User:Virginiawhite09/sandbox

| Part of a series on |

| Feminism |

|---|

|

|

|

Feminist economics refers to an intellectual stream in economic thought which applies feminist lenses to economics in order to challenge the androcentric biases inherent within it and produce an economics that is more gender inclusive.[1] Feminist economists claim that contrary to common conceptions "the discipline of economics is a creation of groups of people" and is "malleable over time." Consequently, they claim, the contemporary construction of economics focuses on "culturally 'masculine' topics" including "autonomy, abstraction and logic" to the exclusion of "feminine" topics "such as women and family behavior as well as...connection, concreteness and emotion." [2] Feminist economics critically examines economic epistemology and methodology, emphasizes areas of traditional economic inquiry that have a particular relevance to women (for example, care work), and ultimately seeks to reform the field of economics itself.

More specifically, feminist economists challenge the neoclassical economic assumptions 1) that interpersonal utility comparisons are impossible 2) that tastes are exogenous and unchanging 3) that actors are selfish and 4) that household heads act altruistically[3], among others. Additionally, feminist economists are concerned with examining phenomena poorly represented by existing models and, subsequently, using different forms of data collection and interpretation to produce more gender-aware theories.

Origins and history[edit]

Early on, feminist ethicists, economists, political scientists and systems scientists argued that women's traditional work (e.g. child-raising, caring for sick elders) and occupations (e.g. nursing, teaching) are systematically undervalued with respect to that of men. For example, Jane Jacobs' thesis of the "Guardian Ethic" and its contrast to the "Trader Ethic" sought to explain what feminist economics claim is the systematic undervalueing of guardianship activity, including the child-protecting, nurturing, and healing tasks that were traditionally assigned to women. Measures such as employment equity were implemented in developed nations in the 1970s to 1990s, but these were not entirely successful in removing wage gaps even in nations with strong equity traditions.

While attention to women’s economic role and economic differences by gender started in the 1960s and there were feminist critiques of received economic theories in the 1970s and 1980s including those presented at the Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession (CSWEP) in 1972,[4] feminist economics took off in earnest with the founding of the International Association for Feminist Economics (IAFFE) and the journal Feminist Economics in 1994.[5]

As in other disciplines, the initial emphasis of feminist economists was to critique the established theory, methodology, and policy approaches. The critique began in microeconomics of the household and labor markets and spread to macroeconomics and international trade, leaving no field in economics untouched.[6] Feminist economists pushed for and produced gender aware theory and analysis, broadened the focus on economics and sought pluralism of methodology and research methods.

Critiques of neoclassical economics[edit]

Although there is no definitive list of the principles of feminist economics [7] feminist economists offer a variety of critiques of neoclassical economics.

Economics as a normative science[edit]

Central to many feminist economic critiques is the recognition of value judgments in economic analysis. In other words, feminist economists suggest that "the issues that economists choose to study, the kinds of questions they ask, and the type of analysis undertaken all are a product of a belief system which is influenced by numerous factors, some of them ideological in character." This idea is contrary to the typical conception of economics as a positive science. [8] For example, Diana Strassmann comments, "All economic statistics are based on an underlying story forming the basis of the definition. In this way, narrative constructions necessarily underlie all definitions of variables and statistics. Therefore, economic research cannot escape being inherently qualitative, regardless of how it is labeled." [9] As a result, feminist economists call for a discipline wide recognition of the value-laden decisions in the discipline.

Decision making re-conceptualized[edit]

Feminist economists highlight that, contrary to neoclassical assumptions, individual economic decisions are deeply affected by social factors. Additionally, feminist economics emphasize that traditional economics is overly focused on individual decision making to the exclusion of other choice-making models.

Critiques of free trade[edit]

A central principle of mainstream economics is "trade can make everyone better off" through efficiency gains from specialization and enhanced global efficiency [10]. Many feminist economics may, however, wish to modify this claim. For example, they may highlight that in Africa, specialization in the cultivation of a single cash crop for export in many countries made these countries extremely vulnerable to price fluctuations, weather patterns, and pests. [11] Feminist economics may also consider the specific gendered effects of trade-deicisons. For example, "in countries such as Kenya, men generally controlled the earnings from cash crops while women were still expected to provide food and clothing for the household, their traditional role in the African family, along with labor to produce cash crops. Thus women suffered significantly from the transition away from subsistence food production towards specialization and trade."[12]

Non-market activity focus[edit]

Feminist economics call attention to the importance of non-market activities, such as childcare and domestic work, to the development of the economy.

Power relations in economic models[edit]

Feminist economics often assert that power relations exist within the economy, and therefore, must be assessed in economic models in ways that they previously have been overlooked. For example, "neoclassical texts, the sale of labor is viewed as a mutually beneficial exchange that benefits both parties. No mention is made of the power inequities in the exchange which tend to give the employer power over the employee. Nor is any mention made of the particular difficulties that confront women in the workplace. Understanding power and patriarchy helps us to analyze how male-dominated economic institutions actually function and why women are often at a disadvantage in the workplace." [13]

Gender and race[edit]

Feminist economics argue that gender and race must be considered in economic analysis. Matthaei [14] describes the importance of gender and racial-ethnic factors to the field of economics in the following passage: "Not only did gender and racial-ethnic differences and inequality precede capitalism, they have been built into it in key ways. In other words, every aspect of our capitalist economy is gendered and racialized; a theory and practice that ignores this is inherently flawed."

More specifically, this analysis includes considerations of the sexual division of labor. Feminist research in these areas directly contradicts the neoclassical description of labor markets in which occupations are chosen freely by individuals acting alone. Thus economic relationships and actions are directly affected by gender roles, and a gendered perspective illuminates this aspect of the economy that would otherwise be ignored. [15]

Reformation of economic actors[edit]

In neoclassical economics "people are viewed as rational, and rational people engage in marginal analysis. Feminist economists have demonstrated that people are more than just rational entities who act individually through marginal analysis. Instead, feminist economists attempt to construct a more holistic vision of an economic actor, which includes group interactions and actions motivated by factors other than greed." [16] In addition, in contrast to "rational actor" models of economics, feminists have drawn attention to the problems of those who lack agency, such as children, the sick, and the frail elderly, and the way in which responsibilities for their care can serve to compromise the agency of their caregivers.

Moreover, feminist economists critique the central focus in neoclassical economics on monetary rewards "As Nancy Folbre (1998, 161) notes, "legal rules and cultural norms can affect market outcomes in ways distinctly disadvantageous to women." Feminist economics includes the study of norms because of their importance to economic issues. Folbre (1998, 167) goes on to say that "increased reliance on forms of labor motivated entirely by pecuniary concerns poses some genuine risks to dependents, like children, the sick, and the elderly, who cannot monitor or control workers who provide them with services." Thus the view that material incentives will provide the goods we want and need (consumer sovereignty) does not capture the realities of economic life for many people."

Selfishness is not universal[edit]

Feminist economists argue that mainstream economics overemphasizes the role of individualism, competition and selfishness. Instead, feminist economists like Nancy Folbre state that cooperation also plays a role in the economy.

Economic analysis must be interdisciplinary and expanded[edit]

Often economists is conceptualized as "the study of how society manages its scarce resources."[17] Feminist economists, however, argue that this conception of economics must be expanded.

Major areas of inquiry[edit]

Economic epistemology[edit]

Feminist economists call attention to the ways that mainstream economics privilege male-identified, western, and heterosexual interpretations of economic life. More broadly, they incorporate feminist frameworks to show how communities of knowledge inherently signal their expectations regarding appropriate participants in their communities, to the exclusion of non-in-group members. Such criticisms extend to the theories, methodologies and central ares of research of economics.

Economic history[edit]

Feminist economics highlight that mainstream economics has been disproportionately constructed by European-descended, heterosexual, middle and upper-middle class men and that this has led to a conception of economics that overlooks the lived experiences of the diversity of the world's people, especially women, children and those in non-traditional family units.

Well-being[edit]

Many feminist economics argue for a reconception of economics focused less on economic mechanisms and more on the well-being of all people. Many feminist economists argue that economic success cannot only be measured in terms of goods or gross domestic product, but must also be measured by human well-being. Further, feminist economics claim that aggregate income is not sufficient to evaluate economic well-being, but that instead individual entitlements and needs must be taken into account.

For example, Amartya Sen, Sakiko Fukuda-Parr, and other feminist economists contributed to the development of alternatives to GDP, such as the Human Development Index.

Human Capabilities Approach[edit]

Feminist economist Amartya Sen was instrumental in creating the human capabilities approach, an alternative means to assess economic success rooted in the ideas of welfare economics. [18] [19] Unlike traditional economic measures of success, focused on GDP, utility, income, assets or other monetary measures, the capabilities approach focuses on what individuals are able to do. Following Sen, other feminist economists including Martha Nussbaum, expanded on the model. And, in recent years, the capabilities approach has influenced influential models including the UN's Human Development Index (HDI)

Household bargaining[edit]

Central to feminist economic approaches is a retheorizing of "the family" and "the household." In classical economics these units are typically described as amicable and homogeneous. Feminist economists modify these assumptions to account for exploitative sexual and gender relations, single-parent families, same-sex relationships, familial relations with children and the consequences of reproduction. Specifically, feminist economists move beyond unitary household models and game theory to call attention to the diversity of household experiences.

Mainstream economists usually assume the family is a single, altruistic unit and that the inputs (i.e. money) are distributed equally. Bina Agarwal and other feminist economists have critiqued the mainstream model and contributed to a better understanding of intrahousehold bargaining power. Agarwal argues that a lack of power and outside options for women hinders womens' abilities to negotiate within the family unit. Amartya Sen highlights how social norms that devalue women's unpaid work in the household often disadvantages women in intra-household bargaining. Crucially, these feminist economists argue that these claims have important economic outcomes that must be recognized within the economic framework.

Paid and unpaid work in the care economy[edit]

Feminist economists acknowledge care work as central to economic development and human well-being. Feminist economists examine both paid and unpaid care work. Feminist economists argue that traditional analysis of economic systems often fails to take into account the value of the unpaid work being performed by men and women in a domestic setting. Feminist economists have argued that unpaid domestic work is just as valuable as paid work and that measures of economic success should take unpaid work into account when evaluating economic systems. In addition, feminist economists have also drawn attention to issues of power and inequality within families and households. The work of the Equality Studies Department at University College Dublin, and, in particular of Urningin Sara Cantillon has focused on the internal inequalities of domestic economic arrangements which occur even within affluent households.

Additionally, while much care work is performed in the home, care work may also take the form of paid work. As such, feminist economics examine the implications of paid care work, from the increasing involvement of women in the paid sphere, the potentials for exploitation in this arena, to the personal affects on the lives of care workers.

Systemic study of the ways women's work is measured or not measured at all, undertaken by Marilyn Waring (see If Women Counted) and others in the 1980s and 1990s, began to justify different means of determining value - some of which were influential in the theory of social capital and individual capital, which emerged in the late 1990s and, along with ecological economics, influenced modern human development theory. See also the entry on Gender and Social Capital.

Unpaid work[edit]

Defining Unpaid Work[edit]

Unpaid work can be separated into multiple categories: domestic work, care work, subsistence work, unpaid market labor and voluntary work. There are no clear consensuses on the definitions of each category; however, broadly, these types of work can be considered as contributing to the reproduction of society.

Domestic work is activities done in the maintenance of the home, and which are universally recognizable, such as doing the laundry. Care work is work done by someone who is looking “after a relative or friend who needs support because of age, physical or learning disability, or illness, including mental illness” [20]; this work also includes the raising of children. Another aspect of the definition of care work “calls attention to activities that involve close personal or emotional interaction” [21]. Also included in this category is “self-care,” in which leisure time and activities may be considered. Subsistence work is work done in order to meet base needs, such as collecting water, which do not have any market values assigned to them; although some of these activities “are categorized as productive activities according to the latest revision of the international System of National Accounts (SNA)…but are poorly measured by most surveys” [21]. Unpaid market work is understood as “the direct contributions of unpaid family members to market work that officially belongs to another member of the household” [22]. Voluntary work is usually understood as work done outside of the home, but for little to no remuneration.

Mainstream Methods of Measurement[edit]

Although each country measures it’s economic output, the most widespread method is the System of National Accounts (SNA), sponsored mainly by the United Nations (UN), but implemented by various other organizations, such as the European Commission, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and the World Bank. The SNA recognizes that unpaid work is an area of interest, however, “unpaid household services are excluded from [it’s] production boundary” [23]. Feminist economists have criticized this system for this exclusion, as it is argued that by leaving out unpaid work, basic and necessarily labor is uncounted.

Even accounting measures intended to recognize gender disparities are criticized for ignoring this type of work. Two such examples are the Gender-related Development Index (GDI) and the Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM). It is argued that neither index indicates much about unpaid work [24]. Despite these efforts to better measure gender inequalities, there is a call for a more comprehensive index is needed, which includes participation in unpaid work.

In more recent years, there has been increasing attention to this issue, such as the recognition of the issue within the SNA reports, and a “UN commitment to ‘measuring and valuing unpaid work’ with specific attention to women's family care giving – reproduction and household activities. This aim was reaffirmed at the 1995 UN Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing” [25].

Alternative Methods of Measurement[edit]

The method most widely used is gathering information on time use, which has “been implemented by at least 20 developing countries and more are underway” [21]. Information is collected on how much time men and women spend on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis on certain activities that fall under the categories of unpaid work. Techniques to gather this data include surveys [25], in-depth interviews [25], diaries [26], and participant observation[25]. Proponents of time use diaries believe that this method “generate[s] more detailed information and tend[s] to capture greater variation than predetermined questions” [25]. However, others argue that participant observation, “where the researcher spends lengthy periods of time in households helping out and observing the labor process” [25], generates more accurate information, as the researcher can ascertain whether or not those studied are accurately reporting what activities they perform.

Problems[edit]

The first problem regarding the measurement of unpaid work is the issue of collecting accurate information. This is always a concern in research studies, however, because of the magnitude of this problem in this topic, it is of special concern. “Time-use surveys may reveal relatively little time devoted to unpaid direct care activities [because] the demands of subsistence production in those countries are great” [21], and may not take into account multitasking – for example, a mother may collect wood fuel while a child is in the same location, so the child is in her care (an indirect form of care work). It is usually argued that indirect care should be included, and it is in may time use studies, however, it may not be and as a result studies may undercount the amount of certain types of unpaid work. Surveys have also been criticized for lacking “depth and complexity” [25] as questions cannot be specifically tailored. Participant observation has been criticized for being “so time- consuming that it can only focus on small numbers of households” [25], and so limited information is gathered.

A problem all types of data gathering run into is that the people who participate in these studies may not report accurately, for whatever reasons, perhaps the “people doing domestic labor have [had] no reason to pay close attention to the amount of time tasks take and they [may] often underestimate time spent in familiar activities” [25]. Using time as a measure has also been criticized as it may show “the slowest and most inefficient workers…as carrying the greatest workload” [25]. In addition, time use in assessing childcare is criticized as “easily obscur[ing] gender differences in workload. Men and women may both put in the same amount of time being responsible for children but as participant observation studies have shown, many men are more likely to ‘babysit’ their children while doing some- thing for themselves, such as watching TV. Their standards of care may be limited to ensuring the children are not hurt; dirty diapers may be ignored or deliberately left until the mother returns” [25]. Another paradoxical aspect of this problem is that those most burdened may not be able to participate in the studies – “it is usually those women with the heaviest work loads who choose not to participate in these studies” [25]. In general, a criticism to be made is the use of time as a general measure and by its use “some of the most demanding aspects of unpaid work [are unexplored] and the premise that time is an appropriate tool for measuring women's unpaid work goes unchallenged” [25].

A second problem noted concerning this topic is the unease of comparability across societies. “Comparisons across countries are currently hampered by differences in activity classification and nomenclature” [21]. In-depth surveys may be the only way to get the depth of information desired, but make it difficult to make cross-cultural comparisons [25]. A more specific aspect of this problem is the lack of adequate universal terminology in discussing unpaid work. “Despite increasing recognition that domestic labor is work, existing vocabularies do not easily convey the new appreciations. People still tend to talk about work and home as if they were separate spheres. ‘Working mothers’ are usually assumed to be in the paid labor force, despite feminist assertions that "every mother is a working mother." There are no readily accepted terms to express different work activities or job titles. Housewife, home manager, homemaker are all problematic and none of them conveys the sense of a women who juggles both domestic labor and paid employment” [25].

A third problem is the complexity of domestic labor and the issues of separating unpaid work categories. Time use studies are now taking into account multitasking issues, where activities are separated into primary and secondary activities, however, not all studies do this and even those that do may not take into account “the fact that frequently several tasks are done simultaneously, that tasks overlap, and that the boundaries between work and relationships are often unclear. How does a woman determine her primary activity when she is preparing dinner while putting the laundry away, making coffee for her spouse, having coffee and chatting with him, and attending to the children”[25]. Some activities may not even be considered work, such as playing with a child (this has been categorized as developmental care work), by the caregiver, and so may not be included in the responses to a study [25]. As mentioned before, supervision (indirect care work) may not be “construe[d] as an activity at all” [21], which “suggests that activity-based surveys should be supplemented by more stylized questions regarding care responsibilities”[21] as these activities may be undercounted [21]. In the past, time use studies tended to measure only primary activities, and “respondents doing two or more things at once were asked to indicate which was the more important” [25], although this is changing in more recent years.

Valuation[edit]

Feminist economists argue for three main ways of valuating unpaid work: opportunity cost method, replacement cost method, and input-output cost method. Opportunity cost method “uses the wage a person would earn in the market” [26] to see how much value their labor-time has. This method extrapolates from the opportunity cost theory in mainstream economics.

The second method of valuation uses replacement costs. In simple terms, this is done by measuring the amount of money a third-party would make for doing the same work if it was part of the market. In other words, the value of a person cleaning the house in an hour is the same as the hourly wage for a maid. Within this method there are two approaches: the first is a generalist replacement cost method, which examines if “it would be possible, for example, to take the wage of a general domestic worker who could perform a variety of tasks including childcare” [26]. The second approach is the specialist replacement cost method, which aims to “distinguish between the different household tasks and choose replacements accordingly” [26].

The third method is input-output cost method. This looks at both the costs of inputs and includes any value added by the household. “For instance, the value of time devoted to cooking a meal can be determined by asking what it could cost to purchase a similar meal (or output) in the market, then subtracting the cost of the capital goods, utilities and raw materials devoted to that meal. This remainder represents the value of the other factors of production, primarily labor” [21]. These types of models try to value household output by determining monetary values for the inputs (in the dinner example: for the ingredients and production of the meal) and compare these with formal market equivalents [25].

Problems[edit]

These methods, too, have been criticized. At the basic level, one criticism is on how monetary levels are chosen. A question which need to be addressed is how unpaid work should be valued when more than one activity is being performed or more than one output produced? Another issue is differences in quality between market products and household products. Some feminist economists take issue with using the market system to determine values. Reasons for this objection include: it may lead to the conclusion that “the market provides perfect substitutes for non-market work” [21]; the wage produced in the market for services may not accurately reflect “the actual opportunity cost of time spent in household production” [26]; and the wages used in valuation methods come from industries where wages are already depressed because of gender inequalities, and so will not accurately value unpaid work [26]. A related argument is that the market “accepts existing sex/gender divisions of labor and pay inequalities as normal and unproblematic. With this basic assumption underlying their calculations, the valuations produced serve to reinforce sex/gender inequalities rather than challenge women's subordination” [25].

Criticisms are also leveled against the separate methods of valuation. Opportunity cost method “depends on the lost earnings of the worker so that a toilet cleaned by a lawyer has much greater value than one cleaned by a janitor” [25], which means that the value varies too drastically. There are also issues with the uniformity of this method not just across multiple individuals, but also for a single person: it “may not be uniform across the entire day or across days of the week” [26]. There is also the issue of whether any enjoyment of the activity should be deducted from the opportunity cost estimate [26].

Replacement cost method also has critiques, such as what types of jobs should be used as substitutes. For example, should childcare activities “be calculated using the wages of daycare workers or child psychiatrists?” [26]. This also relates to the issue of depressed wages in female-dominated industries, and whether using these jobs as an equivalent leads to the undervaluing of unpaid work. Some have argued that education levels should be comparable, for example, “the value of time that a college- educated parent spends reading aloud to a child should be ascertained by asking how much it would cost to hire a college-educated worker to do the same, not by an average housekeeper’s wage” [21].

Critiques against the input-output methods include: the difficulty of identifying and measuring household outputs and the issues of variation of households and these effects [26].

Notes[edit]

- ^ Beneria, Lourdes, Ann Mari May and Diana Strassmann, "Introduction" in Lourdes Beneria, Ann Mari May and Diana Strassmann, eds., 'Feminist Economics: Volume 1'. Cheltenham, UK and Northhampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, 2011.

- ^ Ferber, M.A. and Julie A. Nelson, "Beyond Economic Man: Ten Years Later," in Marianne A. Ferber and Julie A. Nelson, eds., Feminist Economics Today: Beyond Economic Man. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- ^ England, Paula, "The Separative Self: Androcentric Bias in Neoclassical Assumptions" in Lourdes Beneria, Ann Mari May and Diana Strassmann, eds., 'Feminist Economics: Volume 1'. Cheltenham, UK and Northhampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, 2011.

- ^ Ferber, M.A. and Julie A. Nelson, "Beyond Economic Man: Ten Years Later," in Marianne A. Ferber and Julie A. Nelson, eds., Feminist Economics Today: Beyond Economic Man. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- ^ Ferber, M.A. and Julie A. Nelson, "Beyond Economic Man: Ten Years Later," in Marianne A. Ferber and Julie A. Nelson, eds., Feminist Economics Today: Beyond Economic Man. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- ^ Peterson, Janice and Margaret Lewis, The Elgar Companion to Feminist Economics. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 1999.

- ^ http://www.facstaff.bucknell.edu/gschnedr/FemPrcpls.htm#_ftn1

- ^ http://www.facstaff.bucknell.edu/gschnedr/FemPrcpls.htm#_ftn1

- ^ Strassman, Diana. "Editorial: Expanding the Methodological Boundaries of Economics." Feminist Economics 3 (2), 1997, vii-ix.

- ^ Mankiw, N. Gregory. Principles of Economics. Fort Worth: Dryden Press, Harcourt Brace College Publishers, 1998

- ^ http://www.facstaff.bucknell.edu/gschnedr/FemPrcpls.htm#_ftn1

- ^ http://www.facstaff.bucknell.edu/gschnedr/FemPrcpls.htm#_ftn1

- ^ http://www.facstaff.bucknell.edu/gschnedr/FemPrcpls.htm#_ftn1

- ^ Matthaie, Julie. "Why Feminist, Marxist and Anti-Racist Economists Should be Feminist--Marxist--Anti-Racist Economists." Feminist Economics, 2 (1), 1996, 22-42.

- ^ http://www.facstaff.bucknell.edu/gschnedr/FemPrcpls.htm#_ftn1

- ^ http://www.facstaff.bucknell.edu/gschnedr/FemPrcpls.htm#_ftn1

- ^ Mankiw, N. Gregory. Principles of Economics. Fort Worth: Dryden Press, Harcourt Brace College Publishers, 1998.

- ^ Alkire, S. (2002). Valuing Freedoms: Sen's Capability Approach and Poverty Reduction. (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

- ^ Sen, Amartya. (1989). Development as Capability Expansion. Journal of Development Planning 19: 41–58, reprinted in Sakiko Fukuda-Parr and A.K. Shiva Kumar, eds. 2003. Readings in Human Development, pp. 3–16. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Carmichael, Fiona, Claire Hulme, Sally Sheppard, and Gemma Connell. “Work-Life Imbalance: Informal Care and Paid Employment in the UK.” Feminist Economics 14.2 (2008): 3-35.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Folbre, Nance. 2006. “Measuring Care: Gender, Empowerment, and the Care Economy.” Journal of Human Development 7(2): 183-99.

- ^ Philipps, Lisa. "Silent Partners: The Role of Unpaid Market Labor in Familis." Feminist Economics 14.2 (2008): 37-57.

- ^ http://unstats.un.org/unsd/nationalaccount/docs/SNA2008.pdf

- ^ Beteta, Hanny Cueva. “What is missing in measures of Women’s Empowerment?” Journal of Human Development 7.2 (2006): 221-241. EconLit. Web. 25 Feb. 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Luxton, Meg. “The UN, Women, and Household Labor: Measuring and Valuing Unpaid Work.” Women’s Studies International Forum 20.3 (1997): 431-439.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Mullan, Killian. “Valuing Parental Childcare in the United Kingdom.” Feminist Economics 16.3 (2010): 113-139.

Further Reading[edit]

Carrasco, Cristina, and Màrius Domínguez. “Family Strategies for Meeting Care and Domestic Work Needs: Evidence from Spain.” Feminist Economics 17.4 (2011): 159-188.

Jenkins, Katy. “We have a lot of goodwill, but we still need to eat…”: Valuing Women’s Long Term Voluntarism in Community Development in Lima.” Voluntas 20 (2009): 15-34.

Schüler, Dana. “The Uses and Misuses of the Gender-related Development Index and Gender Empowerment Measure: A Review of the Literature.” Journal of Human Development 7.2 (2006): 161-181.

Warren, Tracey, Gillian Pascall, and Elizabeth Fox. “Gender Equality in Time: Low-Paid Mothers’ Paid and Unpaid Work in the UK.” Feminist Economics 16.3 (2010): 193-219.

The formal economy[edit]

Research into the causes and consequences of occupational segregation, the gender pay gap, and "glass ceiling" phenomena have been a significant part of feminist economics. While conventional neoclassical economic theories of the 1960s and 1970s explained these as the result of free choices made by women and men who simply had different abilities or preferences, feminist economists pointed out the important roles played by stereotyping, sexism, patriarchal beliefs and institutions, sexual harassment, and discrimination.[1] The rationale for, and the effect of, anti-discrimination law, adopted in many industrial countries beginning in the 1970s, has also been a topic of research.[2] Women did, in fact, move in large numbers into previous male bastions (especially professions such as medicine and law) during the last decades of the 20th century.

While overt employment discrimination by sex per se remains a concern of feminist economists, in recent years more attention has also been paid to discrimination against caregivers—those women, and some men, who give hands-on care to children or sick or elderly friends or relatives. Because many business and government policies were designed to accommodate the "ideal worker" (that is, the traditional male worker who had no such responsibilities) rather than caregiver-workers, inefficient and inequitable treatment may result.[3]

Gender, race, class[edit]

Feminist economics attempts to not only examine women’s issues in economics, but to also examine the issues of as many other different groups of people as possible. No classification of people can ever capture every element at work, but by explicitly considering gender, race, class, and caste this can be improved upon.[4]

Globalization[edit]

Feminist economists argue that economic development in the Global South depends in large part on improved reproductive rights; gender equitable laws on ownership and inheritance; and policies that are sensitive to the number of women in the informal economy.[5]

Methodology[edit]

Interdisciplinary data collection[edit]

Many feminist economists challenge the perception that only "objective" (often presumed to be quantitative) data are valid. Instead, feminist economists suggest that economists should enrich their analysis through the use of data sets generated from other disciplines. Additionally, many feminists economics propose utilizing non-traditional data collection strategies.

Ethical judgment[edit]

This is a methodology that looks at systems not from the point of view of neutral observer, but from a specific moral position and viewpoint. Notably, the intention is not to create a more "subjective" methodology, but to counter-weight perceived biases in existing methodologies: By recognizing that all views of the world arise from viewpoints, it sheds light on what feminist economists claim are masculine biases. According to feminist economists, too many theories, while claiming to present universal principles, actually present a masculine viewpoint in the guise of a "view from nowhere."[6]

Alternative measures of success[edit]

Human development index[edit]

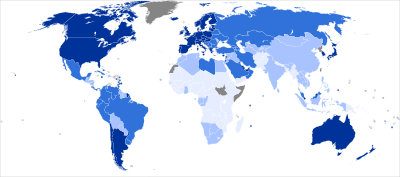

Very High (developed country) | Low (developing country) |

High (developing country) | Data unavailable |

Medium (developing country) |

Feminist economists often support use of the human development index as a composite statistic in order to assess countries by overall level of human development, as opposed to other measures. The HDI takes into account a broad array of measures beyond monetary considerations including life expectancy, literacy, education, and standards of living for countries worldwide. [7]

Organizations[edit]

Feminist economics is gradually becoming a widely recognized and reputed area of inquiry as evidenced by the numerous organizations either dedicated to feminist economics or widely influenced by its principles.

International Association for Feminist Economics[edit]

Formed in 1992, the International Association for Feminist Economics (IAFFE), is independent of the American Economic Association (AEA) and seeks to challenge the masculine biases in neoclassical economics[8]. While the majority of members are economists, it is open "not only to female and male economists but to academics from other fields, as well as activists who are not academics" [9] and currently has over 600 members in 64 countries. [10]. Although its founding members were mostly based in the US, a majority of IAFFE's current members are based outside of the US.In 1997, IAFFE gained Non-Governmental Organization status in the United Nations.

Feminist Economics journal[edit]

In 1997, the journal Feminist Economics was awarded the Council of Editors and Learned Journals (CELJ) Award as Best New Journal. The 2005 ISI Social Science Citation Index ranked the journal Feminist Economics 20th out of 175 among economics journals and 2nd out of 27 among Women's Studies journals.

Relation to other disciplines[edit]

Green economics incorporates ideas from feminist economics and Greens[who?] list feminism as an explicit goal of their political measures, often seeking higher valuations for such work. Feminist economics is also often linked with welfare economics or labour economics, since it emphasizes child welfare, and the value of labour in itself, as opposed to production for a marketplace, the focus of classical economy.

See also[edit]

- Notable feminist economists

- Gender equality, or gender equity

- Gender mainstreaming

- Intra-household bargaining

- Material feminism

- Time use

External links[edit]

- International Association for Feminist Economics (IAFFE)

- Feminist Economics (peer-reviewed journal)

Literature[edit]

- Agarwal, Bina. A Field of One's Own: Gender and Land Rights in South Asia. Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Barker, Drucilla K. and Susan F. Feiner. Liberating Economics: Feminist Perspectives on Families, Work, and Globalization. University of Michigan Press, 2004.

- Barker, Drucilla and Edith Kuiper. Toward a feminist philosophy of economics. Routledge, 2003.

- Lourdes Benería. Gender, Development, and Globalization: Economics as if All People Mattered. New York: Routledge, 2003.

- Ferber, Marianne A. and Julie Nelson (eds.).Beyond economic man: feminist theory and economics. The University of Chicago Press, 1993.

- Ferber, Marianne A. and Julie A. Nelson (eds.). Feminist Economics Today: Beyond Economic Man. The University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- Jacobsen, Joyce. The Economics of Gender. Wiley-Blackwell, 2007.

- Nelson, Julie. Feminism, Objectivity and Economics. Routledge, 1996.

- Peterson, Janice and Margaret Lewis (eds.) The Elgar Companion to Feminist Economics.Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd., 1999.

- Power, Marilyn. "Social Provisioning as a Starting Point for Feminist Economics" Feminist Economics. Volume 10, Number 3. Routledge, November 2004

- Sen, Amartya. Development as Freedom. Anchor Books, 1999.

- Waring, Marilyn. 1989. If Women Counted: A New Feminist Economics. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-49262-5

Graduate programs offering study in feminist economics[edit]

A small, but growing number of graduate programs around the world offer courses and concentrations in feminist economics. (Unless otherwise noted below, these offerings are in departments of economics.)

- American University

- School of Public Policy and Administration at Carleton University

- Colorado State University

- Institute of Social Studies

- Gender Institute of the London School of Economics

- Makerere University

- University of Massachusetts-Amherst

- The Masters in Applied Economics and Public Policy programs at the University of Massachusetts-Boston

- University of Nebraska-Lincoln

- The New School for Social Research

- University of Reading

- Roosevelt University

- Department of Women's and Gender Studies at Rutgers University

- Discipline of Political Economy at the University of Sydney

- University of Utah

- Wright State University

- York University (Toronto)

References[edit]

- ^ e.g., Bergmann, Barbara, Occupational segregation, wages and profits when employers discriminate by race or sex, Eastern Economic Journal 1 (2/3), 103-10, 1974. See also male-female income disparity in the United States.

- ^ Beller, Andrea H., 1982, Occupational Segregation by Sex: Determinants and Changes, The Journal of Human Resources 17(3): 371-392, 1982; Bergmann, Barbara In Defense of Affirmative Action, New York: Basic Books, 1996.

- ^ Waldfogel, Jane, “The Effect of Children on Women’s Wages,” American Sociological Review, 62: 209–17, 1997; Albelda, Randy, Sue Himmelweit, and Jane Humphries, 2004, "A special issue on lone mothers," Feminist Economics 10(2), 2004; Williams, Joan, Unbending Gender: Why Family and Work Conflict and What to Do About It, Oxford University Press, 2001.

- ^ Brewer, Rose M., Cecilia A. Conrad and Mary C. King, eds. 2002. A special issue on gender, color, caste and class. Feminist Economics, 8 (2).

- ^ Benería, Lourdes, Gender, Development, and Globalization: Economics as if People Mattered. London: Routledge, 2003

- ^ Nelson, Julie, Feminism, Objectivity and Economics, Routledge, 1996.

- ^ Fukuda-Parr, Sakiko (2003). "The Human Development Paradigm: operationalizing Sen’s ideas on capabilities". Feminist Economics 9 (2–3): 301–317.

- ^ Ferber, M.A. and Julie A. Nelson, "Beyond Economic Man: Ten Years Later," in Marianne A. Ferber and Julie A. Nelson, eds., Feminist Economics Today: Beyond Economic Man. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- ^ Ferber, M.A. and Julie A. Nelson, "Beyond Economic Man: Ten Years Later," in Marianne A. Ferber and Julie A. Nelson, eds., Feminist Economics Today: Beyond Economic Man. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- ^ http://www.iaffe.org/pages/about-iaffe/history/

Category:History of economic thought, methodology, and heterodox approaches

Category:Feminism and social class