Wikipedia:Reference desk/Archives/Humanities/2011 September 22

| Humanities desk | ||

|---|---|---|

| < September 21 | << Aug | September | Oct >> | September 23 > |

| Welcome to the Wikipedia Humanities Reference Desk Archives |

|---|

| The page you are currently viewing is an archive page. While you can leave answers for any questions shown below, please ask new questions on one of the current reference desk pages. |

September 22[edit]

British Empire & Colonies[edit]

Obviously there were many reasons for the British Empire to have colonies around the world, defence, trade etc

My question is - Did colonies pay taxes to Britain or did Britain subsidise these colonies?

And if taxes were paid, when did this process end? - I find it very unlikely that Hong Kong would have still been paying up until the hand-over in 1997!

I have read the articles on the History of the British Empire, Hong Kong & Singapore, but I can find no information on whether these colonies paid taxation to Britain.

And just exactly how much control did Britain have over these colonies? - in 1983, when the Hong Kong dollar was pegged to the US dollar, why wouldn't Britain have stipulated it should be pegged to Sterling (like other colonies, such as Gibraltar etc) — Preceding unsigned comment added by Jaseywasey (talk • contribs) 08:33, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- I can’t speak for other colonies, but Hong Kong has not paid taxes to the UK ever, to the best of my knowledge. In fact, it was the other way around: military forces in HK were paid for by the UK.

- How much control did the UK have? Lots. The HK Governors, like the Chief Executive today, has a much larger degree of power than prime ministers or presidents in most democracies, and because they are appointed by the UK, they generally had to give at least outward support to British policy preferences (but, not always: see John James Cowperthwaite for an example of a financial secretary who wasn’t about to introduce the welfare state to Hong Kong).

- Finally, the peg. Fixed exchange rates, particularly for small, open economies, are best fixed to the currency in which the largest share of trade is conducted. That has been the US dollar for many decades. DOR (HK) (talk) 09:34, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- It varies a lot. The North American colonies famously paid taxes. Imperial India paid tax, and was a market for British goods, while its products and riches were taken under less than scrupulous conditions. Other colonies are still kept for their military value, and therefore will be subsidised if necessary (South Atlantic territories like Tristan da Cunha are obvious examples, although today there is the possibility of oil too - and Economy of the Falkland Islands says the Falklands do quite well if you discount defence spending). --Colapeninsula (talk) 13:14, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- Yes, many British colonies did pay tax - they were British as far as the Crown was concerned. In America and Australia, security and police forces, etc., were all provided by the UK (at first), so it only stands to reason that they should be paid for, and paid to the UK. India was a different story - that was merely occupation and force-feeding of British trade goods at high prices, whilst taking everything India had to offer, and then charging tax. As we all know, Britannia waives the rules..... KägeTorä - (影虎) (TALK) 13:29, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

Of course there was No Taxation Without Representation - however I was thinking more of the colonies that achieved independence during the 20th Century - Before WW2, these smaller countries would have had the benefit of a super-power defence force, which may have kept ambitious neighbours in check. However after 1945, Britain was virtually bankrupt and poor third behind the USA & USSR in the military "pecking order".

It seems to me that, there WAS a benefit for countries such as Jamaica, (in fact any Caribbean nation), Malta, Singapore etc. - (HK is a slightly different case due to the 99-year lease). These nations had another country responsible for their military defence, but didn't have to pay any taxes?

Whilst I appreciate that most countries would prefer self-determination, I can see the logic for Britain happily allowing this to occur (one a stable, non-communist government was in-place). In fact I'm surprised that the UK didn't encourage independence for any non-strategic nations, with limited natural resources. Jaseywasey (talk) 15:03, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- Don't kid yourself. There are plenty of ways to bleed a colony dry without having to ask it to pay taxes. In fact, being merely taxed would have been a blessing in some cases. It was only when imperialism started getting bad rap that colonial powers started to put a little bit more effort into giving something back for their colonies. And even then, it was for the benefit of the colonial government, not the locals. Those defense forces you mentioned were not defense forces, but occupying forces meant to keep the locals in check, and yes they are expensive. In the WW2 example, colonial powers left their colonies to the mercy of the Japanese without much hesitation. The only real danger of invasion came from imperialists in the first place. -- Obsidi♠n Soul 15:24, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- "There are plenty of ways to bleed a colony dry without having to ask it to pay taxes" - like what? And why would the mother country want this? Riteota (talk) 15:35, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- Some of the many ways to do this include handing over land to companies and individuals from the parent country and allowing those companies and individuals to farm and mine that land without compensating the people who lived there and who owned it until it was forcibly taken from them. Why would the parent company want this? It enriched their citizens, it provided inexpensive supplies of strategic raw materials to the parent country, and so on. Another method is to sell manufactured goods from the parent country at an initial loss until the local manufacturing sector is weakened or destroyed, then to raise the price on these goods once the colony has become a captive market. Yet another method is to impose a monopoly on a key good needed by the local population and require them to buy this good from firms or individuals based in the parent country, for which this trade became a source of profit at the expense of the colony. Gandhi's Salt Satyagraha was aimed a such a practice. Marco polo (talk) 15:47, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- "There are plenty of ways to bleed a colony dry without having to ask it to pay taxes" - like what? And why would the mother country want this? Riteota (talk) 15:35, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- Why do you suppose so many colonies fought so fiercely for independence even if it meant economic collapse? Colonial powers ('mother countries', LOL) were not motivated by altruism. They were motivated by profit. They didn't give a rat's ass about the natives. Defensive armies, LOL. Indeed, to some, they were merely indigenous animals.-- Obsidi♠n Soul 16:05, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

Post-WW2, I don't recall many colonies fighting fiercely (except India, but not necessarily "fighting")

My initial question related to HK - as far as I can see this territory was a "net-gainer", albeit it meant that UK had a military base, right on China's doorstep.

But what about countries like Brunei, a British protectorate until 1984........in 1976 Jim Callaghan had to go "cap-in-hand" to the IMF for a loan to bail-out Britain, when the country was virtually bankrupt........the Sultan of Brunei was at that time the richest man in the world......do you see where I'm going here......? Jaseywasey (talk) 17:14, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- In this context, you might also puzzle why "the Government and people of the Federated Malay States" chose to contribute a vast sum of money to buy HMS Malaya for the Empire in 1913. --Demiurge1000 (talk) 18:25, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- Let me explain why all this is more than a little insulting to people who were once under colonial governments (like mine), and I'm not even nationalistic. You see, this isn't a new idea. In fact, it was the justification used for our second invasion - The White Man's Burden, when America caught the imperialism bug. It was quite brutal and extremely unscrupulous but largely forgotten or ignored in American history today. To claim that establishing colonies were motivated by altruism is more than a little outrageous. You can not merely ignore centuries of blatant exploitation and then claim that you protected them while they gave nothing back in the last decades of their exploitation. You can only justify that if you conveniently forget the events leading up to that situation in the first place. And yes, the UK did in fact encourage decolonization after their economic collapse after WW2. Partly because attempts to prevent it by other countries resulted only in more losses (like the First Indochina War).

- Protectorates/protected states were not freeloaders for much of their histories. They had economic importance to the protector. They were to be 'protected' (i.e. puppet governments established or commandeered) in exchange for serving as hosts to colonial economic interests (not merely as places for military bases). Brunei wasn't the tiny state that it is now. In fact, establishing a protectorate was the least Britain could do after they so much as stole an entire island from the Sultanate. See History of Brunei#Relations with Europeans and British Empire#Decolonisation and decline (1945–1997). -- Obsidi♠n Soul 18:26, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- I feel the need take Obsidian to task over his charge that the European powers left "their colonies to the mercy of the Japanese". The Dutch had two cruisers in the East, both were sunk at the Battle of the Java Sea. Like Britain, the NL only maintained sufficient forces for internal security in her Asian possessions. There was no backup as the rest of the Dutch army had been destroyed by the Germans. 1,300 defenders of Tarakan were all executed by the Japanese after they surrendered. 1,100 defenders of Balikpapan were all killed or captured. The same story repeated all over the Dutch East Indies. Britain and Australia poured troops into Singapore; 134,000 were killed or captured. 840 sailors were killed when a British naval task force was destroyed. Hong Kong, defended by a Canadian brigade, fought on for 2 weeks outnumbered 4 to 1. Not an effective defence but much blood was spilt in the effort. Alansplodge (talk) 19:15, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- I was talking specifically of Plan Dog memo. But yeah, that was understandable enough and I concede you have a point. Though I still do not see how it would prove Jaseywasey's assertion that the presence of colonial forces were intended primarily to provide defensive benefits for the territories involved at no cost to their subjects. They defended them, but that does not mean that was their reason for colonizing them in the first place.-- Obsidi♠n Soul 21:08, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- Yes I agree that empires were not there to protect the colonised; but it was the intention of the colonial powers to protect their colonies and the inhabitants of them, but it could not be realised in 1941/42. Thank you for drawing my attention to Plan Dog, however this was a US creation. Reading the war diaries of Alan Brooke, I get the impression that Britain hadn't fully appreciated the Japanese threat until it was too late to do anything but the rushed response that failed so miserably. Alansplodge (talk) 22:39, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- I was talking specifically of Plan Dog memo. But yeah, that was understandable enough and I concede you have a point. Though I still do not see how it would prove Jaseywasey's assertion that the presence of colonial forces were intended primarily to provide defensive benefits for the territories involved at no cost to their subjects. They defended them, but that does not mean that was their reason for colonizing them in the first place.-- Obsidi♠n Soul 21:08, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

I really hoped this wouldn't descend into an argument about the "rights & wrongs" of Imperialism. My main query related to post-WW2 HK - this country became very successful whilst Britain was virtually bankrupt. HK has famously low taxation, whilst in Britain during the 70's income tax reached 83% - I appreciate that after WW2, America was "anti-colonialism", however they did concede that the colonies prevented the spread of communism and were therefore tolerated. I think it is reasonable to say, due to a massive change in public opinion, colonies changed from "cash-cows" to financially independent states with increasing levels of autonomy and Britain realised that rather than being seen as assets, they were now liabilities (having the responsibility of defending countries that no longer "pay for themselves"), hence the policy of "peaceful disengagement" Jaseywasey (talk) 06:45, 23 September 2011 (UTC)

- I'm sorry, but the implications of this question itself is inflammatory. It's virtually repeating the colonial mentality that these territories were little more than, as you said, cash-cows that were to be taken advantage of, and once used up, thrown away. Brunei, itself, at the state that it had been reduced to due to British expansion into Malaya, wouldn't have been able to survive as a sovereign nation if it wasn't for the discovery of oil. Why would they be obligated to pay even more?

- The UK was honoring old treaties with both Brunei and HK. They couldn't simply throw them away and sever even more diplomatic ties already frayed by WW2. A move like that would have destroyed their credibility completely. The UK did, as already mentioned, let go what they can peacefully, even insisted on it (HK was supposed to be theirs for eternity). For what it's worth, British Overseas Territories are still notorious for being tax havens, notably Bermuda. As for control, see Crown colony.-- Obsidi♠n Soul 17:14, 23 September 2011 (UTC)

Palestinian state[edit]

Palestinian leaders are apparently going to ask the UN to declare Palestine a full UN member state, or something similar. Israel's public statement against this has been that the proper way to attain this goal is to continue peace negotiations with Israel; and that the UN is not the proper venue for this declaration.

Maybe I am missing something on this last point and someone could help. The UN was the exact venue by which Palestine was officially partitioned in the first place and the state of Israel was created. Isn't the Israeli claim (that the UN is not the right venue for this) hypocritical right on its face?

I obviously don't want to start a flame thread here and am not interested in the deeper arguments over the validity of either Israel or the Palestinian state, or who is in the right on this particular issue; I just object to an argument that is so easily countered. What am I missing? Riteota (talk) 15:33, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- While I am sympathetic with the Palestinian perspective on this issue and see no reason why they shouldn't declare their independence, I will confine myself to explaining the Israeli position. Israel's point is that declarations in the United Nations will not resolve the conflict, because they are not going to influence Israel's actions. (They haven't in the past; why should they now?) The only way for the Palestinians to change the facts on the ground is to engage directly with Israel. Actually, I think it's hard to dispute that, even if engagement with Israel hasn't improved the situation of Palestinians much in recent years, for reasons that are outside the scope of your question. Marco polo (talk) 15:42, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- Israel feels that the United Nations is not the proper forum in very large part because of the flagrant and widespread anti-Israel bias frequently displayed at the UN -- starting as early as 1961, when Israel was the only member country to be excluded from the UN regional groups that were created at that time, and which have become very important in the internal workings of the UN (Israel still only has provisional membership in WEOG in New York, but not in Geneva or Vienna), and intensifying markedly in 1975, and continuing through the annual ceremonial General Assembly "Two-Minutes-Hate-Against_Israel" meetings (which neither the United States nor Israel has bothered to even attend for many years) and on into the 2000s with the infamous 2001 Durban conference for the promulgation and promotion of racism and the apparently very intentional and deliberate decisions among high UN officialdom to maliciously appoint individuals to prominent middle-east relevant positions such as Cornelio Sommaruga and Richard Falk who are personally completely unacceptable to Israel. The United Nations Commission on Human Rights was abolished in significant part because of its extravagantly flamboyant brazen flagrant hypocrisies (many having to do with Israel), but its successor, the United Nations Human Rights Council, really hasn't done much better... AnonMoos (talk) 18:44, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- P.S. See Durban III for something going on right now which 14 countries (including the United States) have boycotted over fears that it will devolve into an officially UN-sponsored anti-Israel hatefest (with antisemitic overtones)... AnonMoos (talk) 19:09, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- Being in conflict is not a valid reason to disqualify a country from UN membership. Under such a guideline the USA would never have qualified. Saying the UN shouldn't have a say because you don't like the way it votes is like an American state saying the Senate shouldn't have a say for the same reason. HiLo48 (talk) 20:45, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- A more sensible comparison would be the Libyan transitional government, which is intervening in an "internal" affair of the Libyan state. In that case, though, like the switch from recognition of Republic of China vs. People's Republic of China, those are a "one for one" swap instead of a "one for two" swap. The UN doesn't have much authority in the internal affairs of its members, and there are probably odd questions about how occupied territories are handled. Given that Israel more or less ignores the UN anyway (for reasons stated above), the Palestinians appealing to the UN doesn't make much difference. The UN doesn't authority beyond trying to convince its members, and the actual powers either support Israel in the dispute (e.g. the US) or haven't shown much interest in getting involved (e.g. China). Even China might quietly oppose this, since they don't want Taiwan getting any ideas about methods for declaring independence. SDY (talk) 22:47, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- AnonMoos has answered this question eloquently. I think it's also worth pointing out that the circumstances are quite different from 1947. Back then, the UN was suggesting what to do with the Palestine Mandate after its approaching expiration. The plan was rejected by the Arabs, and in the end Israel won its independence on the battlefield. Today, all sides theoretically support the concept of a Palestinian state; the question is how it should happen. -- Mwalcoff (talk) 23:23, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- A more sensible comparison would be the Libyan transitional government, which is intervening in an "internal" affair of the Libyan state. In that case, though, like the switch from recognition of Republic of China vs. People's Republic of China, those are a "one for one" swap instead of a "one for two" swap. The UN doesn't have much authority in the internal affairs of its members, and there are probably odd questions about how occupied territories are handled. Given that Israel more or less ignores the UN anyway (for reasons stated above), the Palestinians appealing to the UN doesn't make much difference. The UN doesn't authority beyond trying to convince its members, and the actual powers either support Israel in the dispute (e.g. the US) or haven't shown much interest in getting involved (e.g. China). Even China might quietly oppose this, since they don't want Taiwan getting any ideas about methods for declaring independence. SDY (talk) 22:47, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

Two simple equations: Israel + Palestine + uninvolved people = shit ton of drama. Israel + Palestine + uninvolved people + Internet = (shit ton of drama)3. I am saying out of what will inevitably become a long drawn-out, annoying and (in the end) pointless debate. Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie | Say Shalom! 23:36, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- Your equations as written are unsolvable, which is what I should have expected. Googlemeister (talk) 13:42, 23 September 2011 (UTC)

- Oh my, I do hope that wasn't meant to be something uncivil.

Well, if you want to get pedantic about it, what would that be as it is not meant to be solved? Solution? Formula? Law? Something else? I forget the terminology; was just going by connotation to tell you the truth.

Well, if you want to get pedantic about it, what would that be as it is not meant to be solved? Solution? Formula? Law? Something else? I forget the terminology; was just going by connotation to tell you the truth.  Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie | Say Shalom! 25 Elul 5771 03:27, 24 September 2011 (UTC)

Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie | Say Shalom! 25 Elul 5771 03:27, 24 September 2011 (UTC)

- Oh my, I do hope that wasn't meant to be something uncivil.

- This video is a must-see for anyone interested in the history of the Israel-Palestine conflict. 67.169.177.176 (talk) 20:44, 23 September 2011 (UTC)

You are correct, it is hypocritical, and it is easily countered, the reason they chose this excuse for trying to stop the UN recognizing Palestine is it was the best they could come up with. Israel fears Palestine with have greater access to world courts and that there would be no doubt that Israel is breaking numerous international laws, such as relocating Israelis into foreign territory(no more doubt that it's foreign as another UN nation controls it). Try and come up with a better excuse to stop the UN from recognizing a nation that the majority of UN nations already recognize, there are no good excuses, so they came up with the garbage you pointed out. Seems like everyone but Marco Polo failed to answer your question. The other excuse I've heard of "the United Nations is not the proper forum" is also an equally stupid excuse to try to derail recognition and continue the occupation. Public awareness (talk) 07:04, 24 September 2011 (UTC)

The illegitimate children of noblewomen[edit]

What was the status of the illegitimate children of female members of the nobility? This is an historical question and refers to Europe pre-1900. It is not very hard to acquire information about the illegitimate children of noblemen, but it is harder to confirm such children of noblewomen. The former was perfectly acceptable, while the latter was considered a disgrace and hidden. This is of course about unmarried noblewomen, as the children of a married woman were assumed to be the children of her husband.

What I wonder about is: did such children count as nobles? The situation was after all different. Illegitimate children to noblemen could be acknowledged or not by their noble father, while the illegitimate children of a noble mother were undoubtedly her children.

If both the parents of illegitimate children were noble, did the children count as noble? If the mother were noble and the father not, did the children count as noble?

The question above, I suppose, is rather of a legal kind, but I also wonder about the place of these children in the social attitude of people. Which social position did they have? Did the attitude toward them differ in any way from the attitude to illegitimate children of male nobles?

I have the impression, that illegitimate children of two nobles were treated fairly well, better than illegitimate children of male nobles and non-noble women. It also seem to me, that illegitimate children of noblewomen and non-noble men were in fact treated somewhat better, when it comes to social attitude, than did illegitimate children of male nobles and non-noble women. Perhaps because there was never any question as to whether they belonged to the family, while a noble father could always deny them? But this is just an impression. I realize this is a difficult question. Thanks! --85.226.43.106 (talk) 16:41, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- An interesting question to this is also: which name was the child given? The illegitimate child of a nobleman could be given his name if he acknowledged the child. Was the illegitimate child of a noblewoman automatically given her noble name, because she could no deny it as hers? And could the child have a noble name without being considered noble?--Aciram (talk) 17:00, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- Sometimes, a name may be invented for them. The last name Fitzroy (Anglo-Norman for "Son of the King) was frequently given to illegitimate sons of various English kings, borne most often by noblewomen (because they were who was availible to have illegitimate fun with). --Jayron32 17:04, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- But those were the children of noble/royal males as well. My question is about illegitimate children of noble females, in particular to children of noblewomen and fathers of the same or lower status than the mother. --85.226.43.106 (talk) 17:29, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- @Jayron32, I do not think royal men were restricted to only noblewomen to have illegitimate sex with: royal men could perhaps only have noblewomen as their official mistresses, but they could surely have sex with as many female servants and peasant girls as they wished, although this was not recognized and the children in those case were not as often acknowledged. What you say about the name is true, but what would be the case of a name for a noblewoman and a male servant? Did the child get her surname? The name "Son of the King" also describe the child's father as the high status parent, so therefore that case is more about the father than the mother. If it was the mother who had the higher status, then what?--Aciram (talk) 17:33, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- @Aciram: Please be aware that the phrase "most often" is not identical to the word "always". It appears, from your response, that you didn't recognize the difference. I will concede that a better word may have been "sometimes". But I did not imply in any way that Kings didn't do the deed to non-noble people as well. --Jayron32 17:42, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- @Jayron32, I do not think royal men were restricted to only noblewomen to have illegitimate sex with: royal men could perhaps only have noblewomen as their official mistresses, but they could surely have sex with as many female servants and peasant girls as they wished, although this was not recognized and the children in those case were not as often acknowledged. What you say about the name is true, but what would be the case of a name for a noblewoman and a male servant? Did the child get her surname? The name "Son of the King" also describe the child's father as the high status parent, so therefore that case is more about the father than the mother. If it was the mother who had the higher status, then what?--Aciram (talk) 17:33, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- At common law, there was no operation to legitimize a child other than by act of parliament. I provide a quotation form Lord William Blackstone on bastards, writing in the middle of the 18th Century and reflecting upon the law as it existed during the reign of Richard II of England:

I proceed next to the rights and incapacities which appertain to a bastard. The rights are very few, being only such as he can acquire; for he can inherit nothing, being looked upon as the son of nobody; and sometimes called filius nullius, sometimes filius populi. Yet he may gain a sirname by reputation, though he has none by inheritance. All other children have their primary settlement in their father’s parish; but a bastard in the parish where born, for he hath no father…The incapacity of a bastard consists principally in this, that he cannot be heir to any one, neither can he have heirs, but of his own body; for being nullius filius, he is therefore of kin to nobody, and has no ancestor from whom any inheritable blood can be derived. A bastard was also, in strictness, incapable of holy orders; and, though that were dispensed with, yet he was utterly disqualified from holding any dignity in the church: but this doctrine seems now obsolete; and, in all other respects, there is no distinction between a bastard and another man. An really any other distinction, but that of not inheriting, which civil policy renders necessary, would with regard to the innocent offspring of his parents’ crimes, be odious, unjust, and cruel to the last degree: and yet the civil law, so boasted of for its equitable decisions, made bastards, in some cases, incapable even of a gift from their parents. A bastard may, lastly, be made legitimate, and capable of inheriting, but the transcendent power of an act of parliament, and not otherwise: as was done in the case of John of Gant’s bastard children, by statute of Richard the second. (italics in the original)

- Both England and the United States reformed these laws finding they were unfair and with the later, a violation of equal protection under the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. What has endured into modern times is the irrebutable presumption that a child born of a marriage is the legitimate child of the marriage. As of 2011, a man claiming to be the father of a child born in a marriage cannot sue for a paternity test and custody, even if the parents later divorce after the child is born. In quoted text above, filius nullius means "son of no one," filius populi is "son of the people." There was no adoption at common law except by statute, but the practice existed in Rome. As you can see from the passage, the law protected one's birthright. You can imagine the chaos that could errupt if an arranged marriage produced illigitimate offspring when the families had intended that their properties be divided or united in a particularly way. The law did not provide for a distinction among illigitimate children based on the status of the parent, male or female, unless of course, it was the King making the rules as was the case with Richard II. Gx872op (talk) 18:07, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- That was very helpful, and it answers the legal part of the question, at lest when England is concerned. Thank you! Was it the same way in the rest of Europe, such as France and the Holy Roman Empire?

- The other part of my question, however, is more a question about social attitude rather than law. It seem to me that "bastards" of women, that it to say children of noblewomen and men of the same or lower rank, were regarded in a somewhat different way than the when the man was noble. Did the sight upon them differ within society? No illegitimate children may have been legally noble, but which status did they have informally, when it came to the attitudes of society? Did the illegitimate child of a noblewoman get to use her surname? Are there any examples of illegitimate children of noblewomen? And I am referring to noblewomen rather than royal women. this question is truly very interesting. --85.226.43.106 (talk) 20:38, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

Why are the states of Alaska and Hawaii usually ignored?[edit]

Many U.S maps and U.S maps that appear on TV completely leave out Alaska and Hawaii as if they weren’t part of the U.S. The Weather Channel, the meteorologists of the major American news outlets, and the meteorologists of news outlets oversees (I’ve been overseas enough times to notice it), only give the weather of the 48 contiguous states, but they always ignore Alaska and Hawaii. The American news media and the worldwide media only report the news about what’s going on in the 48 contiguous states, but the exceptions are when Obama goes to Hawaii and if Sarah Palin goes to Alaska. As a result of the lack of attention that Hawaii and Alaska are receiving, many people around the world and even many Americans don’t have a basic understanding of these 2 states. I actually know a friend of a friend who went to Alaska years ago and all the time he was there he was looking around for some currency exchange place to exchange his dollars to whatever he thought Alaska’s currency was. Later, he found out that Alaska is a U.S state after his friends made fun of him. I found out that this kind of stuff, plus other stuff, seems to be quite common. I came across an eye opening thread that was started by an Alaska resident who complained about the same thing I’m asking about. Why are the states of Alaska and Hawaii usually ignored? Would be correct to call them “the forgotten states” of America? Willminator (talk) 17:19, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- Alaskan residents also get a little pushy when you use the term "CONUS" to mean "Continental United States" instead of "Contiguous United States." The "otherness" of AK and HI is even enshrined in US government policy, with both of these states treated in some administrative capacities as territories. For example, per diem rates in AK and HI are set by the Department of Defense rather than the General Services Administration. It's probably a legacy of administrative decisions made during WWII, which predated those two getting their stars on the flag. SDY (talk) 17:32, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- (edit conflict) Because they are discontiguous and some distance away from the rest of the U.S. Hawaii is almost as far from California as California is from the East Coast, while Alaska is so large that its extreme points are as far from each other as the extreme points of the "lower 48". Maps of France frequently ignore places like French Guiana and Réunion despite the fact that the relationship between those places and Metropolitan France is identical to the relationship between Alaska/Hawaii and the "lower 48" in the U.S. Many maps cram an out-of-scale map of both Alaska and Hawaii as insets into U.S. maps. For certain applications, like on the Weather Channel (which does cover Alaska and Hawaii as part of their regular round-up, I should say), including Alaska and Hawaii in their "national map" doesn't make much sense because the weather affecting the lower 48 often doesn't have any connection to that of Alaska and Hawaii; for various reasons you'd want such a map to be in scale (to show accurate, large scale weather patterns) and such a scale map would be impractical, to say the least. As far as Americans not understanding their own geography, it is a well documented problem which is not at all limited to Alaska and Hawaii. I come from New Hampshire, which I can confirm that many people from other parts of the country don't know exists, or if they do, don't know its a state. And it's on all the maps.--Jayron32 17:37, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- (EC)Per recent discussion on the Ref Desk talk page, when a question contains a false premise, and has the potential to become a debate, the thread should probably be preemptorily closed as was another recent thread. Do you have references discussing this phenomenon, or screen captures, or Youtube links? Here is a map from CBS News which shows all 50 states. Here is a map from NBC news which shows all 50 states. Here is a Fox News map showing all 50 states.Here is a CNN map showing all 50 states. Sometimes they tuck the last two states in the lower left corner. If a map relates to something which only happens in the old 48, then it might make sense to only show those states. Edison (talk) 17:41, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- Edison, I did not say that Alaska and Hawaii never appear in U.S maps, I only said that in many of the U.S maps I've seen these states don't appear at, not even in the lower left corner. That's what I've observed. Edit: Here's one example, here's another, and another. Willminator (talk) 18:10, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- Your first example. "Mrs. Fralish's class" has a lot of links. Do you seriously expect the Ref Desk volunteers to defend or to explain the choices of some obscure school teacher from "Auburn High School?" I would be embarrassed to detail all the ways in which my own high school teachers were ignorant. Which particular one of the links supports your premise? It looks irrelevant to your complaint about "Many US maps" in general or "US maps on TV." Number 2 is similarly just "Wired science," which few have ever heard of. Number 3 is also an obscure site. Collapse this thread. Edison (talk) 03:53, 23 September 2011 (UTC)

- Edison, I did not say that Alaska and Hawaii never appear in U.S maps, I only said that in many of the U.S maps I've seen these states don't appear at, not even in the lower left corner. That's what I've observed. Edit: Here's one example, here's another, and another. Willminator (talk) 18:10, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- Alaska and Hawaii are the 47th and 40th US states in order of population size. How often do you here about things happening in the other states that small and smaller? (ie. Maine, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Montana, Delaware, South Dakota, North Dakota, Vermont and Wyoming) --Tango (talk) 17:51, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- Combined, Alaska and Hawaii account for 0.67% of the US population and they are polar opposites in political matters. Add to the fact that they are more then 1,000 miles away from the rest of the US, and the results should not be surprising. I mean, how often do you hear about the Kaliningrad Oblast on major Russian news? Googlemeister (talk) 18:23, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- I can hardly think you can consider them "forgotten states." Everyone knows that they're there, and what they're about. (Hawaii: small; islands; beautiful; surfing. Alaska: gigantic; wilderness; cold; bears.) Every American schoolchild can find them on maps if they're there. Contrast that with West Virginia, South Dakota, Montana, or Wyoming. I suspect most American adults can't identify Wyoming on a map. Which capital city do you think is better well known, Honolulu or Cheyenne? It's true that Hawaii and Alaska get bumped from representations of the contiguous US, and are not considered to be quite as "normal" as the contiguous US (they aren't really manifest destiny states, they're extras that were acquired by the by), but they are far, far more represented in American culture and politics than many other states. --Mr.98 (talk) 19:34, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- If you go by the weather maps that appear on the typical TV news program here in the lower 48, all weather systems miraculously disappear once they hit the Canadian boarder. This striking meteorological phenomenon apparently works the other way on TV weather maps in Canada... According to CBC, the US never has any weather. Blueboar (talk) 19:41, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- Yes, and this is particularly annoying in places where the weather comes from Canada, like in Buffalo, NY. StuRat (talk) 20:44, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- I think both states get news coverage. Alaska for Sarah Palin and oil related issues, not to mention the "bridge to nowhere", while Hawaii is often in the news for Obama's time growing up there, and Congressional junkets there at taxpayer expense. StuRat (talk) 20:50, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

For those who pay any attention at all, the fact that Alaska and Hawaii do get mentioned separately from the continental USA all the time means that more people do at least know of their existence, and roughly where they are, than the number who would know of those earlier mentioned little states. Exactly where IS Wyoming? HiLo48 (talk) 08:21, 23 September 2011 (UTC)

A quick check searching some states on Google News:

- Connecticut returns "About 23,800 results"

- Oregon returns "About 20,100 results"

- Utah returns "About 19,900 results"

- Nebraska returns "About 17,600 results"

- Alaska returns "About 17,100 results"

- "West Virginia" returns "About 16,700 results"

- Hawaii returns "About 16,100 results"

- "New Hampshire" returns "About 15,600 results"

- Wyoming returns "About 12,700 results"

- Vermont returns "About 12,600 results"

- "Rhode Island" returns "About 8,960 results"

- "North Dakota" returns "About 7,800 results"

- "South Dakota" returns "About 6,910 results"

--Colapeninsula (talk) 09:54, 23 September 2011 (UTC)

- However, news on TV, radio or in print is heavily biased towards local stories, so that, if the OP was in Florida, then maybe 50% of the stories would be about Florida, 20% about the South, 20% about DC, and 10% about the rest of the nation, with Alaska and Hawaii getting a small slice of that 10%. You might get slightly more Alaska stories in Washington state and Hawaii stories in California, but, since neither is particularly close, it might not make all that much difference. StuRat (talk) 04:02, 24 September 2011 (UTC)

Was Feudalism bad?[edit]

There is this atheist show (I'm an atheist myself), and in it, a caller asked the hosts what they thought about Buddhism. They didn't really have much to say about it, but one host said that in the past there were Buddhist feudal lords living in Tibet. It got me thinking, well... so what? What's wrong with that? ScienceApe (talk) 19:29, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- Well, there were various kinds of feudalism. Western European is the best known, and Japanese feudalism was apparently very similar. Tibetan society is another matter, and there's less research into it, at least less that is available in English. One thing that is common to most societies that can be called feudal is that there was a vast gap between the powerful elite and the majority. The elite, and these would be the Buddhist lords in this case, did little or no work, while the majority of people toiled long hours in agriculture. Itsmejudith (talk) 19:44, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- Well, serfdom is a form of slavery, for one thing. That's usually the main complaint about feudalism. What that has to do with Buddhism, I don't know. Maybe they were trying to point out that Buddhism is not always about peace, love, and the Yin-Yang? I don't know. It's not a very compelling argument. --Mr.98 (talk) 19:39, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- That's what I was thinking. Most Japanese are Buddhist, but I don't think that had anything to do with the imperialistic nature they had before and during WW2. ScienceApe (talk) 19:52, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- It seems that they are closely tied together. "The vast majority of Japanese people who take part in Shinto rituals also practice Buddhist ancestor worship. However, unlike many monotheistic religious practices, Shinto and Buddhism typically do not require professing faith to be a believer or a practitioner, and as such it is difficult to query for exact figures based on self-identification of belief within Japan. Due to the syncretic nature of Shinto and Buddhism, most "life" events are handled by Shinto and "death" or "afterlife" events are handled by Buddhism—for example". But again I don't fault Shintoism for their imperialistic nature either, I don't think it had anything to do with it. ScienceApe (talk) 20:35, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- "Bad" is hard to give a definite answer to. It was a reasonably efficient way to organize an agricultural society, though the people at the bottom were basically slaves, they at least nominally chose to swear an oath of fealty rather than simply being owned (assuming it worked like the European system). The amount of coercion involved probably invalidated any "choice." If the rulers chose that form of government because they wanted to exploit the people or just didn't care would be ethically problematic, if they simply weren't aware of a better way to do it or were just following tradition it's more complicated. They might have believed it was their moral obligation to rule in that fashion. I certainly wouldn't want to live that way, and it was "bad" in the sense that it was a pretty lousy way of life, but from an ethical standpoint it's more difficult to condemn. SDY (talk) 19:47, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- Agreeing with SDY, "bad" is very hard to define in any universal sense. I don't know what the show you were listening to was, but my guess was that the atheist was a secular humanist, while most secular humanists do not accept absolute morality, have an ethical view that humans have an intrinsic right to shape their own life. Personally I think this is more likely an out growth contemporary moral standards rather than a universal idea, but that is another story. Given the view point that people have a right to shape their own lives, feudalism comes across pretty bad, as has been said, it is near slavery for much of the population, very inequitable. From my point of view feudalism isn't really "bad," it is just the form of social relations that tends to emerge from a decentralized agrarian society. It happened all over the world independently and is actually pretty efficient at growing cereals without much central authority. Still it would suck to be a serf. --Daniel 20:21, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- Feudalism in its ideal form wasn't "bad" at all... in some ways it was quite altruistic. At the bottom of the pyramid there was a social contract between peasants and armed knights for mutual support in a dangerous and uncertain barter based economic world. The peasants provided goods (primarily food) in exchange for protection from invaders (whether rampaging barbarians, or rival lords). The knights and lords had responsibilities towards their peasants and vise-verse. As you move higher up the idealized pyramid, feudal society consisted of a network of mutual obligations between various lords and vassals ... the senior nobles (such as the king) offering land to live on, good laws and even handed justice in exchange for armed service and other defined duties from their vassals. Unfortunately, human nature being what it is, Feudalism rarely (if ever) existed in its true idealized form. Greed has a way of undoing most social contracts. Blueboar (talk) 20:29, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- As for the atheist show, you can find it here. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2pMOKj3hvY4&feature=channel_video_title at the 37:40 mark approximately. ScienceApe (talk) 20:39, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- Agreeing with SDY, "bad" is very hard to define in any universal sense. I don't know what the show you were listening to was, but my guess was that the atheist was a secular humanist, while most secular humanists do not accept absolute morality, have an ethical view that humans have an intrinsic right to shape their own life. Personally I think this is more likely an out growth contemporary moral standards rather than a universal idea, but that is another story. Given the view point that people have a right to shape their own lives, feudalism comes across pretty bad, as has been said, it is near slavery for much of the population, very inequitable. From my point of view feudalism isn't really "bad," it is just the form of social relations that tends to emerge from a decentralized agrarian society. It happened all over the world independently and is actually pretty efficient at growing cereals without much central authority. Still it would suck to be a serf. --Daniel 20:21, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- I've read some pretty horrendous things about girl serfs in pre-China Tibet. Imagine Reason (talk) 02:13, 23 September 2011 (UTC)

- OK, Buddhism and Shinto are not related in any way whatsoever. Going by what the simple people do is not a way to understand any religion. The Japanese will go to the buddhist temples to 'revere their ancestors', and go to a Shinto shrine to celebrate a new house being built. The same people will go to a fake chapel to have a 'wedding' done by an english teacher who is just there to get some part-time cash-in-hand (usually 10,000 JPY). Do not ever judge a religion or philosophy by the people that are supposedly following it, as you will be wrong in 100% of cases. KägeTorä - (影虎) (TALK) 03:23, 23 September 2011 (UTC)

- This seems to contradict what you're saying, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shinto#Kokugaku ScienceApe (talk) 05:12, 23 September 2011 (UTC)

- Shintoism is not Buddhism, which has no official god nor gods, in the same way that Christianity is not Judaism nor Islam. Willminator (talk) 17:49, 23 September 2011 (UTC)

- I didn't say they were the same. ScienceApe (talk) 18:43, 23 September 2011 (UTC)

- Although see Religion in Japan. I quote: "Shinto and Japanese Buddhism are therefore best understood not as two completely separate and competing faiths, but rather as a single, rather complex religious system." The Japanese apparently have a phrase; ""shin-butsu konko" meaning "Shinto-Buddhism jumble"[1]. Alansplodge (talk) 01:12, 24 September 2011 (UTC)

- I didn't say they were the same. ScienceApe (talk) 18:43, 23 September 2011 (UTC)

- Shintoism is not Buddhism, which has no official god nor gods, in the same way that Christianity is not Judaism nor Islam. Willminator (talk) 17:49, 23 September 2011 (UTC)

- This seems to contradict what you're saying, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shinto#Kokugaku ScienceApe (talk) 05:12, 23 September 2011 (UTC)

- OK, Buddhism and Shinto are not related in any way whatsoever. Going by what the simple people do is not a way to understand any religion. The Japanese will go to the buddhist temples to 'revere their ancestors', and go to a Shinto shrine to celebrate a new house being built. The same people will go to a fake chapel to have a 'wedding' done by an english teacher who is just there to get some part-time cash-in-hand (usually 10,000 JPY). Do not ever judge a religion or philosophy by the people that are supposedly following it, as you will be wrong in 100% of cases. KägeTorä - (影虎) (TALK) 03:23, 23 September 2011 (UTC)

- People are missing the role of feudal religion in feudalism. The normal attack I observe when atheists attack Tibetan buddhism for its horrific feudal rule, is an attack on the hypocrisy of an elite feudal class claiming unattached non-harm doing as a release from the sufferings brought on by extreme desire whose economic base is attachment to vast land holdings that generate massive human suffering and harm. Marxist attacks have tended to focus on either or both of feudalism having been outdated in the area, in comparison to comprador post-feudal aristocracies in surrounding areas, or the Chinese bourgeoisie running-dogs; and, the fact that Tibetan feudalism was particularly horrific, and a failure in terms of maintaining calorific intakes and childhood survival rates (good markers of the real conditions of peasants in feudalism). The first attack is limited in that it is based on the idea that economics ought to be moral, and moralities ought to be consistent. The second is limited in that it posits a normative expected state of human existence based on a predictive theory of history. Fifelfoo (talk) 12:55, 26 September 2011 (UTC)

In this article it says Opposing him were the three Carthaginian generals (Hasdrubal Barca, Mago and Hasdrubal Gisco), who were on bad terms with each other, geographically scattered (Hasdrubal Barca in central Spain, Mago near Gibraltar and Hasdrubal near the mouth of the Tagus river), and at least 10 days away from New Carthage. However in Livy 26.44 it reads: When Mago, the Carthaginian commander, saw that an attack was being prepared both by land and sea, he made the following disposition of his forces. From Livy's description it sounds to me as if Mago is in the city of New Carthage defending it - not some 10 miles away! Am I misinterpreting one description or the other? Was Mago Barca at New Carthage or 10 miles away near Gibraltar?--Doug Coldwell talk 19:36, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

In Livy 26.46 it goes on to say: From this point Scipio saw the enemy retreating in two directions; one body was making for a hill to the east of the city, which was being held by a detachment of 500 men; the others were going to the citadel where Mago, together with the men who had been driven from the walls, had taken refuge.--Doug Coldwell talk 20:01, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- The article cites a book as its source, but doesn't quote from it. I can't tell if the material is correct or misquoted. It could be that the information is not necessarily incorrect. Mago could have returned to New Carthage with news of the attack. A horse traveling at 10 miles per hour would have gotten him there in an hour. It is possible to see advancing ships from a number of miles off from a lookout tower. I'm not sure if other sources exist, I am only aware of Livy. The historian may be dealing with concrete facts or some embellishments. Gx872op (talk) 20:20, 23 September 2011 (UTC)

- I could manage 8 or 9 miles in an hour on foot. A good runner could do 10 easily. Alansplodge (talk) 01:57, 24 September 2011 (UTC)

- The article says 10 days, not 10 miles. I don't know what's going on in this story, though. Adam Bishop (talk) 07:36, 24 September 2011 (UTC)

- Thanks Adam for noticing it is 10 days away. Polybius says in Book 10.7.4&5 concerning Scipio Africanus's arrival to Spain: For on his arrival in Spain he set everyone on the alert and inquired from everyone about the circumstances of the enemy, and thus learnt that the Carthaginian forces were divided into three bodies. Mago, he heard, was posted on this side of the pillars of Hercules in the country of the people called Conii; Hasdrubal, son of Gesco, was in Lusitania near the mouth of the Tagus; and the other Hasdrubal was besieging a city in the territory of the Carpetani: none of them being within less than ten days' march from New Carthage. However Polybius later says in Book 10.12.2 when Scipio circled New Carthage: Mago, who was in command of the place, divided his regiment of a thousand men into two, leaving half of them on the citadel and stationing the others on the eastern hill. How did Mago make it back to New Carthage if Scipio had it surrounded?--Doug Coldwell talk 12:00, 24 September 2011 (UTC)

- Reading Livy and Polybius, it seems that neither Scipio nor Mago were near Cartagena when Scipio decided to attack it, so maybe Mago had enough time to get there before Scipio did. Adam Bishop (talk) 15:15, 24 September 2011 (UTC)

- Good thought Adam, however this appears not to be true according to Livy 26.42 No one knew of his intended march (on New Carthage) except C. Laelius, who was sent round with his fleet and instructed to regulate the pace of his vessels so that he might enter the harbour at the same time that the army showed itself. Seven days after leaving the Ebro, the land and sea forces reached New Carthage simultaneously. A few lines before this Livy talks of the 3 Carthaginian generals being in 3 different parts of Spain - some 10 days away from New Carthage. It was a secret mission that the 3 Carthaginian generals knew nothing about.--Doug Coldwell talk 19:34, 24 September 2011 (UTC)

- Reading Livy and Polybius, it seems that neither Scipio nor Mago were near Cartagena when Scipio decided to attack it, so maybe Mago had enough time to get there before Scipio did. Adam Bishop (talk) 15:15, 24 September 2011 (UTC)

- Thanks Adam for noticing it is 10 days away. Polybius says in Book 10.7.4&5 concerning Scipio Africanus's arrival to Spain: For on his arrival in Spain he set everyone on the alert and inquired from everyone about the circumstances of the enemy, and thus learnt that the Carthaginian forces were divided into three bodies. Mago, he heard, was posted on this side of the pillars of Hercules in the country of the people called Conii; Hasdrubal, son of Gesco, was in Lusitania near the mouth of the Tagus; and the other Hasdrubal was besieging a city in the territory of the Carpetani: none of them being within less than ten days' march from New Carthage. However Polybius later says in Book 10.12.2 when Scipio circled New Carthage: Mago, who was in command of the place, divided his regiment of a thousand men into two, leaving half of them on the citadel and stationing the others on the eastern hill. How did Mago make it back to New Carthage if Scipio had it surrounded?--Doug Coldwell talk 12:00, 24 September 2011 (UTC)

Ancient Egyptian religions[edit]

The religion of the pharaohs seemed to offer very little to the common people. At best, they could hope to be killed when the pharaoh died and be entombed with him to continue to serve him in the afterlife. Was this the reason for the formation of the Sun-worshiping religion ? Was it more egalitarian in the afterlife ? StuRat (talk) 21:53, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

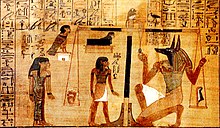

- Actually that's the hollywood perception of the Ancient Egyptian religion. Originally only pharaohs had access to immortality, sure, but it slowly grew to include commoners as well. By the New Kingdom, Ancient Egyptian religion was already quite egalitarian. Very similar to Greek religions. Everyone were mummified after death though understandably with less fanfare than pharaohs. The ruler of the afterworld was also not the pharaohs nor the sun god, but Osiris. The father of the purported father of the original pharaoh, and the god of rebirth.

- Everyone, even pharaohs had to pass the Weighing of the Heart by Anubis. Having their heart weighed in a balance against the feather of truth and justice (a manifestation of the goddess Maat). If they don't pass, their souls get eaten by the demoness Ammit. If they pass, they go on to the afterlife and go boating with Osiris happily ever after LOL, provided that they remember their names and had their body preserved. See Book of the Dead, for a description of the journey of the souls (Egyptians believed in two souls - an earthly one Ba and a heavenly one Ka, all tied to your body and your name).

- The very brief monotheistic period in Ancient Egypt was not the result of people converting willingly either. It was forced upon them by Akhenaten who also tried to erase the old religions in the process, completely replacing it with the worship of only one god - the Aten (sun disk), very reminiscent of later Abrahamic religions. Note that while there was already a sun god in Egyptian religions - Ra, he was not equivalent to the sun disk, though Akhenaten originally claimed it so. The Aten was merely the sun itself. It's now known as Atenism and it was quite unpopular

- In fact, after his death, his son Tutankhaten was immediately pressured by priests to revert to the old religions. He also changed his name in the process, changing allegiance from Aten to the god of the most powerful cult before his father took charge - that of Amun. He became the boy pharaoh we now famously know as Tutankhamun. All traces of Akhenaten and the worship of Aten was subsequently deliberately erased when Tutankhamun died and was replaced by Horemheb. -- Obsidi♠n Soul 23:06, 22 September 2011 (UTC)

- One of the major questions about Egyptian religion is what ordinary people thought about it and how much their beliefs and practices fit in with the "official" religion, which was overseen by the pharaoh and run by the priests. Modern understanding of those issues is severely hampered by the lack of written evidence (the vast majority of Egyptians were illiterate and didn't write down what they were doing or believing). Even so, most Egyptians seem to have believed that the gods were involved in their daily lives and could be called upon for help. And even though official rituals were closed to the general populace, that populace does seem to have regarded temples as particularly holy places, where they could contact the gods indirectly. See Ancient Egyptian religion#Popular religion and Egyptian temple#Popular worship.

- In the afterlife, the Egyptians had all the beliefs Obsidian Soul points out, and more. Atenism, in contrast, doesn't seem to have said anything substantial about the afterlife. Many Egyptologists have said that Atenism's lack of detailed mythology or afterlife beliefs—the colorful elements that made traditional Egyptian religion accessible to ordinary people—was a major factor in its rejection by ordinary Egyptians. If anything, it was more pharaoh-centric than the traditional religion: Atenist writings are mostly about the Aten and its relationship with Akhenaten. Some Egyptologists (e.g. Jan Assmann, Jacobus van Dijk) argue that Akhenaten was attempting to reassert the religious importance of the pharaoh in the face of a growing trend toward direct, personal worship of the gods. A. Parrot (talk) 20:41, 23 September 2011 (UTC)