Wikipedia:Reference desk/Archives/Science/2021 January 24

| Science desk | ||

|---|---|---|

| < January 23 | << Dec | January | Feb >> | January 25 > |

| Welcome to the Wikipedia Science Reference Desk Archives |

|---|

| The page you are currently viewing is a transcluded archive page. While you can leave answers for any questions shown below, please ask new questions on one of the current reference desk pages. |

January 24[edit]

If Stephen Hawking alive, would he win Nobel Prize 2020 along with Roger Penrose?[edit]

If Stephen Hawking alive, would he win Nobel Prize 2020 along with Roger Penrose? Rizosome (talk) 14:28, 24 January 2021 (UTC)

- We don't do crystal-ball work here. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 16:22, 24 January 2021 (UTC)

In Penrose–Hawking singularity theorems it clearly mentioned Penrose won Nobele prize. So what about Stephen Hawking? It just a doubt on Nobel Prize 2020. Rizosome (talk) 16:40, 24 January 2021 (UTC)

- Have you asked the Nobel Prize committee? ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 17:04, 24 January 2021 (UTC)

- How so is this a doubt on the Nobel Prize. Should the Committee have withheld the prize from Penrose because Hawking is dead? If Penrose were to blame for his death, that would have been reasonable, but as far as we know, he is blameless in this respect. --Lambiam 17:25, 24 January 2021 (UTC)

- I don't know about the OP, but my work colleagues from India use the term "doubt" to mean simply that they have a question about something they don't fully understand. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 17:52, 24 January 2021 (UTC)

- Note that the 2020 Nobel prize in physics was won jointly by three people, which is the maximum that a prize can be shared amongst. So if Hawking had been alive, one of Andrea Ghez and Reinhard Genzel would have had to be dropped if Hawking was going to be included, which would have been a difficult choice. Penrose won ""for the discovery that black hole formation is a robust prediction of the general theory of relativity", not specifically for the singularity theorem. Mike Turnbull (talk) 17:55, 24 January 2021 (UTC)

- According to Sixty Symbols, it was in particular his paper "Gravitational Collapse and Space-Time Singularities"[1] that was the great breakthrough he performed; it showed for the first time that singularities could arise from gravitational collapse, even if the collapse was without spherical symmetry. It became one of the most important papers in explaining black hole formation. --Jules (Mrjulesd) 18:08, 24 January 2021 (UTC)

- Note that the 2020 Nobel prize in physics was won jointly by three people, which is the maximum that a prize can be shared amongst. So if Hawking had been alive, one of Andrea Ghez and Reinhard Genzel would have had to be dropped if Hawking was going to be included, which would have been a difficult choice. Penrose won ""for the discovery that black hole formation is a robust prediction of the general theory of relativity", not specifically for the singularity theorem. Mike Turnbull (talk) 17:55, 24 January 2021 (UTC)

- I don't know about the OP, but my work colleagues from India use the term "doubt" to mean simply that they have a question about something they don't fully understand. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 17:52, 24 January 2021 (UTC)

References

- ^ Penrose, Roger (January 1965). "Gravitational Collapse and Space-Time Singularities". Physical Review Letters. 14 (3): 57–59. Bibcode:1965PhRvL..14...57P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.14.57.

Food preparing costs vs obtained energy[edit]

Could it be argued that some (or many) types of dishes require more energy for preparing than that obtained from their consumption (plus monetary costs of ingredients and time so that convenience food is more efficient)? 212.180.235.46 (talk) 22:57, 24 January 2021 (UTC)

- No, it doesn't, and one way you know this is that people who cook all or most of their food (not at all uncommon) don't quickly die from starvation and lack of energy. Just doing a back of the napkin calculation, I think this betrays a misunderstanding of the chemical energy density of most foodstuffs. Running a mile, for example, burns about 100 kcal of energy. A bowl of spaghetti with tomato sauce, on the other hand, has about 200 kcal in it. Generally, one would consider a mile run to be a lot more physical effort than that needed to prepare a bowl of spaghetti, and that spaghetti dish has about 2 miles worth of running in it. I've literally cooked this dish from scrap, meaning I even made the spaghetti pasta myself and didn't just use store bought dry pasta, and it's still a lot less effort than running a mile. This, by the way, is one of the reasons why exercise alone is often not enough for a weight loss regimen, but needs to be in concert with a healthy diet. It takes a LOT of physical activity to burn off the calories in our food. --OuroborosCobra (talk) 23:09, 24 January 2021 (UTC)

- I hope you made your meal from scratch rather than from scrap. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 23:16, 24 January 2021 (UTC)

- I think there are two edge cases to OuroborosCobra's reply, but they're for specific circumstances. One would be specialty or exotic foods, where there's some aspect of their collection that outweighs their calories. I'm thinking here of stuff that is foraged, like fiddleheads or mushroom hunting, where you might expend a lot of energy with little caloric return. Of course, the presence of nutrients could offset the cost/benefit disparity. The other edge case would be fresh water. Access to fresh water is a huge concern to millions around the globe and it returns no calories. If we're going to be completely pedantic, walking over to the tap and getting yourself a cup of water probably burns more calories than it provides, but we're talking about minuscule energy amounts anyway. However, there are people who need to walk many miles to get their daily water. Your final question is very different from your supposition, though. Deciding to get take-out versus home cooked involves a lot more inputs than just the calories expended in preparation. Matt Deres (talk) 15:39, 25 January 2021 (UTC)

- I read the question in a different way, thinking of the energy requirements of cooking food. If you use a litre of water to boil your spaghetti, and tap water is at 20 °C, you will use 80 kcal to boil the water, and more once you factor in energy inefficiencies associated with heat loss, etc. So in that sense preparing cooked food may often require more energy than obtained from its consumption. Jmchutchinson (talk) 17:07, 25 January 2021 (UTC)

- Once convenience food was brought in, I rejected that as a possible interpretation. A pizza required the heat of an oven to cook whether you made the pizza at home in your own oven or bought a slice at 7-11. The only advantage, energy wise, would be the work that the consumer put into it. --OuroborosCobra (talk) 19:03, 25 January 2021 (UTC)

- There's a lot of separate considerations here. If I am crushing a spice by hand in a mortar and pestle, or chopping onions by hand, I tend to stop as early as I can. If I have an electric spice mill or a food processor I will probably crush/chop it more finely. If I had to gather my firewood on foot, I will tend to cook my porridge groats using minimal heat, boiling at ambient pressure; if I am an industrial manufacturer of breakfast cereals, I will flash-cook them at hundreds of degrees, firing them from a high-pressure "gun", and I will finely pulverize the original grains, not leave groat-size lumps. See, the faster my production line runs, the more profit I make; energy consumption is secondary.

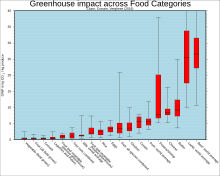

- As Jmchutchinson said, it is very common for people to use more energy producing food than they get out of it (carbon intensity of food), but the trick is that they don't use the energy of their muscles. They use external sources of energy, like firewood and watermills and oxen and plow horses and coal-fired steam turbines feeding an electrical power grid and boat fuel and tractor fuel and solar collector ovens. If you want to minimise the amount of energy used to prepare your food, then buy raw food and prepare it by hand (and avoid grain/pulse-fed animal products, heated-greenhouse produce, and the like). This also seems to be healthier than convenience food, possibly because we did not evolve to eat food finely pulverized at extreme temperatures and pressures (sugar, for instance, seems to be fine in intact plant cells, and unhealthy in juice, syrups, and other processed forms.[1]).

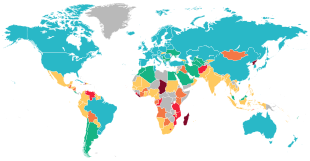

< 2,5%

< 5,0%

5,0–14,9%

15,0–24,9%

25,0–34,9%

> 35,0%

No data

- Possibly also because convenience food is often very cheaply-made, with very cheap, highly-standardized ingredients and processes. A surprising amount of convenience food is water, cheap oil extracted at very high temperatures and pressures, emulsifiers so the oil and water mix, and assorted thickeners (so it doesn't dribble). This is then tweaked with added colours and flavourings, and lots of sugar and salt. These ingredients tend to be highly-processed, and thus chemically predictable. Plus a minimal amount of things you might expect, like meat and produce. You may be able to work out the proportions from the nutritional information on the label. A preprepared sauce containing only 20% ingredients you'd put in a homemade sauce, plus 80% cheap goo (by weight), is not too unusual. Caveat emptor!

- Eating unhealthily increases the likelihood of spending time ill and dying young, which is a very inefficient use of time, so talk to your doctor about any dietary changes you are planning.

- In terms of time, certainly mass-produced dishes are more labour-efficient than small-scale hand-prepared dishes. Mass-produced foods are generally made with minimal labour, because labour costs money. Home-processing choices may also minimize labour. Eating things fresh, or lightly-steamed, rather than cooked to a pulp, is faster. Nixtamalization makes it easier to grind maize (corn). Slowcookers with boil-dry sensors reduce the labour of watching the pot. A slow cooker may well use more energy than a big industrial facility rapidly pressure-cooking food after it's been sealed into tins (but do you count the energy needed to make and recycle the tin?).

- There is a third efficency consideration: waste. The planet produces enough food to feed us all, but because wealth is very unevenly-distributed, so is food. One in four humans goes hungry or is malnourished.[2] Many rich nations waste half of their edible food. Buying something and then leaving it to rot is very inefficient. Buying food in small portions surrounded by masses of disposable packaging is also very inefficient; packaging costs energy and labour.

- I'm not sure how you would count money and time on the same scale, you have to make that choice yourself (possibly depending on what you are paid, and how much you enjoy your paid work and cooking).

- Of course, there are foods that do not require large amount of energy or prep time. If you have an apple tree growing outside your door, and you pick an apple and eat it fresh, that was very efficient indeed. Ditto greens, nuts, tubers. If this is what you want, I recommend reading up on hunter-gatherer food technologies. Hunter-gatherers generally get a more varied diet for less work (maybe about a quarter less), compared to contemporary agriculturalists. Despite the rather colonialist name, "hunter-gatherer"s carefully engineer the landscape around them to yield food with minimal effort. For instance, in Australia, landscapes were maintained to ensure good habitat for kangaroos -- and to ensure they could be easily caught at harvest-time. Areas of land can be cared for and weeded to make them more suited to important food plants, such as the camas meadows of North America. On coasts and rivers around the world, huge, elaborate structures and systems improved fish habitat and made the fish easy to catch. These landscapes need human maintenance, but they are very labour-efficient and low-input. They often aren't easily mechanized using early industrial technology, but with the advent of cheap sensors and data processing, this may be changing.

- Of course, hunter-gatherers and agriculturalists alike optimize for their circumstances, which historically did not include electrified kitchens, drones, fast-food takeaway, combine harvesters, or frozen pizza. You will also optimize for your preferences and resources (you can't plant an apple tree by your door if you live in a skyscraper). "What will I eat?" is a fascinating question which determines a lot about our societies. HLHJ (talk) 04:29, 27 January 2021 (UTC)

- That's a serious answer there HLHJ. To add a bit to your hunter-gatherer point, sort of related to the OP's energy balance concern: Over the past few years, thousands have tried surviving off the wilderness & uploaded to the youtube. Many weigh themselves before & after, to see if their successful in ingesting more calories than the effort gain it (plus the metabolic burning during their survival stint.). Generally, they find they burn more calories than they've been able to eat - even when it's only say a 5 day challenge, in the fruiting season, in land they know is good for fishing & trapping, and when they have good craft & tools. It can make the difference if they cheat a little, taking a few convenient packs of pasta for some quality carbs. FeydHuxtable (talk) 12:52, 29 January 2021 (UTC)

- Thanks, FeydHuxtable, I had no idea! That sounds a bit like the people with no farming background who abruptly try farming, and work very hard but usually fail financially. Though I guess to make the analogy complete they'd also have to start with no farm, which they usually don't. Engineering a landscape to support you is not a trivial skill. Since hunter-gatherer groups pushed off traditional lands onto some superficially similar lands have struggled to adapt, then starting abruptly from a non-hunter-gatherer culture, in an untended landscape, seems like it should be a lot harder. I'm sure this list is very incomplete, but people living primarily by hunting and gathering

- have an utterly encyclopedic knowledge of their lands, with every food source and its attributes (so they will know from their memories of the weather which potential food sources will be abundant and worth going to this year, and tag a short rant about climate into any such discussion).

- tend to have varied and far-flung food sources, often with use rights that traditionally interlock and overlap with those of others (to a degree depending on the climate)

- have highly-optimized skills, techniques and tools, specific to the landscape

- often trade some of their opson or labour to adjacent agriculturalists in exchange for some sitos, like convenient packs of pasta.

- But that last is evidently not an obligatory condition. Skilled hunter-gathers who avoid external foods for medical or conviction-based reasons manage fine. And indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation seem to make a living, too. Statistics on the food economy of modern hunter-gathers are also skewed from historical and pre-historical practice by the fact that agriculturalists have selectively occupied a lot of land. For an extreme example, few hunter-gatherer populations we know very much about were more isolated from bulk overseas trade in foodstuffs than pre-European Australia as a whole. It would thus be hard to argue that Australian Aborigines were dependent on agriculturalists before European settlement -- unless you count some Aboriginal activities as agriculture. Now, you easily could, but the European settlers didn't; they argued that if you weren't settled in the same place all year round then the land did not belong to you, even if you dug it over every few years or built permanent houses and granaries on it.

- Conversely, agriculturalists usually do a bit of hunting and gathering on the side. The original post is from Europe, where agriculturalists fish, hunt animals like rabbits and edible dormice, gather wild mushrooms like boletus and shaggy ink cap, wild berries like sea-buckthorn, bilberries, and cloudberries, wild nuts like filberts and chestnuts, and wild greens like fiddleheads and corn salad and plantago. And they traditionally maintained fish ponds and deer parks and coneygars and pigeon lofts, planted coppices with food plants, bought free warrens and so on. Plus they usually buy food!

- So while building and following food sources across large swaths of European countryside won't work for social reasons, and attempting to live entirely off a patch of untended land won't work for practical reasons, shifting part of your diet gradually, as you learn the skills, can work. And there will be people to teach you. Something like planting a bit of corn salad in balcony pots or a garden would be likely to work in most of Europe, if you took a bit of advice (community gardens often teach such skills). It would also be cheaper and quite possibly even lower-effort, over time, than buying herbs and salad. Perennials and self-seeding plants reduce the effort. A fair number of people manage to get all their produce from a hundred-odd square meters of food garden, either a house garden or separate allotments, though growing grain on such small plots tends to be a bit useless (the yield is tiny). But this takes skill and knowledge and practice, and suitable cultivars and attention to the soil and effort and elapsed time. Decent exposure helps too. And it's not lower-effort than ordering food from a grocery store, but it is likely to be more energy-efficient. Sorry, that was mostly rather irrelevant to your reply. Interesting topic. HLHJ (talk) 05:22, 30 January 2021 (UTC)

- Thanks, FeydHuxtable, I had no idea! That sounds a bit like the people with no farming background who abruptly try farming, and work very hard but usually fail financially. Though I guess to make the analogy complete they'd also have to start with no farm, which they usually don't. Engineering a landscape to support you is not a trivial skill. Since hunter-gatherer groups pushed off traditional lands onto some superficially similar lands have struggled to adapt, then starting abruptly from a non-hunter-gatherer culture, in an untended landscape, seems like it should be a lot harder. I'm sure this list is very incomplete, but people living primarily by hunting and gathering

- That's a serious answer there HLHJ. To add a bit to your hunter-gatherer point, sort of related to the OP's energy balance concern: Over the past few years, thousands have tried surviving off the wilderness & uploaded to the youtube. Many weigh themselves before & after, to see if their successful in ingesting more calories than the effort gain it (plus the metabolic burning during their survival stint.). Generally, they find they burn more calories than they've been able to eat - even when it's only say a 5 day challenge, in the fruiting season, in land they know is good for fishing & trapping, and when they have good craft & tools. It can make the difference if they cheat a little, taking a few convenient packs of pasta for some quality carbs. FeydHuxtable (talk) 12:52, 29 January 2021 (UTC)

- Of course, hunter-gatherers and agriculturalists alike optimize for their circumstances, which historically did not include electrified kitchens, drones, fast-food takeaway, combine harvesters, or frozen pizza. You will also optimize for your preferences and resources (you can't plant an apple tree by your door if you live in a skyscraper). "What will I eat?" is a fascinating question which determines a lot about our societies. HLHJ (talk) 04:29, 27 January 2021 (UTC)

References

- ^ "Reducing free sugars intake in children and adults". WHO.

- ^ "The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020 | FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations". www.fao.org. FAO. Retrieved 27 January 2021.