 kl) of water into the city every day.[6]

Meigs left the aqueduct project on September 20, 1860.[24]

U.S. Capitol extension[edit]

On March 29, 1853, Meigs was assigned to work on the U.S. Capitol extension project.[24]

Work on a Capitol extension began in 1844. Extremely poor acoustics in the House chamber and a lack of space for committees led many in Congress to suggest that a new wing be added. Representative Zadock Pratt, chair of the House Committee on Public Buildings and Grounds issued a report on May 24, 1844, in which the Army Corps of Engineers and Philadelphia architect William Strickland concluded that no existing space in the Capitol could be converted into a good speaking room. They recommended instead that a new wing be built on the south side of the building.[56] A second report issued in 1845, concluded the Capitol had too little space for committees, the Library of Congress (then housed in the Capitol) was too cramped, there was almost no storage space, the Supreme Court (also then housed in the Capitol) needed more room, and air flow (critical in an era without air conditioning) had been greatly restricted due to the construction of temporary mezzanine meeting space throughout the building.[57] The Mexican–American War of 1846-1848 prevented any further attention from being given to the problem, but in 1849 architect Robert Mills published plans to add an eastern addition to the Capitol. This appealed to many members of Congress, since it would make the United States Capitol dome appear more centered over the structure. Mills met with members of both the House and Senate throughout 1850 to push for a Capitol extension. Senators preferred wings, but House members preferred an eastern extension.[58] On September 30, 1850, President Millard Fillmore signed the Civil and Diplomatic Appropriate Bill for 1851, which approved $100,000 to draw up plans and begin construction of the extension of the Capitol. The president was authorized to appoint an architect and determine what form the extension was to take.[59]

Hiring Meigs and building the wings[edit]

In September 1850 the Senate unilaterally sponsored a design contest had attracted a large number of submissions. The House refused to consider any plans, however, arguing that the choice between eastern extension and wings had not been decided by the president. Meanwhile, architect Thomas U. Walter lobbied extensively for the job.[60] By late April 1851, President Fillmore had decided that wings were a better design concept.[61] On June 10, Fillmore appointed Thomas U. Walter architect of the Capitol extension.[62] It was an appointment designed to appease both sides: Walter was the architect favored by the House, but Walter was proposing the wing extension plan favored by the Senate.[63] With architectural plans already well-developed by Walter during his extensive lobbying for the position, the cornerstone for the extension was laid on July 4, 1851.[64] Walter came under attack from members of both the House and Senate, who accused him of mismanagement of funds, employing workers who did no work, permitting shoddy work on the foundations, and purchasing brick and marble at prices far above the market rate.[65] On December 24, 1851, a fire destroyed in the Capitol the most of the Library of Congress' holdings.[66] Walter successfully proposed building a fireproof replacement room out of iron. But again he was attacked for profligate spending and over-lavish decoration.[67] Senator Sam Houston (D-TX) chaired a special investigative committee into the alleged abuses. Houstons committee released its report on March 22, 1853, which excoriated Walter (although it cited little evidence for its claims).[68] The day after the Houston committee's report was issued, President Pierce transferred authority over the Capitol extension from the United States Department of the Interior to the War Department.[68] Pierce relied heavily on his cabinet, particularly the energetic Secretary of War Jefferson Davis,[69] and Davis encouraged Pierce to put the project in the hands of the military.[70]

One of Meigs' first tasks was to inspect the foundations, which the Houston committee believed had been improperly laid.[71] By May 1853, Meigs had finished inspecting and testing the footings, and found them sound. Meigs also conferred with Walter, and suggested moving the Senate and House chambers into the interior of each wing. Walter agreed, and Meigs designed extensive mechanical systems to provide gas lighting and ventilation systems for the extensions.[72] Meigs also ordered pediments and grand bronze doors added to the entrances in the new east porticoes.[73] The new architectural plans were submitted to the president on May 19, 1853. While they were under consideration, Meigs made a major tour of auditoriums and speaking halls in Boston, New York City, and Philadelphia to ensure that the changes to the two legislative chambers would be acoustically sound. The president approved the revised plans for the new south wing on June 27, and the for the north wing on July 5.[74]

Meigs discovered that the exterior walls were 1 to 4 inches (2.5 to 10.2 cm) too thick, and that the windowsills on the east front at least 1 inch (2.5 cm) higher in the east than the west. He began keeping a stricter watch on the construction, even as he pressed for more workers and faster delivery of materials.[75] Members of Congress began criticizing Meigs as well for excessive spending on ornamentation, especially after he ordered that the outside walls be faced with thicker marble and that the exterior columns be made of a single piece of marble rather than multiple pieces (as was usual). Nonetheless, Congress approved his contracts for these and other items on March 1, 1854.[76] Representative Richard H. Stanton continued to attack Meigs from the floor of the House, which caused a rift in Meigs' and Walter's working relationship.[77]

Among the many aspects of the Capitol extension which Meigs was responsible for designing were the skylights over each legislative chamber and the gas lighting above them.[78] Although Walter designed the cast iron door and window frames, Meigs so so impressed that he permitted them to be used throughout the extension wings. Meigs also wanted to use cast iron for the window shutters, but abandoned the idea.[78] Meigs also abandoned the idea of corrugated cast iron for roofing material, and used copper instead.[79] To assist with lifting building materials and heavy decorative elements, Meigs employed steam engines and hydraulic lifts and power drills and saws extensively on the Capitol extension and dome projects. These devices saved large amounts of money, and permitted work to continue in the hot D.C. summers.[80]

Meigs had extreme difficulty finding marble for the eastern portico columns. Meigs felt the quarry in Massachusetts which they had contracted with could not supply columns in a single piece. Floyd ordered him to investigate a quarry in Maryland, but Meigs found the quality of the marble there was poor. Meigs' superiors wanted to void the contract with the Massachusetts quarry, but President Buchanan wanted to avoid that (since the brother of the quarry owner was a powerful newspaper publisher in Pennsylvania). Visits to 17 more quarries in May and June 1859 found no better marble. Meigs suggested keeping the contract intact, but allowing the company to import marble columns from Italy.[81]

Designing and building the Capitol dome[edit]

Meigs was also intimately involved in the design and construction of the new Capitol dome. It became his favorite task.[6] Congress had discussed replacing the low wooden dome designed by William Thornton and altered and built by Charles Bulfinch, and it remains unclear who suggested that a new dome be built along with the new wings. Thomas Walter first mentioned working on a cast iron dome on May 31, 1854, and appears to have finished his design by July 20, 1854.[82] Meigs must have been involved to some degree in Walter's work, because it was Meigs who urged that the dome be built out of cast iron to save money and construction time.[6] In December 1854, as excitement for a new dome grew rapidly in Congress, Meigs began designing several domes himself. He was deeply upset when his designs did not win the excessive praise which had been heaped on Walter's design.[83] Meigs offered the House legislation on February 20, 1855, authorizing construction of the dome. When the House authorized Commissioner of Public Buildings Benjamin B. French to construct the dome, Meigs was furious. Meigs lobbied the Senate to change the legislation. The final bill, signed by the president on March 3, 1855, authorized the president to determine which agency should construct the dome.[84]

Although a new dome had been authorized at $100,000, no serious architectural work had been done on how to actually build the dome. The dome was to be 96 feet (29 m) in diameter and 300 feet (91 m) high. The dome was to sit on the existing base, but was 6 feet (1.8 m) wider than the existing base. Above the base was a peristyle of 40 columns, each 27 feet (8.2 m) high, for a total base-plus-peristyle height of 64 feet (20 m). The peristyle supported an attic 44 feet (13 m) high. The upper portion of the attic was inclined inward, and supported the dome itself (which was 56 feet (17 m) high). A tholus (or light surrounded by columns) 48 feet (15 m) high sat atop the dome, and a statue on a base (together about 21 feet (6.4 m) high) stood atop the tholus. The first problem was how to support the peristyle, which was wider that the structure below it. Thomas suggested that a new attic be built around the existing wooden dome's base, but Meigs (or his assistant engineer, Ottmar Sonnemann) came up with the idea of cantilevering the peristyle outward from the existing brickwork using iron brackets. Skirting would create a false base for appearances' sake.[85]

The second problem was how to remove the existing wooden dome. Meigs was assigned this problem on April 4, 1855.[44] Scaffolding could be erected to remove the dome's outer copper sheath and its inner plaster sheath. But a greater problem was that the floor beneath the dome was weak. Originally, an oculus existed here to provide light and ventilation to the first floor of the Capitol. But this was closed in 1838. Capitol maintenance supervisor Pringle Slight (who had closed the hole) warned Meigs about this danger.[86] But scaffolding was needed to give workers access to the dome as it rose, and some way was needed of getting materials into the air. Meigs designed a scaffold with a triangular base that avoided putting pressue on the weak spot. He also designed a steam-powered derrick with two 80-foot (24 m) wide booms capable of hoisting 20,000 pounds (9,100 kg) of construction materials into the air. He used wood stripped from the existing dome to power the steam engines running the hoist. Custom-made wire rope anchored the scaffolding to the floor.[6][86] Meigs also designed an innovative conical temporary roof to protect the interior artwork and people inside the Capitol from weather, debris, and dropped tools. Demolition of the wooden dome was complete by November 1855.[86]

Members of Congress were unhappy that the new dome was unfinished by the end of 1855 as Walter and others had promised. In April 1856, when the House began considering an appropriation to finish the dome, Meigs was blamed by many members for underestimating the cost. Meigs said he had never offered a cost estimate (Walter had).[87] The hollow iron peristyle columns, ornamental capitals and plinths for the columns, ornamented iron panels for the base, and cantilever brackets began arriving in mid-1856, and all the columns were ready for placement by November.[88]

The last remnants of the old dome came down in the fall of 1856.[89]

Decorating the Capitol[edit]

Meigs believed that Congress and Secretary of War Davis had given him great latitude on the Capitol extension project, and that this extended to the decorative aspects of the building as well.[6] He saw his mandate as making the Capitol one of the most beautiful buildings in the world. But hundreds of items—including balusters and handrails for staircases, doors and door handles, floor tiles, light fixtures, marble cornices, paintings, stained glass, and statuary—were not budgeted for.[6][90]

Meigs took action on the decorative elements of the Capitol extension as early as May 1853. That month, he ordered pediments added to the east extension entrances (on which sculptures would be added) and massive bronze doors (which he believed should rival the acclaimed Florence Baptistery bronze doors created by Lorenzo Ghiberti in 1422) for major interior and exterior entrances.[73] In July 1853, Meigs purchased a large number of art and architecture books to consult while deciding on art for the Capitol.[91] After consulting with former Senator Edward Everett (who had overseen construction of the Capitol under Charles Bulfinch), and with Jefferson Davis' support, Meigs contacted Hiram Powers and Thomas Crawford. Powers turned down the offer, but Crawford enthusiastically accepted, and by spring of 1854 had delivered a final design for Progress of Civilization for the pediment over the east Senate entrance.[92][93] In November 1854, Meigs brought decorator Emerich Carstens onto the Capitol project, and hired Ernest and Henri Thomas to provide papier-mâché ornaments (dentils, modillions, and other decorative elements).[94] Around the same time, he also hired Michigan sculptor Randolph Rogers to design bronze doors for the new main east entrance (these became the Columbus Doors) and for the bronze doors connecting the old House chamber to the corridor to the new south wing.[95] Meigs met Italian painter Constantino Brumidi on December 28, 1854, and was deeply impressed with his artwork.[96] In January 1855, he began his first work, Calling of Cincinnatus From the Plow, in the House Agriculture Committee room (occupied as of 2012 by the House Appropriations Committee). Brumidi used Meigs' own son as a model for the figure of a child gazing up from the corner. The fresco was completed in mid-March 1855.[97] Also in January 1855, Crawford began work on the bronze doors for the Senate chamber depicting scenes from the life of George Washington and the American Revolutionary War.[95] In May 1855, Meigs asked Crawford to design a statue for the top of the dome. By March 1856, after numerous revisions, Crawford's design for Freedom was finished in March 1856.253-255.</ref>

Meigs also monitored the quality of the artwork delivered. Meigs wanted to use verd antique (a green marble from Vermont) for the columns in the monumental staircases leading to the public galleries inside each wing, but not enough marble could be found.[98] Cast iron capitals for the were sculpted under Meigs' supervision and according to his design ideas, and when the capitals were delivered by the firm of Cornelius & Baker it was Meigs who asked the firm to make its more more delicate.[99] Fond of snakes as a decorative element, Meigs captured large numbers of lives snakes (including eastern rattlesnakes) during his travels to oversee work on the Washington Aqueduct and had bronze caster Federico Casali cast a dead one so that it could serve as a model for decorative elements throughout the Capitol extension.[100] Although Brumidi had provided general drawings for the balustrades and railings in the Capitol extension, Meigs peersonally oversaw both the sculptor Edmond Baudin and the foundary casting the delicate components.[101]

Meigs proved innovative in his use of materials. Meigs considered using polished marble for the floors in the extension, but most marble was committed to the exterior. After seeing an advertisement by the Minton Tile Company in September 1854, Meigs chose encaustic tile from the United Kingdom instead.[102]

Meigs' energetic pursuit of decoration for the Capitol caused a rift in his relationship with Thomas Walter. Meigs and his staff routinely made decisions which were properly Walters', and Walters believed he was often left out of decisions on which he should have been consulted. Walter also disliked Meigs' autocratic work habits, and his constant attempt to claim credit. Their relationship worsened throughout 1857.[103] Walter was unable to cultivate a relationship with the new Secretary of War, John B. Floyd, but relied on his friends in and out of Congress to speak to Floyd in his favor and to denigrate Meigs.[104]

Dismissal from the Capitol extension project[edit]

Meigs continued to come under attack in Congress throughout his tenure on the Capitol construction project. On February 13, 1854, the House established a select committee to investigate military supervision of armories, the Capitol, and customs houses. Representative Stantion chaired the select committee, and he and other members of the House used the committee to attack "military rule" over the project and Meigs as unsuited (as a military engineer) for civilian engineering work, for lax financial accounting, for ordering excessive ornamention of the extension, and for purchasing inferior building materials, among other things.[77] In spring 1856, Representative Edward Ball, chair of the Public Buildings and Grounds Committee, again accused Meigs in a lengthy report of extravagance, poor business practices, and refusing to hire American artists. Meigs fell ill with typhoid fever for five weeks, but recovered in early July.[105] Meigs replied in an extensive report which also requested an additional $2.835 million to complete the extension. Appeased, Congress gave Meigs an initial appropriation of $750,000 for the extension and $100,000 for the dome in August 1856.[106]

Walter's relationship with Meigs was also deteriorating. The two clashed extensively over whether the House chamber was ready to occupy in December 1857, and Walter began strongly criticizing what he considered gaudy and excessive decorations in the room.[107] He drafted an order which he submitted to Secretary of War Floyd in which Meigs would be completely subordinate to Walter in all design work and forced to submit any change in the extension and dome plans for authorization.[108] The two men argued publicly over the ventilation system on December 19, 1857. Meigs declared Walter unfit to make decisions about the engineering systems, and Walter accused Meigs of insubordination.[109] In a 21-page letter to Secretary of War Floyd on December 21, Walter accused Meigs of taking credit for a wide range of architectural and design decision which he had made. Meigs learned of the communication between Floyd and Walter, and altered architectural plans to bolster his own claims. Walter forced Meigs to return the documents (which he restored to their original condition), and Meigs made his case to Jefferson Davis (now back in the Senate and chair of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs).[110] When the House debated legislation to appoint a committee to supervise Meigs, Meigs accused Walter of being behind the affair (even though he was not).[111] Criticism of the adornments in the House chamber did not die down, however. An attempt to replace Meigs with an art commission (an effort partly backed by artists who had been rejected by Meigs) succeeded. In passing an appropriation to continue the extension and dome, Congress permitted the sculptural work by Crawford and Rogers to continue. President Buchanan signed the bill into law on June 12, 1858.[112]

Walter began withholding architectural drawings from Meigs in order to prevent Meigs from altering them or their authorship. Construction on the extension and dome slowed to a crawl now that drawings were unavailable. With Meigs overburdened with work on the Washingont Aqueduct and other problems, his office stopped paying bills.[111] By the end of April 1858, work on the capitol had almost stopped.[113] Even when approval for decorative elements was stripped from Meigs, Walter continued to press the War Department to have him fired.[114] Walter ordered work on the Meigs-designed rostrum for the Senate President, clerks, and reports stopped, and successfully demanded that his own design by implemented. Meigs, furious, nonetheless agreed.[115] In October 1858, Meigs demanded that Walter turn over all drawings and other papers in Walter's office, an excessive demand which Walters refused. Although the offices of the two men were close to one another, they continued to send correspondence to the Secretary of War's office, which closed completion of the Senate chamber. The Senate chamber was ready of occupancy on January 4, 1859—the day after the Wahington Aqueduct began to supply water to the city.[116] Meigs openly criticized Walter for withholding documents, overstepping his authority, and dereliction of duty in his 1858 annual report to Congress.[117]

Changes in the higher of Crawford's statue Freedom necessitated changes to the Capitol dome. Walter finished these changes on February 12, 1859. It is unlikely Meigs ever saw them. Two weeks later, when Walter submitted pay vouchers for his draftsmen, Meigs refused to sign them—infuriated that Walter had listed himself as "Architect of the New Dome".[118] An equally furious Walter appealed to Secretary of War Floyd, who ordered Meigs to pay the men. Through Floyd, Meigs and Walter sent one another scathing letters, Meigs accusing Walter of aggrandizement and Walter accusing Meigs of tyranny.[118]

Meigs also fought with Secretary of War Floyd, which eventually led to his dismissal from the project. Shortly after Floyd took office, he told Meigs that he wanted the east portico columns made of granite, or, if not, for the marble facade to be taken down and granite used. Meigs saw this as a means of awarding granite contracts to Floyd's friends in Virginia. Floyd backed off the proposal[103] But soon Meigs began fighting with Floyd over Floyd's desire to award contracts to personal friends.[119] Meigs wanted the New York company of Nason & Dodge to manufacture and install the heating working in the Capitol extension. But Floyd pressed for the contract to go to Virginia dentist Charles Robinson (who intended to sell the contract to the Baltimore firm of Henry F. Thomas & Co.). Meigs said he had ample evidence that Thomas & Co. was not qualified to do the work. The company would most likely subcontract the work, taking a commission for itself and causing the price of the contract to rise. Meigs and Floyd argued for 18 months over who should get the contract. When at last Floyd ordered Meigs to hire Thomas & Co., Meigs replied that by law he had to advertise the contract for 60 days first. Meigs also said he could not design the heating system until Walter turned over the architectural plans to him. Floyd ordered Meigs to design the heating system, and Walter volunteered to turn over any plans Meigs specified. But having seen no plans in years, and refusing to step foot in Walter's office, Meigs could not specify any plans.[120]

The dispute with Floyd came to a head in October 1859. Floyd blocked the application of John Rogers Meigs to West Point in June 1859, and Meigs met with President Buchanan over the matter. Buchanan personally approved the appointment in September.[121] Despite Floyd's order to hire Thomas & Co., Meigs asked a number of other companies to submit bids. Floyd was ill, so his chief clerk, William R. Drinkard, ordered Meigs (again) to hire Thomas & Co., and to pay a Virginia contractor for marble received for the United States Post Office building. Meigs also refused the latter order, saying that he had no idea how much marble was called for in Walter's designs for the Post Office. Meigs caustically replied on September 19 that he would not take orders from a mere clerk. When a healthy Floyd returned to the War Department, he interpreted Meigs' letter as insubordination.[122] On November 2, 1859, Meigs was removed from the Capitol extension project.[24]

Other D.C. area projects[edit]

While working on the Washington Aqueduct, Meigs was appointed by Secretary of War Jefferson Davis to be the supervising engineer on the completion of the west and north wings of the Patent Office Building in Washington,[44][70] and for the completion of Fort Madison in Annapolis, Maryland,[123][124]

The most important project, however, was the extension of the General Post Office (later known as the Tariff Commission Building). The original structure was designed by Robert Mills and constructed between 1839 and 1844. The main entrance was on E Street NW. It was 19 bays wide (about 204 feet (62 m)). Two wings, each seven bays wide, extended up 7th Street NW and 8th Street NW. The building was extended in 1855. Thomas U. Walter designed the extension, but Meigs oversaw its construction. The wings were extended to 19 bays (for a total length of 280 feet (85 m)) and a 13 bay-wide wing along F Street NW was added to complete the rectangular building. Meigs ordered construction suspended in 1861 after the outbreak of the Civil War. The building was completed in 1866.[125]

Early roles in the Civil War[edit]

Dry Tortugas[edit]

Despite his dismissal from the Capitol extension project, Meigs continued to work on the aqueduct project. Angry at his dismissal, Meigs pressed members of Congress to investigate Floyd. The congressional investigation revealed both favoritism and incompetence, and in retaliation Floyd proposed spending no money on the aqueduct in fiscal year 1859 (which commenced July 1, 1860). Meigs pointed out the omission to his friend, Senator Jefferson Davis, who not only added a $500,000 appropriation to complete the project but also included language ordering that the appropriation "be expended according to the plans and estimates of Captain Meigs, and under his superintendence..."[126] The House of Representatives agreed to the language, and Buchanan signed the bill on June 25, 1860.[127]

Buchanan, deeply insulted by the legislation, appointed Captain Henry Washington Benham chief engineer of the aqueduct project, and ordered Meigs to be his disbursing officer in order to comply with the legislation. Meigs wrote a lengthy letter to Buchanan protesting the assignment, especially since Congress in 1806 had specifically outlawed the use of military engineers to duties outside their profession. Buchanan referred the letter to the United States Department of Justice to determine if it was insubordinate, but it was found not to be. When Meigs refused to pay an inspector whom Benham had hired, Floyd issued an order on September 18, 1860, removing Meigs from the aqueduct project and ordering him to report to Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas—a small group of islands located at the end of the Florida Keys.[128]

Meigs departed for the Dry Tortugas on October 22, and arrived on November 8. On the way, he visited Lynchburg, Virginia; Knoxville, Tennessee; Columbus, Georgia; Montgomery, Alabama; Pensacola, Florida; and Key West, Florida.[129] On his trip, Meigs took notes about the forts he saw along the way, and reported to Commanding General Winfield Scott on November 10 that the forst could be held if supplied with enough men loyal to the Union.[130] Floyd's resignation at the end of December 1860 and the efforts of friends in and out of Congress (particularly the powerful Republican Party activist Francis Preston Blair) led to efforts to return Megis to Washington. On January 20, 1861, he was ordered to return to the aqueduct project. He arrived in the city on February 20.[131]

Changing political beliefs[edit]

Prior to the presidential election of November 1860, Meigs had been determinedly apolitical. When his father asked him to join the Democratic Party in 1840, Meigs declined. He wrote back that it was improper for an employee of the federal government to be involved in politics.[32] When family members and friends pressed Meigs to join the Democratic Party out of allegiance to the state of Georgia, Meigs declared:[32]

I am a citizen of the United States, not of Connecticut where my grandfather lived or of Georgia where I was born or of Pennsylvania where I was educated. I should as soon think of boasting of being an Arch Streeter or a Chestnut Streeter as a Pennsylvanian or Georgian.

By 1860, however, Meigs had begun to take sides in the great political debates which were about to sunder the Union. He came to deeply loathe slavery, and believed that the Civil War was punishment for tolerating it. "God for our sins leads us to [victory] through seas of blood," he later wrote to his son, John.[6] Meigs voted for Senator Stephen A. Douglas in the 1860 presidential election.[132]

By March 1861, however, Meigs was a staunch Lincoln supporter. The catalyst for his change in views came during Lincoln's inauguration. Meigs was certain that Lincoln was ill-equipped to lead a nation heading toward civil war. Meigs attended Lincoln's inaugural on March 4, 1861. Lincoln's inaugural address completely changed his views of the president. Meigs became a fervent believer in the leadership skill and wisdom of Abraham Lincoln.[133]

Southern coastal forts mission[edit]

After Meigs' return to the city, he quickly moved to re-establish control over both the Washington Aqueduct and Capitol extension projects. The new Secretary of War, Joseph Holt, reappointed Meigs to both positions. Captain Franklin was assigned to supervise construction of the west wing of the Treasury Building. Meigs tried to fire Walter on March 2. Walter informed him that as a presidential appointee, only the president could fire him. On March 5, Abraham Lincoln's Secretary of War, Simon Cameron, affirmed that Walter should remain as architect of the Capitol. But Cameron also made it clear that Walter was to be Meigs' subordinate.[134]

Meigs' role in the war changed dramatically on March 29.[135] The Lincoln administration was debating whether to try to hold Fort Sumter in South Carolina and Fort Pickens off Pensacola, Florida. Lincoln wished to hear from an officer who had been in the field, and Secretary of State William H. Seward brought Meigs to a secret meeting with the president. Meigs said both forts could be held if provisioned and garrisoned, and suggested that the USS Powhatan (recently returned from an overseas mission) be used. Lincoln said he would consider the proposal, and on March 31 summoned Meigs and Lieutenant Colonel Erasmus D. Keyes to the White House to hear more detailed plans. Lincoln approved the mission. Provisioned with $10,000, Meigs traveled to New York City. The Powhatan sailed for Ft. Pickens on April 6, followed by Meigs on April 7 aboard the SS Atlantic. Ft. Pickens was successfully reinforced on April 20.[136] Meigs returned to New York on May 1.[137]

Ft. Pickens remained in Union hands for the rest of the war.[138] Francis Preston Blair later wrote of Meigs' decisive advice and action, "They sent Meigs to gather a thistle, but thank God, he has plucked a laurel."[6]

Later Civil War roles[edit]

On May 14, 1861, Meigs was appointed colonel, 11th U.S. Infantry, and on the following day, promoted to brigadier general and Quartermaster General of the Army. The previous Quartermaster General, Joseph Johnston, had resigned and become a general in the Confederate Army. Meigs established a reputation for being efficient, hard-driving, and scrupulously honest. He molded a large and somewhat diffuse department into a great tool of war. He was one of the first to fully appreciate the importance of logistical preparations in military planning, and under his leadership, supplies moved forward and troops were transported over long distances with ever-greater efficiency.

Lincoln routinely visited Meigs, who was one of his most trustworthy subordinates. Lincoln often found inspiration and renewed hope when talking with Meigs. [133]

Of his work in the quartermaster's office, James G. Blaine remarked:

"Montgomery C. Meigs, one of the ablest graduates of the Military Academy, was kept from the command of troops by the inestimably important services he performed as Quartermaster General. Perhaps in the military history of the world there never was so large an amount of money disbursed upon the order of a single man ... The aggregate sum could not have been less during the war than fifteen hundred million dollars, accurately vouched and accounted for to the last cent."

Secretary of State William H. Seward's estimate was "that without the services of this eminent soldier the national cause must have been lost or deeply imperiled."

Meigs' services during the Civil War included command of Lietenant General Ulysses S. Grant's base of supplies at Fredericksburg and Belle Plain, Virginia (1864); command of a division of War Department employees in the defense of Washington at the time of Jubal A. Early's raid (July 11 to 14, 1864); personally supervising the refitting and supplying of Major General William T. Sherman's army at Savannah (January 5 to 29, 1865), Goldsboro, and Raleigh, North Carolina and reopening Sherman's lines of supply (March to April 1865). He was brevetted to major general on July 5, 1864.

The refit of Sherman’s army at Savannah in 1864 was regarded by Meigs as one of his finest moments during the war and “perhaps the greatest of all the accomplishments of the quartermaster fleet,” according to historian Russell Weigley’s book, “Quartermaster General of the Union Army.” [6]

George Templeton Strong called him "an exceptional and refreshing specimen of sense and promptitude, unlike most of our high officials. There's not a fibre of red tape in his constitution." In December 1861, the New York Tribune said glowingly of Meigs "A new and most efficient head, by the best fortune in the owrld, was given to the Quartermaster's Department." several historians, most notably Allan Nevins and Russell Weigley, called him one of the most important leaders in the Civil War. [119]

During the war, Meigs was so highly regarded that almost anyone who mattered listened to him. Upon receiving one report from Meigs, whose script was notoriously illegible, an admiring Sherman said: “The handwriting of this report is that of General Meigs, and I therefore approve of it, but I cannot read it.” [6]

Lincoln expressed unalloyed admiration for him. “I have come to know [Meigs] quite well for a short acquaintance, and so far as I am capable of judging I do not know one who combines the qualities of masculine intellect, learning and experience of the right sort, and physical power of labor and endurance so well as he.” Despite his lack of battlefield experience, Meigs became one of Lincoln’s trusted wartime advisers. [6]

Meigs may be the most important bureaucrat in American history, a desk jockey who built the war machine that crushed the Confederacy. [6]

A staunch Unionist despite his Southern roots, Meigs detested the Confederacy.

Meigs later wrote glowing things about Lee, but only long after Lee was dead [20]

His feelings led directly to the establishment of Arlington National Cemetery. On July 16, 1862, Congress passed legislation authorizing the U.S. federal government to purchase land for national cemeteries for military dead, and put the U.S. Army Quartermaster General in charge of this program. The Soldiers' Home in Washington, D.C., and the Alexandria Cemetery were the primary burying grounds for war dead in the D.C. area, but by late 1863 both cemeteries were full.[139] In May 1864, Union forces suffered large numbers of dead in the Battle of the Wilderness. Meigs ordered that an examination of eligible sites be made for the establishment for a large new national military cemetery. Within weeks, his staff reported that Arlington Estate was the most suitable property in the area.[139] The property was high and free from floods (which might unearth graves), it had a view of the District of Columbia, and it was aesthetically pleasing. It was also the home of the leader of the armed forces of the Confederate States of America, and denying Robert E. Lee use of his home after the war was a valuable political consideration.[140] Although the first military burial at Arlington had been made on May 13,[141] Meigs did not authorize establishment of burials until June 15, 1864.[142] Meigs ordered that the estate be surveyed and that 200 acres (81 ha) be set aside for use as a cemetery.[142]

In October 1864, his son, 1st Lieutenant John Rodgers Meigs, was killed at Swift Run Gap in Virginia and was buried at a Georgetown Cemetery.[143] Lt. Meigs was part of a three-man patrol which ran into a three-man Confederate patrol. Lt. Meigs was killed, one man was captured, and one man escaped. To the end of his life, Meigs believed that his son had been murdered after being captured—despite evidence to the contrary.[144] The younger Meigs was laid to rest in Oak Hill Cemetery in Georgetown in Washington, D.C. Both Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton attended the interment.[145]

Meigs also played a role in the death of Abraham Lincoln. At 10:00 P.M. on the evening of April 14, 1865, Meigs heard that William Seward had been attacked by a knife-wielding assailant. Meigs rushed to Rodgers House, Seward's home on Lafayette Square just across the street from the White House.[146] Shortly after arriving at Seward's home, Meigs learned of the assassination of Lincoln. He rushed to the Petersen House across from Ford's Theatre, where Lincoln lay dying. Meigs stood at the front door of the house for the rest of the deathwatch. He alone decided who was admitted to the house. When Lincoln died at 7:22 A.M. on April 15, Meigs moved into the parlor to sit with the president's body. During Lincoln's funeral procession in the city five days later, Meigs rode at the head of two battalions of quartermaster corps soldiers.[147]

Role in developing Arlington National Cemetery[edit]

Meigs played a critical role in developing Arlington National Cemetery, both during the Civil War and afterward.

Although most burials initially occurred near the freedmen's cemetery in the estate's northeast corner, in mid-June 1864 Meigs ordered that burials commence immediately on the grounds of Arlington House. Brigadier General René Edward De Russy was living in Arlington House at the time and opposed the burial of bodies close to his quarters, forcing new interments to occur far to the west (in what is now Section 1 of the cemetery). But Meigs still demanded that officers be buried on the grounds of the mansion, around the Lee's former flower garden. The first officer burial had occurred there on May 17, but with Meigs' order another 44 officers were buried along the southern and eastern sides within a month. By May 31, more than 2,600 burials had occurred in the cemetery, and Meigs ordered that a white picket fence be constructed around the burial grounds.[141] In December 1865, Robert E. Lee's brother, Smith Lee, visited Arlington House and observed that the house could be made livable again if the graves around the flower garden were removed.[148] Meigs hated Lee for betraying the Union,[149] and ordered that more burials occur near the house in order to make it politically impossible for disinterment to occur.[150]

Meigs himself designed and implemented most of the changes at the cemetery in the 15 years after the war.[151] In 1865, for example, Meigs decided to build a monument to Civil War dead in the center of a grove of trees west of the Lee's flower garden.[152] U.S. Army troops were dispatched to investigate every battlefield within a 35-mile (56 km) radius of the city of Washington, D.C. The bodies of 2,111 Union and Confederate dead were collected, most of them from the battlefields of First and Second Bull Run as well as the Union army's retreat alone the Rappahannock River (which occurred after both battles). Although Meigs had not intended to collect the remains of Confederate war dead, the inability to identify remains meant that both Union and Confederate dead were interred below the cenotaph.[153] U.S. Army engineers chopped down most the trees and dug a circular pit about 20-foot (6.1 m) wide and 20-foot (6.1 m) deep into the earth.[154] The walls and floor were lined with brick, and it was segmented it into compartments with mortared brick walls.[152] Into each compartment were placed a different body part: skulls, legs, arms, ribs, etc.[155] The vault was half full by the time it was ready for sealing in September 1866.[152] Meigs designed[156] a 6-foot (1.8 m) tall, 12-foot (3.7 m) long, 4-foot (1.2 m) wide grey granite and concrete cenotaph to rest on top of the burial vault. The Civil War Unknowns Monument consists of two long light grey granite slabs, with the shorter ends formed by sandwiching a smaller slab between the longer two. On the west face was an inscription describing the number of dead in the vault below, and honoring the "unknowns of the Civil War".[152] Originally, a Rodman gun was placed on each corner, and a pyramid of shot adorned the center of the lid. A circular walk, centered 45 feet (14 m) from the center of the memorial, provided access. A walk led east to the flower garden, and another west to the road. Sod was laid around the memorial, and planting beds filled with annual plants emplaced.[152]

Meigs made additional major changes to the cemetery in the 1870s. In 1870, he ordered that a "Sylvan Hall"—a series of three cruciform tree plantings, one inside the other—be planted in the "Field of the Dead" (in what is now Section 13).[157] A year later, Meigs ordered the McClellan Gate constructed. Located just west of the intersection of what is today McClellan and Eisenhower Drives, this was originally Arlington National Cemetery's main gate. Built of red sandstone and red brick, the name "MCCLELLAN" tops the simple rectangular gate in gilt letters. But just below the name was inscribed the name "MEIGS"—a tribute to himself which Meigs could not help making.[158][159] Due to the growing importance of the cemetery as well as the much larger crowds attending Memorial Day observances, Meigs also decided a formal meeting space at the cemetery was needed.[160] A grove of trees southwest of Arlington House was cut down, and an amphitheater (today known as the Old Amphitheater) was constructed in 1874.[161] Meigs himself designed the rostrum for the amphitheater.[158]

Meigs continued to work to ensure that the Lee family could never take control of Arlington. In 1882, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in United States v. Lee that the seizure of the Arlington estate at a tax sale by the United States was illegal, and returned the estate to George Washington Custis Lee, General Lee's oldest son.[162] He, in turn, sold the estate back to the U.S. government for $150,000 in 1883.[163] To commemorate the retention of the estate, in 1884 Meigs ordered that a Temple of Fame be erected in the Lee flower garden.[164] The U.S. Patent Office building had suffered a massive fire in 1877. It was torn down and rebuilt in 1879, but the work went very slowly. Meigs ordered that stone columns, pediments, and entablatures which had been saved from the Patent Office be used to construct the Temple of Fame. The Temple was a round, Greek Revival, temple-like structure with Doric columns supporting a central dome. Inscribed on the pediment supporting the dome were the names of great Americans such as George Washington, Ulysses S. Grant, Abraham Lincoln, and David Farragut. A year after it was built, the names of Union Civil War generals were carved into its columns.[165] Since there wasn't enough marble to rebuild the dome, a tin dome (molded and painted to look like marble) was installed instead.

Postbellum career and death[edit]

Meigs became a permanent resident of the District of Columbia after the war. He purchased a home located at 1239 Vermont Avenue NW (at the corner of Vermont Avenue and N Street).

As Quartermaster General after the Civil War, Meigs supervised plans for the new War Department building (constructed between 1866 and 1867), the National Museum (constructed in 1876), the extension of the Washington Aqueduct (constructed in 1876), and for a hall of records (constructed in 1878). Along with fellow Quartermaster Brigadier General Roeliff Brinkerhoff, Meigs edited a volume entitled, The Volunteer Quartermaster, a treatise which was considered the standard guide for the officers and employees of the quartermaster's department up until the World War I.[166]

From 1866 to 1868, to recuperate from the strain of his war service, Meigs visited Europe, and from 1875 to 1876 made another visit to study the organization of European armies. After his retirement on February 6, 1882, he became architect of the Pension Office Building, now home to the National Building Museum. He was a regent of the Smithsonian Institution, a member of the American Philosophical Society, and one of the earliest members of the National Academy of Sciences.

Both Meigs and Cluss served on the three-person commission established to determine the cause of the 1877 fire in the Patent Office. Adolf Cluss, architect : from Germany to America Author: Alan Lessoff; Christof Mauch; Charles Sumner school museum and archives (Washington, D.C.); Heilbronn (Allemagne). Stadtarchiv. Publisher: [Washington (D.C.)] : Historical Society of Washington ; [Heilbronn] : Stadtarchiv Heilbronn ; New York : In association with Berghahn Books, cop. 2005. 140

Pension Building[edit]

the Pension Building, designed by Montgomery Meigs in 1882

Following the end of the Civil War, the United States Congress passed legislation that greatly extended the scope of pension coverage for both veterans and for their survivors and dependents, notably their widows and orphans. This greatly increased the number of staff needed to administer the new benefits system. More than 1,500 clerks were required, and a new building needed to house them. Meigs was chosen to design and construct the new building, now the National Building Museum. He broke away from the established Greco-Roman models that had been the basis of government buildings in Washington, D.C., up until then, and was to continue following the completion of the Pension Building. Meigs based his design on Italian Renaissance precedents, notably Rome's Palazzo Farnese and Plazzo della Cancelleria.

Included in his design was a 1,200-foot (370 m) long sculptured frieze executed by Caspar Buberl. Since creating a work of sculpture of that size was well out of Meigs's budget, he had Buberl create 28 different scenes (totaling 69 feet (21 m) in length), which were then mixed and slightly modified to create the continuous 1,200-foot (370 m) long parade that includes over 1,300 figures. Because of the way that the 28 sections are modified and mixed up, it is only by somewhat careful examination that the frieze reveals itself to be the same figures repeated over and over. The sculpture includes infantry, navy, artillery, cavalry, and medical components as well as a good deal of the supply and quartermaster functions. Meigs's correspondence with Buberl reveals that Meigs insisted that one teamster, "must be a negro, a plantation slave, freed by war," be included in the Quartermaster panel.[167] This figure was ultimately to assume a position in the center, over the west entrance to the building.

When Philip Sheridan was asked to comment on the building, his reply echoed the sentiment of much of the Washington establishment of the day, that the only thing that he could find wrong with the building was that it was fireproof. (A similar quote is also attributed to William T. Sherman, so the story might well be apocryphal.) The completed building, sometimes referred to as "Meigs's Old Red Barn", was created by using more than 15,000,000 bricks,[168] which, according to the wits of the day, were all counted by the parsimonious Meigs.

The result was big, brash and controversial, an expensive structure made with more than 15 million red bricks that mixed the classical with the modern. At the time, some critics derided the building as an aesthetic catastrophe, calling it Meigs’s “Old Red Barn.” Sherman is said to have cracked that the building was fine but for one thing: “It’s too bad the damn thing is fireproof.” Some people now consider it among the most beautiful, venerable buildings in Washington. It’s the National Building Museum. Meigs, who so wanted to be remembered, would be proud. [6]

Death[edit]

Meigs contracted a cold on December 27, 1891. Within a few days, it turned into pneumonia. Meigs died at home at 5:00 P.M. on January 2, 1892.[169] His body was interred with high military honors in Arlington National Cemetery. General orders issued at the time of his death declared that "the Army has rarely possessed an officer ... who was entrusted by the government with a great variety of weighty responsibilities, or who proved himself more worthy of confidence."[170]

Honors[edit]

- General Meigs was inducted into the Quartermaster Hall of Fame in its charter year of 1986.

- USAT Meigs, an Army transport ship sunk at Darwin, Northern Territory, was named in his honor.

- The transport USS General M. C. Meigs (AP-116), launched in 1944, was named in his honor.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Hannan, p. 140.

- ^ a b Ferguson, p. 52.

- ^ a b "General Montgomery Cunningham Meigs." Scientific American. January 30, 1892, p. 71. Accessed 2012-12-15.

- ^ Browning, p. 239-240. Accessed 2012-12-15.

- ^ Morton, p. 508. Accessed 2012-12-15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q O'Harrow, Jr., Robert. "Montgomery Meigs's Vital Influence on the Civil War — and Washington." Washington Post. July 1, 2011. Accessed 2012-12-16.

- ^ Wilson, p. 42.

- ^ Field, p. 73.

- ^ "Obituary: Gen. Montgomery C. Meigs." Public Opinion. January 9, 1892, p. 321. Accessed 2012-12-15.

- ^ a b Miller, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e Field, p. 74.

- ^ Weigley, p. 23.

- ^ a b c Herrin, p. 4.

- ^ Wilson p. 41-42.

- ^ Wolanin, p. 134-137.

- ^ Cullum, Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., from March 16, 1802, to January 1, 1850, p. 207. Accessed 2012-12-15.

- ^ a b Ulbrich, p. 1312; Freeman, p. 140-47.

- ^ Thomas, p. 86.

- ^ Thomas, p. 86-87.

- ^ a b c Thomas, p. 87.

- ^ Thomas, p. 89.

- ^ Thomas, p. 92.

- ^ a b Gaughan, p. 32.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cullum, Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N. Y., From Its Establishment in 1802 to 1890, p. 631. Accessed 2012-12-15.

- ^ a b Giunta, p. 1.

- ^ Dickinson, p. 171-172.

- ^ Schama, p. 61.

- ^ Lee, p. 30, fn. 3.

- ^ Meigs, p. 88. Accessed 2012-12-15.

- ^ Dickinson, p. 174.

- ^ Dickinson, p. 170.

- ^ a b c Wilson, p. 63.

- ^ Dickinson, p. 171.

- ^ Ways, p. 21.

- ^ Ways, p. 21-22.

- ^ Ways, p. 27.

- ^ Ways, p. 22.

- ^ Ways, p. 22-23.

- ^ Ways, p. 23-24.

- ^ a b Ways, p. 24.

- ^ Allen, p. 211.

- ^ Ways, p. 28-29.

- ^ Ways, p. 29.

- ^ a b c Ways, p. 33.

- ^ Ways, p. 32-33.

- ^ Ways, p. 34.

- ^ Author Guy Gugliotta claims Meigs' fountain is today the West Front Fountain. See Gugliotta, p. 320. However, the West Front Fountain was built in 1888 atop an existing drinking fountain installed by Robert Mills in 1834. See Allen, p. 357-358. Pictorial evidence indicates that Meigs' fountain was located west of the new Senate extension, about halfway between the Senate wing and what is now Peace Circle. See Ways, p. 36, fig. 9.

- ^ a b Ways, p. 39.

- ^ a b c Ways, p. 40.

- ^ "Report of Colonel O.E. Babcock, Corps of Engineers." Annual Report of the Secretary of War. Appendix KK. Vol. 2. United States Department of War. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1877, p. 1097-1098. Accessed 2012-12-17.

- ^ Carpenter, Frank D. Y. "Government Engineers." Lippincott's Monthly Magazine. August 1883, p. 159-168. Accessed 2012-12-17.

- ^ a b Herrin, p.17.

- ^ Gasparini and Simmons, p. 188–203.

- ^ Gasparini and Simmons, p. 188.

- ^ "Cabin John Aqueduct." NHRP No. 73000932. Inventory Nomination Form for Federal Properties. Form No. 10-306 (Rev. 10-74). National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. February 28, 1973. Note that this NHRP designation is listed as "Cabin John Aqueduct" and refers to the bridge. There is a separate NRHP designation for the Washington Aqueduct which refers to the entire aqueduct system from Great Falls, Maryland, to Washington, D.C.

- ^ Allen, p. 180.

- ^ Allen, p. 180-181.

- ^ Allen, p. 181-185.

- ^ Allen, p. 185.

- ^ Allen, p. 187-195.

- ^ Allen, p. 194.

- ^ Allen, p. 195.

- ^ Allen, p. 196.

- ^ Allen, p. 199.

- ^ Allen, p. 202-205.

- ^ A fire had been laid in a fireplace in the room below the Library of Congress room. The chimney flue ran between the walls to the roof. Soot in the flue caught fire, and a chink in the chimney permitted the fire to ignite wooden shelving in a library alcove. See: Allen, p. 206.

- ^ Allen, p. 207-211.

- ^ a b Allen, p. 213.

- ^ Allen, p. 207.

- ^ a b Allen, p. 215.

- ^ Allen, p. 215-216.

- ^ Allen, p. 217-218.

- ^ a b Allen, p. 218-219.

- ^ Allen, p. 219.

- ^ Allen, p. 219-222.

- ^ Allen, p. 222-223.

- ^ a b Allen, p. 223-225.

- ^ a b Allen, p. 242.

- ^ Allen, p. 244.

- ^ Allen, p. 243-244.

- ^ Allen, p. 290.

- ^ Allen, p. 225.

- ^ Allen, p. 227-229.

- ^ Allen, p. 229-230.

- ^ Allen, p. 203. The number of columns in the peristyle was reduced from 40 to 36, to make it simpler to evenly distribute them around the dome.

- ^ a b c Allen, p. 233.

- ^ Allen, p. 234-236.

- ^ Allen, p. 237.

- ^ Allen, p. 258.

- ^ Allen, p. 238.

- ^ Allen, p. 246-247.

- ^ Allen, p. 245-246.

- ^ Although numerous sculptores interviewed and provided designs for the southern pediment, no design was chosen. A sculptural group, Apotheosis of Democracy by Paul Wayland Bartlett would not be added until 1916. See: Allen, p. 252-253.

- ^ Allen, p. 247-248.

- ^ a b Allen, p. 249.

- ^ Allen, p. 228.

- ^ Allen, p. 250-252.

- ^ Brown Tennessee marble was used instead, to Walter's delight. See: Allen, p. 240.

- ^ Allen, p. 238-239.

- ^ Allen, p. 250.

- ^ Allen, p. 278.

- ^ Allen, p. 241-242.

- ^ a b Allen, p. 267.

- ^ Allen, p. 268.

- ^ Allen, p. 256-257.

- ^ Allen, p. 257.

- ^ Allen, p. 268-271.

- ^ Allen, p. 271-272.

- ^ Allen, p. 272.

- ^ Allen, p. 272-275.

- ^ a b Allen, p. 276.

- ^ Allen, p. 279-281.

- ^ Allen, p. 277.

- ^ Allen, p. 281-283.

- ^ Allen, p. 283.

- ^ Allen, p. 283-285.

- ^ Allen, p. 287.

- ^ a b Allen, p. 289-290.

- ^ a b Wilson, p. 64.

- ^ Allen, p. 292-293.

- ^ Miller, p. 39.

- ^ Allen, p. 293.

- ^ Giunta, p. 35, fn. 1.

- ^ Robert Mills and William Eliot designed the Patent Office Building, although Mills oversaw its construction. Mills was ousted from the project in 1851, having completed only the south and east wings. Thomas U. Walter designed the north and west wings. See: Moeller, p. 89-90.

- ^ "Tariff Commission Building." NHRP No. 69000311. Inventory Nomination Form for Federal Properties. Form No. 10-300. National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. March 24, 1969. Accessed 2012-12-17.

- ^ Miller, p. 58-59, quoted on p. 59.

- ^ Miller, p. 59.

- ^ Miller, p. 59-62.

- ^ Miller, p. 70.

- ^ Miller, p. 72.

- ^ Miller, p. 73-74.

- ^ Wilson, p. 63-64.

- ^ a b White, p. 464.

- ^ Miller, p. 77-79.

- ^ Gugliotta, p. 376.

- ^ Miller, p. 84-86.

- ^ Miller, p. 89.

- ^ Miller, p. 88.

- ^ a b Cultural Landscape Program, p. 84. Accessed 2012-05-03.

- ^ Cultural Landscape Program, p. 88. Accessed 2012-05-03.

- ^ a b Cultural Landscape Program, p. 86. Accessed 2012-05-03.

- ^ a b Cultural Landscape Program, p. 85. Accessed 2012-05-03.

- ^ Poole, p. 64.

- ^ Miller, p. 241-242.

- ^ Schama, p. 104.

- ^ Bednar, p. 99.

- ^ Schama, p. 105.

- ^ Cultural Landscape Program, p. 87. Accessed 2012-05-03.

- ^ Peters, p. 142.

- ^ Poole, Robert M. "How Arlington National Cemetery Came to Be." Smithsonian Magazine. November 2009. Accessed 2012-04-29.

- ^ Cultural Landscape Program, p. 103. Accessed 2012-05-03.

- ^ a b c d e Cultural Landscape Program, p. 96. Accessed 2012-04-29.

- ^ Heidler, Heidler, and Coles, p. 78.

- ^ Poole, p. 86.

- ^ Bigler, p. 30.

- ^ Poole, p. 87.

- ^ Cultural Landscape Program, p. 103. Accessed 2012-05-03

- ^ a b Poole, p. 89.

- ^ Hughes and Ware, p. 65.

- ^ Cultural Landscape Program, p. 107-108. Accessed 2012-05-03

- ^ Cultural Landscape Program, p. 108. Accessed 2012-05-03.

- ^ Poole, 2009, p. 55.

- ^ Atkinson, 2007, p. 26; Holt, 2010, p. 336.

- ^ Poole, p. 167.

- ^ Cultural Landscape Program, p. 122. Accessed 2012-05-03.

- ^ General Roeliff Brinkerhoff. Ohio History: The Scholarly Journal of the Ohio Historical Society. Volume 20.

- ^ Jacob, p. 67.

- ^ Building Museum Website retrieved 27 June 2010

- ^ "Death of Gen. Meigs." Washington Post. January 3, 1892.

- ^ Fawell, p. 458.

Bibliography[edit]

- Allen, William Charles. History of the United States Capitol: A Chronicle of Design, Construction, and Politics. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2001.

- Atkinson, Rick. Where Valor Rests: Arlington National Cemetery. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society, 2007.

- Bednar, Michael J. L' Enfant's Legacy: Public Open Spaces in Washington, D.C. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

- Browning, Charles Henry. Americans of Royal Descent. Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing, 1911.

- Cultural Landscape Program. Arlington House: The Robert E. Lee Memorial Cultural Landscape Report. National Capital Region. National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Washington, D.C.: 2001.

- Cullum, George W. Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N. Y., From Its Establishment in 1802 to 1890. Vol. 1. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1891.

- Cullum, George W. Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., from March 16, 1802, to January 1, 1850. New York: J.F. Trow, 1850.

- Dickinson, William C. "Montgomery C. Meigs, the New Age Public Manager." In Montgomery C. Meigs and the Building of the Nation's Capital. William C. Dickinson, Dean A Herrin, and Donald R Kennon, eds. Athens, Ohio: United States Capitol Historical Society, 2001.

- Eicher, John H. and Eicher, David J. Civil War High Commands. Palo Alto, Calif: Stanford University Press, 2001.

- Farwell, Byron. The Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Land Warfare. New York: Norton, 2001.

- Field, Cynthia R. "A Rich Repast of Classicism: Meigs and Classical Sources." In Montgomery C. Meigs and the Building of the Nation's Capital. William C. Dickinson, Dean A. Herrin, and Donald R. Kennon, eds. Athens, Ohio: United States Capitol Historical Society, 2001.

- Freeman, Douglas S. R. E. Lee, A Biography. 4 vols. New York: Scribners, 1934.

- Gasparini, Dario A. and Simmons, David A. "Cabin John Bridge: Role of Alfred L. Rives, C.E." Journal of Performance of Constructed Facilities. 24:2 (2010): 188–203.

- Gaughan, Anthony J. The Last Battle of the Civil War: United States versus Lee, 1861-1883. Baton Rouge, La.: Louisiana State University Press, 2011.

- Giunta, Mary A. "Introduction." In A Civil War Soldier of Christ and Country: The Selected Correspondence of John Rodgers Meigs, 1859-64. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 2006.

- Gugliotta, Guy. Freedom's Cap: The United States Capitol and the Coming of the Civil War. New York: Hill and Wang, 2012.