2012 Venezuelan presidential election

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 80.52% | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

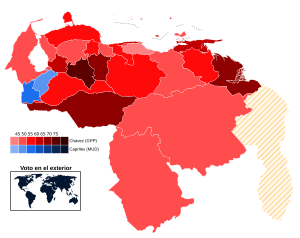

Results by state | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

|

|---|

|

|

Presidential elections were held in Venezuela on 7 October 2012 to choose a president for a six-year term beginning in January 2013.[1]

After the approval of a constitutional amendment in 2009 that abolished term limits, incumbent Hugo Chávez, representing the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) was able to present himself again as a candidate after his re-election in 2006. His main challenger was Henrique Capriles, Governor of Miranda, representing Justice First. The candidates were backed by opposing electoral coalitions; Chávez by the Great Patriotic Pole (Gran Polo Patriótico, GPP), and Capriles by the opposition Democratic Unity Roundtable (MUD). There were four more candidates from different parties.[2] Capriles ran an energetic campaign, and visited each of the country's states. Throughout his campaign, Capriles remained confident that he could win the election and be the country's next President[3] despite Chávez leading most polls by large margins. Chavez won the election comfortably, although this was the narrowest margin he ever won by.

Chávez was elected for a fourth term as President of Venezuela with 55.07% of the popular vote, ahead of the 44.31% of Capriles.[4] The elections showed a turnout of above 80%.[5] Capriles conceded defeat as the preliminary results were known.[6] Chávez died only two months into his fourth term.

Electoral process[edit]

Since 1998 elections in Venezuela have been highly automated,[7] and administered by a non-partisan National Electoral Council, with poll workers drafted via a lottery of registered voters. Polling places are equipped with multiple high-tech touch-screen DRE voting machines, one to a "mesa electoral", or voting "table". After the vote is cast, each machine prints out a paper ballot, or VVPAT, which is inspected by the voter and deposited in a ballot box belonging to the machine's table. The voting machines perform in a stand-alone fashion, disconnected from any network until the polls close.[8] Voting session closure at each of the voting stations in a given polling center is determined either by the lack of further voters after the lines have emptied, or by the hour, at the discretion of the president of the voting table.

Formal registration[edit]

On 10 June 2012, Capriles walked to the election commission to formally register his candidacy, at the head of a march estimated in the hundreds of thousands by international media, while local polling company Hernández Hercon estimated it to between 950,000 and 1,100,000. Capriles had stepped down as Governor of Miranda in early June in order to concentrate on his campaign.[9][10][11][12]

Withdrawals[edit]

17 September, opposition candidate Yoel Acosta Chirinos withdrew from presidential election and announced support to president Chavez.[citation needed]

Parties[edit]

Patriotic Pole[edit]

Incumbent president Hugo Chávez Frías announced he would seek re-election at a University Students' Day rally held in Caracas in November 2010. Chávez' first mandate began in 1999, and if he had served the complete 2013–19 term, he would have served 20 years as president,[13] having won four presidential elections. In July 2011, Chávez reaffirmed his intent to run in spite of his battle with cancer.[14]

Chávez was supported by the Great Patriotic Pole (GPP), an electoral coalition led by the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela, PSUV).[citation needed]

Democratic Unity[edit]

The opposition parties were grouped in the Democratic Unity Roundtable whose candidate was selected through an open primary election held on 12 February 2012.[15] The MUD electoral coalition consists of the parties Justice First (Movimiento Primero Justicia, PJ), Fatherland for All (Patria Para Todos, PPT), Project Venezuela (Proyecto Venezuela), and Popular Will (Voluntad Popular, VP) as the main supporters of Henrique Capriles in the primary elections of February 2012.[15] Other parties in the coalition include A New Era (Un Nuevo Tiempo, UNT), Democratic Action (Acción Democrática, AD), COPEI (Comité de Organización Política Electoral Independiente), and Movement to Socialism (Movimiento al Socialismo, MAS).[16]

Primary[edit]

-

Governor Henrique Carpiles Radonski of Miranda

-

Governor Pablo Pérez of Zulia

-

Deputy María Corina Machado of Miranda

-

Former Mayor Leopoldo López of Chacao (Withdrew on 20 February 2012)

Capriles won the opposition primaries with 1,900,528 (64.2%) votes of the 3,059,024 votes cast (votes abroad not included).[17] The other candidates on 12 February primary ballot were:

- Pablo Pérez Álvarez: governor of Zulia state, representing the A New Era party; received 30.3% of the vote.[17]

- María Corina Machado: former Súmate president and member of the National Assembly of Venezuela representing the Miranda state since 2011; received 3.7% of the vote.[17]

- Diego Arria: former Venezuelan representative to the United Nations (1990–91) and former governor of the defunct Federal District (1974–78); received 1.3% of the vote.[17]

- Pablo Medina: politician and former trade union leader; received 0.5% of the vote.[17]

Leopoldo López was barred from running following corruption charges which he denied and for which he was never tried; in 2011, the Interamerican Court of Human Rights overturned the Venezuelan government ruling and said he should be allowed to run.[18][19] On 24 January, placed "in the awkward position of being able to stand for elections but not hold office",[18] he withdrew his candidacy to support Henrique Capriles.[20][21]

Candidates César Pérez Vivas (governor of Táchira state), Antonio Ledezma (mayor of the Metropolitan District of Caracas) and Eduardo Fernández (former secretary general of COPEI) withdrew from the race, saying they would support candidates with better chances of winning.[22]

Voter list dispute[edit]

A dispute erupted over the disposition of the voter rolls, rising out of concern that opposition voters could incur reprisals.[23][24] Because the names of voters who had participated in the request of the 2004 recall referendum against Chávez had been made public via the Tascón List and, according to opposition leaders, those voters were later targeted for discrimination or lost jobs, the MUD had guaranteed voter secrecy.[23][24] On Tuesday 14 February, in response to "a losing mayoral candidate, who asked that the ballots be preserved for review",[25] the Supreme Court of Venezuela ordered the military to collect the voting rolls "so that electoral authorities could use them to investigate alleged irregularities during Sunday's elections".[23]

An attorney for the opposition said that records are to be destroyed within 48 hours by law.[23] Violence broke out as the opposition attempted to prevent police from collecting the names of voters. One young man, Arnaldo Espinoza, was run over and killed by a police tow truck that backed up suddenly, attempting to separate people who were protecting the vehicle belonging to the vice-president of the regional office for the primary elections in the state of Aragua.[26] Later the opposition declared all voter rolls had been destroyed.[23][24]

Candidate platforms[edit]

Chávez[edit]

The GlobalPost says that "housing, health and other programs have been the cornerstone" of President Chávez's tenure, who "remains very popular, largely because of the vast number of social programs he put in place, funded by Venezuela's vast oil wealth".[18] According to The Washington Times, Chávez said the opposition represents "the rich and the U.S. government"; as part of his campaign, he increased social spending and investments to benefit the poor, and plans to launch a satellite made in China before the elections.[27]

Capriles[edit]

According to Reuters, "Capriles defines himself as a center-left 'progressive' follower of the business-friendly but socially-conscious Brazilian economic model",[28] although he is a member of the center-right[29][30][31] Justice First. He has a youthful and populist style, a sports enthusiast who rides a motorbike into the slums, and has broken with the older guard of Venezuelan politicians.[32] Although he comes from a wealthy family, he espouses helping business thrive through a free market while tackling poverty via strong state policies.[32] In an interview with the GlobalPost, Capriles said his campaign was based on "improving education, which he sees as a long-term solution to the country's insecurity and deep poverty".[18] In November 2011, in response to claims from Chavez that the opposition would end the Bolivarian Missions if elected, Capriles said "he would be 'mad' to end" projects like Mission Barrio Adentro, adding that "the missions belong to the people".[33] In February 2012 Capriles insisted he would keep these programs, saying "I want to expand them, and get rid of the corruption and inefficiency that characterizes them."[34]

In early September 2012 David De Lima, a former governor of Anzoátegui, published a document that he said that showed secret MUD plans to implement, if elected, different from what their public statements showed. De Lima said the document was a form of policy pact between some of the candidates in the MUD primary, including Capriles.[35] On 6 September 2012 opposition legislator William Ojeda denounced these plans and the "neoliberal obsessions" of his colleagues in the MUD;[36] he was suspended by his A New Era party the following day.[37] Capriles said that his signature on the document was a forgery,[citation needed] while the MUD's economic advisor said that the MUD had "no hidden agenda", and that its plans included the "institutionalisation" of the government's Bolivarian Missions so that they would no longer be "subject to the whims of government".[38] One small coalition party claimed De Lima had offered them money to withdraw from the MUD;[39] De Lima denied the claim.[40]

Campaign[edit]

The authority of the Venezuelan National Electoral Council (CNE) to oversee the election was recognized by the opposition.[27] Chávez said the fairness of the CNE should not be challenged.[27] The Wall Street Journal (WSJ) noted Chávez's popularity among poor Venezuelans, and that "Chávez dominates the nation's mass media, and has been spending lavishly on social programs to sway Venezuelan voters".[25] A January poll placed Chávez's approval rating at 64 percent.[18] In May Rafael Poleo, owner and publisher of El Nuevo País, warned in a column in his newspaper that the MUD candidacy was lagging in the polls because it "ignores that in Venezuela voting is emotional ... and that the people vote for hope", adding that "Chavismo has taken the place in the heart of the people which AD and Copei have vacated." He concluded that "going down this road, I can already tell them the outcome."[41] Capriles criticized Chávez for expropriating private businesses and for the government's use of the state-controlled media; the Washington Times said it will be hard for Capriles to compete with Chávez's "ability to take over the airwaves of all TV and radio stations when he deems appropriate".[27] In June Chávez said he would not engage in an election debate with Capriles, describing him as a "non-entity" he would be "ashamed" to measure himself against.[42]

Funding[edit]

It has been reported that funds to social programs increased dramatically before the elections, with Chávez devoting 16% of Venezuela's GDP to the initiatives.[43]

Chávez's health[edit]

Prior to the election, Chávez received treatment for cancer in Cuba[44] including radiation, chemotherapy, and two operations.[45] In a Mass during Easter Week 2012, Chávez wept and asked Jesus Christ to give him life;[46] the Associated Press says that although Chávez often praised socialism and atheism, his cancer caused him to turn to Jesus Christ for inspiration and that "... analysts say his increasing religiosity could pay election-year dividends in a country where Catholicism remains influential".[45] He did not reveal the specifics of the type or location of his cancer, but his illness was a factor in election campaigning.[46]

According to Reuters, some journalists sympathetic to the opposition spread information about Chávez's cancer based on claims that they had access to medical sources.[47] Amid speculation about whether he will live through the elections, there was no clear successor.[44] CNN stated "outlines" of a successor were seen in the appointments of two Chávez allies to top posts;[44] Diosdado Cabello as president of the National Assembly of Venezuela and Henry Rangel Silva as minister of defense.[44] Reuters said additional potential successors or placeholders include Chávez's two daughters and Nicolás Maduro, foreign minister.[48] The Venezuelan constitution provides for the president to appoint vice presidents at his discretion, and for the vice president to assume power in the event of the president's death, but according to CNN, the more likely scenarios ranged "from a military coup to Chávez naming Cabello or Maduro vice president before he dies."[44] CNN also said that analysts say Cuban politics had a role in the succession questions, with some Cubans supporting the president's brother, Adán Chávez.[44]

From mid-April to late May 2012, Chávez was only seen in public twice, spending almost six weeks in Cuba for treatment.[47] On 7 May, he responded to criticism that he had left Venezuela in a power vacuum, saying he would be back soon.[48] On 22 May he took part in a live broadcast of a cabinet meeting lasting several hours.[49] He created a new Council of State, fueling rumors that it would act as a committee to help in the event a transition of government was needed.[47]

Allegations[edit]

In February 2012 Capriles was subject to what were characterized in the press as "vicious"[25] and "anti-semitic"[50] attacks by state-run media sources.[32][51] The Wall Street Journal said that Capriles "was vilified in a campaign in Venezuela's state-run media, which insinuated he was, among other things, a homosexual and a Zionist agent".[25] These comments were in response to an opinion piece on the website of the state-owned Radio Nacional de Venezuela, published on 13 February 2012, and to allegations broadcast on La Hojilla relating to an alleged sexual incident in 2000. Titled "The Enemy is Zionism"[52] the Radio Nacional opinion piece noted Capriles' Jewish ancestry and a meeting he had held with local Jewish leaders,[25][51][53] saying: "This is our enemy, the Zionism that Capriles today represents ... Zionism, along with capitalism, are responsible for 90% of world poverty and imperialist wars."[25] Capriles is the grandson of Jewish Holocaust survivors[53] and a self-professed devout Catholic.[25] The United States-based organisations Simon Wiesenthal Center and the Anti-Defamation League condemned the attacks and voiced concern to Chávez, who vowed in 2009 to punish incidents of antisemitism.[50][54]

In early July 2012 Capriles published a document allegedly showing that the government had ordered all military personnel not to view private television networks. The publication coincided with a Capriles political ad aimed at the military.[55] Based on non-classified military order 4926 from September 2011, the document had been redated to 31 July but was published several weeks before that date, still bearing the original signature of the minister of defense in September 2011, Carlos José Mata Figueroa (who had been replaced in January 2012). The document bore the original document number, and had the "not classified" stamps replaced with "confidential", but retained the original "NOCLAS" ("not classified") classification mark.[56]

Opinion polls[edit]

According to Reuters, "Polls are historically controversial in Venezuela", pointing out that "Venezuelan pollsters – who range from a former Chavez minister to an openly pro-opposition figure – also tend to double as political analysts, offering partisan opinions in state media or opposition-linked newspapers."[57] In addition, it said that "As in previous elections, a proliferation of little-known public opinion firms with no discernable track record have emerged from obscurity promoting polls that appear to openly favor one candidate or the other."[57] In June 2012 most pollsters showed Capriles behind by at least 15 percentage points, and intention to vote for Chávez slowly increasing since the end of 2011. One firm, Hinterlaces, was accused by Capriles of publishing "bogus polls".[57] The Chavez campaign accused Datanalisis and Consultores 21 of inventing polls to support opposition plans to claim fraud in the event of defeat.[57]

Although the poll results vary widely, most of the variation is by pollster; results from individual pollsters are quite stable over time. Of the established Venezuelan pollsters, Consultores 21 and Varianzas have consistently shown a close race, while IVAD, GIS XXI, Datanalisis and Hinterlaces have consistently given Chávez a 10 to 20-point lead.

In June the CNE required pollsters publishing polls relating to the election to register with them, and to provide details of their methodology.[58] The list of registered pollsters is available online.[59]

Established Venezuelan pollsters[edit]

| Pollster | Publication date | Chávez | Capriles | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hinterlaces[60] | Jan 2012 | 50 | 34 | [61] |

| IVAD[62] | Feb 2012 | 57 | 30 | [63] |

| Hinterlaces | Mar 2012 | 52 | 34 | [64] |

| IVAD | Mar 2012 | 56.5 | 26.6 | [65] |

| Consultores 21[66] | Mar 2012 | 46 | 45 | [67] |

| Datanálisis[68] | Mar 2012 | 44.7 | 31.4 | [69] |

| Varianzas | April 2012 | 49.3 | 45.1 | [70] |

| GIS XXI[71] | May 2012 | 57 | 21 | [72] |

| Varianzas | May 2012 | 50.5 | 45.7 | [73] |

| GIS XXI | June 2012 | 57.0 | 23.0 | [citation needed] |

| Consultores 21 | June 2012 | 47.9 | 44.5 | [74] |

| Hinterlaces | June 2012 | 51 | 34 | [42] |

| Consultores 21 | July 2012 | 45.9 | 45.8 | [75] |

| IVAD | July 2012 | 54.8 | 32.9 | [76] |

| Varianzas | July 2012 | 50.3 | 46.0 | [77] |

| Datanálisis | July 2012 | 46.1 | 30.8 | [78] |

| Hinterlaces | July 2012 | 47 | 30 | [79] |

| GIS XXI | August 2012 | 56 | 30 | [80] |

| Varianzas | August 2012 | 49.3 | 47.5 | [81] |

| Hinterlaces | 16 August 2012 | 48 | 30 | [82] |

| Datanálisis | 20 August 2012 | 46.8 | 34.2 | [83] |

| Consultores 21 | 24 August 2012 | 45.9 | 47.7 | [84] |

| IVAD | 2 September 2012 | 50.8 | 32.4 | [citation needed] |

| Hinterlaces | 6 September 2012 | 50 | 32 | [citation needed] |

| Consultores 21 | 19 September 2012 | 46.2 | 48.1 | [85] |

| Datanálisis | 24 September 2012 | 47.3 | 37.2 | [86] |

| Hinterlaces | 25 September 2012 | 50 | 34 | [87] |

Conduct[edit]

In March 2012, at a visit by Capriles to the San José de Cotiza Caracas neighbourhood, a group of armed members of the ruling United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) began firing guns "in an apparent effort to break up the rally".[88][89] According to news reports, five people were injured, including the son of an opposition member of the National Assembly of Venezuela. Capriles was subsequently taken safely from the scene. Journalists for television channel Globovisión had been covering the rally; its crew, consisting of reporter Sasha Ackerman, cameraman Frank Fernández and assistant Esteban Navas were threatened by the armed men, who confiscated their equipment and footage of the shootings.[88] A Globovisión statement the next day identified the armed men as PSUV supporters, saying "These groups wore red shirts identifying them with a political tendency. More importantly, it was an armed and organized group that fired weapons against people".[89] Venezuela's justice minister, Tarek El Aissami, accused opposition supporters of perpetrating the attacks "to generate this show", while other government officials claimed that Capriles' bodyguards "were the ones to start shooting".[89]

There have also been reports of opposition supporters attacking journalists at opposition campaign events, including reporter Fidel Madroñero for local public station Catatumbo Television at an event in the Zulia state,[90] and VTV reporter Llafrancis Colina at events in Aragua,[90][91][92] as well as in the Táchira and Barinas states.[93] Capriles subsequently told journalists "I'm against any type of violence, no matter where it comes from."[94]

PSUV politician Diosdado Cabello declared that Chávez was the only one who could guarantee peace. He added: "those who want fatherland will go with Chávez; those who are traitors will go with the others". He also said that if the opposition wins, it would take the measures of the IMF.[95]

Alleged plots[edit]

On 20 March Chávez declared he had intelligence reports about an alleged plot to assassinate Capriles, and said the government was monitoring security for Capriles, with the Director of the Bolivarian Intelligence Service meeting with Capriles' security team. Capriles responded that what the government should do is to guarantee security for all Venezuelans.[96] Chávez said that his government "has nothing to do with" the plot,[96] and according to Reuters, "implied that the plot came from elements in the opposition". Capriles' campaign manager said the announcement was intended to force a change in Capriles' house-by-house campaigning style.[97] In the 2006 presidential election, Chávez similarly declared he had uncovered an assassination plot against his opponent, Manuel Rosales.[32]

Later that same month, Chávez claimed the existence of an opposition plot to disrupt the election with violence and "attack ... the constitution, the people and institutions". Of the "list of actions" he said he was preparing in response, Chávez said he was willing to nationalise banks or companies that supported the opposition should they "[violate] the constitution and the national plan."[98]

In April, Chávez said Capriles was behind a conspiracy plan against his government. Reiterating that he would win with at least 70% of the votes, Chávez said that he had created a civil-military command to neutralize any "destabilization plans" in the event that the opposition did not recognise the results. In reference to the events of April 2002, Chávez said that if necessary, "there would not just be the people on the streets, but the people and soldiers".[99]

Results[edit]

| Candidate | Party | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hugo Chávez | Great Patriotic Pole | 8,191,132 | 55.07 | |

| Henrique Capriles | Democratic Unity Roundtable | 6,591,304 | 44.32 | |

| Reina Sequera | Workers' Power | 70,567 | 0.47 | |

| Luis Reyes | Authentic Renewal Organization | 8,214 | 0.06 | |

| María Bolívar | United Democratic Party for Peace | 7,378 | 0.05 | |

| Orlando Chirinos | Party for Socialism and Liberty | 4,144 | 0.03 | |

| Total | 14,872,739 | 100.00 | ||

| Valid votes | 14,872,739 | 98.10 | ||

| Invalid/blank votes | 287,550 | 1.90 | ||

| Total votes | 15,160,289 | 100.00 | ||

| Registered voters/turnout | 18,903,937 | 80.20 | ||

| Source: CNE | ||||

By party[edit]

| Candidate | Party or alliance | Votes | % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hugo Chávez | Great Patriotic Pole | United Socialist Party of Venezuela | 6,386,699 | 42.94 | ||

| Communist Party of Venezuela | 489,941 | 3.29 | ||||

| Fatherland for All | 220,003 | 1.48 | ||||

| Networks Party | 198,118 | 1.33 | ||||

| People's Electoral Movement | 185,815 | 1.25 | ||||

| Tupamaro | 170,450 | 1.15 | ||||

| For Social Democracy | 156,158 | 1.05 | ||||

| New Revolutionary Road | 121,735 | 0.82 | ||||

| Venezuelan Popular Unity | 89,622 | 0.60 | ||||

| Independents for the National Community | 69,988 | 0.47 | ||||

| Revolutionary Workers' Party | 58,509 | 0.39 | ||||

| Venezuelan Revolutionary Currents | 43,627 | 0.29 | ||||

| Other votes | 467 | 0.00 | ||||

| Total | 8,191,132 | 55.07 | ||||

| Henrique Capriles | Democratic Unity | Democratic Unity Roundtable | 2,204,962 | 14.83 | ||

| Justice First | 1,839,573 | 12.37 | ||||

| Un Nuevo Tiempo | 1,202,745 | 8.09 | ||||

| Popular Will | 471,677 | 3.17 | ||||

| Progressive Advance | 256,022 | 1.72 | ||||

| Venezuela Vision Unity | 131,619 | 0.88 | ||||

| National Integration Movement | 110,839 | 0.75 | ||||

| United for Venezuela | 64,380 | 0.43 | ||||

| Progressive Movement of Venezuela | 51,976 | 0.35 | ||||

| Ecological Movement of Venezuela | 40,523 | 0.27 | ||||

| Democracy Renewal Unity | 36,126 | 0.24 | ||||

| Vamos Adelante | 34,938 | 0.23 | ||||

| Force of Change | 33,374 | 0.22 | ||||

| People's Vanguard | 31,279 | 0.21 | ||||

| Liberal Force | 22,965 | 0.15 | ||||

| Unidad Nosotros Organizados Elegimos | 20,444 | 0.14 | ||||

| Procommunity | 18,748 | 0.13 | ||||

| Movement for a Responsible, Sustainable and Entrepreneurial Venezuela | 18,644 | 0.13 | ||||

| Other votes | 470 | 0.00 | ||||

| Total | 6,591,304 | 44.32 | ||||

| Reina Sequera | UD–PL | Democratic Union | 65,997 | 0.44 | ||

| Labour Power | 4,553 | 0.03 | ||||

| Other votes | 17 | 0.00 | ||||

| Total | 70,567 | 0.47 | ||||

| Luis Reyes Castillo | Authentic Renewal Organization | 8,214 | 0.06 | |||

| María Bolívar | United Democratic Party for Peace | 7,378 | 0.05 | |||

| Orlando Chirino | Party for Socialism and Liberty | 4,144 | 0.03 | |||

| Total | 14,872,739 | 100.00 | ||||

| Valid votes | 14,872,739 | 98.10 | ||||

| Invalid/blank votes | 287,550 | 1.90 | ||||

| Total votes | 15,160,289 | 100.00 | ||||

| Registered voters/turnout | 18,903,937 | 80.20 | ||||

| Source: CNE | ||||||

By state[edit]

| States/districts won by Hugo Chávez |

| States/districts won by Henrique Capriles |

| Hugo Chávez PSUV |

Henrique Capriles MUD |

Others Various |

Margin | State total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | # |

| Capital District | 695,162 | 54.85 | 564,312 | 44.52 | 7,813 | 0.62 | 130,850 | 10.33 | 1,267,287 |

| Amazonas | 39,056 | 53.61 | 33,107 | 45.46 | 677 | 0.93 | 5,949 | 8.17 | 72,840 |

| Anzoátegui | 409,499 | 51.58 | 378,345 | 47.65 | 6,050 | 0.76 | 31,154 | 3.92 | 793,894 |

| Apure | 155,988 | 66.09 | 78,358 | 33.20 | 1,652 | 0.70 | 77,630 | 32.89 | 235,998 |

| Aragua | 552,878 | 58.61 | 384,592 | 40.77 | 5,708 | 0.61 | 168,286 | 17.84 | 943,178 |

| Barinas | 243,618 | 59.23 | 165,135 | 40.15 | 2,526 | 0.61 | 78,483 | 19.08 | 411,279 |

| Bolívar | 387,462 | 53.73 | 327,776 | 45.46 | 5,766 | 0.80 | 59,686 | 8.28 | 721,004 |

| Carabobo | 652,022 | 54.49 | 537,077 | 44.88 | 7,419 | 0.62 | 114,945 | 9.61 | 1,196,518 |

| Cojedes | 116,578 | 65.31 | 60,584 | 33.94 | 1,323 | 0.74 | 55,994 | 31.37 | 178,485 |

| Delta Amacuro | 54,963 | 66.84 | 26,506 | 32.23 | 758 | 0.92 | 28,457 | 34.61 | 82,227 |

| Falcón | 296,902 | 59.87 | 195,619 | 39.45 | 3,337 | 0.67 | 101,283 | 20.43 | 495,858 |

| Guárico | 249,038 | 64.31 | 135,451 | 34.97 | 2,740 | 0.71 | 113,587 | 29.33 | 387,229 |

| Lara | 499,525 | 51.45 | 463,615 | 47.75 | 7,637 | 0.79 | 35,910 | 3.70 | 970,777 |

| Mérida | 227,276 | 48.45 | 239,653 | 51.09 | 2,126 | 0.45 | −12,377 | −2.64 | 469,055 |

| Miranda | 771,053 | 49.96 | 764,180 | 49.52 | 7,912 | 0.51 | 6,873 | 0.44 | 1,543,145 |

| Monagas | 272,480 | 58.35 | 191,178 | 40.94 | 3,238 | 0.69 | 81,302 | 17.41 | 466,896 |

| Nueva Esparta | 132,452 | 51.02 | 125,792 | 48.45 | 1,349 | 0.52 | 6,660 | 2.57 | 259,593 |

| Portuguesa | 327,960 | 70.89 | 131,100 | 28.33 | 3,539 | 0.77 | 196,860 | 42.56 | 462,599 |

| Sucre | 280,933 | 60.23 | 182,898 | 39.21 | 2,565 | 0.55 | 98,035 | 21.02 | 466,396 |

| Táchira | 274,573 | 43.29 | 356,713 | 56.23 | 2,957 | 0.47 | −82,140 | −12.95 | 634,243 |

| Trujillo | 252,051 | 64.10 | 139,195 | 35.40 | 1,940 | 0.49 | 112,856 | 28.70 | 393,186 |

| Vargas | 127,246 | 61.47 | 78,382 | 37.86 | 1,374 | 0.66 | 48,864 | 23.61 | 207,002 |

| Yaracuy | 194,412 | 59.99 | 127,442 | 39.32 | 2,179 | 0.67 | 66,970 | 20.67 | 324,033 |

| Zulia | 971,889 | 53.34 | 843,032 | 46.27 | 7,038 | 0.39 | 128,857 | 7.07 | 1,821,959 |

| Foreign | 5,716 | 8.45 | 61,229 | 90.54 | 679 | 1.00 | −55,513 | −82.09 | 67,624 |

| Inhospitable | 400 | 92.16 | 33 | 7.60 | 1 | 0.23 | 367 | 68.19 | 434 |

| Totals: | 8,191,132 | 55.07 | 6,591,304 | 44.31 | 90,303 | 0.61 | 1,599,828 | 10.76 | 14,872,739 |

| Source: CNE | |||||||||

Close states[edit]

Red font color denotes states won by President Chávez; blue denotes those won by Governor Capriles.

States where the margin of victory was under 5%:

- Miranda 0.45%

- Nueva Esparta 2.57%

- Mérida 2.64%

- Lara 3.70%

- Anzoátegui 3.92%

States where margin of victory was more than 5% but less than 10%:

- Zulia 7.07%

- Amazonas 8.17%

- Bolívar 8.28%

- Carabobo 9.61%

Reactions[edit]

International[edit]

Argentina – Argentina's President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner released a message on Twitter saying: "Hugo, today I wish to tell you that you have plowed the earth, you have sown it, you have watered it, and today you have picked up the harvest."[100] She called the election a victory for all "South Americans and the Caribbeans."

Argentina – Argentina's President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner released a message on Twitter saying: "Hugo, today I wish to tell you that you have plowed the earth, you have sown it, you have watered it, and today you have picked up the harvest."[100] She called the election a victory for all "South Americans and the Caribbeans." Bolivia – Bolivian President Evo Morales called the election result a victory for all "the nations of Latin America that fight for their sovereign dignity."[100]

Bolivia – Bolivian President Evo Morales called the election result a victory for all "the nations of Latin America that fight for their sovereign dignity."[100] Brazil – Brazilian Foreign Minister Antonio Patriota congratulated Chavez on his victory and praised Capriles for his swift recognition of defeat.

Brazil – Brazilian Foreign Minister Antonio Patriota congratulated Chavez on his victory and praised Capriles for his swift recognition of defeat. Cuba – Cuban President Raúl Castro released a message from the country's embassy in Mexico City stating "Your decisive victory assures the continuation of the struggle for the genuine integration of Our America"[100] and that the election "shows the strength of the Bolivarian Revolution and its unquestionable grassroots support."

Cuba – Cuban President Raúl Castro released a message from the country's embassy in Mexico City stating "Your decisive victory assures the continuation of the struggle for the genuine integration of Our America"[100] and that the election "shows the strength of the Bolivarian Revolution and its unquestionable grassroots support." Ecuador – Ecuadorean President Rafael Correa posted a message on Twitter congratulating Chavez and declaring: "All of Latin American is with you and with our beloved Venezuela. ... Next battle: Ecuador!"[100]

Ecuador – Ecuadorean President Rafael Correa posted a message on Twitter congratulating Chavez and declaring: "All of Latin American is with you and with our beloved Venezuela. ... Next battle: Ecuador!"[100] Iran – Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad issued a message congratulating Chavez on his re-election. In the message he also emphasized the need for Iran and Venezuela to increase cooperation.[101]

Iran – Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad issued a message congratulating Chavez on his re-election. In the message he also emphasized the need for Iran and Venezuela to increase cooperation.[101] Nicaragua – Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega congratulated Chavez, calling him "an indisputable leader that will continue leading the Latin American Revolution."

Nicaragua – Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega congratulated Chavez, calling him "an indisputable leader that will continue leading the Latin American Revolution." Russia – According to the presidential press service, Russian President Vladimir Putin congratulated Hugo Chávez in a telephone conversation.[citation needed]

Russia – According to the presidential press service, Russian President Vladimir Putin congratulated Hugo Chávez in a telephone conversation.[citation needed] United States – White House Press Secretary Jay Carney congratulated the Venezuelan people on the high voter turnout and "peaceful elections".[102]

United States – White House Press Secretary Jay Carney congratulated the Venezuelan people on the high voter turnout and "peaceful elections".[102] Uruguay – Uruguayan President Jose Mujica used the election the victory to urge Latin American nations for more cooperation and put aside differences.

Uruguay – Uruguayan President Jose Mujica used the election the victory to urge Latin American nations for more cooperation and put aside differences.

References[edit]

- ^ "Venezuela sets 2012 presidential election date". BBC. 13 September 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ^ El Mundo: Estos son los ocho candidatos para las presidenciales del 7 de octubre Archived 17 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Laclase.info (15 June 2012).

- ^ "Venezuela.- Capriles desea "larga vida" a Chávez en medio de la polémica por la salud del presidente". Expansion.com.

- ^ "Divulgación Elecciones Presidenciales - 07 de Octubre de 2012". 4.cne.gob.ve. Archived from the original on 22 July 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ "Chávez Wins a Third Term in Venezuela Amid Historically High Turnout". NYT. 7 October 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ^ "Capriles a Chávez: Espero que lea con grandeza la expresión del pueblo". El Universal. 7 October 2012. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ^ "Venezuela's presidential election, 2012". Smartmatic.com.

- ^ Consejo Nacional Electoral Manual Operativo para Miembros, Secretaria o Secretario de Mesa Electoral Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 28 November 2006 (in Spanish)

- ^ Chinea, Eyanir. (10 June 2012) "Capriles rallies Venezuelans to challenge Chavez". Reuters.

- ^ "Chavez foe leads massive march in Venezuela". Fox News.

- ^ "CARACAS: Venezuela opposition floods streets in support of presidential candidate" Archived 7 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Miami Herald.

- ^ "Capriles Radonski quiere ser 'el Presidente de los rojos'" Archived 15 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine. El Tiempo (1 June 1999).

- ^ "Hugo Chávez se postulará para las Presidenciales del 2012". Noticias 24 (in Spanish). 23 November 2010. Archived from the original on 30 January 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ^ "Chavez to run in 2012 poll, says Venezuela minister". BBC. 18 July 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ a b de la Rosa, Alicia (12 February 2012). "Henrique Capriles wins opposition primaries in Venezuela". El Universal. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ "De oposicion a unidad". Tal Cual (in Spanish). 13 February 2012. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "A total of 3,040,449 votes were cast in opposition primary election". El Universal. 13 February 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Gupta, Girish (10 February 2012). "Meet Henrique Capriles, Chavez's first real challenger". Global Post. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ Rueda, Jorge (16 September 2011). "Rights court sides with Chavez opponent". The Guardian. Associated Press. Retrieved 16 September 2011. Also available from Rights court sides chavez opponent, Yahoo! news

- ^ "Venezuela's López pulls out of presidential race". Buenos Aires Herald. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ "Chavez opponents in drive for unity". UK Press Association. 24 January 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2012.[dead link]

- ^ "Otro candidato menos: Antonio Ledezma anuncia que se retira de la contienda electoral". Informe21.com (in Spanish). 31 October 2011. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Romo, Rafael (14 February 2012). "Political crisis erupts in Venezuela after primary elections". CNN. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ a b c "Venezuela opposition: Row erupts over voter list". BBC News. 14 February 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g Vyas, Kejal & Jose de Cordoba (15 February 2012). "Chávez rival hit by state attacks". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ Guillen, Erika (14 February 2012). "Muere joven durante decomiso de cuadernos electorales en Aragua". El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ a b c d Toothaker, Christopher & Ian James (20 February 2012). "Venezuelan challenger aims to oust Chavez". The Washington Times. Associated Press. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ "Factbox: What does Henrique Capriles want for Venezuela?". Reuters. 1 April 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- ^ "Venezuela's presidential campaign: And then there were five", The Economist, 26 January 2012

- ^ de Córdoba, José (11 February 2012), "Venezuelans Aim to Challenge Chávez", The Wall Street Journal

- ^ Sullivan, Mark P.; Olhero, Nelson (11 January 2008), "Venezuela: Political Conditions and U.S. Policy" (PDF), CRS Report for Congress, p. 12

- ^ a b c d Cawthorne, Andrew (1 April 2012). "Insight: The man who would beat Hugo Chavez". Reuters. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- ^ Andrew Cawthorne, Reuters, 6 November 2011, Chavez says foes would harm slums, see off Cubans

- ^ Andrew Cawthorne, Reuters, 14 February 2012, Chavez still feels the love in Venezuela slums

- ^ (in Spanish) Últimas Noticias, 6 September 2012, Aseguran que Capriles R. tiene un plan distinto al que dice Archived 1 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (in Spanish) Últimas Noticias, 6 September 2012, UNT: Ojeda "se puso al margen" de este partido Archived 1 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (in Spanish) El Tiempo, 7 September 2012, UNT suspendió a William Ojeda tras criticar supuesto "paquete" de la MUD Archived 1 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (in Spanish) noticias24.com, 7 September 2012, José Guerra: "Capriles no tiene ninguna agenda oculta, está jugando con las cartas sobre la mesa" Archived 1 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (in Spanish) Últimas Noticias, 11 September 2012, Denuncian que De Lima pagó a partidos para retirar apoyo a HCR Archived 1 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (in Spanish) Últimas Noticias, 12 September 2012, De Lima niega haber ofrecido dinero a partidos minoritarios Archived 1 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Rafael Poleo: Las encuestas muestran a un Capriles flojo con una estrategia equivocada". NoticieroDigital (in Spanish). 21 May 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

ignora que en Venezuela el voto es emocional (…) y que la gente vota por la esperanza". ... "el chavismo llegó al corazón del pueblo que AD y Copei, sifrinizados, habían dejado vacío" ... "Por este camino puedo desde ya decirles los resultados.

- ^ a b Reuters, 18 June 2012, Venezuela's Chavez rejects poll debate, irking rival

- ^ López Maya, Margarita (2016). El ocaso del chavismo: Venezuela 2005-2015. pp. 349–351. ISBN 9788417014254.

- ^ a b c d e f Brice, Arthur (1 May 2012). "Chavez health problems plunge Venezuela's future into doubt". CNN. Archived from the original on 24 June 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2012. Article extends to 11 pages.

- ^ a b "Hugo Chavez's cross: Venezuelan leader turns to Christianity during struggle with cancer". The Washington Post. Associated Press. 7 May 2012. Archived from the original on 8 May 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- ^ a b "Hugo Chavez ahead in Venezuela presidential race even as he fights cancer, prays for life". The Washington Post. Associated Press. 12 April 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2012.[dead link]

- ^ a b c Cawthorne, Andrew (4 May 2012). "Talk of Chavez cancer downturn rattles Venezuela". Chicago Tribune. Reuters. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- ^ a b Ellsworth, Brian & Andrew Cawthorne (7 May 2012). "Chavez breaks silence, says governing Venezuela". Chicago Tribune. Reuters. Retrieved 8 May 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Reuters, 22 May 2012, UPDATE 1-Venezuela's Chavez reappears, leads cabinet meeting

- ^ a b Toothaker, Christopher (17 February 2012). "Henrique Capriles Radonski: Hugo Chavez foe a target of anti-Semitism". HuffPost. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ a b Devereux, Charlie (20 February 2012). "Chavez media say rival Capriles backs plots ranging from Nazis to Zionists". Bloomberg. Retrieved 21 February 2012. Also available from sfgate.com

- ^ "Anti-Semitic article appears in Venezuela". Anti-Defamation League. 17 February 2012. Archived from the original on 12 May 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2012. Includes English translation of Venezuelan National Radio article.

- ^ a b "Chavez allies attack new opponent Capriles as Jewish, gay". MSNBC. 15 February 2012. Archived from the original on 2 May 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- ^ "Chávez requested to stop anti-Semitic attacks against Capriles". El Universal. 17 February 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ EFE, Fox News, 14 July 2012, Capriles says message to Venezuela military went over "very well"

- ^ (in Spanish) Globovision, 13 July 2012, Chávez: Mensaje de Capriles a la FANB es el "colmo de la hipocresía" Archived 24 January 2013 at archive.today

- ^ a b c d Brian Ellsworth and Eyanir Chinea, Reuters, 6 June 2012, Venezuela 'poll wars' rage as presidential race heats up

- ^ (in Spanish) El Universal, 8 June 2012, CNE establece el registro obligatorio de encuestadoras

- ^ (in Spanish) CNE, Listado de Encuestadoras Registradas ante el CNE. Archived 25 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hinterlaces. Hinterlaces.

- ^ "Hinterlaces: 51% think that Venezuela is going the wrong way". El Universal. 30 January 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ IVAD Archived 2 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine. IVAD.

- ^ "Encuesta IVAD: Gestión del presidente Chávez con 74,6% de apoyo" (in Spanish). noticiaaldia.com. 5 February 2012. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ Rosenberg, Mica & Diego Ore (11 March 2012). "Down but not out, sick Chavez seeks re-election in Venezuela". Reuters. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ^ "Jefe de Estado lidera encuestas con intención de voto en 56,5 por ciento" (in Spanish). RNV. 17 March 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ^ "Consultores 21 S.A. |".

- ^ Goodman, Joshua (22 March 2012). "Chavez Turns to Generals to Defend Revolution Amid Illness". Bloomberg. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ Datanalisis. Datanalisis.

- ^ Rodriguez, Corina (22 March 2012). "Venezuela's Capriles May Close Gap on Chavez in Polls, Leon Says". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ "Encuesta: 49,3% votaría por Chávez y 45,1% por Capriles Radonski" (in Spanish). eltiempo.com.ve. 9 April 2012.

- ^ "The Pros And Cons of Anabolic Steroid Usage". Gisxxi.org. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ "Candidatos y encuestas, realidad y especulaciones (Jesse Chacón- GISXXI)" (in Spanish). GIS XXI. 13 May 2012. Archived from the original on 17 May 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ^ "Varianzas da 50,5% de intención de voto a Chávez y 45,7% a Capriles" (in Spanish). El Universal. 29 May 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ^ "Venezuela poll shows tight race for Chavez". Chicago Tribune. 28 June 2012. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- ^ "Una nueva encuesta da un empate técnico entre Chávez y Capriles" (in Spanish). europapress.es. 3 July 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ^ "Chávez pone tierra de por medio en las encuestas". El Correo (in Spanish). 9 July 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ "Varianzas: Chávez aventaja a Capriles en 4 puntos a 3 meses del 7-O" (in Spanish). noticias24.com. 7 July 2012. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ "Datanálisis gives Chávez 15.3 points ahead of Capriles Radonski". El Universal. 16 July 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ "Hinterlaces: Chávez baja 5 puntos en intención de voto, Capriles 4, indecisos crecen en 300% a 20". Noticierodigital.com%. 18 July 2012.

- ^ "GIS XXI: 56% de los venezolanos votaría a favor del candidato Hugo Chávez | MinCI". Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ "Poll shows Chavez with slim lead ahead of Venezuela election". Latino.foxnews.com.

- ^ "Venezuela poll shows Chavez has slim lead". The Australian. 19 August 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- ^ Daniel Cancel (20 August 2012). "Chavez Lead Narrows in Latest Datanalisis Poll in Venezuela". Bloomberg. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- ^ "Capriles leads in new Venezuela poll". iol.co.za. 24 August 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ "Rival tops Hugo Chavez in Venezuela poll". San Francisco Chronicle. 19 September 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ^ "Opositor reduce brecha con Chávez para elección Venezuela:sondeo" (in Spanish). Reuters. 24 September 2012. Archived from the original on 25 March 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ "Lea completo el más reciente estudio de la encuestadora Hinterlaces, presentado este miércoles" (in Spanish). noticias24.com. 26 September 2012. Archived from the original on 30 September 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ a b "October election already fuelling threats and violence against media". Reporters Without Borders. 24 March 2012. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ a b c "Globovisión journalists attacked in Venezuela". Committee to Protect Journalists. 6 March 2012. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

- ^ a b Reporters without Borders, 21 March 2012, October election already fuelling threats and violence against media Archived 8 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (in Spanish) El Nacional, 20 March 2012, AN debatirá supuesta agresión del diputado Mardo hacia periodista Ana Francis Colina Archived 21 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (in Spanish) Noticias24, 20 March 2012, AN aprueba propuesta de solicitar a la FGR una investigación "exhaustiva" sobre el caso de Richard Mardo Archived 22 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (in Spanish) Noticias24, 19 May 2012, La Felap rechaza agresiones contra comunicadores de medios públicos Archived 22 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Toothaker, Christopher (12 May 2012). "Chavez returns home after cancer treatment in Cuba". AP. Retrieved 23 May 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Cabello: El único que garantiza la paz en Venezuela se llama Hugo Chávez". El Universal (in Spanish). 10 March 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ a b Hernandez F.; Alejandra M. (20 March 2012). "Chávez reports on plot to kill opposition rival Capriles Radonski". El Universal. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ Wallis, Daniel (21 March 2012). "Venezuela's Capriles to campaign despite talk of plot". Reuters. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ "Chavez threatens banks, firms backing opposition". Yahoo News. Agence France-Presse. 30 March 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2012. [dead link]

- ^ "Celebrando con odio". La Nacion (in Spanish). talcualdigital.com. 13 April 2012. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Latin American governments congratulate Chavez win in Venezuela". 8 October 2012.

- ^ Tehran Times Iranian president congratulates his Venezuelan counterpart Archived 16 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Feller, Ben (8 October 2012). "White House salutes Venezuelan people on election". Associated Press via The Huffington Post. Retrieved 9 October 2012.