User:Tim riley/sandbox

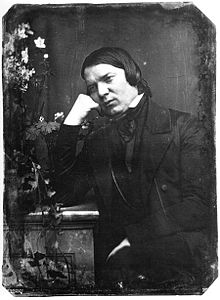

Robert Schumann[n 1] (German: [ˈʁoːbɛʁt ˈʃuːman]; 8 June 1810 – 29 July 1856) was a German composer, pianist, and music critic of the Romantic era.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Praesent maximus egestas urna sed auctor. Mauris ipsum nisl, dignissim tristique nisi et, iaculis placerat nunc. Suspendisse ut dictum augue. Vestibulum fringilla, neque eu finibus elementum, dui neque iaculis leo, eget congue ligula ipsum a lorem. Donec id tincidunt nibh, sed semper odio. Cras imperdiet, ligula ac efficitur dignissim, risus elit mattis lorem, quis aliquet arcu justo ac leo. Curabitur posuere aliquam elit, vitae pellentesque ex commodo vel. Sed laoreet vehicula ultricies. Aenean nec fringilla sapien. Duis eu mi vitae arcu tincidunt rhoncus euismod vitae augue. Morbi faucibus lectus vel erat aliquet ultrices. In ut finibus orci.

Maecenas sed fermentum lacus. Morbi at viverra ante. Cras posuere faucibus nisi, non ultrices purus fringilla vel. Phasellus tortor magna, dapibus id gravida a, fringilla ut mauris. Aliquam laoreet purus sapien, at accumsan nulla mattis non. Maecenas volutpat nibh eros, at pulvinar arcu lobortis id. Integer quis vulputate dolor, ac condimentum ligula. Etiam id turpis lorem. Duis sollicitudin placerat lacus sed egestas. Cras quis eros a enim tristique facilisis. In mauris ipsum, finibus non nunc ut, congue blandit lacus. Donec sodales justo pellentesque tellus ultricies, et malesuada arcu tempor.

Curabitur rutrum eros a interdum efficitur. Pellentesque habitant morbi tristique senectus et netus et malesuada fames ac turpis egestas. Vestibulum at metus vitae turpis egestas faucibus. Fusce semper est vitae eros efficitur rutrum. Suspendisse interdum suscipit erat id cursus. Pellentesque sit amet nisi non augue viverra laoreet. Cras vitae mattis velit. Integer sit amet placerat massa. Aliquam laoreet purus sapien, at accumsan nulla mattis non. Maecenas volutpat nibh eros, at pulvinar arcu lobortis id. Integer quis vulputate dolor, ac condimentum ligula. Etiam id turpis lorem. Duis id tempus neque. Donec in molestie nisi. Donec interdum luctus erat et ullamcorper. Nullam eleifend mi scelerisque sodales mollis. Proin sit amet tortor a ex pretium imperdiet quis et ante. Duis mattis ex tortor, quis mattis lacus tristique a. Fusce rutrum eleifend elit eget consectetur.

Life and career[edit]

Childhood[edit]

Robert Schumann[n 1] was born in Zwickau, in the Kingdom of Saxony (today the state of Saxony), into an affluent middle class family.[4] On 13 June 1830 the local newspaper, the Zwickauer Wochenblatt (Zwickau Weekly Paper), carried the announcement, "On 8 June to Herr August Schumann, notable citizen and bookseller here, a little son".[5] He was the fifth and last child of August Schumann and his wife, Johanna Christiane (née Schnabel). August, not only a bookseller but also a lexicographer, author and publisher of chivalric romances, made considerable sums from his German translations of writers such as Cervantes, Walter Scott and Lord Byron.[2] Robert, his favourite child, was able to spend many hours exploring the classics of literature in his father's collection.[2] Intermittently, between the ages of three and five-and-a-half, he was placed with foster parents, as his mother had contracted typhus.[4]

At the age of six Schumann went to a private preparatory school, where he remained for four years.[6] When he was seven he began studying general music and piano with the local organist, Johann Gottfried Kuntsch, and for a time he also had cello and flute lessons with one of the municipal musicians, Carl Gottlieb Meissner.[7] Throughout his childhood and youth his love of music and literature ran in tandem, with poems and dramatic works produced alongside small-scale compositions, mainly piano pieces and songs.[8] He was not a musical child prodigy like Mozart or Mendelssohn,[4] but his talent as a pianist was evident from an early age: in 1850 the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung (Universal Musical Journal) printed a biographical sketch of Schumann which included an account from contemporary sources that even as a boy he possessed a special talent for portraying feelings and characteristic traits in melody:

From 1820 Schumann attended the Zwickau Lyceum, the local high school of about two hundred boys, where he remained till the age of eighteen, studying a traditional curriculum. In addition to his studies he read extensively: among his early enthusiasms were Schiller and Jean Paul.[10] According to the musical historian George Hall, Paul remained Schumann's favourite author and exercised a powerful influence on the composer's creativity with his sensibility and vein of fantasy.[8] Musically, Schumann got to know the works of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and of living composers Weber, with whom August Schumann tried unsuccessfully to arrange for Robert to study.[8] August was not particularly musical but he encouraged his son's interest in music, buying him a Streicher grand piano and organising expeditions to Leipzig for a performance of Die Zauberflöte and Carlsbad to hear the celebrated pianist Ignaz Moscheles.[11]

University[edit]

August Schumann died in 1826; his widow was less enthusiastic about a musical career for her son and persuaded him to study for the law as a profession. After his final examinations at the Lyceum in March 1828 he entered Leipzig University. Accounts differ about his diligence as a law student. According to his room-mate Emil Flechsig, he never set foot in a lecture hall,[2] but he himself recorded, "I am industrious and regular, and enjoy my jurisprudence ... and am only now beginning to appreciate its true worth".[12] Nonetheless reading and playing the piano occupied a good deal of his time, and he developed expensive tastes for champagne and cigars.[8] Musically, he discovered the works of Franz Schubert, whose death in November 1828 caused Schumann to cry all night.[8] The leading piano teacher in Leipzig was Friedrich Wieck, who recognised Schumann's talent and accepted him as a pupil.[13]

After a year in Leipzig Schumann convinced his mother that he should move to the University of Heidelberg which, unlike Leipzig, offered courses in Roman, ecclesiastical and international law (as well as reuniting Schumann with his close friend Eduard Röller who was a student there).[14] After matriculating at the university on 30 July 1829 he travelled in Switzerland and Italy from late August to late October. He was greatly taken with Rossini's operas and the bel canto of the soprano Giuditta Pasta; he wrote to Wieck, "one can have no notion of Italian music without hearing it under Italian skies".[2] Another influence on him was hearing the violin virtuoso Niccolò Paganini play in Frankfurt in April 1830.[15] In the words of one biographer, "The easy-going discipline at Heidelberg University helped the world to lose a bad lawyer and to gain a great musician".[16] Finally deciding in favour of music rather than the law as a career he wrote to his mother on 30 July 1830 telling her how he saw his future: "My entire life has been a twenty-year struggle between poetry and prose, or call it music and law".[17] He persuaded her to ask Wieck for an objective assessment of his musical potential. Wieck's verdict was that with the necessary hard work Schumann could become a leading pianist within three years. A six-month trial period was agreed.[18]

1830s[edit]

Later in 1830 Schumann published his Op. 1, a set of piano variations on a theme based on the name of its supposed dedicatee, Countess Pauline von Abegg (who was almost certainly a figment of Schumann's imagination).[19] The notes A-B-E-G-G, played in waltz tempo, make up the theme on which the variations are based.[20] The use of a musical cipher became a recurrent characteristic of Schumann's later music.[8] In 1831 he began lessons in harmony and counterpoint with Heinrich Dorn, musical director of the Saxon court theatre,[21] and in 1832 he published his Op. 2, Papillons (Butterflies) for piano, a programmatic piece depicting twin brothers – one a poetic dreamer, the other a worldly realist – both in love with the same woman at a masked ball.[22] Schumann had by now come to regard himself as having two distinct sides to his personality and art: he dubbed his introspective, pensive self "Eusebius" and the impetuous and dynamic alter ego "Florestan".[23]

Schumann's pianistic ambitions were ended by a growing stiffness in the middle finger of his right hand. The early symptoms had come while he was still a student at Heidelberg, and the cause is uncertain.[24][n 2] He tried all the treatments then in vogue including allopathy, homeopathy, and electric therapy, but without success.[25] The condition had the advantage of exempting him from compulsory military service – he could not fire a rifle –[25] but by 1832 Schumann recognised that a career as a virtuoso pianist was impossible and shifted his main focus to composition. He completed further sets of small piano pieces and the first movement of a symphony (too thinly orchestrated according to Wieck).[2] An additional activity was journalism. From March 1834, along with Wieck and others, he was on the editorial board of a new music magazine, Neue Leipziger Zeitschrift für Musik (New Leipzig Music Magazine), which was reconstituted under his sole editorship in January 1835 as the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik.[2] Hall writes that it took "a thoughtful and progressive line on the new music of the day".[26] Among the contributors were friends and colleagues of Schumann, writing under pen names: he included them in his Davidsbündler (League of David) – a band of fighters for musical truth who warred with the Philistines – a product of the composer's imagination in which, blurring the boundaries of imagination and reality, he included his musical friends.[26]

During 1835 Schumann met three musicians whom he regarded with particular respect: Mendelssohn, Moscheles and Chopin.[27] Early in that year he completed two substantial compositions: Carnaval, Op.9 and the Symphonic Studies, Op.13. These works grew out of his romantic relationship with Ernestine von Fricken, a fellow pupil of Wieck. The musical themes of Carnaval derive from the name of her home town, Asch. The Symphonic Studies are based on a melody said to be by Ernestine's father, Baron von Fricken, an amateur flautist.[2] Schumann and Ernestine became secretly engaged, but in the view of the musical scholar Joan Chissell, during 1835 Schumann gradually realised that Ernestine's personality was not as interesting as he first thought, and this, together with his discovery that she was an illegitimate, impecunious, adopted daughter of Fricken, brought the affair to a gradual end.[28]

Schumann felt a growing attraction to Wieck's daughter, the sixteen-year-old Clara. She was her father's star pupil, a piano virtuoso with a growing reputation and emotionally mature beyond her years.[29] According to Chissell, her concerto debut at the Leipzig Gewandhaus on 9 November 1835, with Felix Mendelssohn conducting, "set the seal on all her earlier successes, and there was now no doubting that a great future lay before her as a pianist".[29] Schumann had watched her career approvingly since she was nine, but only now fell in love with her. His feelings were reciprocated: they declared their love to each other in January 1836.[30] Schumann expected that Wieck would welcome the proposed marriage, but he was mistaken: Wieck refused his consent, fearing that Schumann would be unable to provide for his daughter, that she would have to abandon her career, and that she would be legally required to relinquish her inheritance to her husband.[31] It took a series of acrimonious legal actions over the next four years for Schumann to obtain a court ruling that he and Clara were free to marry without her father's consent.[2]

Professionally the later years of the 1830s were marked by an abortive attempt by Schumann to establish himself in Vienna, and the beginning of an important friendship with Mendelssohn, who was by then based in Leipzig, conducting the Gewandhaus Orchestra and also by an increasing output of piano works including Kreisleriana (1837) Kinderszenen (Scenes from Childhood, 1838) and Faschingsschwank aus Wien (Carnival Prank from Vienna, 1839).[26] In 1838 Schumann visited Schubert's brother Ferdinand and discovered several manuscripts including that of the Great C major Symphony.[32] Ferdinand allowed him to take a copy away and Schumann arranged for the work's world premiere, conducted by Mendelssohn in Leipzig on 21 March 1839.[33] In the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik Schumann wrote enthusiastically about the work and described its "himmlische Länge" – its "heavenly length" – a phrase that has become common currency in later analyses of the symphony.[34]

1840s[edit]

Schumann and Clara finally married on 12 September 1840, the day before her twenty-first birthday.[35] Hall writes that marriage gave Schumann "the emotional and domestic stability on which his subsequent achievements were founded".[26] Clara made some sacrifices in marrying Schumann: as a pianist of international reputation she was the better-known of the two but her career was continually interrupted by motherhood of their seven children. She inspired Schumann in his composing career, encouraging him to extend his range as a composer beyond solo piano works.[26]

During 1840 Schumann turned his attention to song, producing more than half his total output of Lieder, including the cycles Myrthen ("Myrtles", a wedding present for Clara), Frauenliebe und Leben ("Woman's Love and Life"), Dichterliebe ("Poet's Love"), and settings of words by Joseph von Eichendorff and Heinrich Heine and others.[26]

In 1841 Schumann focused on orchestral music. On 31 March his First Symphony, The Spring, was premiered by Mendelssohn at a concert in the Gewandhaus at which Clara played Chopin's Second Piano Concerto and some of Schumann's works for solo piano.[36] Then came the Overture, Scherzo and Finale, the Phantasie for piano and orchestra (which later became the first movement of the Piano Concerto) and a new symphony (eventually published as the Fourth, in D minor). Clara gave birth to a daughter in September, the first of the Schumanns' seven children to survive.[26]

The following year Schumann turned his attention to chamber music. He studied works by Haydn and Mozart, despite an ambiguous attitude to the former: "Today it is impossible to learn anything new from him. He is like a familiar friend of the house whom all greet with pleasure and with esteem, but who has ceased to arouse any particular interest".[37] He was stronger in his praise of Mozart: "Serenity, repose, grace, the characteristics of the antique works of art, are also those of Mozart's school. The Greeks gave to 'The Thunderer' a radiant expression, and radiantly does Mozart launch his lightnings".[38] After his studies Schumann produced three string quartets, a Piano Quintet, a Piano Quartet, and a set of Phantasiestücke (Fantasy Pieces) for piano trio.[26]

1843 began with a setback to Schumann's career: he had a severe and debilitating mental crisis. This was not the first such attack, although it was the worst so far. Hall writes that he had been subject to similar attacks at intervals over a long period, and speculates that the condition may have been congenital, affecting Schumann's father and younger sister.[26] Later in the year, Schumann, having recovered, completed a successful oratorio, Das Paradies und die Peri (Paradise and the Peri), based on an oriental poem by Thomas Moore. It was premiered at the Gewandhaus on 4 December and repeat performances followed at Dresden on 23 December, Berlin early the following year, and in London in June 1856, when Schumann's friend William Sterndale Bennett conducted a performance given by the Philharmonic Society before Queen Victoria and the Prince Consort.[39] Although neglected after Schumann's death it remained popular throughout his lifetime and brought his name to international attention.[26] During 1843 Mendelssohn invited him to teach piano and composition at the new Leipzig Conservatory,[40] and Wieck approached him with an offer of reconciliation.[25] Schumann gladly accepted both, although the resumed relationship with his father-in-law remained polite rather than close.[25]

In 1844 Clara embarked on a concert tour of Russia; Schumann joined her. It was an artistic and financial success, and they were both immensely impressed by Saint Petersburg and Moscow,[2][41] but the tour was arduous and by the end Schumann was in a poor state both physically and mentally.[2] After he and Clara returned to Leipzig in late May he sold the Neue Zeitschrift, and in December the family moved to Dresden. Schumann had been passed over for the conductorship of the Leipzig Gewandhaus in succession to Mendelssohn, and he thought that Dresden, with a thriving opera house, might be the place where he could, as he now wished, become an operatic composer. His health remained poor. His doctor in Dresden reported complaints "from insomnia, general weakness, auditory disturbances, tremors, and chills in the feet, to a whole range of phobias".[42]

From the beginning of 1845 Schumann's health began to improve; he and Clara studied counterpoint together and both produced contrapuntal works for the piano. He added a slow movement and finale to the 1841 Phantasie for piano and orchestra, to create his Piano Concerto, Op 54.[43] The following year he worked on what was to be published as his Second Symphony, Op. 61. Progress on the work was slow, interrupted by further bouts of ill health.[44] When the symphony was complete he began work on his opera, Genoveva, which was not completed until August 1848.[45]

Between 24 November 1846 and 4 February 1847 the Schumanns toured in Vienna, Berlin and other cities. The Viennese leg of the tour was not a success. The performance of Schumann's First Symphony and Piano Concerto at the Musikverein on 1 January 1847 attracted a sparse and unenthusiastic audience, but in Berlin the performance of Das Paradies und die Peri was well received, and the tour gave Schumann the chance to see numerous operatic productions. In the words of Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, "A regular if not always approving member of the audience at performances of works by Donizetti, Rossini, Meyerbeer, Halévy and Flotow, he registered his 'desire to write operas' in his travel diary".[2] The Schumanns suffered several blows during 1847, including the death of their first son, Emil, born the year before, and the deaths of their friends Felix and Fanny Mendelssohn.[32] A second son, Ludwig, and a third, Ferdinand, were born in 1848 and 1849.[32]

1850s[edit]

Genoveva, a four-act opera based on the medieval legend of Genevieve of Brabant, was premiered in Leipzig, conducted by the composer, in June 1850. There were two further performances immediately afterwards, but the piece was not the success Schumann had been hoping for. In a 2005 study of the composer, Eric Frederick Jensen attributes this to Schumann's operatic style: "not tuneful and simplistic enough for the majority, not 'progressive' enough for the Wagnerians".[46] Liszt, who was in the first-night audience, revived Genoveva at Weimar in 1855 – the only other production of the opera in Schumann's lifetime.[47] Since then, according to Kobbé's Opera Book, despite occasional revivals Genoveva has remained "far from even the edge of the repertory".[48]

With a large family to support, Schumann sought financial security and with the support of his wife he accepted a post as director of music at Düsseldorf in April 1850. Hall comments that in retrospect it can be seen that Schumann was fundamentally unsuited for the post: "His diffidence in social situations, allied to mental instability, ensured that initially warm relations with local musicians gradually deteriorated to the point where his removal became a necessity in 1853".[49] During 1850 Schumann composed two substantial late works – the Third (Rhenish) Symphony and the Cello Concerto.[50] He continued to compose prolifically, and reworked some of his earlier works, including the D minor symphony from 1841, published as his Fourth Symphony (1851) and the 1835 Symphonic Studies (1852).[50]

In 1853 the twenty-year-old Johannes Brahms called on Schumann with a letter of introduction from their mutual friend the violinist Joseph Joachim. When Brahms began playing one of his piano sonatas, Schumann excitedly rushed out of the room and came back leading his wife by the hand, saying "Now, my dear Clara, you will hear such music as you never heard before; and you, young man, play the work from the beginning".[51] Schumann was so impressed that he wrote an article – his last – for the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik titled "Neue Bahnen" (New Paths), extolling Brahms as a musician who was destined "to give expression to his times in ideal fashion".[52]

Hall writes that Brahms proved "a personal tower of strength to Clara during the difficult days ahead": in early 1854 Schumann's health deteriorated drastically. On 27 February he attempted suicide by throwing himself into the Rhine.[49] He was rescued by fishermen, and at his own request he was admitted to a private sanatorium at Endenich, near Bonn, on 4 March. He remained there for more than two years, gradually deteriorating, with intermittent intervals of lucidity during which he wrote and received letters and sometimes essayed some composition.[2] The director of the sanatorium held that direct contact between patients and relatives was likely to distress all concerned and reduce the chances of recovery. Friends, including Brahms and Joachim, were permitted to visit Schumann but Clara did not see her husband until nearly two and a half years into his confinement, and only two days before his death.[2] Schumann died at the sanatorium aged 46 on 29 July 1856, the cause of death being recorded as pneumonia.[53][n 3]

Works[edit]

Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians (2001) begins its entry on Schumann: "[G]reat German composer of surpassing imaginative power whose music expressed the deepest spirit of the Romantic era", and concludes: "As both man and musician, Schumann is recognized as the quintessential artist of the Romantic era in German music. He was a master of lyric expression and dramatic power, perhaps best revealed in his outstanding piano music and songs ..."[59][60]

Solo piano[edit]

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Praesent maximus egestas urna sed auctor. Mauris ipsum nisl, dignissim tristique nisi et, iaculis placerat nunc. Suspendisse ut dictum augue. Vestibulum fringilla, neque eu finibus elementum, dui neque iaculis leo, eget congue ligula ipsum a lorem. Donec id tincidunt nibh, sed semper odio. Cras imperdiet, ligula ac efficitur dignissim, risus elit mattis lorem, quis aliquet arcu justo ac leo. Curabitur posuere aliquam elit, vitae pellentesque ex commodo vel. Sed laoreet vehicula ultricies. Aenean nec fringilla sapien. Duis eu mi vitae arcu tincidunt rhoncus euismod vitae augue. Morbi faucibus lectus vel erat aliquet ultrices. In ut finibus orci.

Maecenas sed fermentum lacus. Morbi at viverra ante. Cras posuere faucibus nisi, non ultrices purus fringilla vel. Phasellus tortor magna, dapibus id gravida a, fringilla ut mauris. Aliquam laoreet purus sapien, at accumsan nulla mattis non. Maecenas volutpat nibh eros, at pulvinar arcu lobortis id. Integer quis vulputate dolor, ac condimentum ligula. Etiam id turpis lorem. Duis sollicitudin placerat lacus sed egestas. Cras quis eros a enim tristique facilisis. In mauris ipsum, finibus non nunc ut, congue blandit lacus. Donec sodales justo pellentesque tellus ultricies, et malesuada arcu tempor.

Curabitur rutrum eros a interdum efficitur. Pellentesque habitant morbi tristique senectus et netus et malesuada fames ac turpis egestas. Vestibulum at metus vitae turpis egestas faucibus. Fusce semper est vitae eros efficitur rutrum. Suspendisse interdum suscipit erat id cursus. Pellentesque sit amet nisi non augue viverra laoreet. Cras vitae mattis velit. Integer sit amet placerat massa. Aliquam laoreet purus sapien, at accumsan nulla mattis non. Maecenas volutpat nibh eros, at pulvinar arcu lobortis id. Integer quis vulputate dolor, ac condimentum ligula. Etiam id turpis lorem. Duis id tempus neque. Donec in molestie nisi. Donec interdum luctus erat et ullamcorper. Nullam eleifend mi scelerisque sodales mollis. Proin sit amet tortor a ex pretium imperdiet quis et ante. Duis mattis ex tortor, quis mattis lacus tristique a. Fusce rutrum eleifend elit eget consectetur.

Songs[edit]

Schumann wrote more than 200 songs for solo voice and piano.[61] They are known for the quality of the texts he set: Hall comments that the composer's youthful appreciation of literature was constantly renewed in adult life.[61] Among the best-known of the songs are those in four cycles composed in 1840 – a year Schumann called his Liederjahr (year of song).[62] These are Dichterliebe (Poet's Love) comprising sixteen songs with words by Heinrich Heine; Frauenliebe und Leben (Woman's Love and Life), eight songs setting poems by Adelbert von Chamisso; and two sets simply titled Liederkreis – German for "Song Cycle" – the Op. 24 set, consisting of nine Heine settings and the Op. 39 set of twelve settings of poems by Joseph von Eichendorff.[2] Also from 1840 is the set Schumann wrote as a wedding present to Clara, Myrthen (Myrtles – traditionally part of a bride's wedding bouquet),[63] which the composer called a song cycle, although with twenty-six songs with lyrics from ten different writers this set is a less unified cycle than the others. In a study of Schumann's songs Eric Sams suggests that even here there is a unifying theme, namely the composer himself.[64]

Although during the twentieth century it became common practice to perform these cycles as a whole, in Schumann's time and beyond it was usual to extract individual songs for performance in recitals. The first documented public performance of a complete Schumann song cycle was not until 1861, five years after the composer's death; the baritone Julius Stockhausen sang Dichterliebe with Brahms at the piano.[65] Stockhausen also gave the first complete performances of Frauenliebe und Leben and the Op. 24 Liederkreis.[65]

After his Liederjahr Schumann returned in earnest to writing songs after a break of several years. Hall described the the variety of the songs as immense, and comments that some of the later songs are entirely different in mood from the composer's earlier Romantic settings. Schumann's literary sensibilities led him to create in his songs an equal partnership between words and music unprecedented in the German Lied.[61] His affinity with the piano is heard in his accompaniments to his songs, notably in their preludes and postludes, the latter often summing up what has been heard in the song.[61]

Orchestral[edit]

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Praesent maximus egestas urna sed auctor. Mauris ipsum nisl, dignissim tristique nisi et, iaculis placerat nunc. Suspendisse ut dictum augue. Vestibulum fringilla, neque eu finibus elementum, dui neque iaculis leo, eget congue ligula ipsum a lorem. Donec id tincidunt nibh, sed semper odio. Cras imperdiet, ligula ac efficitur dignissim, risus elit mattis lorem, quis aliquet arcu justo ac leo. Curabitur posuere aliquam elit, vitae pellentesque ex commodo vel. Sed laoreet vehicula ultricies. Aenean nec fringilla sapien. Duis eu mi vitae arcu tincidunt rhoncus euismod vitae augue. Morbi faucibus lectus vel erat aliquet ultrices. In ut finibus orci.

Maecenas sed fermentum lacus. Morbi at viverra ante. Cras posuere faucibus nisi, non ultrices purus fringilla vel. Phasellus tortor magna, dapibus id gravida a, fringilla ut mauris. Aliquam laoreet purus sapien, at accumsan nulla mattis non. Maecenas volutpat nibh eros, at pulvinar arcu lobortis id. Integer quis vulputate dolor, ac condimentum ligula. Etiam id turpis lorem. Duis sollicitudin placerat lacus sed egestas. Cras quis eros a enim tristique facilisis. In mauris ipsum, finibus non nunc ut, congue blandit lacus. Donec sodales justo pellentesque tellus ultricies, et malesuada arcu tempor.

Curabitur rutrum eros a interdum efficitur. Pellentesque habitant morbi tristique senectus et netus et malesuada fames ac turpis egestas. Vestibulum at metus vitae turpis egestas faucibus. Fusce semper est vitae eros efficitur rutrum. Suspendisse interdum suscipit erat id cursus. Pellentesque sit amet nisi non augue viverra laoreet. Cras vitae mattis velit. Integer sit amet placerat massa. Aliquam laoreet purus sapien, at accumsan nulla mattis non. Maecenas volutpat nibh eros, at pulvinar arcu lobortis id. Integer quis vulputate dolor, ac condimentum ligula. Etiam id turpis lorem. Duis id tempus neque. Donec in molestie nisi. Donec interdum luctus erat et ullamcorper. Nullam eleifend mi scelerisque sodales mollis. Proin sit amet tortor a ex pretium imperdiet quis et ante. Duis mattis ex tortor, quis mattis lacus tristique a. Fusce rutrum eleifend elit eget consectetur.

Chamber[edit]

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Praesent maximus egestas urna sed auctor. Mauris ipsum nisl, dignissim tristique nisi et, iaculis placerat nunc. Suspendisse ut dictum augue. Vestibulum fringilla, neque eu finibus elementum, dui neque iaculis leo, eget congue ligula ipsum a lorem. Donec id tincidunt nibh, sed semper odio. Cras imperdiet, ligula ac efficitur dignissim, risus elit mattis lorem, quis aliquet arcu justo ac leo. Curabitur posuere aliquam elit, vitae pellentesque ex commodo vel. Sed laoreet vehicula ultricies. Aenean nec fringilla sapien. Duis eu mi vitae arcu tincidunt rhoncus euismod vitae augue. Morbi faucibus lectus vel erat aliquet ultrices. In ut finibus orci.

Maecenas sed fermentum lacus. Morbi at viverra ante. Cras posuere faucibus nisi, non ultrices purus fringilla vel. Phasellus tortor magna, dapibus id gravida a, fringilla ut mauris. Aliquam laoreet purus sapien, at accumsan nulla mattis non. Maecenas volutpat nibh eros, at pulvinar arcu lobortis id. Integer quis vulputate dolor, ac condimentum ligula. Etiam id turpis lorem. Duis sollicitudin placerat lacus sed egestas. Cras quis eros a enim tristique facilisis. In mauris ipsum, finibus non nunc ut, congue blandit lacus. Donec sodales justo pellentesque tellus ultricies, et malesuada arcu tempor.

Curabitur rutrum eros a interdum efficitur. Pellentesque habitant morbi tristique senectus et netus et malesuada fames ac turpis egestas. Vestibulum at metus vitae turpis egestas faucibus. Fusce semper est vitae eros efficitur rutrum. Suspendisse interdum suscipit erat id cursus. Pellentesque sit amet nisi non augue viverra laoreet. Cras vitae mattis velit. Integer sit amet placerat massa. Aliquam laoreet purus sapien, at accumsan nulla mattis non. Maecenas volutpat nibh eros, at pulvinar arcu lobortis id. Integer quis vulputate dolor, ac condimentum ligula. Etiam id turpis lorem. Duis id tempus neque. Donec in molestie nisi. Donec interdum luctus erat et ullamcorper. Nullam eleifend mi scelerisque sodales mollis. Proin sit amet tortor a ex pretium imperdiet quis et ante. Duis mattis ex tortor, quis mattis lacus tristique a. Fusce rutrum eleifend elit eget consectetur.

Notes, references and sources[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b Many sources from the 19th century onwards state that Schumann had the middle name Alexander,[1] but according to the 2001 edition of Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians and a 2005 biography by Eric Frederick Jensen there is no evidence that he had a middle name and it is possibly a misreading of his teenage pseudonym "Skülander". His birth and death certificates and all other existing official documents give "Robert Schumann" as his only names.[2][3]

- ^ Wieck believed the damage was done by Schumann's use of a chiroplast – a finger-stretching device then favoured by pianists; the biographer Eric Sams has theorised that the affliction was caused by mercury poisoning as a side effect of treatment for syphilis, a hypothesis subsequently discounted by neurologists.[24]

- ^ As with the hand ailment earlier in his life, Schumann's decline and death have been the subject of much conjecture. In Grove, John Daverio and Eric Sams suggest tertiary syphilis, long dormant, as the cause, and the official certification as death from pneumonia as intended to spare Clara's feelings.[2] This view is given varying degrees of credence by Joan Chissell, Alan Walker and Tim Dowley,[54][55][56] and is not endorsed by Eric Frederick Jensen and Martin Geck, who regard the evidence for syphilis as unconvincing.[57] [58]

References[edit]

- ^ Liliencron, p. 44; Spitta, p. 384; Slonimsky and Kuhn, p. 3234; and Wolff p. 1702

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Daverio, John and Eric Sams. "Schumann, Robert", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2001 (subscription required)

- ^ Jensen, p. 2

- ^ a b c Perrey, Schumann's lives, p. 6

- ^ Dowley, p. 7

- ^ Chissell, p. 3

- ^ Geck, p. 8

- ^ a b c d e f Hall, p. 1125

- ^ Wasielewski, p. 11

- ^ Geck, p. 49

- ^ Chissell, p. 4

- ^ Chissell, p. 16

- ^ Jensen, p. 22

- ^ Dowley, p. 27

- ^ Taylor, p. 58

- ^ "Robert Schumann", The Musical Times, Vol. 51, No. 809 (1 July 1910), pp. 426

- ^ Jensen, p. 34

- ^ Jensen, p. 37

- ^ Geck, p. 62; and Jensen, p. 97

- ^ Taylor, p. 72

- ^ Jensen, p. 64

- ^ Taylor, p. 74

- ^ Dowley, p. 46

- ^ a b Ostwald, pp. 23 and 25

- ^ a b c d Slonimsky and Kuhn, pp. 3234–3235

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hall, p. 1126

- ^ Perrey, Chronology, p. xiv

- ^ Chissell, p. 36

- ^ a b Chissell, p. 37

- ^ Chissell, p. 38

- ^ Geck, p. 98

- ^ a b c Perrey, Chronology, p. xv

- ^ Marston, p. 51

- ^ Maintz, p. 100; and Marston, p. 51

- ^ Dowley, p. 66

- ^ Dowley, p. 74

- ^ Schumann, p. 94

- ^ Schumann, pp. 94–95

- ^ Browne Conor. "Robert Schumann's Das Paradies und die Peri and its early Performances", Thomas Moore in Europe, Queen’s University Belfast, 31 May 2017; and "Philharmonic Concerts", The Times, 24 June 1856, p. 12

- ^ Perrey, Chronology, p. xvi

- ^ Daverio, p. 286

- ^ Daverio, p. 299

- ^ Daverio, p. 305

- ^ Daverio, p. 298

- ^ Walker, p. 93

- ^ Jensen, p. 235

- ^ Jensen, pp. 316–317

- ^ Harewood, pp. 718–719

- ^ a b Hall, p. 1127

- ^ a b Perrey, Chronology, p. xvii

- ^ Walker, p. 110

- ^ Schumann, pp. 252–254

- ^ Daverio, p. 568

- ^ Chissell, p. 77

- ^ Walker, p. 117

- ^ Dowley, p. 117

- ^ Jensen, p. 329

- ^ Geck, p. 251

- ^ Slonimsky and Kuhn, p. 3234

- ^ Slonimsky and Kuhn, p. 3236

- ^ a b c d Hall, pp. 1126–1127

- ^ Ferris, p. 251

- ^ Finson, p. 21

- ^ Sams, p. 50

- ^ a b Reich p. 222

Sources[edit]

- Chissell, Joan (1989). Schumann (Fifth ed.). London: Dent. ISBN 978-0-46-012588-8.

- Daverio, John (1997). Robert Schumann: Herald of a "New Poetic Age". New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509180-9.

- Dowley, Tim (1982). Schumann: His Life and Times. Neptune City: Paganiniana. ISBN 978-0-87-666634-0.

- Finson, Jon W. (2007). Robert Schumann. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674026292.

- Geck, Martin (2013) [2010]. Robert Schumann: The Life and Work of a Romantic Composer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-22-628469-9.

- Hall, George (2002). "Robert Schumann". In Alison Latham (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Music. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866212-9.

- Harewood, Earl of (2000) [1922]. "Robert Schumann". In Earl of Harewood; Anthony Peattie (eds.). The New Kobbé's Opera Book (eleventh ed.). London: Ebury Press. ISBN 978-0-09-181410-6.

- Jensen, Eric Frederick (2005). Schumann. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-983068-8.

- Liliencron, Rochus von (1875). Allgemeine deutsche Biographie (in German). Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot. OCLC 311366924.

- Maintz, Marie Luise (1995). Franz Schubert in der Rezeption Robert Schumanns: Studien zur Ästhetik und Instrumentalmusik (in German). Kassel and New York: Bärenreiter. ISBN 978-3-76-181244-0.

- Marston, Phlip (2007). "Schumann's heroes". In Beate Perrey (ed.). Cambridge Companion to Schumann. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-00154-0.

- Ostwald, Peter (Summer 1980). "Florestan, Eusebius, Clara, and Schumann's Right Hand". 19th-Century Music: 17–31. (subscription required)

- Perrey, Beate (2007). "Chronology". In Beate Perrey (ed.). Cambridge Companion to Schumann. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-00154-0.

- Perrey, Beate (2007). "Schumann's lives, and afterlives". In Beate Perrey (ed.). Cambridge Companion to Schumann. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-00154-0.

- Reich, Nancy B. (1988). Clara Schumann: The Artist and the Woman. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-80-149388-1.

- Sams, Eric (1969). The Songs of Robert Schumann. London: Methuen. ISBN 978-0-41-610390-8.

- Schumann, Robert (1946). Konrad Wolff (ed.). On Music and Musicians. New York: Norton. OCLC 583002.

- Slonimsky, Nicolas; Laura Kuhn, eds. (2001). Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Vol. 5. New York: Schirmer. ISBN 978-0-02-865530-7.

- Spitta, Philipp (1879). "Schumann, Robert". In George Grove (ed.). A Dictionary of Music and Musicians. London and New York: Macmillan. OCLC 1043255406.

- Taylor, Ronald (1985) [1982]. Robert Schumann: His Life and Work. London: Panther. ISBN 978-0-58-605883-1.

- Walker, Alan (1976). Schumann. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-57-110269-3.

- Wasielewski, Wilhelm Joseph von (1869). Robert Schumann: eine Biographie (in German). Dresden: Kuntze. OCLC 492828443.

- Wolff, Anita, ed. (2006). Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. Chicago: Britannica. ISBN 978-1-59339-492-9.