1583 Assembly of Notables

The 1583 Assembly of Notables (French: Assemblée des notables de 1583) was a gathering of much of the political elite of the kingdom of France in addition to financial and technical experts in administration. The meeting hoped to reform France's shaky financial situation. Efforts towards the financial reform of the kingdom had been a feature of the reign of king Henri III since the Estates General of 1576. The crown was in a great amount of debt, and the royal taxes were increasingly insufferable to the French people. In the Grand Ordonnance de Blois issued in 1579, which summarised many of the requests of the Estates General, a large number of financial reforms were put forward. However, Henri was forced to turn to various expedients due to the financial demands of first the civil wars, then his brother the duc d'Alençon's military exploits in Nederland and then the needs to pay off the foreign mercenaries to whom the crown was indebted. By 1582 Henri, faced with increasing resistance to the crowns financial policy from the provinces, was resolved to break the pattern of expedients.

In August 1582 he established commissioners who were to go out into the provinces and find out the grieviances of the royal officers and the representative assemblies of the kingdom. Where they identified officials to be guilty of abuses they were also to apply sanctions. Having toured the kingdom, the various groups of commissioners were summoned to arrive back in Paris for September 1583. The conclusions of their tour were to be summarised for council and then form the basis for an Assembly of Notables. The Assembly of Notables opened in November 1583 and contained 66 participants, largely embodying administrative experts and functionaries, but also many of the great nobles of the kingdom such as the cardinal de Bourbon. Opening the Assembly on 18 November, Henri presented to the notables a radical tax plan, first presented to the Estates General of 1576 by which several existing taxes would be abolished and replaced with a single income/wealth tax structued over 30 bands. This was unpalatable to the assembled notables who proposed instead that Henri work towards the redemption of the royal domain (much of which had been alienated into private hands to raise short term funds) rather than raising new taxes. The cardinal de Bourbon implored Henri to re-establish unity of religion in the kingdom, but Henri dismissed his pleas. After two months of deliberation, the Assembly presented to Henri in February a host of proposals, among which were a reduction in the size of the army, a reviewal of the contracts made with the tax farmers and those to whom he had alienated elements of the royal domain a revitalisation of French manufacturing and a suppression of abuses in tax collection. Over the following year, Henri's edicts would embody many financial policies championed by the Assembly, including a reform of the military, the reissuing and consolidation of several tax farms at a more favourable rate, the establishment of a court to punish financial abuses and the suppression of the unpopular taille (land tax) in areas it had been recently introduced into. In 1585 Henri enjoyed the fruits of these efforts in a radically reduced royal deficit. However the reforms were not able to entrench further as France fell into a politico-religious crisis as represented by the uprising of the Catholic ligue (league).

Financial crisis

[edit]Debt and mismanagement

[edit]

During the latter 1570s the kingdoms financial situation was precarious. In 1576, for example, the royal revenues totalled around 14,000,000 livres, while the state debt equalled 101,000,000 livres. In light of this situation, king Henri III abandoned the notion of sweeping away venal office (state offices that you paid to acquire) expanded the alienation of the royal domain (selling off crown lands to private individuals) and undertook a program of taxing the towns while also subjecting them to forced loans. In an effort to control inflation in 1577, it was proposed that the écu (crown) be re-valued as being equivalent to three livres (pounds). In the edict of Poitiers the accounting system of the kingdom was tied to the écu au soleil as opposed to a fictional accounting unit.[1] While this controlled inflation to a certain degree, over time the accounting unit of the écu began to diverge from the physical currency.[2]

The provinces baulked at the fiscal demands of the crown in 1578–1579, with the provincial Estates of Bourgogne, Bretagne and Normandie refusing to yield despite the sending of royal commissioners. To this end they cited their privileges.[3] Real reform was demanded.[4] In 1579 Henri issued the Grand Ordonnance de Blois which was composed of 363 articles and aimed at addressing grievances raised in the Estates General of 1576.[5] This ordonnance declared a reduction in the membership of the sovereign courts and présidieux courts, prohibited the venality of office and legislated on the alienation of the royal domain.[6] It also weighed in on the kings household, the functioning of the army, access to ecclesiastical office and the various responsibilities of members of the royal courts.[7] While the peace's of Bergerac in 1577 and Fleix in 1580 relieved some of the financial pressures on the crown this was not to last. During 1580 Henri tasked four financial specialists (Antoine de Nicolay, the seigneur de Chenailles, Pierre de Fit and Nicolas du Gué) with studying the practicality of the redemption of the royal domain.[8] This commission informed him of the overall value of the royal domain (alienated or not), which was put at around 50,000,000 livres.[9] The exploration of the possibility of repurchases was not able to progress significantly before Henri was obliged to alienate more of the royal domain.[10]

From 1581 Henri was burdened with a new expenditure, the financial support of his brother (the duc d'Alençon's) military exploits in Nederland. The alternative to backing this endeavour would be to face another revolt from Alençon in France. Thus peace with the Protestants alone would not be sufficient to restore the kingdom to financial stability.[9] In November 1581 he declared the expansion of retrait lignager (rules of property alienation as regards inheritance) would be in force throughout the kingdom of France, including those areas in the south of the kingdom which operated on written law as opposed to customary law.[11] In July 1582 Henri renewed the French alliance with some of the Swiss cantons and made a treaty with them at Solothurn concerning the arrears of their pay as mercenaries that cost the crown 600,000 écus.[12] These expenses forced him to once more turn to expedients and he alienated more of the royal domain, created more venal offices, took out 6 new loans and instituted further taxes on the clergy, cloth and wine.[13] In Picardie and Champagne there were riots against paying the new aide (excise tax) on cloth and wine during the summer of 1582.[14] With these disorders threatening to spread into the south, Henri turned to his brother in October to aid with matters. Chevallier argues that fortunately for Henri, the duc d'Alençon refused.[12] On 2 August, it was admitted in conseil that the royal budget deficit equalled around 200,000 écus.[13]

Breaking bad habits

[edit]By 1582, Henri was looking for a way out of the cycle of financial expedients required to keep the balance sheet afloat. According to the English ambassador he kept scribes nearby him at all times to record his ideas for fiscal remedies.[15] The first step in this direction was taken on 27 May 1582 when the conseil des finances (finance council) received orders to meet from 13:00 every day for two hours to explore methods by which the king could be restored to his domains and other incomes, such that he could live off his own lands and spare the people their troubles. During a meeting of the conseil d'État on 16 July, Henri announced his intention that an investigation would be undertaken towards the duel purpose of the domain's redemption and the relief of the peoples sufferings. The realm was divided into six sections, each of which would be the responsibility of a group of four commissioners. The commissions were sent out to the commissioners from 3 to 6 August.[16][12] Each area was to be overseen by a commission of four and was led by a prelate, and contained a member of the conseil privé (privy council) who had experience of war, a magistrate and an expert in finance.[14] The historian Karcher notes that the second figure of the group was a 'noble of average importance who had offered years of service to Henri either as a soldier or a diplomat'.[17] The Lyonnais, Dauphiné and Provence were entrusted to the bishop of Nantes, the seigneur d'Abain, Jacques Baillet an advisor to the grand conseil and Charles Le Comte one of the maître des comptes (master of accounts).[18] Languedoc and Guyenne were the responsibility of the archbishop of Vienne, the sieur de Maintenon, Jean Forget a conseiller in the Paris Parlement and Denis Barthélemey one of the maìtre des comptes. For Normandie and Bretagne were given the archbishop of Lyon, the the seigneur de La Mothe-Fénelon, the seigneur de Blancmesnil one of the maître des requêtes and Pierre de Fitte de Soucy a former trésorier de l'Épargne. The final group whose membership is known is that responsible for the Île de France, Picardie and Champagne which was composed of the bishop of Châlons, the comte de Marennes, Jacques de Bauquemare one of the maître des requêtes and a man named Beaurains who Karcher imagines to be a financier.[17] These commissions departed from the court during October. Ahead of them travelled notices from the king to the provinces, ordering the officials and bodies to be ready to answer the commissions questions.[12] These commissions visited all the provinces of the kingdom.[19]

Alongside this, in early 1583, Henri looked to bring about the alienation of 100,000 écus (crowns) of the churches property. This was greeted with strong resistance form the clergy in a Paris assembly on 28 March. Henri also ran into opposition on the conseil privé. He dispatched his sécretaire (secretary) Jules Gassot to negotiate on the matter with the Pope in Roma. Through the Papal Nunzio (the Pope's ambassador and representative), the Pope warned Henri that if he persisted in his designs against church property the sacrament would be refused to him. Stung, Henri was forced to retreat from the project.[20] On 19 March, Henri declared the prohibition of the importation of foreign luxury goods into the kingdom. That same month a new regulation of the taille was instituted by the king.[12]

Commissions to the provinces

[edit]Arriving in a province, the commission would liaise with the governor and his lieutenants to be assured of their backing during the stay. The commissioners would then enquire as to the religious, political and economic situation in the province.[17] They were to make it clear to the notables that Henri intended for the edicts of pacification to be abided by so that his subjects might live in peace.[21] The commissioners carried sealed letters from the king explaining the specific troubles of the province they were in.[22] They would then tour the cities of the province and convene representative assemblies. It would not just be in the cities that they conducted their enquiries but also through stopping regularly in their travels to speak with tax collectors and churchwardens. The local Estates would also be consulted, and all financial officials, be they of the state or of the church quizzed. It was to be explained to the provincial Estates Henri did not desire to increase taxation but rather to cure the issues that might cause the collapse of the kingdom. If the commissioners were subject to demands for an Estates General they were to ignore them.[22] By this means it was hoped all facets of public life that required the crowns attention could be seen, and further any grievances as to the present state of things aired.[19]

In such instances as they identified royal officials, nobles or clerics to be guilty of abuses (be it their abuse of power, disobedience or embezzlement) the commissioners were authorised to apply sanctions on the official.[19]

The commissioners received a cool greeting from the local authorities with which they met. Despite this they applied serious effort to the task at hand, spending six months in the pursuit of their missions. They left a heavy mark in the local archives of the places they visited.[19]

It is challenging, due to the paucity of surviving documents to follow the courses of the commissions. It is known however that the commission that arrived in the Lyonnais oversaw a reform of justice.[23]

Karcher describes these commissions as a particularly original innovation of Henri due to the tripartite mission they were undertaking. The combination of a national consultation, administrative reform and investigation was a novelty.[23]

In May and June 1583, committees were formed to investigate the possibility of reducing the number of judicial officials and reforming the hospitals of the kingdom.[24] The investigation into reform of the hospitals was led by the parlementaire La Guesle and the grand aumônier (great chaplain) Jacques Amyot.[25]

Preparation for an Assembly of Notables

[edit]

On 30 June 1583, Henri summoned the commissioners to return to the capital, aiming to rendezvous in Paris on 10 September. This was to have them arrive 5 days before the intended start date of the Assembly of Notables, which he looked to begin on 15 September. However the plague was carving a path through Paris, so this was reconsidered.[26] At the same time as he called back the commissioners he sent a summons to the various princes du sang (princes of the blood) and 'several other lords' so that they might hear the results of the commissioners work and make suggestions as to how to resolve the problems raised.[27]

Henri arrived at the royal residence of the château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye with the court on 9 October, having been at Bourbon-Lancy.[28][27] It would be here that the Assembly met.[26]

Upon the return of the commissioners to court in October 1583 they received the order on 4 November to prepare a unified general report upon which they were to meet together every day until it was ready.[27] A 48 chapter report would presented to the royal conseil. This was supplemented by a memorandum on each province, where general grievances and specific matters were outlined. Only those of Bretagne and Normandie survive in the record. The documents outline the poor state of royal finances, and the frustration of the French people at the burden of the direct and indirect taxations they were subject to.[4] The commissioners noted the demoralised nature of the clergy who required an external renewal to undertake an internal one. The plague of militant bands that terrorised the kingdom was also noted with disapproval. Finally it was opined that little corruption among the kings officials had been observed, but that the judiciary was subject to intimidation.[22]

By the Autumn of 1583, Henri's sécretaire d'État (secretary of state) the seigneur de Villeroy was growing concerned that France was faced with an increasingly urgent crisis of both internal and external dangers. In particular the threat of invasion by the mercenary army of Pfalz-Simmern for his unpaid debts.[29]

Meeting of the Assembly

[edit]Choice of body

[edit]An Assembly of Notables would be convened to analyse the results of the investigations that had been undertaken and act as consultants for the remedies to be taken.[16][6] This was a more savoury alternative to the prospect of convening a new Estates General for the king.[30] The composition would thus be quite different from an Estates General, with few ecclesiastic representatives, no representatives from the cities, and the most senior parlementaires absent.[31] Karcher characterises it rather as an 'Assembly of officials'.[32] Henri hoped that the notables would be able to facilitate a reorganisation of the French tax regimen.[33] In addition to this the grand promises of the Grand Ordonnance de Blois could at last be realised, and the internal problems of the kingdom resolved so that France could reorientate towards an international focus for competition with España.[34]

This was Henri's second convening of an 'Assembly of Notables' his first turn to the institution having been in 1575.[7]

The announcement of the Assembly of Notables was a cause of both concern and relief for the ecclesiastical bodies. On the one hand it raised the spectre of a new attempt at alienations of church domains. However, on the other, it would so overwhelm Henri with various matters that it might protect the church from being made the source of the king's financial relief. There would be a number of senior prelates among the attendees also.[35]

The first draft of the program for the assembly was drawn up on 9 October, the day Henri arrived at Saint-Germain-en-Laye.[27] It was intended that the Assembly first be presented with the report drawn up by the commissioners, then a summary of the taxes that had been raised in 1583 alongside the royal expenditures. The abolition of various offices of finance would then be discussed. After this the 1580 report into the situation of the royal domain would be presented. The assembled notable would advise the king on the best means of securing redemption of the domain.[36] Justice would follow from this, facilitated by a report from the président La Guesle. The possibility of military reform would then be broached upon the advise of maréchal de Retz (marshal of Retz). The final subject of discussion would be the suppression of abuses in the Catholic church.[36] Through October and November the government worked towards a survey which the notables would be required to respond to and the projects upon which they would work.[37] Karcher argues that the thoroughness of the royal preparations, which had been put in the hands of specialists meant that the notables would in most cases do little to modify the projects that were put before them.[37]

Attendees

[edit]

In attendance would be 66 persons.[6] Each received a personal invitation from the king.[22] Those invited included the princes du sang (princes of the blood - agnatic blood relations of the royal family), the officiers de la couronne (officers of the crown), twenty six conseillers d'État (state councillors), the royal sécretaires, ten commanders of the royal compagnies d'ordonnance (ordinance companies), around half a dozen governors of various provinces, seven jurists, two diplomats and representatives of the two principal royal favourites: duc de Joyeuse, duc d'Épernon. Representatives of the queen mother Catherine and the king's brother the duc d'Alençon would also be in attendance.[16][19][38] All those who had served as commissioners in the provinces were among the attendees.[24] The historian Salmon characterises it largely as an assembly of 'technical experts'.[39] Protestant notables were notably absent.[40] While the sécretaire d'État Villeroy was not among the list of attendees, he would be present to support the king.[31]

The various Notables had begun gathering at the court from October. Karcher argues the Assembly did not begin at this time for several reasons. Firstly, Catherine was still undertaking her mission to secure the presence of Alençon. Secondly, around this time, representatives from the various provincial Estates of Languedoc, Provence, Guyenne, Bourgogne, and Bretagne had arrived at the court to protest tax increases. According to the English ambassador Henri wished to delay the start of the Assembly until their departure. Indeed on 5 November, these deputies who had gathered in a large room of Saint-Germain-en-Laye were removed from the room, and invited to instead present their concerns in writing to the king.[41] Nevertheless they would sit in on the early sessions of the Assembly.[24] Henri ensured they were absent from the important debates of the Assembly.[42] By 9 December, it is reported most of them had left, this was before the actual deliberations on the crowns proposals had begun and thus these representatives did not truly participate.[43]

Alençon and Catherine

[edit]Henri had hoped his brother Alençon would join him for the Assembly, and sent a request to this effect through the dispatch of his mother Catherine to La Fère to meet with the prince in August. Catherine informed her son that Henri was hoping that both he and the baron de Biron would be present for the upcoming Assembly of Notables, so that they might explain the situation in Nederland.[44] Catherine had no success in convincing him to attend, and would later report that 'malicious individuals' had convinced Alençon the Assembly would work to his disadvantage.[45] She scolded him for disobeying the king, and promised him money if he returned immediately to the French court. Around this time, Alençon had developed a high fever, and for the princes biographer Holt it is clear that this was the true reason for his absence.[46] Catherine did not put much stock in his illness.[47]

Representing Catherine during the proceedings would be one of her conseillers named Scipion de Fiesque. Meanwhile, the duc d'Alençon was represented by a noble of his household named the seigneur de Ponts.[26][46]

Princes du sang

[edit]For the princes du sang in attendance would be the cardinal de Bourbon, his nephew the cardinal de Vendôme and the marquis de Conti.[19]

Of the princes du sang, both the Protestant prince de Condé and Protestant king of Navarre would be absent. Neither wished to come to the assembly to deliver their remonstrances.[48] Navarre declined to attend on the grounds that it was not proper for a prince to deliver a petition.[22] The king of Navarre would however send the seigneur de Clervant to Henri, to provide the French king the Protestants' requests. The Catholic duc de Montpensier was also absent, Karcher speculates he may have been busy in Vlaanderen, or Dauphiné.[49]

Princes

[edit]For the princes of sovereign houses in attendance would be the duc de Guise, duc d'Aumale, duc de Mercœur and duc de Nevers.[19]

The duc de Mayenne and duc d'Elbeuf were both absent from the assembly. Karcher puts out the possibility they remained in the provinces so they could be a cause of disorder.[49]

Favourites

[edit]The chief royal favourites sent representatives to stand for their interests. The duc d'Épernon was represented by his elder brother the seigneur de La Valette, while the duc de Joyeuse was represented by his younger brother the comte de Bouchage.[48][30] Épernon was also present himself.[50] Joyeuse could not be in attendance as he was in Roma attempting to secure funds from the Pope.[49] The old royal favourite Villequier was in attendance.[43]

Military officers

[edit]For the maréchaux (marshals) would be the baron de Biron, the comte de Retz and seigneur d'Aumont.[19] This was three of the four maréchaux.[24] Among the other men with military offices would be the maréchal de camp Lenoncourt 'le jeune' one of the capitaines des gardes du roi (captains of the king's guard) the seigneur de Rambouillet and the capitaine de cent gentilhommes du roi (captain of 100 gentleman of the king) the seigneur de Chavigny.[51]

The maréchal de Matignon did not attend. He was occupied in the south of France working towards the appeasement of the Protestants.[49]

Governors

[edit]For the governors of cities or provinces would be the governor of Angoulême the marquis de Ruffec; the governor of Narbonne the baron de Rieux ; the governor of Lisieux the seigneur de Fumichon; the governor of Mézières La Vieuville and the former governor of Provence the comte de Suze.[51]

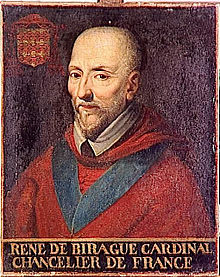

Officers of the crown

[edit]For the officers of the crown would be the chancelier (chancellor) Cheverny.[19] Cheverny occupied the position of garde des sceaux (holder of the royal seals - de facto chancelier) prior to his elevation to chancelier in November 1583 upon the death of the previous incumbent the cardinal de Birague.[52] Also present were the premier maître d'hôtel du roi Combault; the grand prévôt (great provost) the sieur de Richelieu; the grand maître des eaux et forêts (grand master of the waters and forests) baron de La Guerche; the grand aumônier Amyot; the premier écuyer du roi the seigneur de Sourdis; the lieutenant-civil Antoine Séguier; and the king's doctor Miron.[51]

For the royal financial offices would be the trésorier de l'Épargne the seigneur de Soucy; four maîtres des comptes (the seigneur de Miron, de Pleurs, Le Comte and Barthélemy) and two intendants des finances (the seigneur de Chenailles and the seigneur de Wideville).[51]

Men of the church

[edit]For the ecclesiastics: the bishop of Paris; the bishop of Châlons who had served in the commissions of 1582; the archbishop of Vienne who had served in the commissions of 1582; the bishop of Nantes who had served in the commissions of 1582; the archbishop of Lyon who had served in the commission of 1582.[51]

Men of the robe

[edit]For the royal courts, the former premier président of the Parlement of Rouen Bauquemare; the président Brisson; the président La Guesle; the président Faucon; the conseiller Forget; the avocat général a la cour d'aides du Gue and two maître des requêtes (the seigneur de Champigny, the seigneur de Blancmesnil).[51]

Other attendees

[edit]Among the other nobles would be the seigneur de Puyguillard; the seigneur de Maintenon who had served in the commissions of 1582; the seigneur d'Abain who had served in the commissions of 1582; the baron de Cessac; the comte de La Vauguyon; the seigneur de Piennes; the former French ambassador to España the baron de Saint-Gouard; the future ambassador to England the baron de Châteauneuf; the former ambassador to England the prieur de Champagne; the former ambassador to the Council of Trent the seigneur de Lanssac and the diplomat the comte de Nanteuil. [51]

There would also be a 'Monsieur Marcel'; in addition to Beaurains and Baillet who had served in the commissions of 1582[53]

Opening of the Assembly

[edit]

Having been delayed by the plague, Alençon and the delegates from the provincial Estates, the assembly would open on 18 November 1583.[54][34] The minutes of the notables' discussions do not survive.[40]

Henri delivered the opening address before the assembly. He opened by noting that they were, alongside some of the principal men of the kingdom, 'loyal advisors' and 'obligated servants'. He thus anticipated that they would consider no priority during their time at Saint-Germain aside from the betterment of the king, and France. To those who supported Henri in this mission he raised the prospect of the good grace he would afford them. Anticipating objections from the notables he highlighted the importance of preserving peace in the kingdom, as recent example had shown the dangers of civil wars.[32] He raised the unfortunate spectre that the ruin of the state might follow if their deliberations were not successful. He hoped that by their meeting they might see to the good of the state and the alleviation of the suffering of the people.[55] Henri reminded the assembled notables that god had granted him a power above all others, but that he could not achieve the ends he desired without their support. Peace alone would not suffice for the good of the state and people, better laws were needed. To achieve these ends the kingdoms financial position would need to be assured.[56]

To drive this point home to the Notables gathered at Saint-Germain, a document titled Estat du domaine et des finances de France (the state of the domain and the finances of France) was distributed, as well as a retrospective on royal finances since 1494.[33] The work began with a table which broke down the various elements of state property then moved on to a discussion of tax revenues from 1494 to 1581. Karcher highlights the accuracy of the figures presented to the notables in this document.[57] It is because of this she states that it would become such a reproduced work in the proceeding two centuries.[25] These documents had been drawn up by four maîtres des comptes (members of the chambre des comptes - chamber of accounts).[30] Further information was provided to the Assembly including a summary of the income enjoyed by the clergy, the bénéfices at the disposal of the crown, a summary of the royal debts, the commitments of the domain and the study into the hospitals that had been commissioned back in May.[25]

After Henri had spoken it was the turn of Cheverny, who spoke in lieu of the chancelier Birague as the latter was dying. Cheverny lauded the king for his desire to see the kingdom restored to its former health, and interest in the welfare of his people. Cheverny noted this was an example for the notables assembled to follow during the meeting.[40] The garde des sceaux urged the clergy to be ready to make sacrifices to support the king. In particular he accused the province of Normandie of being stubborn in this regard. The cardinal de Bourbon rose to object to this.[58]

Bourbon then turned and fell to his knees in front of the king begging Henri to restore uniform Catholicism in France. He stated to Henri that all the ills of the kingdom derived from the fact there were two faiths that were tolerated. He assured the king the clergy would give him their very last sou (penny) if he committed himself to the extirpation of Protestantism.[58] Henri was put out by this display from Bourbon and stated that he himself had fought against Protestantism, and that they were not converted by the sword.[58] He further added "Uncle, these speeches come not from yourself: I know from where they come; speak no more to me of it". That evening, the duc de Guise visited Henri to explain away the suspicion he was aware of that he had put the words in Bourbon's mouth. He protested the thought of doing so had not occurred to him, and if it had, he would have chosen a more able man to convey the words than Bourbon.[40] His interview with Henri was a cold one, and he failed to convince the king of his innocence.[59]

During the second day of the Assembly, 19 November, the intendant des finances Milon presented the various financial reports and discussed the states incomes and expenses.[59]

On 21 November, the bishop of Châlons presented the merged account of all the various commissions which had travelled across France, summarising the particular failings they observed.[59]

The président of the parlement La Guesle spoke on 22 November. He discussed the state of justice in the kingdom harshly, critiquing what he considered to be anachronistic privileges such as the practice of the archbishop of Rouen to release a criminal of his choice. This incensed the cardinal de Bourbon (who was also the archbishop of Rouen), who demanded La Guesle pay for his contempt. He further characterised La Guesle as being interested in his own self aggrandisement and charged the judiciary with corruption. La Guesle objected to this. Henri harshly ordered Bourbon to be quiet.[60][40]

Further speeches followed on 23 November from the sieur de Maintenon, the archbishop of Lyon and other figures.[61]

The grand prévôt Richelieu presented to the Assembly a report on the state of the court, in regards to its security, maintenance and the suppression of violence. Almost all he reported gained the approval of the notables.[62]

From 19 to 26 November members of the Lorraine-Guise family picked several quarrels. The brothers of the duc d'Aumale entered into dispute with the royal favourite the duc d'Épernon. Meanwhile the cardinal de Guise argued that he should have precedence over the cardinal de Vendôme on the grounds that he was a priest.[59] The clerical delegates at the Assembly rejected the Gallican idea to make it so that the Pope could not absolve a subject of their duties of obedience through the issuing of an excommunication.[24] The notion that the king and his officers could not be excommunicated was also rejected. In the opinion of the parlementaire de Thou, the rejection of this proposal reflected a growing current of ultramontanism.[63] These 'political incidents' however were the exception, and the Assembly was not dominated by them.[59]

From 26 November to 8 December président Fauchet and général Roland were brought in from the cour des monnaies (sovereign court in charge of the coinage) to provide further direction to the delegates on financial matters.[64]

The burial of the chancelier Birague (which transpired on 6 December) put a pause on proceedings for a while.[61]

Radical tax proposal

[edit]Henri proposed to those gathered that the taille (land tax) and the taxes on salt and wine all be replaced with a single tax that would be levied proportionate to the wealth of the household in 30 bands ranging from one sol up to 50 livres. He anticipated this would bring in between 25,000,000 and 35,000,000 livres. This plan had first been proposed by the crown during the Estates General of 1576, but had been rejected by the Third Estate then.[33]

After subjecting the proposal to their considerations and thinking on the matter, the notables shot down the king's proposal just as had the Estates. They proposed the king instead redeem parts of the royal domain. Through control of his domain there would be no need to raise taxes.[56] For the royal domain in the vicinity of Paris that had been alienated for 300,000 livres, Henri would, in the estimation of the notables, gain an income of 60,000 livres annually by its redemption, allowing him to pay off the price of the purchase within 6 years.[38] As concerned financial injustices they proposed a special tribunal of parlementaires who would hear cases of corruption and fraud. Henri therefore lost another opportunity to rationalise the French tax system, but succeeded in spreading awareness of the financial problems of the kingdom.[33]

It was also hoped that the notables would develop an implementation of the articles that had been promulgated by the king in the 1579 Grand Ordonnance.[65]

Division into chambers

[edit]Having returned to Saint-Germain on 12 December, the Assembly began to deliberate on the articles concerned with justice on 14 December.[61] Henri resolved to ensure that things kept moving in the Assembly that the body would be divided into three chambers, these chambers were not however those of the 'three orders' but rather a cross section of nobles, clerics and officials.[4][24] This offered the additional benefit of providing clearer conclusions to the king as there would now be three opinions presented to him, rather than individual opinions as had been the pattern before this point.[61] All three chambers were overseen by a prince du sang with one of them the responsibility of the cardinal de Vendôme, one the responsibility of the cardinal de Bourbon and the final the responsibility of the marquis de Conti.[26][61] The technical specialists were distributed across the three chambers.[64] Henri entrusted the duc de Nevers with delivering a harangue to the nobility.[54] The notables were presented with a program of 217 articles which touched on all aspects of administration in the kingdom. The notables drew up reports on the various mechanisms by which the identified ills could be staunched.[4]

During December, Henri resolved to send out new commissioners into the provinces to see to the regulation of the collection of the taille, both through the clamping down of incorrect exemptions and to stop abuses committed by those who collected the tax.[66] The punishment for fraudsters would be established in April 1584 at the value of five years of the tax, with the examination concerning itself with the records of 1583 out of suspicion that the guilty parties might try to reform their ways with the investigation arriving in 1584.[67] This provoked protest from the Estates of Normandie, and Henri conceded to their priveliges.[68]

Henri and his mother Catherine actively participated in the sessions of the notables.[35] Catherine departed to meet with the duc d'Alençon at Château-Thierry on 31 December. Alençon was once again threatening the prospect of a civil war. The prince had apparently been convinced by 'malicious' members of his entourage, that Henri intended to withdraw from Alençon his prerogatives over his appanage as a way of recovering the royal domain. Catherine denied that Henri intended such, but this was not satisfactory for Alençon who demanded Henri respond to a point by point memorandum of his grievances.[69] In addition to this, Alençon was negotiating with deputies from the Dutch Staten (States) who requested the open support of Henri for his brother. Catherine stayed two weeks but could accomplish little in this regard without Henri's backing.[70]

A couple of members of the provincial estates who had not departed from the court and continued to challenge the king were silenced or imprisoned (as was the case with a Norman deputy who asserted that the French people could break their contract with the king, who had in his opinion already violated it) towards the end of December.[43]

On 12 January Henri recalled the duc de Nevers to the Assembly in the hopes this would facilitate the success of the Assembly.[64]

Proposals of the notables

[edit]In contrast to the grand ordonnance de Blois, the proposals made by the Notables would seek to reform as opposed to codify. The grand ordonnance of 1579 was respected.[71]

Church and nobility

[edit]The first three areas of proposals raised by the notables discuss areas which did not make it into the final printed version of the deliberations. That concerning the church reflects the opinions of the duc de Nevers, seigneur de Pons, the baron de Cessac; concerning the nobility the opinions of Nevers, Ponts, Pons and the seigneur d'Abain; as concerned justice the opinions of Nevers, Pons, the comte de Suze and the archbishop of Vienne.[72]

As regards the church, the notables expressed their suspicion of the upper crust of the ecclesiastical hierarchy. Support was given for something of a redistribution of the benefices of the church to enable the continued existence of the rural priests. Priests and higher prelates were to reside in their charges and an itinerant commission was to resolve conflicts caused by the recovery of church property. Nevers hoped that by these means, France's spiritual life could be revived.[72]

As regarded the nobility nothing new was proposed be the notables. Beyond a maintenance of the existing system of precedence and distinction.[72]

Royal justice

[edit]As regarded royal justice, the notables were concerned about the proliferation of venality. Given it would not be possible to reimburse all the office holders immediately to remove them, instead the offices could disappear on the present holders death.[72] To resolve looking improper in trials concerning the tax farms, Nevers proposed that instead of such cases being evoked to the conseil d'État that they rather remain in the ordinary courts. Nevers noted that the present process was viewed very cynically by the people. In addition to this change, it was proposed that the legal costs be reduced.[73]

For matters related to the crime of lèse majesté, Henri had little interest in the Assembly debating the substance of his proposals. Rather he sought their guidance as to the execution of the policy. Henri defined lèse majesté as the following crimes and more: a crime against the king and his authority; the unauthorised raising of soldiers, munitions and funds; the production of counterfeit currency; the fortification of private houses; exporting from France without permission gold, silver, wheat or wine; royal officials or prelates leaving the kingdom without Henri's permission and finally common people becoming pensioners of foreign powers.[73] He received little pushback from the notables on the substance, but in regards to a uniform policy of punishment there was disagreement from the notables. They argued that a uniformly strict policy would cause revolt and a uniformly forgiving policy would destroy Henri's authority. Therefore they proposed Henri reserve strict enforcement of the lèse majesté law for those crimes that were more serious, attacks on the king and his authority, the raising of troops and moneys, and the production of counterfeit currency.[63]

Military

[edit]As concerned the military, the notables were concerned by the poor state of the compagnies d'ordonnance which had been deteriorated by weak training and discipline, alongside poor payment. The result of this was to leave the soldiers not much better than brigands. Thus the body required rejuvenation.[63] While the notables stressed their desire to see Henri lead a large army, this had to be counterbalanced by the poverty of the treasury and need for a well paid soldiery. Thus 2,400 hommes d'armes (men-at-arms) would be enough, compacted into a few large well manned companies. Henri could thus reduce the number of his compagnies, by paying off the existing commanders if necessary.[74][35]

They approved of the integrating of the hommes d'armes with archers. They proposed various age thresholds different men in the body would have to attain before they could serve in a particular position (for example, the capitaines could be no younger than 30). These compagnies would spend four months a year garrisoned during which they could undertake the appropriate training.[74]

Economy and the domain

[edit]Many of the resolutions reached by the Notables concerned matters of the economy and finance.[75][16]

Henri had enquired of the notables how to approach the management of the royal domain. The assembly opined that through the recovery of the royal domain, the king could well disposed the people to him. They were of the opinion Henri was being taken for a ride in this matter by his financiers. There were three categories of alienated domain they discussed, that which was leased out, that which had been usurped, and that which had been committed. For the elements of the domain that the crown had leased out they advised a reworking of the leases, with Henri taking back the territory in return for compensation being delivered to the current holder. For that which had been usurped they advised against looking to local prosecutors (whose interests were tied to nearby grandees) to deal with the trouble but rather turn to a man of his own. Finally, those alienated domains over which Henri had the right of repurchase the notables argued that given the returns the holders enjoyed were excessive (above the 8.33% they should expect), they argued it was thus reasonable for the estates to be re-auctioned to a new farmer, who would then provide the first holder an annuity of 8.33% of the first purchase price. In such scenarios as the royal domain was small, and surrounded by privately held land, alienation was not objectionable to the notables.[76][26][77]

As concerned the aides (excise taxes) the notables did not council removing the exemptions that Parisians enjoyed from them, but rather proposed introducing a limit on the amount of wine they were allowed to sell.[78] Going forward they argued against allowing for further exemptions.[79]

They were of the opinion he could increase the rates for the farms (a method of tax generation by which rights to collect the tax were auctioned to the bidder who offered the king the largest sum for the right, this bidder was then authorised to collect the tax, with their profit being collection above the amount originally afforded to the king) with particular attention on the gabelle.[77] Tax farmers had attempted to limit the publicity of the auctions and prey on the crowns financial embarrassment to secure the acceptance of lowest price for the farm.[80] For the gabelle in particular, the involvement of many of the royal favourites and the sister of the queen with the tax had, in the opinion of the notables, allowed them to secure an overly favourable rate. Further with impunity assured before the parlements, the farmers fraudulently and violently extracted far more tax than they were meant to.[80]

As concerned the large tax farms, such as the customs of Lyon, the salt water fish farm, the farms concerned with the draperies and more, the notables argued that popular opinion had it that these farms were gouged with profits. To quash such disquiet the leases should therefore be put back up for auction. They further noted complaints from merchants about the many different taxes and custom duties that impeded their ability to do business. As a result of this they suggested the king consider potentially rationalising the farming system either under a single farmer or perhaps one per province. Before executing this policy further examination by specialists would be required.[79]

There were specific recommendations from the notables as regarded the grand parti du sel, a farm of salt which covered the areas around Paris, Rouen, Tours, Bourges, Orléans, Amiens, Dijon, Caen and the comté de Blois, a reexamation of the terms of the lease would be required. Auvergne should be brought into the paying fold, by this means eliminating salt workers who operated outside the system and contributing 150,000 livres to the treasury.[79][26]

In response to the king's concerns about potential abuses of the taille (land tax), the notables saw the only path forward to avoid the collectors favouring certain parishes over other ones would be for trésoriers généraux to take with them on their travels records of the tailles of the previous year so that they might assess the fairness.[81] When false exemptions from the taille were established, the punishment should be corporal. The trésoriers généraux would have to keep up to date lists of exemptions which would be rigorously checked with regularity.[82][83]

By all the above means, in particular the more favourable auctioning of the large farms, the king's debts could be successfully reduced. The notables were favourable to Henri's proposal to establish a private chamber of justice to prosecute embezzlers. They also opined approvingly on dramatically curtailing the number of financial officers.[82]

Cities

[edit]It was proposed that certain emergency measures be installed to ensure obedience to the complex web of laws. To this end six juges de police (police judges) should be established in every city with a parlement, receiving election annually. These six would be composed of a parlementaire, a présidial, an officer, a man of the church and two men of the town. In those towns without a parlement there would be four such juges (a magistrate, a man of the church and two men of the town). Under the purview of these figures would be matters of regulations. They would have the power to oversee the corporal punishment of the lower classes and fines of up to six écus. More serious offenses would not be within their remit and would rather require referral to the parlement.[84][83]

There were many problems facing the cities that the notables concerned themselves with: security, hygiene, disease, begging, and preparations for potential famines. The notables argued it should be the cities duty to maintain and improve the roads. The cities should also establish permanent medical officers. To deal with the 'problem of begging' the example of Lyon was to be followed by which public assistance was afforded through tax and alms, with orphans being offered apprenticeships.[83] The idea of eliminating retail merchants (who were often seen as responsible for the high prices of food in the cities) through the establishment of municipal food stores was floated.[84] The notables rejected this proposition, arguing that municipal stocks of food could not properly satisfy the people's desires, and would only be appropriate for basic staples like grain.[85][83] They likewise rejected a uniform tax rate on things such as the wages of servants and inns, instead proposing the aforementioned juges meet with the notables of the towns every six months to set the various rates. Similarly rejected was the setting of urban rents by the crown on the grounds it would induce a housing crisis.[85]

Industry

[edit]It was of great importance in the opinion of the notables that French manufacturing be revitalised. This would both enrich the kingdom, and reduce the 'level of vice' produced by 'idleness and poverty'. As concerned the cloth industry, which through a combination of tax and war had declined from being a 'great industry' of the kingdom, the notables proposed firstly the prohibition on the export of wool, hemp and linen. Similarly the important of foreign cloth was to be prohibited. This would stem the loss of 2,000,000 livres which went each year to the purchase of foreign Italian silk. While it would not be possible to ban English cloth from France due to treaties with the kingdom, the price of their merchandise could be set so low that they would not sell it. The notables argued this was the policy England used for French goods. Those raw materials that France lacked should be imported without the imposition of duties: wool, linen, hemp, wax, cochineal and so forth. Concessions should be employed to attract foreign workers, in particular Italians who could well support French industry.[85][86][83][30][75]

More horses should be bred due to the cost of importing them.[85] This should be done without setting the prices of imported horses down to a low level as this would just scare off the sellers.[87] Rather royal stud farms should be established across the kingdom, in any abbey that enjoys an income greater than 2,000 livres a stallion and four mares would be expected. They also proposed a 'practice of the gentleman of Brasil'.[62]

Some notables argued that German experts should be brought in to aid the exploitation of France's mineral wealth.[62]

General order

[edit]As concerned the maintenance of order in the kingdom at large, Henri wished to examine the roles of the various officials whose responsibility it was: the gouverneurs, lieutenants-généraux, baillis, sénéchaux and the prévôts des maréchaux (governors, lieutenant-generals, baillifs, seneschals and provost marshals).[62] He was unable to get a clarity of answer from the notables on this point. The notables did opine that the gouverneurs should enjoy their office as a commission, and that they should be reassigned every three years. When absent from their charge, the lieutenant-général should take charge in their place. The notables demonstrated a hostility towards the office of the prévôts des maréchaux which Karcher attributes to the role of some of these office holders in banditry particularly in the south.[88]

In summary, Henri asked the notables for the best means by which their above recommendations could be brought into real practice. The notables proposed using extraordinary means to bring about the passage of the decisions. Those who enjoy power and stewardship in the area would be expected to provide Henri reports on the progress of affairs as related to their area: for the church grandees, this would be every year, for the governors every quarter and so on.[88]

End of the Assembly, and legacy

[edit]Closure of the Assembly

[edit]The final working session of the Assembly appears to have been undertaken on 31 January.[35] On this day, Catherine departed from Saint-Germain.[26][89]

The exact end date of the Assembly is unknown, however Henri's work at Saint-Germain concluded on 15 February with his return to Paris.[54][56][89]

Salmon sees the Assembly of Notables of 1583 as embodying the spirit of bureaucratic absolutism.[90]

Legislative legacy in 1584–1585

[edit]The proposals that had been submitted by the three chambers to the king were carefully compiled into an official text, then published.[89] This text only preserves the findings of the chamber chaired by the cardinal de Vendôme. Karcher argues it is likely there was little substantive difference between what Henri would have received from the three chambers, but that perhaps it was more complete or more favourable to the king than the other two.[91]

The parlementaire Barnabé Brisson was tasked with collating all the edicts and ordonnances that were presently in force. He would publish the work, a sophisticated legal synthesis that became known as the Code Henri III and was published in May 1587.[35][11]

Much of Henri's legislation in 1584 and 1585 would embody the proposals of the Assembly. As early as 6 January Henri announced to the capitaines de compagnies de cent hommes d'armes (captains of companies of 100 men-at-arms) that he was cutting the size of their compagnies in half so that the men in them could be better paid. He assured the capitaines that their pay would remain the same.[68] This was followed on 23 January by a new regulation on the prévôts des maréchaux and their subordinates.[92] On 9 February he issued a grand ordonnnance re-organising the royal gendarmerie.[35] Articles concerned themselves with their pay, garrison duty and the behaviour of the soldiery towards civilians.[92] Article 40 of the ordonnance allowed commoners access to the compagnies d'ordonnance. Their pay was to be made more efficient.[93] In March Henri issued an edict on the admiralty which discussed the judicial and administrative aspects of maritime affairs across 100 articles, then in December an edict concerning the colonel-général de l'infantrie (colonel-general of the infantry).[94][92]

Henri instituted a 'spirit of economy' in the court, reducing its schedule and expenditure in a manner that caused grief among his courtiers. No longer would Henri splash large sums of money on his favourites. The ambassador of the Holy Roman Emperor reported in February 1584 on Henri's decision to stay in Saint-Germain during the conduct of carnival festivities in Paris, describing Saint-Germain as being a place 'more suitable for retirement'.[95][96] Various offices were for a brief time suppressed towards the aims of ending venality.[97]

Royal debts were to be liquidated, with a proportion of the rentes repurchased. Government stock was to be lowered.[93]

Measures to improve the condition of hospitals were established. Begging and banditry would be curtailed. Those who were orphaned, old or disabled were to receive the support of a municipal tax so as to better.[93]

The leases for the farming of indirect taxes were increased in value, changes were also made to the taille and gabelle.[6] On 28 January the lease to Houdry of the prévôté of Nantes was revoked. This was followed on 4 February by the returning of the farm for the sale of salt water fish in Paris to its former farmer but at an elevated rate of 22,000 écus instead of 18,000 écus.[98] The lease of the five large tax farms (the customs of Lyon, part of the import and export duties, and the domestic taxes on cloth and wine) was annulled (despite great protest from the lease holders - one of whom enjoyed the backing of the Gondi) and then consolidated into a single lease which was awarded on 24 May 1585 at a more favourable rate for the crown to three financiers (René Brouart a bourgeois of Paris, and the Italians Tomasso Sardini and Jean-Baptiste de Gondi).[75][3][95][99] As a result of the lease, Brouart was to enjoy for eight years beginning in October 1584 the rights to the farms. He would pay 359,833 écus a year, and advance the king 60,000 écus.[100] The money advanced to the king by Brouart as a result of this allowed Henri to pay his officers incomes, service the royal annuities and settle some of the crowns debts.[101] Due to the fact the lease had been usurped from its previous holders, the lease-holders were to pay off 666,389 écus to them, and pay the king 359,833 écus per year. This was a considerable success for the king.[102] Pernot sees this move as the first step taken by the French crown towards the general tax farm of 1680.[66] Karcher argues that the farms de-facto remained in the hands of the same financiers but that Henri was able to increase his revenues.[100]

The royal assault on the gabelle 'party' was less successful, and abuses remained numerous. Henri wanted to put it out to a new bidder and if none could afford the entirety of the farm, to break it down into smaller pieces, however he was strongly resisted in this by members of his conseil and high finance. On 29 April, Henri tasked Cheverny with putting together a commission to end embezzlement abuses of the gabelle. Those of Provence, Dauphiné and Languedoc would be subject to an investigation by André Maillard from the cour des aides from 1583 to December 1584.[100] Maillard was subject to protest from one of the leaseholders of salt who was concerned by requests to see his accounts and observe his agents.[103] In December 1584, the gabelle which was a very unpopular tax, was withdrawn from all areas in which it had not existed before the farm had been given to the financier Faure.[94] Well aware of how toxic the tax was with his subjects, Henri reduced the money the farmer Champin was to provide him by 50,000 écus so as to ease the burden on the people.[68]

On 29 May 1584, Henri declared the creation of a special chamber of justice to examine abuses committed by tax farmers and financial officials.[6][75] Pernot argues the body was less concerned with providing a just financial regimen than it was imposing fines and providing satisfaction to the people, it would order arrests and confiscations. On 9 June Cheverny went to the parlement to preside over the first session of the new chamber. Confiscations, arrests and even death penalties were declared by the body, which attempted to even go after powerful financiers like Sardini.[102] Nevertheless, the most powerful financiers like Faure (a former farmer of the gabelle) and Sardini avoided prosecution, while Wideville was allowed to flee abroad.[104] The body was more effective against the 'small fry'. Henri turned a blind eye to Wideville's flight due to the discreet financial services he had provided in prior times.[102] A special chamber was also established in Rouen to deal with trials that concerned the reform of the royal forests.[67]

In conseil on 29 July 1584 it was declared that the taille would be reduced by 250,452 écus. This reduction was made public on 29 March 1585.[105]

On 14 November, Henri ordered that the trésoires généraux provide him reports every six months. The chambre des comptes of Provence sent a report on the principauté d'Orange to the royal conseil by which they argued that the French king enjoyed sovereignty over the small domain.[67] Karcher notes that the new regulations of the court promulgated on 1 January 1585 were written by the king's own hand.[98]

By edict of November 1584 many financial offices were abolished. However this failed to account for the complexity of the financial administration, and later many of the offices would be re-established.[68]

Spending was restricted and this delivered results. In the provincial Estates of Normandie at the end of 1584 the cahiers recorded the fruits of these efforts in a growing confidence. In 1585 the royal budget was almost balanced (with the deficit reduced to the minimal value of 363,732 écus when compared with the 1584 deficit of 1,800,000 écus).[69] Henri ordered a breakdown of the remaining deficit in all areas except for those concerning the security of the state (the army, navy, mercenaries and embassies).[94] Of course, the state's overall deficit remained vast, and the redemption of the royal domain incomplete, but if several years of internal peace would follow, it offered the possibility of success.[104] However the crisis of the Catholic ligue (league) would destroy these victories.[16] In addition to the ligueur crisis, the fundamental issues of the tax system remained unaddressed, and those who paid the taxes found themselves increasingly unwilling to pay them. At court, expenditure was also difficult to control.[106]

Long term legacy

[edit]During the Seventeenth and Eighteenth centuries, the conclusions of the 1583 Assembly of Notables were viewed as an impressive feat, which had only been sabotaged from delivering the benefits it was supposed to by the political circumstances of the time. In 1623 a mémoire highlighted them as a model for Louis XIII to follow.[71]

Sources

[edit]- Boltanski, Ariane (2006). Les ducs de Nevers et l'État royal: genèse d'un compromis (ca 1550 - ca 1600). Librairie Droz.

- Boucher, Jacqueline (2023). Société et Mentalités autour de Henri III. Classiques Garnier.

- Carpi, Olivia (2012). Les Guerres de Religion (1559-1598): Un Conflit Franco-Français. Ellipses.

- Chevallier, Pierre (1985). Henri III: Roi Shakespearien. Fayard.

- Cloulas, Ivan (1979). Catherine de Médicis. Fayard.

- Holt, Mack (2002). The Duke of Anjou and the Politique Struggle During the Wars of Religion. Cambridge University Press.

- Jouanna, Arlette (1998). "Le Temps des Guerres de Religion en France (1559-1598)". In Jouanna, Arlette; Boucher, Jacqueline; Biloghi, Dominique; Le Thiec, Guy (eds.). Histoire et Dictionnaire des Guerres de Religion. Éditions Robert Laffont.

- Jouanna, Arlette (2021). La France du XVIe Siècle 1483-1598. Presses Universitaires de France.

- Karcher, Aline (1956). "L'assemblée des notables de Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1583)". Bibliothèque de l'École des chartes. 114.

- Knecht, Robert (2014). Catherine de' Medici. Routledge.

- Knecht, Robert (2016). Hero or Tyrant? Henry III, King of France, 1574-1589. Routledge.

- Le Roux, Nicolas (2022). 1559-1629 Les Guerres de Religion. Gallimard.

- Mariéjol, Jean H. (1983). La Réforme, la Ligue, l'Édit de Nantes. Tallandier.

- Pernot, Michel (1987). Les Guerres de Religion en France 1559-1598. Sedes.

- Pernot, Michel (2013). Henri III: Le Roi Décrié. Éditions de Fallois.

- Reulos, Michel (1992). "L'Action Législative de Henri III". In Sauzet, Robert (ed.). Henri III et son Temps. Librairie Philosophique J.Vrin.

- Salmon, J.H.M. (1979). Society in Crisis: France in the Sixteenth Century. Metheun & Co.

- Sutherland, Nicola (1962). The French Secretaries of State in the Age of Catherine de Medici. The Athlone Press.

References

[edit]- ^ Salmon 1979, p. 226.

- ^ Salmon 1979, p. 227.

- ^ a b Jouanna 1998, p. 283.

- ^ a b c d Carpi 2012, p. 368.

- ^ Pernot 1987, p. 117.

- ^ a b c d e Pernot 1987, p. 118.

- ^ a b Le Roux 2022, p. 241.

- ^ Karcher 1956, p. 118.

- ^ a b Chevallier 1985, p. 514.

- ^ Salmon 1979, p. 228.

- ^ a b Reulos 1992, p. 179.

- ^ a b c d e Chevallier 1985, p. 515.

- ^ a b Karcher 1956, p. 119.

- ^ a b Pernot 2013, p. 309.

- ^ Karcher 1956, p. 120.

- ^ a b c d e Jouanna 2021, p. 568.

- ^ a b c Karcher 1956, p. 121.

- ^ Karcher 1956, pp. 120–121.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Carpi 2012, p. 367.

- ^ Cloulas 1979, p. 477.

- ^ Knecht 2016, p. 221.

- ^ a b c d e Knecht 2016, p. 222.

- ^ a b Karcher 1956, p. 122.

- ^ a b c d e f Salmon 1979, p. 229.

- ^ a b c Karcher 1956, p. 124.

- ^ a b c d e f g Chevallier 1985, p. 516.

- ^ a b c d Karcher 1956, p. 125.

- ^ Boucher 2023, p. 647.

- ^ Sutherland 1962, p. 243.

- ^ a b c d Pernot 2013, p. 310.

- ^ a b Karcher 1956, p. 134.

- ^ a b Karcher 1956, p. 135.

- ^ a b c d Carpi 2012, p. 369.

- ^ a b Cloulas 1979, p. 468.

- ^ a b c d e f Cloulas 1979, p. 478.

- ^ a b Karcher 1956, p. 126.

- ^ a b Karcher 1956, p. 127.

- ^ a b Mariéjol 1983, p. 260.

- ^ Salmon 1979, p. 303.

- ^ a b c d e Knecht 2016, p. 223.

- ^ Karcher 1956, p. 129.

- ^ Karcher 1956, p. 128.

- ^ a b c Karcher 1956, p. 130.

- ^ Knecht 2016, p. 179.

- ^ Cloulas 1979, p. 469.

- ^ a b Holt 2002, p. 201.

- ^ Knecht 2014, p. 214.

- ^ a b Cloulas 1979, p. 472.

- ^ a b c d Karcher 1956, p. 133.

- ^ Karcher 1956, p. 131.

- ^ a b c d e f g Karcher 1956, pp. 130–132.

- ^ Le Roux 2022, p. 231.

- ^ Karcher 1956, pp. 131–132.

- ^ a b c Boltanski 2006, p. 414.

- ^ Le Roux 2022, pp. 242–243.

- ^ a b c Le Roux 2022, p. 242.

- ^ Karcher 1956, p. 123.

- ^ a b c Karcher 1956, p. 136.

- ^ a b c d e Karcher 1956, p. 137.

- ^ Karcher 1956, pp. 137–138.

- ^ a b c d e Karcher 1956, p. 138.

- ^ a b c d Karcher 1956, p. 152.

- ^ a b c Karcher 1956, p. 145.

- ^ a b c Karcher 1956, p. 139.

- ^ Cloulas 1979, p. 473.

- ^ a b Pernot 2013, p. 311.

- ^ a b c Karcher 1956, p. 159.

- ^ a b c d Karcher 1956, p. 160.

- ^ a b Cloulas 1979, p. 480.

- ^ Holt 2002, p. 203.

- ^ a b Karcher 1956, p. 142.

- ^ a b c d Karcher 1956, p. 143.

- ^ a b Karcher 1956, p. 144.

- ^ a b Karcher 1956, p. 146.

- ^ a b c d Cloulas 1979, p. 479.

- ^ Karcher 1956, p. 147.

- ^ a b Mariéjol 1983, p. 262.

- ^ Karcher 1956, pp. 147–148.

- ^ a b c Karcher 1956, p. 148.

- ^ a b Mariéjol 1983, p. 263.

- ^ Karcher 1956, pp. 148–149.

- ^ a b Karcher 1956, p. 149.

- ^ a b c d e Chevallier 1985, p. 517.

- ^ a b Karcher 1956, p. 150.

- ^ a b c d Karcher 1956, p. 151.

- ^ Mariéjol 1983, p. 261.

- ^ Karcher 1956, pp. 151–152.

- ^ a b Karcher 1956, p. 153.

- ^ a b c Karcher 1956, p. 140.

- ^ Salmon 1979, p. 231.

- ^ Karcher 1956, p. 141.

- ^ a b c Karcher 1956, p. 161.

- ^ a b c Salmon 1979, p. 230.

- ^ a b c Chevallier 1985, p. 520.

- ^ a b Chevallier 1985, p. 518.

- ^ Knecht 2016, p. 224.

- ^ Salmon 1979, pp. 230–231.

- ^ a b Karcher 1956, p. 155.

- ^ Karcher 1956, p. 156.

- ^ a b c Karcher 1956, p. 157.

- ^ Carpi 2012, p. 370.

- ^ a b c Chevallier 1985, p. 519.

- ^ Karcher 1956, p. 158.

- ^ a b Pernot 2013, p. 312.

- ^ Karcher 1956, p. 162.

- ^ Jouanna 1998, p. 284.